The Effect of Exposure to Alcohol Media Content on Young People’s Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

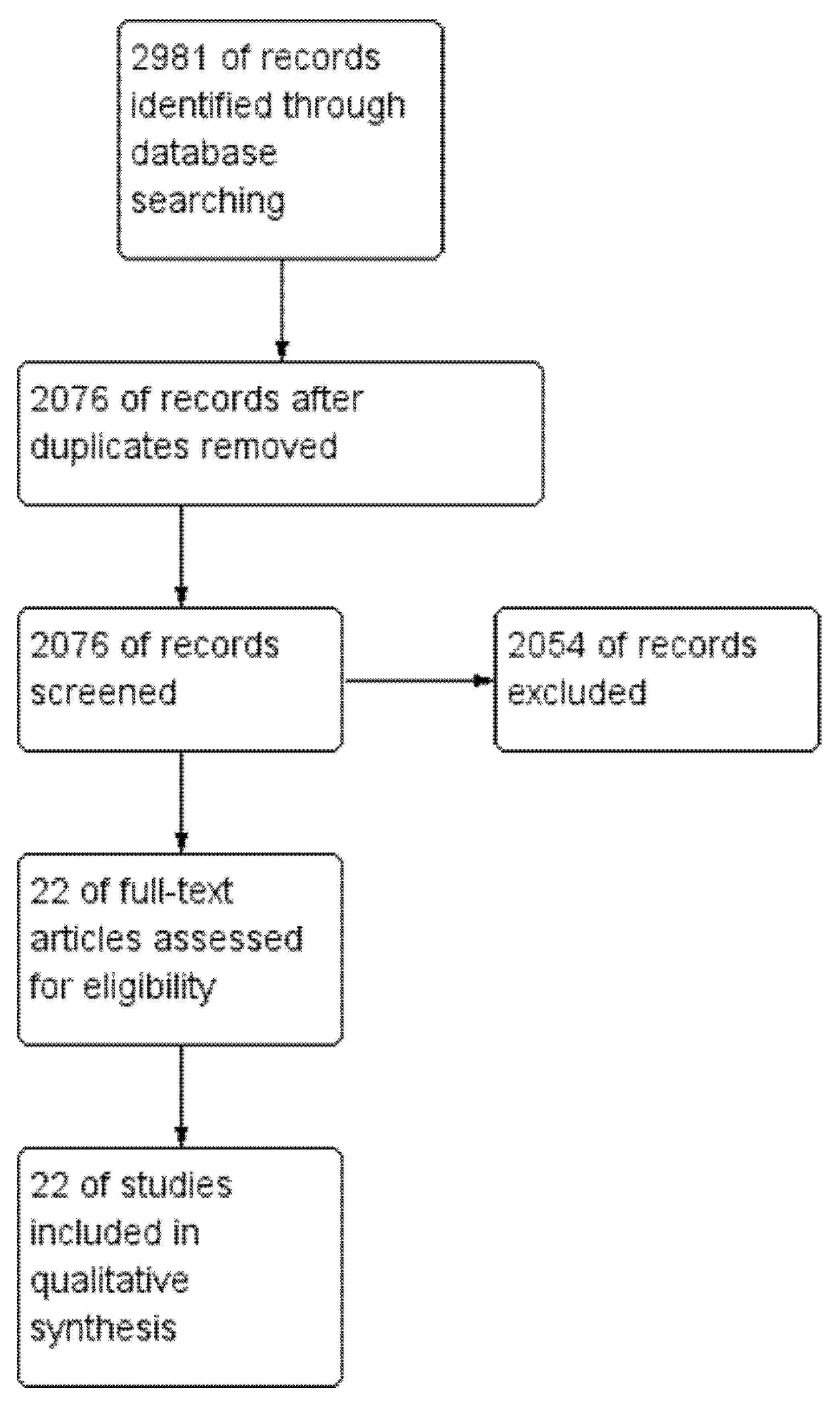

2. Materials and Methods

- A—No or few flaws: The study’s credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability are high.

- B—Some flaws, unlikely to affect the credibility, transferability, dependability, and/or confirmability of the study.

- C—Some flaws, which may affect the credibility, transferability, dependability, and/or confirmability of the study.

- D—Significant flaws, which are likely to affect the credibility, transferability, dependability, and/or confirmability of the study.

3. Results

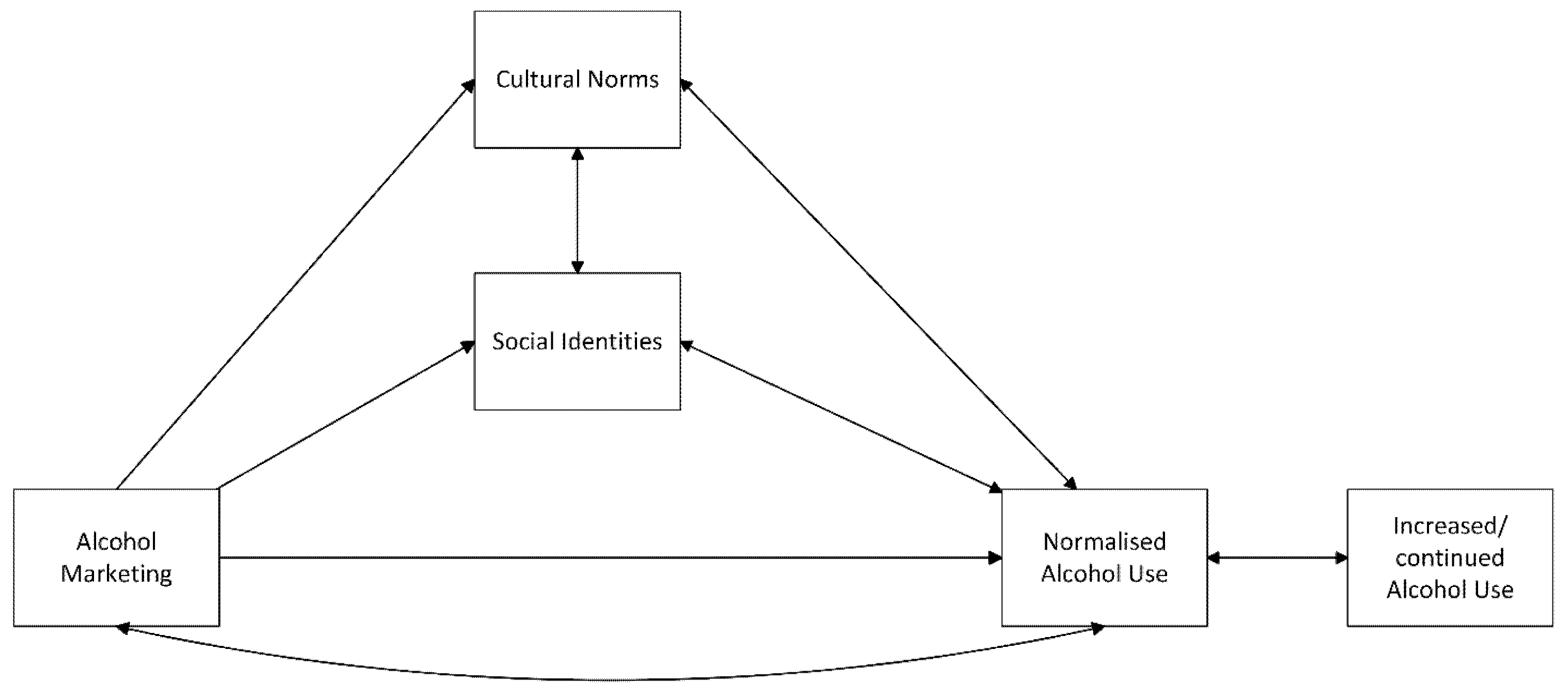

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Limb, M. WHO blames tobacco, processed food, fossil fuel, and alcohol industries for 2.7 m deaths a year in Europe. BMJ 2024, 385, q1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-Specific Deaths in the UK: Registered in 2023. 2025. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/alcoholrelateddeathsintheunitedkingdom/registeredin2023 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Public Health England. Alcohol Treatment in England 2013-14; 2014; p. 3. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20170807150623/http://www.nta.nhs.uk/uploads/adult-alcohol-statistics-2013-14-commentary.pdf. (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bonomo, Y.A.; Bowes, G.; Coffey, C.; Carlin, J.B.; Patton, G.C. Teenage drinking and the onset of alcohol dependence: A cohort study over 7 years. Addiction 2004, 99, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. No Level of Alcohol Consumption is Safe for Our Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Anderson, P.; de Bruijn, A.; Angus, K.; Gordon, R.; Hastings, G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009, 44, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, R.L.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Barker, A.; Brown, O.; Langley, T. A rapid literature review of the effect of alcohol marketing on people with, or at increased risk of, an alcohol problem. Alcohol Alcohol. 2024, 59, agae045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Park, S.; Smith, S.; Hendriks, H.; Dong, Y. Social media use and alcohol consumption: A 10-year systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, A.B.; Bal, J.; Ruff, L.; Murray, R.L. Exposure to tobacco, alcohol and ‘junk food’ content in reality TV programmes broadcast in the UK between August 2019–2020. J. Public Health 2022, 45, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.B.; Bal, J.; Murray, R.L. A Content Analysis and Population Exposure Estimate Of Guinness Branded Alcohol Marketing During the 2019 Guinness Six Nations. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021, 56, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.B.; Breton, M.O.; Murray, R.L.; Grant-Braham, B.; Britton, J. Exposure to ‘Smokescreen’ marketing during the 2018 Formula 1 Championship. Tob. Control. 2019, 28, e154–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerhouni, O.; Begue, L.; O’Brien, K.S. How alcohol advertising and sponsorship works: Effects through indirect measures. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Jetten, J.; Cruwys, T.; Dingle, G.A.; Haslam, S.A.; Mahmood, L. The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure; Routeledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pegg, J.K.; O’Donnell, A.W.; Lala, G.; Barber, B.L. The role of online social identity in the relationship between alcohol-related content on social networking sites and adolescent alcohol use. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identification, self categorization and social influence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 1, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. ‘It’s Everywhere’: Considering the Impact of Alcohol Marketing on People with Problematic Alcohol Use. 2023. Available online: https://www.ias.org.uk/2023/03/01/its-everywhere-considering-the-impact-of-alcohol-marketing-on-people-with-problematic-alcohol-use/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Pereira, S.S.; Lyons, A. Rainbow-Washing or Genuine Allyship? How Alcohol Companies Target the LGBTQ+ Community. 2025. Available online: https://www.ias.org.uk/2025/03/10/rainbow-washing-or-genuine-allyship-how-alcohol-companies-target-the-lgbtq-community/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, D.R. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesising qualitative studies. Counterpoints 1999, 44, 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Pratical Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, K.; Hellings, C.; Foley, N.; Teasell, R. The experience of living with stroke: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; Downe, S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery 2006, 22, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downe, S.; Simpson, L.; Trafford, K. Expert intrapartum maternity care: A meta-synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D.; Devane, D. A meta-synthesis of midwife-led care. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayyan. Faster Systematic Literature Reviews. 2025. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- MacArthur, G.J.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Qualitative exploration of the intersection between social influences and cultural norms in relation to the development of alcohol use behaviour during adolescence. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e030556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.C.; Goodwin, I.; McCreanor, T.; Griffin, C. Social networking and young adults’ drinking practices: Innovative qualitative methods for health behavior research. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, R.I.; Stead, M.; Eadie, D. “I Wouldn’t Be Friends with Someone If They Were Liking Too Much Rubbish”: A Qualitative Study of Alcohol Brands, Youth Identity and Social Media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Sumnall, H. ‘If I don’t look good, it just doesn’t go up’: A qualitative study of young women’s drinking cultures and practices on Social Network Sites. Int. J. Drug Policy 2016, 38, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.; Shucksmith, J.; Baker, R.; Kaner, E. ‘Hidden Habitus’: A Qualitative Study of Socio-Ecological Influences on Drinking Practices and Social Identity in Mid-Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niland, P.; Lyons, A.C.; Goodwin, I.; Hutton, F. ‘See it doesn’t look pretty does it?’ Young adults’ airbrushed drinking practices on Facebook. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steers, M.N.; Mannheim, L.C.; Ward, R.M.; Tanygin, A.B. The alcohol self-presentation model: Using thematic qualitative analysis to elucidate how college students self-present via alcohol-related social media posts. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022, 41, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewpramkusol, R.; Senior, K.; Chenhall, R.; Nanthamongkolchai, S. Young Thai People’s Exposure to Alcohol Portrayals in Society and the Media: A Qualitative Study for Policy Implications. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torronen, J.; Roumeliotis, F.; Samuelsson, E.; Room, R.; Kraus, L. How do social media-related attachments and assemblages encourage or reduce drinking among young people? J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbili, E.W.; Williams, C. Awareness of alcohol advertisements and perceived influence on alcohol consumption: A qualitative study of Nigerian university students. Addict. Res. Theory 2017, 25, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Ross-Houle, K.M.; Begley, E.; Sumnall, H. An exploration of alcohol advertising on social networking sites: An analysis of content, interactions and young people’s perspectives. Addict. Res. Theory 2017, 25, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niland, P.; McCreanor, T.; Lyons, A.C.; Griffin, C. Alcohol marketing on social media: Young adults engage with alcohol marketing on Facebook. Addict. Res. Theory 2016, 25, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbili, E.W.; Williams, C. Anywhere, everywhere: Alcohol industry promotion strategies in Nigeria and their influence on young people. Afr. J. Drug Alcohol Stud. 2016, 15, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.; Moodie, C.; Eadie, D.; Hastings, G. Critical social marketing—The impact of alcohol marketing on youth drinking: Qualitative findings. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2010, 15, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.M.; Bellis, M.; Sumnall, H. Young peoples’ perspective on the portrayal of alcohol and drinking on television: Findings of a focus group study. Addict. Res. Theory 2013, 21, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiters, E.D.; Treno, A.J.; Grube, J.W. Alcohol advertising and youth: A focus-group analysis of what young people find appealing in alcohol advertising. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2001, 28, 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.J. Exploring Life Themes and Myths in Alcohol Advertisements through a Meaning-Based Model of Advertising Experiences. J. Advert. 1998, 27, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, P.P.; Leathar, D.S.; Scott, A.C. Ten-To Sixteen-Year-Olds’ Perceptions of Advertisements for Alcoholic Drinks. Alcohol Alcohol. 1988, 23, 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, L.R.; Orlandi, M.A. Alcohol advertising and adolescent drinking. Alcohol Health Res. World 1987, 12, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Vanherle, R. A qualitative study among adolescents to unravel the perceived group dynamics underlying the use of closed SNS stories and the sharing of alcohol related content. Mass Commun. Soc. 2025, 28, 732–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, J.E.; López, G.; Doucette, H.; Pielech, M.; Corcoran, E.; Egbert, A.; Wray, T.B.; Gabrielli, J.; Colby, S.M.; Jackson, K.M. Adolescents’ perceptions of alcohol portrayals in the media and their impact on cognitions and behaviors. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2023, 37, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, E.; Doucette, H.; Merrill, J.E.; Pielech, M.; López, G.; Egbert, A.; Nelapati, S.; Gabrielli, J.; Colby, S.M.; Jackson, K.M. A qualitative analysis of adolescents’ perspectives on peer and influencer alcohol-related posts on social media. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023, 43, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Sumnall, H.; Begley, E.; Jones, L. A Rapid Narrative Review of Literature on Gendered Alcohol Marketing and Its Effects: Exploring the Targeting and Representation of Women; Institute of Alcohol Studies: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Standards Authority. The BCAP Code Section 19—Alcohol. 2025. Available online: https://www.asa.org.uk/type/broadcast/code_section/19.html (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Advertising Standards Authority. The CAP Code—18 Alcohol. 2025. Available online: https://www.asa.org.uk/type/non_broadcast/code_section/18.html (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Ofcom. The Ofcom Broadcasting Code (With the Cross-Promotion Code and the On-Demand Programme Service Rules). 2023. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/broadcast-standards/broadcast-code/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Ofcom. Statutory Rules and Non-Binding Guidance for Providers of On-Demand Programme Services (ODPS). 2021. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0029/229358/ODPS-Rules-and-Guidance.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Ofcom. Quick Guide to Illegal Content Codes and Practice. 2025. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/online-safety/illegal-and-harmful-content/codes-of-practice/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. SAFER: Enforce Bans or Comprehensive Restrictions on Alcohol Advertising, Sponsorship, and Promotion. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/SAFER/alcohol-advertising (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Alfayad, K.; Murray, R.L.; Britton, J.; Barker, A.B. Population exposure to alcohol and junk food advertising during the 2018 FIFA World Cup: Implications for public health. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.; Opazo-Breton, M.; Thomson, E.; Britton, J.; Grant-Braham, B.; Murray, R.L. Quantifying alcohol audio-visual content in UK broadcasts of the 2018 Formula 1 Championship: A content analysis and population exposure. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, R.; Breton, M.O.; Britton, J.; Cranwell, J.; Grant-Braham, B. Carlsberg alibi marketing in the UEFA euro 2016 football finals: Implications of probably inappropriate alcohol advertising. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Concept | Adolescents | Alcohol | Media |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synonyms | Teenagers | Drinking | Mass Media |

| Broader | Young Adults Young People Youth | Ethanol | Entertainment |

| Narrower | Alcohol Use Alcohol Experimentation Alcohol Consumption Alcohol Misuse | Television TV Programmes Films Movies Cinema Digital Media Social Media | |

| Related Terms | Intoxication Binge Drinking Alcoholics Alcoholism | Social Marketing Celebrity Endorsement Product Placement Advertising Marketing Influencer Sponsorship |

| Study | Downe & Walsh Rating | Participants | Age Range | Exposure | Analysis | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macarthur et al. 2020 [28] | A | 42 | 14–18 | Films, Social Media, Peer Influences | Thematic Analysis | England |

| Lyons et al. 2015 [29] | A | 141 group discussions 23 individual interviews | 18–25 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis Foucauldian Discourse Analysis | New Zealand |

| Purves et al. 2018 [30] | B | 48 | 14–17 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | Scotland |

| Atkinson & Sumnall. 2016 [31] | A | 37 | 16–21 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | England |

| Scott et al. 2017 [32] | A | 31 | 13–17 | Any Marketing | Thematic Analysis | England |

| Niland et al. 2014 [33] | B | 7 | 18–25 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | New Zealand |

| Steers et al. 2022 [34] | C | 15 | 18–26 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | USA |

| Kaewpramkusol et al. 2019 [35] | C | 72 | 20–24 | Any Marketing, Social Media | Content analysis to identify themes | Thailand |

| Torronen et al. 2021 [36] | B | 56 | 15–19 | Social Media | Actor-Network Theory Analysis | Sweden |

| Dumbili & Williams 2017 [37] | B | 31 | 19–23 | TV Marketing, Films, Sports Sponsorship, Physical Marketing | Thematic Analysis | Nigeria |

| Atkinson et al. 2017 [38] | A | 70 | 16–21 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | England |

| Niland et al. 2017 [39] | B | 7 | 18–25 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | New Zealand |

| Dumbili & Williams 2016 [40] | B | 31 | 19–23 | All Marketing | Thematic Analysis | Nigeria |

| Gordon et al. 2010 [41] | C | 64 | 13–15 | All Marketing | Thematic Analysis | Unclear |

| Atkinson et al. 2013 [42] | B | 114 | 11–18 | TV Content and Marketing | Thematic Analysis | England |

| Waiters et al. 2001 [43] | C | 97 | 9–15 | TV Marketing | Categorical summaries | USA |

| Parker 1998 [44] | C | 7 | 18–22 | TV Marketing | Summary of patterns and themes | USA |

| Aitken et al. 1988 [45] | C | 150 | 10–16 | TV Marketing | Not mentioned | Scotland |

| Lieberman & Orlandi 1987 [46] | C | 2766 | 11–12 | TV Marketing | Content Analysis | USA |

| Vanherle 2025 [47] | A | 32 | 15–18 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | Belgium |

| Merril et al. 2023 [48] | A | 40 | 15–19 | All Media | Thematic Analysis | USA |

| Corcorran et al. 2024 [49] | A | 40 | 15–19 | Social Media | Thematic Analysis | USA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Getliff, S.; Barker, A.B. The Effect of Exposure to Alcohol Media Content on Young People’s Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071078

Getliff S, Barker AB. The Effect of Exposure to Alcohol Media Content on Young People’s Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071078

Chicago/Turabian StyleGetliff, Sophie, and Alex B. Barker. 2025. "The Effect of Exposure to Alcohol Media Content on Young People’s Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071078

APA StyleGetliff, S., & Barker, A. B. (2025). The Effect of Exposure to Alcohol Media Content on Young People’s Alcohol Use: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071078