Parental Attitudes to Risky Play and Children’s Independent Mobility: Public Health Implications for Children in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk-Averse Society

1.2. Child Safety Concerns

1.3. International Support for Play

1.4. Children’s Independent Mobility

1.5. Societal Factors Influencing Opportunities for Play

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

2.2. Approval

2.3. Consent Process

2.4. Development and Testing

2.5. Recruitment Process and Participants

2.6. Survey Administration

2.7. Materials

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Limitations

3. Results

Rain as a Potential Barrier to Risky Play

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Participant Information Leaflet

- Why is this study being done?

- Why have I been invited to take part?

- Do I have to take part? Can I withdraw?

- What happens if I change my mind?

- How will the study be carried out and what will happen if I decide to take part?

- Data protection

- Are there any benefits or risks to taking part in this research?

- Will I be told the outcome of the study?

- Has this study been approved by a research ethics committee?

- Who is organising and funding this study?

- Is there any payment for taking part?

- Who should I contact for information or complaints?

Appendix B. State of Play Survey PARK Project

- Climb trees at home or in their local park/recreation areas

- Climb trees at their early childhood centre/school

- Engage in rough-and-tumble games (e.g., wrestling) at home

- Engage in rough-and-tumble games (e.g., wrestling) at their early childhood centre/school?

- Use adult tools (e.g., hammers, saws, drills) at home

- Use adult tools (e.g., hammers, saws, drills) at early childhood centre/school

- Roam their neighbourhood with friends but unsupervised by adults?

- Roam their neighbourhood alone?

- Roam their early childhood centre/school grounds during recess and lunch breaks unsupervised by teachers?

- Use loose parts (e.g., sticks, tires, timber) during outdoor play at home?

- Use loose parts (e.g., sticks, tires, timber, tarpaulins) during outdoor play at their early childhood centre/school?

- Engage in ‘messy’ play (e.g., mud, dirt, sand, water, paint) at home?

- Engage in ‘messy’ play (e.g., mud, dirt, sand, water, paint) at at their early childhood centre/school?

- Ride non-motorised vehicles (e.g., bikes, scooters, go-karts) in their neighbourhood while supervised by adults?

- Ride non-motorised vehicles (e.g., bikes, scooters, go-karts) in their neighbourhood with friends but unsupervised by adults?

- Ride non-motorised vehicles (e.g., bikes, scooters, go-karts) in their neighbourhood alone?

- Play on playground equipment (monkey bars, ladders, slides)?

- Play on trampolines?

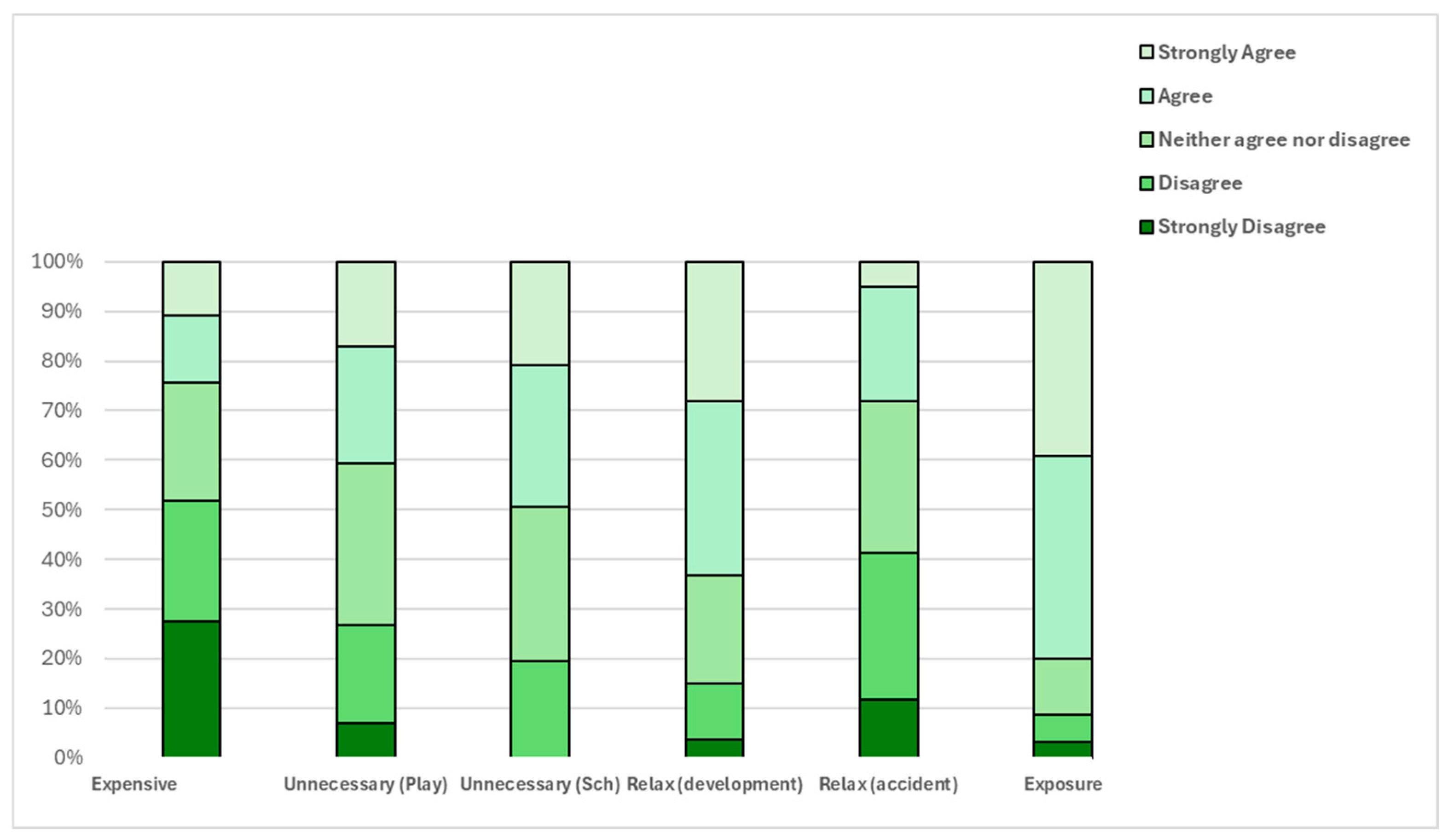

- Finding ways to get children active is expensive these days.

- There are too many unnecessary safety rules applied to children’s play in Ireland today.

- There are too many unnecessary safety rules in Irish schools today.

- Relaxing the safety rules and introducing traditional risky play practices and equipment in schools would enhance children’s development.

- Relaxing the safety rules and introducing traditional risky play practices and equipment in schools would result in an increase in serious accidents and injuries.

- Children require regular exposure to actual risk in order to develop risk management skills.

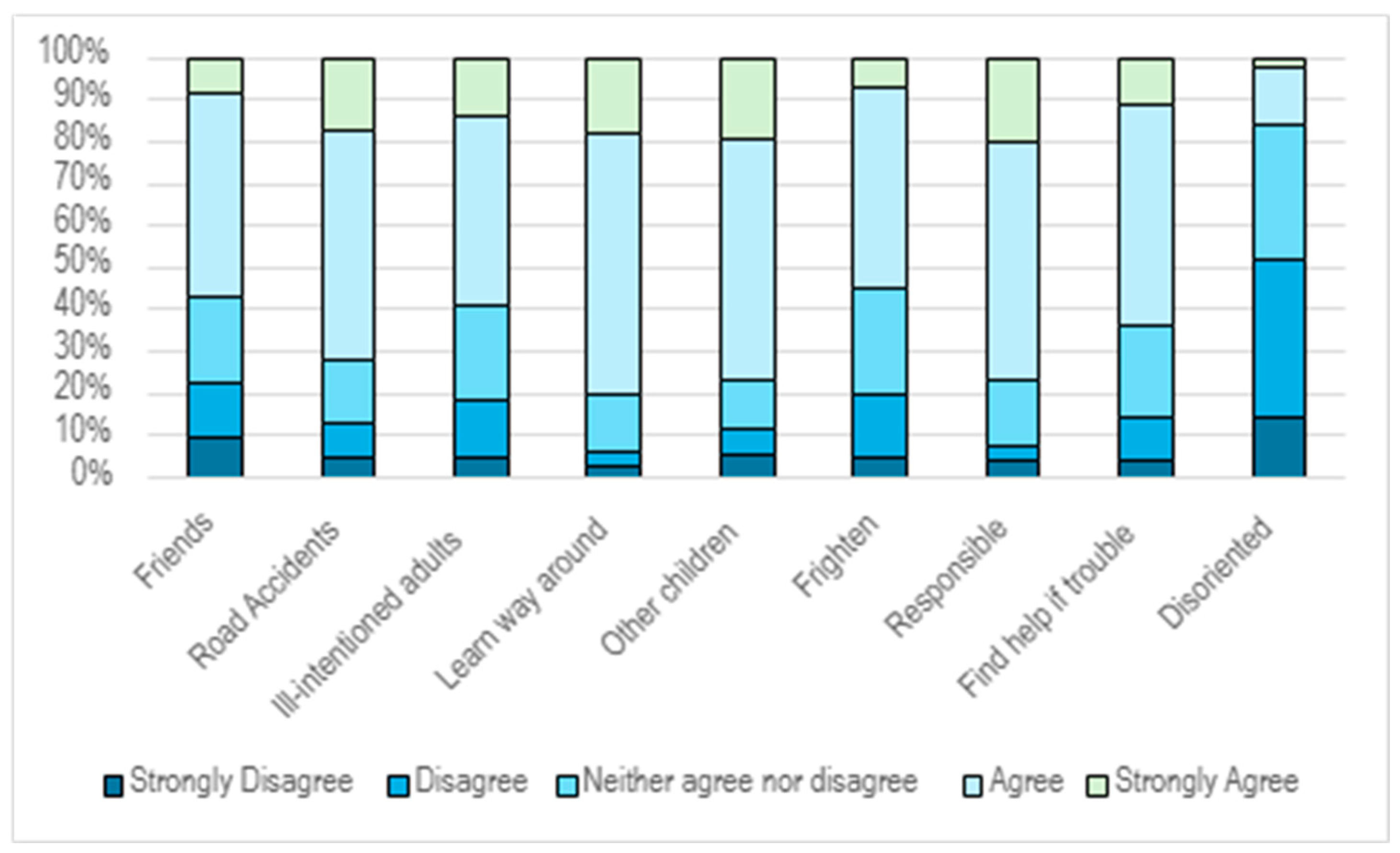

- Make new friends.

- Be exposed to the risk of road accidents.

- Encounter ill-intentioned adults.

- Learn his or her way around.

- Meet and/or play with other children.

- See things that may frighten him or her.

- Become more responsible.

- Find someone willing to help them in case of trouble.

- Feel disoriented when among people.

- Jump down from a height of 3–4 m?

- Allow the child play chase with other children?

- Trust the child to play by themselves without constant supervision?

- Trust the child to go head first down a slippery slide?

- Allow the child to continue playing if they get a few scrapes during play?

- Let the child have lots of challenges when they play at home?

- Let the child use a hammer and a nail unsupervised?

- Climb up a tree within your reach?

- Walk barefoot across a floor after broken glass had been swept up?

- Walk on slippery rocks close to water?

- Let the child play fight other children with sticks?

- Encourage the child to try new things that involve some risk?

- Engage in rough and tumble play?

- Play near the edge of steep cliffs?

- Allow the child play in undeveloped rural areas out of sight?

- Let the child experience minor mishaps if what they are doing is lots of fun?

- Let the child run close to an open fire?

- Swim in the sea close to the shore while you were watching from the beach?

- Allow the child to continue playing if there potential they may break a bone?

- Allow the child play in the rear garden unsupervised?

- Allow the child play-fight testing who is the strongest?

- Allow the child to climb a rock wall that goes straight down to the water?

- Would you wait to see if the child can manage challenges on their own before getting involved?

- Let the child climb as high as they want to in trees?

- Allow the child to ride a bicycle downhill at speed?

- Would you trust the child to play safely?

- Allow the child to use a sharp knife?

- Allow the child to play in a back garden supervised?

- Allow the child to balance on a fallen tree more than 2 m above the ground?

- Encourage the child to take some risks if it means having fun during play?

- Allow the child to climb up a tree beyond your reach?

- Use adult tools (saws, hammers, drills)?

- Climb trees?

- Engage in rough and tumble games?

- Roam their neighbourhood with friends but unsupervised?

- Roam their neighbourhood alone?

- Use loose parts (sticks, tyres, timber) when playing outdoors?

- Engage in messy play (dirt, mud, sand, water, paint)?

- Ride non-motorised vehicles (scooter, bike, balance bike, go-kart) in the neighbourhood with friends unsupervised by adults?

- Ride non-motorised vehicles (scooter, bike, balance bike, go-kart) in the neighbourhood alone?

- It would be too cold for my child

- My child may get sick

- My child would get too messy

- My child may slip or have an accident.

- I don’t like being outside in the rain.

- My child doesn’t like being outside in the rain.

- Not having suitable weatherproof clothing for my child

- I do not have suitable weatherproof clothing.

- Other

- I am concerned about the things I cannot control that can physically injure my child

- Fewer injuries happen to children when parents plan ways to prevent them

- I am concerned about the potential hazards in my home.

- Children should play in the places where there is low risk of injury

- Good supervision of my child means knowing what my child is doing at all times.

- Letting my child engage in physical activities without supervision greatly increases their chance of injury

- It is important for my child to engage in physically challenging experiences.

- I like to let my child find his or her physical limits

- I value opportunities for my child to explore new environments

- The benefits of physical activity for my child outweigh the risk of experiencing minor injuries

- I prefer to teach my child how to manage risky situations rather than avoid them.

- Participating in challenging and potentially risky physical activities will help my child develop self-confidence

- It feels as if I am always driving my child to an organised activity or sport.

- The number of organised activities or sports my child participates in is a source of stress for the family.

Appendix C

| Category | Risk Involved | Sub-Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Great Heights | Danger of falling | Climbing, jumping, Balancing on high objects Hanging/swinging at great heights |

| Great Speed | Uncontrolled Speed and pace that could result in collision with something or someone | Swinging, sliding or sledging at high speed. Cycling, skating or skiing at high speed. Running uncontrollably |

| Dangerous tools | Can lead to injuries and wounds | Cutting tools, and strangling tools. |

| Dangerous elements | Where children can fall into or from something | Cliffs, deep water, fire pits |

| Rough and tumble | Where children can harm each other | Wrestling, fencing with sticks, play fighting. |

| Disappear/get lost | Where children can disappear from adult supervision and get lost alone. | Exploring alone, playing alone in unfamiliar environments. |

References

- Whitebread, D. Free play and children’s mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2012, 1, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty Ser. 1989, 1577, 3. [Google Scholar]

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). General Comment No. 17 (2013) on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural life, And the Arts (Art. 31), 17 April 2013. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/general/crc/2013/en/96090 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gray, P. Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play will Make our Children Happier, More self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life; Basic Books/Hachette Book Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. The Benefits of Children’s Engagement with Nature: A Systematic Literature Review. Child. Youth Environ. 2014, 24, 10–34. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublication?journalCode=chilyoutenvi (accessed on 11 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kennaire, L.E.O. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The antiphobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, H.F.; Fitzgibbon, L.; Watson, B.E.; Nesbit, R.J. Children’s play and independent mobility in 2020: Results from the British Children’s Play Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2021, 18, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.J.; Traunter, J. Muddy knees and muddy needs: Parents perceptions of outdoor learning. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, G.; Dias, G. The importance of outdoor play for young children’s healthy development. Porto Biomed. J. 2017, 2, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuling, L.; Õun, T.; Ugaste, A. Teachers’ opinions on utilizing outdoor learning in the preschools of Estonia. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2019, 19, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J. Early Childhood Educators’ Preferences and Perceptions Regarding Outdoor Settings as Learning Environments. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2014, 2, 97–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P.; Woolley, H. Optimizing Urban Children’s Outdoor Play Spaces: Affordances, Supervision, and Design Dynamics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Lin, Y.; Han, C.; Janssen, I.; Schuurman, N.; Boyes, R.; Swanlund, D.; Mâsse, L.C. A qualitative investigation of unsupervised outdoor activities for 10-to 13-year-old children: “I like adventuring but I don’t like adventuring without being careful”. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, R.J.; Bagnall, C.L.; Harvey, K.; Dodd, H.F. Perceived barriers and facilitators of adventurous play in schools: A qualitative systematic review. Children 2021, 8, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrable, A.; Booth, D. Increasing nature connection in children: A mini review of interventions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J. Exploring Young Children’s and Parents’ Preferences for Outdoor Play Settings and Affinity toward Nature. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2018, 5, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, E.J.; Williams, P.H. Risk-tasking and assessment in toddlers during nature play: The role of family and play context. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2020, 20, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Cordovil, R.; Hagen, T.L.; Lopes, F. Barriers for Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Institutions: Perception of Risk in Children’s Play among European Parents and ECEC Practitioners. Child Care Pract. 2019, 26, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanscom, A.J. Balanced and Barefoot: How Unrestricted Outdoor Play Makes for Strong, Confident, and Capable Children; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, L.; Laird, S.G. “She’s only two”: Parents and educators as gatekeepers of children’s opportunities for nature-based risky play. In Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1075–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, H.F.; Lester, K.J. Adventurous play as a mechanism for reducing risk for childhood anxiety: A conceptual model. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, L. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, H.E.; Griffin, E. Decreasing experiences of home range, outdoor spaces, activities and companions: Changes across three generations in Sheffield in north England. Child. Geogr. 2015, 13, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H. Mothers beliefs about risk and risk-taking in children’s outdoor play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 15, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, A.; Watson, B.; Shaw, B.; Hillman, M. A comparison study of children’s independent mobility in England and Australia. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, T.; Spencer-Cavaliere, N. Times have changed: Parent perspectives on children’s free play and sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 32, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, L.; Lin, Y.; Ishakawa, T.; Masse, L.C.; Brussoni, M. Comparison of risk engagement and protection survey (REPS) among mothers and fathers of children aged 6–12 years. Inj. Prev. 2019, 25, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelleyman, C.; McPhee, J.; Brussoni, M.; Bundy, A.; Duncan, S. A cross-sectional description of parental perceptions and practices related to risky play and independent mobility in children: The New Zealand State of Play Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 2019, 16, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, F.; Henwood, K.; Coltart, C. Meeting the challenges of intensive parenting culture: Gender, risk management and the moral parent. Sociology 2012, 46, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R.A.; Stone, E.R.; Buchanan, C.M. A social values analysis of parental decision making. J. Psychol. 2014, 148, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Play or learn: European-American and Chinese kindergartners’ perceptions about the conflict. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 86, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, E.; Beno, S. Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play: Navigating the balance with injury prevention. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 29, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Wyver, S. Outdoor play: Does avoiding the risks reduce the benefits? Australas. J. Early Child. 2008, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rance, T.; Ramchandani, P.; Hesketh, K.R. Risky play: Our children need more. Arch. Dis. Child. 2025. ahead of print. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39332839/ (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, S.; Russell, W. Play for a Change: Play, Policy, and Practice: A Review of Contemporary Perspectives; National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Tamminen, K.A.; Clark, A.M.; Slater, L.; Spence, J.C.; Holt, N.L. A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children’s independent active free play. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furedi, F. Culture of Fear Revisited: Risk Taking and the Morality of Low Expectation, 4th ed.; Continuum: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, P. The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Am. J. Play 2011, 3, 443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. Discourses of childhood safety: What do children say? Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 22, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.J. Play and Risk-In Search of New Ground. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Ball-10/publication/228889933_Play_and_Risk_in_search_of_new_ground/links/54d0ffa70cf25ba0f040966a/Play-and-Risk-in-search-of-new-ground.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Miles, R. Neighbourhood Disorder, Perceived Safety and Readiness to Encourage Use of Local Playgrounds. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G.; McKendrick, J. Children’s Outdoor Play: Exploring Parental Concerns about Children’s Safety and the Changing Nature of Childhood. Geoforum 1997, 28, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, H.; Christie, S. Mommy, can I play outside? How urban design influences parental attitudes on play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, K.; Van Aalst, I.; Meijer, M. Creating environments for risky play: Understanding the interplay between parents, play professionals and policymakers. Child. Soc. 2024, 38, 2071–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.A.; Graham, A. Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy–practice nexus. Aust. Educ. Res. 2017, 44, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Bagley, S.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J. Where do children usually play? A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions of influences on children’s active free-play. Health Place 2006, 12, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.; McCormack, G.R.; Timperio, A.; Middleton, N.; Beesley, B.; Trapp, G. How far do children travel from their homes? Exploring children’s activity spaces in their neighborhood. Health Place 2012, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyttä, M.; Hirvonen, J.; Rudner, J.; Pirjola, I.; Laatikainen, T. The last free-range children? Children’s independent mobility in Finland in the 1990s and 2010s. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Faulkner, G.E.; Buliung, R.N.; Stone, M.R. Do parental perceptions of the neighbourhood environment influence children’s independent mobility? Evidence from Toronto, Canada. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 3401–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Gray, C.; Babcock, S.; Barnes, J.; Bradstreet, C.C.; Carr, D.; Chabot, G.; Choquette, L.; Chorney, D.; Collyer, C.; et al. Position statement on active outdoor play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6475–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skenazy, L. Free-Range Kids: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts with Worry); Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.; Villanueva, K.; Wood, L.; Christian, H.; Giles-Corti, B. The impact of parents’ fear of strangers and perceptions of informal social control on children’s independent mobility. Health Place 2014, 26, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Mårtensson, F.; Jansson, M.; Sternudd, C. Urban space for children on the move. In Transport and Children’s Wellbeing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B.; Watson, B.; Frauendienst, B.; Redecker, A.; Jones, T.; Hillman, M. Children’s Independent Mobility: A Comparative Study in England and Germany (1971–2010); Policy Studies Institute: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.; Adamakis, M.; O’Brien, W.; Martins, J. A Scoping Review of Children and Adolescents’ Active Travel in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.; Witten, K.; Kearns, R.A.; Mavoa, S.; Badland, H.M.; Carroll, P.; Drumheller, C.; Tavae, N.; Asiasiga, L.; Jelley, S.; et al. Kids in the city study: Research design and methodology. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, C.G.; Horton, D.; Scheldeman, G.; Mullen, C.; Jones, T.; Tight, M. ‘You feel unusual walking’: The invisible presence of walking in four English cities. J. Transp. Health 2014, 1, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Mackett, R.; Gong, Y.; Kitazawa, K.; Paskins, J. Gender differences in children’s pathways to independent mobility. Child. Geogr. 2008, 6, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P.; Lancy, D.F.; Bjorklund, D.F. Decline in independent activity as a cause of decline in children’s mental welllbeing: Summary of the evidence. J. Pediatr. 2023, 260, 113352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerebine, A.; Fitton-Davies, K.; Lander, N. “Children are precious cargo; we don’t let them take any risks!”: Hearing from adults on safety and risk in children’s active play in schools: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolley, H. Watch this space! Designing for children’s play in public open spaces. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, D.; Singer, J.L.; D’Agnostino, H.; DeLong, R. Children's pastimes and play in sixteen nations: Is free-play declining? Am. J. Play 2009, 12, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Hadani, H. A new path to education reform: Playful learning promotes 21st-century skills in schools and beyond [Internet]. The Brookings Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-new-path-to-education-reform-playful-learning-promotes-21st-century-skills-in-schools-and-beyond/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Sandseter, E.B.; Kleppe, R.; Ottesen Kennair, L.E. Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: An evolutionary approach. Int. J. Play 2022, 12, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sando, O.J.; Kleppe, R.; Sandseter, E.B.H. Risky play and children’s well-being, involvement and physical activity. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1435–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky Play and Childrens Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Bundy, A. Reliability and validity of a new instrument to measure tolerance of everyday risk for children. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, L.L.; Ishikawa, T.; Masse, L.C.; Chan, G.; Brussoni, M. Risk Engagement and Protection Survey (REPS): Developing and validating a survey tool on fathers’ attitudes toward child injury protection and risk engagement. Inj. Prev. 2018, 24, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Alparone, F.R.; Cristallo, C.; Luigi, S. Parental perception of social risk and of positive potentiality of outdoor autonomy for children: The development of two instruments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Characteristics of risky play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, R.; Eryuzlu, S.; Livock, H.; Leduc, G.; Faulkner, G.; Trudeau, F.; Tremblay, M.S. Test-retest reliability and convergent validity of measures of children’s travel behaviours and independent mobility. J. Transp. Health 2017, 6, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, K.; van Aalst, I. Neighbourhood Factors in Children’s Outdoor Play: A Systematic Literature Review. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2022, 113, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J. Active Transport: Children and Young People. VicHealth. 2009. Available online: https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Active_transport_children_and_young_people_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Edensor, T. Introduction to geographies of darkness. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 22, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, J.; Duncan, S.; Schofield, G. Intergenerational change in children’s independent mobility and active transport in New Zealand children and parents. J. Transp. Health 2017, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, H.; Rutberg, S.; Mikaelsson, K.; Lindqvist, A.K. It’s about being the good parent: Exploring attitudes and beliefs towards active school transportation. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2020, 79, 1798113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litsmark, A.; Rahm, J.; Mattsson, P.; Johansson, M. Children’s independent mobility during dark hours: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrorie, P.; Mitchell, R.; Macdonald, L.; Jones, A.; Coombes, E.; Schipperijn, J.; Ellaway, A. The relationship between living in urban and rural areas of Scotland and children’s physical activity and sedentary levels: A country-wide cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrick, S.R.; Wood, L.; Villanueva, K.P.; Wood, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Christian, H. Nothing but fear itself. In Parental Fear as a Determinant Impacting on Child Physical Activity and Independent Mobility; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeppe, S.; Tranter, P.; Duncan, M.J.; Curtis, C.; Carver, A.; Malone, K. Australian children’s independent mobility levels: Secondary analyses of cross-sectional data between 1991 and 2012. Child. Geogr. 2016, 14, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrador-Colmenero, M.; Villa-González, E.; Chillón, P. Children who commute to school unaccompanied have greater autonomy and perceptions of safety. Acta Paediatrica. 2017, 106, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacilli, M.G.; Giovannelli, I.; Prezza, M.; Augimeri, M.L. Children and the Public Realm: Antecedents and Consequences of Independent Mobility in a Group of 11–13-Year-Old Italian Children. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón, E.; Moyano, N.; Lozano, A.; Cava, M.J. Parents’ Willingness and Perception of Children’s Autonomy as Predictors of Greater Independent Mobility to School. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Balboa, M.J.; Huertas-Delgado, F.J.; Herrador-Colmenero, M.; Cardon, G.; Chillón, P. Parental barriers to active transport to school: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Ferrao, T.; King, N. Individual, family, and neighborhood correlates of independent mobility among 7 to 11-year-olds. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.Y.; Witten, K.; Oliver, M.; Carroll, P.; Asiasiga, L.; Badland, H.; Parker, K. Social and built-environment factors related to children’s independent mobility: The importance of neighbourhood cohesion and connectedness. Health Place 2017, 46, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Carver, A.; Salmon, J.; Abbott, G.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Cleland, V.; Timperio, A. What predicts children’s active transport and independent mobility in disadvantaged neighbourhoods? Health Place 2017, 44, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Költő, A.; Gavin, A.; Kelly, C.; Nic Gabhainn, S. Transport to school and mental well-being of schoolchildren in Ireland. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 583613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Benevenuto, R.; Caulfield, B. Identifying hotspots of transport disadvantage and car dependency in rural Ireland. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, S.; Ahern, A.; Caulfield, B. The economic boom, bust and transport inequity in suburban Dublin, Ireland. Res. Transp. Econ. 2016, 57, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoldrick, P.; Caulfield, B. Examining the changes in car ownership levels in the Greater Dublin Area between 2006 and 2011. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2015, 3, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahan, R.A.; Mullan, E. Perceptions of the Built Environment and Active Travel in Children and Young People. Doctoral Dissertation, Waterford Institute of Technology, Waterford, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Moore, E.; Toumpakari, Z.; Sebire, S.J.; Thompson, J.L.; Lawlor, D.A.; Jago, R. Roles of mothers and fathers in supporting child physical activity: A cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Corbett, M.; Brison, R.J. Identifying predictors of medically-attended injuries to young children: Do child or parent behavioural attributes matter? Inj. Prev. 2009, 15, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairman, J.G., Jr.; Schultz, D.M.; Kirshbaum, D.J.; Gray, S.L.; Barrett, A.I. Climatology of size, shape, and intensity of precipitation features over Great Britain and Ireland. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 1595–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Met Éireann. The Irish Meteorological Service [Internet]. Annual Climate Statement for 2021. Dublin: Met Éireann. 2021. Available online: https://www.met.ie/annual-climate-statement-for-2021 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Bélanger, M.; Gray-Donald, K.; O’Loughlin, J.; Paradis, G.; Hanley, J. Influence of Weather Conditions and Season on Physical Activity in Adolescents. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, F.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Corder, K.; Ekelund, U.; Jones, A. The Changing Relationship between Rainfall and Children’s Physical Activity in Spring and Summer: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Symonds, J.; Sloan, S.; Cahoon, A.; Crean, M.; Farrell, E.; Davies, A.; Blue, T.; Hogan, J. Children’s School Lives: An Introduction, Report No. 1; University College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H.; Wyver, S.; Gibson, F. The influence of play context and adult attitudes on young children’s physical risk-taking during outdoor play. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 19, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, E.; Blatchford, P. School Break and Lunch Times and Young People’s Social Lives: A Follow-up National Study; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, G.; Bundy, A.; Wyver, S.; Villeneuve, M.; Tranter, P.; Beetham, K.; Ragen, J.; Naughton, G. Uncertainty in the school playground: Shifting rationalities and teachers’ sense-making in the management of risks for children with disabilities. Health Risk Soc. 2016, 18, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, M.; Boyle, B.; Lilja, M.; Prellwitz, M. Irish Schoolyards: Teacher’s Experiences of Their Practices and Children’s Play-“It’s Not as Straight Forward as We Think”. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2023, 17, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W. The case for play in schools: A review of the literature. Outdoor Play and Learning. 2021. Available online: https://outdoorplayandlearning.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-Case-For-Play-In-Schools-web-1-1.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

| Measures | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to Child | ||

| Mother | 292 | 83.43 |

| Father | 52 | 14.86 |

| Grandmother | 3 | 0.86 |

| Grandfather | 1 | 0.28 |

| Guardian | 1 | 0.29 |

| Age Range | ||

| Prefer not to say | 62 | 17.77 |

| 25–29 years | 3 | 0.86 |

| 30–34 years | 7 | 2 |

| 35–39 years | 51 | 14.61 |

| 40–44 years | 97 | 27.79 |

| 45–49 years | 102 | 29.23 |

| 50–54 years | 19 | 5.44 |

| 55–59 years | 4 | 1.15 |

| 60+ years | 4 | 1.15 |

| Educational Attainment Level | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 164 | 46.99 |

| Completed Primary school | 1 | 0.29 |

| Completed Secondary school | 15 | 4.3 |

| University training | 29 | 8.31 |

| Apprenticeship/Diploma/Certificate | 71 | 20.34 |

| Postgraduate or higher | 69 | 19.77 |

| Location Demographics | Count | Percent |

| Other | 64 | 18.34 |

| Large City (more than 100,000 people) | 97 | 27.79 |

| Smaller city (30,000–100,000 people) | 24 | 6.88 |

| Town (1000–29,999 people) | 96 | 27.51 |

| Small town community or village (<1000 people) | 25 | 7.16 |

| Rural (not small town) | 43 | 12.32 |

| Children in Household Demographics | Count | Percent |

| How many Children Live in your House? | ||

| 1 | 27 | 19.2 |

| 2 | 202 | 49.57 |

| 3 | 36 | 25.21 |

| 4 | 20 | 6.02 |

| Children under 8 | ||

| Yes | 228 | 65.33 |

| No | 121 | 34.67 |

| Children 9–16 in the household | ||

| Yes | 222 | 62.61 |

| No | 127 | 36.39 |

| Table of Active Transport and Independent Mobility Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures: | Category: | Count: | Percent: |

| School Travel | |||

| Method of travelling to school | Walk | 63 | 18.05 |

| Car | 92 | 26.36 | |

| Bicycle/Scooter | 17 | 4.87 | |

| Bus/Public Transport | 142 | 40.69 | |

| Other | 35 | 10.03 | |

| Method of travelling from school | Walk | 62 | 17.77 |

| Car | 93 | 26.65 | |

| Bicycle/Scooter | 24 | 6.88 | |

| Bus/Public Transport | 139 | 39.83 | |

| Other | 31 | 8.88 | |

| Person accompanying child to school | On their own | 64 | 18.34 |

| Adult(s) | 27 | 7.74 | |

| Sibling(s) | 202 | 57.90 | |

| Friend(s) | 36 | 10.32 | |

| Other | 20 | 5.73 | |

| Person accompanying child from school | On their own | 62 | 17.77 |

| Adult(s) | 18 | 5.16 | |

| Sibling(s) | 128 | 36.68 | |

| Friend(s) | 19 | 5.44 | |

| Other | 27 | 7.74 | |

| Other Travel | |||

| Permitted to travel alone within walking distance | Yes | 113 | 32.38 |

| No | 157 | 44.99 | |

| N/A | 79 | 22.64 | |

| Permitted to cross main roads alone | Yes | 133 | 38.11 |

| No | 149 | 42.69 | |

| N/A | 67 | 19.20 | |

| Permitted to cycle on main roads alone | Yes | 39 | 11.17 |

| No | 237 | 67.91 | |

| N/A | 73 | 20.92 | |

| Permitted out alone after dark | Yes | 18 | 5.16 |

| No | 264 | 75.64 | |

| N/A | 67 | 19.20 | |

| Permitted to travel by bus alone (excluding school buses) | Yes | 36 | 10.32 |

| No | 232 | 66.48 | |

| N/A | 81 | 23.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Armstrong, F.; Barrett, M.J.; Gaul, D.; D’Arcy, L. Parental Attitudes to Risky Play and Children’s Independent Mobility: Public Health Implications for Children in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071106

Armstrong F, Barrett MJ, Gaul D, D’Arcy L. Parental Attitudes to Risky Play and Children’s Independent Mobility: Public Health Implications for Children in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071106

Chicago/Turabian StyleArmstrong, Fiona, Michael Joseph Barrett, David Gaul, and Lorraine D’Arcy. 2025. "Parental Attitudes to Risky Play and Children’s Independent Mobility: Public Health Implications for Children in Ireland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071106

APA StyleArmstrong, F., Barrett, M. J., Gaul, D., & D’Arcy, L. (2025). Parental Attitudes to Risky Play and Children’s Independent Mobility: Public Health Implications for Children in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071106