Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a widespread issue with severe consequences for women’s well-being. This scoping review synthesizes research on coping strategies among female IPV survivors, evaluates measurement approaches, and assesses the applicability of the 11 families of coping framework. Analyzing 27 studies (2017–2022) from the Scopus database, we identified key coping patterns. In response to the first research question, the review revealed methodological diversity, with qualitative interviews predominating (55.56% of studies) alongside quantitative measures such as the Brief-COPE and IPV Strategies Index. All documented coping strategies were successfully categorized using Skinner’s framework, demonstrating its comprehensive utility for IPV research. This complete categorization directly answers our second research question, confirming the framework’s effectiveness for classifying IPV coping strategies. By using this framework, we identified key coping patterns, with seeking social support emerging as the most prevalent strategy (88.89% of studies), followed by escape–avoidance (55.56%) and problem-solving (44.44%). The findings underscore the value of adopting a standardized classification system to enhance consistency across studies and improve comparative analyses. The study contributes to theoretical development by validating Skinner’s model in IPV contexts and offers practical guidance for future research design. By demonstrating the universal applicability of the 11 families of coping, this scoping review provides a foundation for systematic investigations of coping mechanisms and informs targeted support interventions for survivors.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Study

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is one of the most common forms of violence against women, encompassing physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression by a current or former romantic partner [1,2]. Globally, an estimated 27% of women aged 15–49 have experienced IPV at least once in their lifetime, with prevalence rates varying significantly by region. Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia report the highest rates (33%), followed by Northern Africa (30%) and the Americas (25%), while high-income regions such as Europe show lower rates (16–23%) [3]. Beyond its immediate physical and psychological harm, IPV perpetuates a cycle of violence, as children exposed to domestic violence are more likely to become either perpetrators or victims later in life [4,5].

To manage the trauma of abuse and its aftermath, survivors employ various coping strategies which can range from problem-solving approaches to emotional regulation [6]. Coping is a dynamic, multidimensional process influenced by individual and situational factors [7]. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, individuals assess stressful situations, select coping strategies, and evaluate their effectiveness before deciding whether to adjust their approach [8]. This model highlights the adaptive nature of coping, where outcomes shape future responses.

1.2. Research Gaps

Despite extensive research on coping mechanisms, a significant gap remains in how these strategies are systematically classified for IPV survivors. Existing frameworks often rely on oversimplified distinctions, such as problem-focused versus emotion-focused coping, which fail to capture the complexity of real-world responses. For example, a strategy like “planning” can serve both problem-solving and emotional-regulation functions, making it difficult to categorize under traditional models. Additionally, the lack of a standardized classification system has led to inconsistencies across studies, with overlapping or vaguely defined coping strategies complicating comparative analysis [9].

This study addresses these limitations by applying the 11 families of coping, a theoretically grounded and empirically validated system designed to minimize overlap while accommodating diverse coping behaviors. Unlike previous models, this classification provides clear, mutually exclusive categories, ensuring more precise analysis [10]. The framework excludes only one of the original 12 families—delegation—as it applies exclusively to children, leaving 11 categories relevant to adult IPV survivors.

1.3. Skinner et al. (2003)’s 11 Families of Coping

The 11 families of coping are defined as follows [10]:

Accommodation involves adjusting personal expectations to situational constraints through strategies like cognitive restructuring, minimization, and acceptance. Escape encompasses disengagement from stress via cognitive avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking. Helplessness reflects surrender of control through passivity, confusion, and pessimism. Information seeking includes educating oneself about the stressful situation through monitoring and observation. Negotiation represents compromise attempts through priority-setting, persuasion, and deal-making. Opposition involves externalizing behaviors like anger, aggression, and blaming others.

Problem-solving incorporates active approaches including planning, logical analysis, and persistent effort. Self-reliance focuses on internal regulation through emotional and behavioral control. Seeking support entails reaching out to various networks for instrumental help or emotional comfort. Social withdrawal involves isolating oneself through avoidance and concealment. Submission represents relinquishing control through rumination and intrusive thoughts.

- Aims of the study

Based on the comments that many coping strategies have been identified due to the different measurements used, it is assumed that similar comments can also apply to studies on coping in the subject of IPV [9]. Accordingly, this scoping review aimed to review recent literature on IPV to examine various coping and measurements used by researchers in these studies. In addition, we also aimed to examine whether various coping strategies used by IPV survivors can be classified based on the 11 families of coping [10]. This framework was proposed by Skinner et al. due to the extensive number of coping strategies reported and thus underscored the need to have a framework to classify these various coping strategies. This framework was particularly suitable for our study because, like the broader literature Skinner et al. addressed, IPV research has similarly documented a wide variety of coping strategies requiring systematic organization.

Accordingly, the research questions of this scoping review are as follows:

RQ1: What are the coping strategies used by female IPV survivors?

RQ2: What are the coping measurements used in IPV research?

RQ3: Can the different coping strategies used by women IPV survivors be categorized into the 11 coping strategies as proposed by Skinner et al. [10]?

2. Materials and Methods

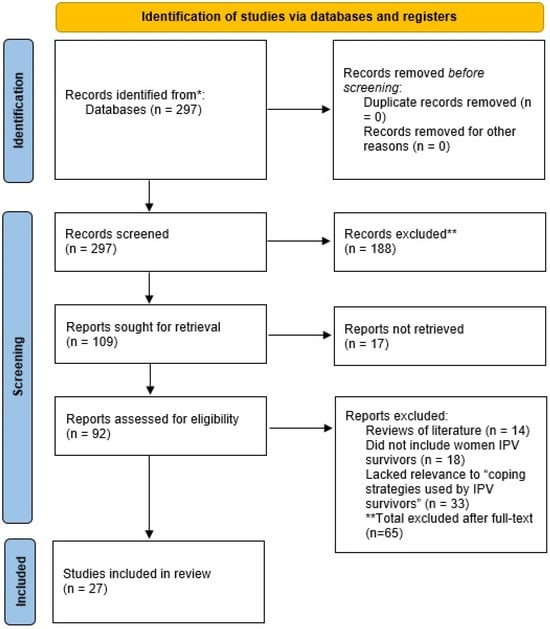

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We have adhered to the PRISMA 2020 checklist and flow diagram to ensure transparency and completeness in our reporting. Specifically, the PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process, including the initial search results, the number of studies included and excluded at each stage, and the reasons for exclusion. The PRISMA checklist, available at https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-checklist (accessed on 18 April 2025), guides us in reporting all essential aspects of the scoping review, including the research question, search methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, and synthesis of findings.

This scoping review on the coping strategies used by female IPV survivors was conducted to gather evidence in the literature in the field of psychology from the Scopus database published between 2017 to 2022. This scoping review was guided by the six-stage methodological framework [11], which includes (i) identifying the research question, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) selecting eligible studies, (iv) charting of data, and (v) collating and summarizing the results.

- Identifying Relevant Studies

The search for articles was limited to several qualifying criteria. Only journal articles that were written in English and were published on the electronic database Scopus were selected for consideration. The Scopus database was selected as it has a larger dataset with a wider journal range [12] and has a search option that allows users to better identify the material they require based on specific requirements [13]. While other databases such as Web of Science, PsycINFO and PubMed were considered, Scopus was ultimately selected as it had a wider overall coverage and indexed a greater number of sources not indexed in other databases [14,15]. The articles were then further filtered to those published between 2017–2022.

Two keywords were used in the search of articles, which are “coping” and “intimate partner violence”, and only articles published between the years 2017 to 2022 in the field of psychology were selected. This allowed for the search of articles to be general enough that no potentially relevant articles were missed out on. After searching the keywords “coping” and “intimate partner violence”, 297 articles were identified as relevant studies.

- Selection of Eligible Studies

The 297 articles were reviewed by the researchers to ensure the content of the articles was relevant to the aim and research question of this study, which was to investigate the coping strategies used by women IPV survivors. Further eligibility criteria were applied to ensure that the selected articles were able to provide the necessary information relevant to the study.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) participants must be adult or adolescent women who have experienced intimate partner violence (regardless of marital status)—studies including both male and female participants were eligible, provided they included female IPV survivors; (2) articles must report on the specific coping strategies used by IPV survivors; (3) articles must be original research papers; and (4) articles must be published in English in the Scopus database from 2017 to 2022 (which was when the scoping review was conducted).

The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) articles outside the psychology discipline; (2) studies where female IPV survivors were not the primary sample; (3) research that did not specifically examine coping strategies among female IPV survivors; (4) articles that are reviews of prior literature; and (5) articles not published in English in Scopus between 2017 and 2022. These exclusions ensured the scoping review focused exclusively on relevant psychological research about women’s coping mechanisms for IPV during the specified timeframe.

Among the 297 articles identified as relevant articles, two reviewers conducted a full-text assessment of 95 articles. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 65 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 14 were literature reviews, 18 did not focus on female IPV survivors, and 33 lacked relevant data about coping strategies. Ultimately, 27 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the scoping review. The screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screening process of articles.

- Charting the Data

A table (Table 1) was constructed to facilitate the charting of data. Table 1 consisted of the necessary information, which included the title of the articles, the design of the study, the method by which the data was collected in the study, sample size and basic demographic information of the sample, the country in which the study was conducted in, and relevant findings that could answer the research question of this study.

Table 1.

Summary of articles.

- Data Synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity in measuring coping strategies among IPV survivors, a narrative synthesis was conducted, which included summarizing results in structured tables that compared study designs and findings (see Table 1) and thematically analyzing consistencies and contradictions across studies. Codes regarding coping strategies were generated from the articles reviewed.

- Terminology Clarification

To ensure conceptual clarity, we adopt the following definitions throughout this study: (1) ‘Coping strategies’ refer to specific behaviors or cognitive efforts survivors employ to manage IPV-related stress (for example, support seeking, escape); (2) ‘Measurements’ denote the tools/methods used to assess these strategies (for example, Brief-COPE, interviews); and (3) ‘Systems’ describe overarching classification frameworks (for example, Skinner’s 11 families). These terms are mutually exclusive and applied consistently across analysis and reporting.

3. Results

A total of 27 articles that were published between 2017 and 2022 met the inclusion criteria. The included articles are as below in Table 1.

3.1. Coping Strategies Used by Survivors

As shown in Table 1, different coping strategies have been reported, such as social support from family and friends, having safety plans, engaging in self-blame, physically resisting the abuser, and many more.

3.2. Measurements Used in IPV Research

As summarized in Table 1, different researchers chose to use different measurements to collect data on survivors’ use of coping strategies. Among the 27 studies, 18 studies used the qualitative research method, 7 studies used the quantitative research method, and 2 studies chose to use a mixed-method. For the studies that used the qualitative research method, 15 of them chose to interview survivors on their experiences and the coping strategies they used (55.56%), while 2 other studies used focus groups to collect data (7.41%). Besides that, one study chose to collect data using virtual ethnography by exploring social interactions occurring in online or digital environments (3.70%) [33].

For the studies that used the quantitative research method, three studies chose to develop their survey items (11.11%), while one study used the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) (3.70%) [24]. Other measurements used by researchers included the Cognitive Processing of Trauma Scale (POTS) (3.70%) [22], Intimate Partner Violence Strategies Index (IPVSI) (3.70%) [7], Ways of Coping Scale (3.70%) [30] and the Measure of Affect Regulation Styles (MARS) (3.70%) [35]. Two studies chose to use a mixed-method (7.41%), whereby one study used a combination of interviews and the Measure of Affect Regulation Styles (MARS) [35], while another study used a combination of a self-developed survey and interview to collect data (3.70%) [21].

3.3. Codes Categorized Under Skinner’s 11 Families of Coping

After reviewing the 27 articles included in the scoping review, the primary researcher extracted data from the articles regarding coping strategies used by IPV survivors and carried out coding of these data. An example of coding is as follows:

Original text from article: “I kept saying this can’t be happening, this can’t be real.” Ginny could not believe that her partner was becoming verbally abusive. [denial]

After coding all the coping strategies that were reported in the 27 articles reviewed, the reviewers attempted to arrange these codes in a more systematic way by reframing the coping strategies according to Skinner’s 11 families of coping. Two independent reviewers examined the codes generated and categorized them based on the 11 families of coping. While there were disagreements over the categorization of a particular coping strategy, a third reviewer was brought in to give their opinion, thereby coming to a decision. Overall, all the codes were able to be categorized according to the 11 families of coping, which can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Coping strategies according to Skinner’s 11 families of coping.

Accommodation. Some coping strategies under this family of coping include distraction and cognitive restructuring [16,31,37].

Distraction. Some coping strategies reported in the reviewed articles can be categorized under distraction, including filling time with community activities or getting a job [16], engaging in education or employment after leaving the relationship [39], engaging in activities such as cooking, watching television, listening to music, or performing housework [34], and engaging in various physical activities and hobbies [40].

Cognitive Restructuring. One coping strategy that can be categorized as cognitive restructuring is attributing a new identity to the abusive partner [28]. Survivors cope with the disgust they feel towards their abusive partner by attributing a new role or identity to the abuser, which puts distance in the relationship between the survivor and the abuser. For example, one survivor re-identified her abusive partner as “the father of my child” rather than “my husband”. This allowed the survivors to redefine the connection they once had with the abuser. In addition to that, the survivors construct a new identity by being involved in new relationships so that they can identify themselves with new roles, building up their self-worth and self-esteem [28,37]. Similarly, women IPV survivors engaged in remarriage to regain the social status they lost through divorcing the abusive partner [17]. Another strategy included helping other women going through similar abusive situations to find meaning and purpose in their lives [31,37]). Survivors also engaged in positive cognitive restructuring [22].

Escape. The coping strategies under this category include protective actions by survivors to avoid further provoking the abuser [6], traveling back and forth from the marital and natal home or leaving the marital home [7,18,34], avoiding abusers at certain times or staying with families and friends [36], false hope that the situation would become better and their abusers would stop abusing them [20,34], denying the abuse they experienced, blocked feelings related to the abuse [20,24], physical avoidance from their abusive partners by locking themselves in rooms to avoid their husbands when they came home drunk [19] or sleeping in separate beds, staying silent to prevent interacting with their husbands, eating disorders and substance abuse [20,37,38].

Helplessness. An example of this category of coping strategy present in this scoping review is disengagement from one’s self [24]. Survivors reported experiencing a disrupted self-image during their exposure to abuse and felt disgusted at their changed selves. As such, they tried to cope with this disgust through alienation from the self. They described how they felt like they were acting out of identity when they could not resist the abuse from the abuser and became estranged from themselves during and after the violence. Women IPV survivors also engaged in silence to not be stigmatized by their community, as abuse is considered a disgrace to women in certain cultures [18].

Information Seeking. Information seeking involves survivors constantly monitoring their surroundings and establishing safety plans for security [27], taking precautions such as keeping important contact numbers, stashing money and valuables, and maintaining an escape plan [36], and seeking information to understand control and power dynamics in abusive relationships, enabling them to make sense of their past and move forward [37].

Negotiation. Negotiation involves survivors involving family members to intervene and negotiate with the abuser, such as seeking joint meetings between their in-laws and birth family to resolve conflicts with abusive husbands [34], or enlisting their birth family to negotiate with abusive partners to stop the abuse [29]. Additionally, survivors attempted direct negotiation with their partners to halt the abuse [7,39], admitted wrongdoing and apologized to their partners to settle issues [18], or employed strategies such as being submissive and complying with their abusers’ demands to maintain peace and avoid [7,19,36,39].

Opposition. Opposition took the form of active resistance behaviors among survivors, such as physically hitting back, verbally resisting or standing up to the abusers, rejecting their apologies, using contraception secretly, and also reporting the abusers’ animal abuse behavior to the police [38]. For example, survivors engaged in opposition strategies by fighting back physically against their abusers and refusing to do what the abuser asked [7].

Problem-solving. Different coping strategies from reviewed articles have been identified and categorized as problem-solving. These coping strategies include seeking financial independence to escape the abusive relationships [6,7], being hyper-vigilant of their behavior to avoid being abused [39], actually leaving the abusive relationship or getting a divorce [17,18,29,37,38,39] and trying to gain back control of their lives, whether by becoming self-empowered by being employed to gain economic freedom or taking custody of their children to maintain their children or their relationships [17].

Seeking Support. In terms of seeking support, different sources of support have been identified from the articles reviewed, such as advice the women received from their friends and family [18,19], the positive feedback and advice they received from their loved ones [16], intervention from their friends and family when the abuse intensified, or when they felt they were unable to reach out for help from the police, as their husbands’ reputation would be affected [29,32].

Besides that, social media is another important source of social support for coping. For example, survivors were able to share their stories of abuse, receive emotional support, and obtain resourceful information and support from members of Facebook communities of IPV survivors [33]. Besides that, these Facebook groups were also a place of resourceful information and support for the women to report the abuse to the authorities. Focus groups consisting of IPV survivors were also helpful to the women in coping with the trauma, as this allowed the women to share similar experiences and feelings that resulted from the abuse [20,37,40]. Parent groups consisting of IPV survivors with children were also helpful to women in increasing their coping capabilities, as involvement in these groups gave them a sense of release when sharing or listening to experiences of abuse, as well as gaining confidence and hope in knowing how to seek support and communicate with their children. This is further facilitated by the professional assistance given in the parent group, which allowed the women to better understand and process their experiences [21].

Moreover, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), medical centers, or even shelters are another source of social support for screening for abuse, care and guidance [6], and counseling services [19,27,37,40]. Besides that, governmental departments or authoritative bodies also provide social support including frightening the abuser, filing complaints or calling the police to stop them from abusing the women, obtaining orders of protection, or contacting lawyers to settle legal issues stemming from the abuse [6,16,23,32].

Furthermore, religion also offers support to women in various ways, such as praying to God to change their partners’ abusive behavior [18,25], praying for inner peace, praying to seek guidance from God on whether to leave their husbands, confiding in their friends at church, or in pastors and religious leaders about their experiences [25], turning to the Qur’an (Islam holy bible) for wisdom and perseverance to cope with the [29,31,32], and intervention, advice and even spiritual coping strategies from religious leaders [29,31,32].

Self-reliance. Self-reliance includes coping strategies such as controlled expression of emotion, self-control, and self-reward to focus on the situation and find solutions [35]. Some survivors tried not to cry during abuse to avoid arguments with the abuser [7]. Others used silence for peace of mind and crying as an emotional outlet to relieve negative emotions [18,34].

Social Withdrawal. Social withdrawal includes avoiding sharing their experiences of abuse with friends or colleagues due to fears of privacy exposure [25], avoiding seeking help from family and friends to prevent being blamed for the abuse [37], and avoiding approaching religious imams for help because exposing their husbands’ abuse would harm their reputations and was culturally unacceptable [31].

Submission. This category includes coping strategies such as engaging in self-blame to cope with the abuse they experienced [19,24,30], and felt they were at fault which resulted in them being abused by their partner [20].

3.4. Other Findings

Most Frequently Reported Families of Coping. Based on Table 2, the most reported coping strategy was support seeking (88.89%), with escape avoidance (55.56%) and problem-solving (44.4%) coming in as second and third.

The Countries. Out of the 27 articles included, 7 studies were conducted in Asia (Malaysia: 1; India: 3; Hong Kong: 1; Indonesia: 2), 7 in Europe (Poland: 1; Greece: 1; United Kingdom: 3; Spain: 1; Bosnia and Herzegovina: 1), 3 in the Middle East (Turkey: 2; Iran: 1), 2 in the African Nations (Ghana: 1; South Africa: 1), 1 in South Pacific (Fiji: 1), 5 in North America (United States: 5) and 1 in South America (Brazil: 1). Two studies were conducted across nations, with one study being conducted in five European nations (United Kingdom, Greece, Italy, Slovenia and Poland), and another being conducted in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Spain and Cameroon.

4. Discussion

In a review paper of studies related to coping strategies, it was concluded that a wide variety of different coping measurements and coping strategies have been reported, thereby highlighting the need for a standard coping system to categorize all the different coping strategies [9]. This conclusion may also be applied to coping among women IPV survivors, as other studies on coping strategies regarding IPV have revealed the wide variety of coping strategies used and the lack of a consistent system to define and categorize different coping strategies. As such, this study used the scoping review to review recent literature on IPV to examine the various coping strategies reported in the reviewed literature, as well as the various measurements used by researchers in the studies reviewed. This study also aims to investigate whether the various coping strategies reported in the studies reviewed could be categorized according to Skinner’s 11 families of coping.

For the first research question, our findings indicated that various coping strategies have been used by women IPV survivors and that different terminology has been used to label these coping strategies, which can be seen in Table 1 and Table 2. As prior research has noted [9], there has been a lack of clarity and consensus in defining categories of coping strategies. Our scoping review indicates that this comment also applies to the field of IPV. This lack of consensus in defining categories of coping strategies would lead to problems in understanding the coping strategies used by IPV, as it would be difficult to compare all the different studies to produce a complete picture of the coping strategies used by women IPV survivors. Accordingly, a classification system that can categorize all the different coping strategies is clearly needed.

Our second research question is to examine whether studies relating to the field of IPV used a variety of different coping measurements, as prior research commented that the lack of clarity and consensus in defining categories of coping strategies could be related to the use of different measurements [9]. Our scoping review found that different researchers tend to use different measurements and designs in studies of coping strategies among women IPV survivors. This scoping review found that the most common measurement was the use of qualitative interviews to collect data on the coping strategies used by women IPV survivors. However, different terms have been used to describe some similar coping strategies, such as positive cognitive processing versus positive thinking [16,22], distraction versus filling in time [10,16] and emotional regulation versus controlled expression of emotion [18,35]. Besides that, the results of this scoping review also reported five other different measurements that have been used by researchers to measure coping strategies in quantitative studies, such as the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE), the Cognitive Processing of Trauma Scale (POTS), the Intimate Partner Violence Strategies Index (IPVSI), and others, thus leading to different coping strategies being reported. Accordingly, a system that can categorize these similar coping strategies would be necessary to solve the clarity and consensus issues highlighted [9].

Our third research question examines whether Skinner’s 11 families of coping can address issues regarding clarity and consensus among coping strategies [10]. Two independent researchers matched the coping strategies from the reviewed studies to these 11 families and found that all strategies from the 27 studies fit within Skinner’s framework, demonstrating its applicability in IPV research. This study makes a significant methodological contribution by demonstrating the comprehensive applicability of the 11 families of coping to IPV research. While previous studies have noted the lack of consensus in classifying coping strategies [9], this study’s systematic categorization of all reported strategies across 27 studies proves Skinner’s framework’s unique value in resolving this issue. The following three key advances emerge: (1) the framework successfully integrates both qualitative and quantitative coping measurements under a unified system; (2) it reveals previously obscured patterns (e.g., support-seeking as nearly universal while problem-solving varies culturally); and (3) it enables direct comparisons across diverse cultural contexts where IPV occurs. This evidence establishes Skinner’s taxonomy as an essential tool for future IPV coping research, addressing critical theoretical and measurement challenges in the field.

Therefore, these 11 families of coping can be considered for use by other researchers in future studies of coping while analyzing their data, whereby researchers can choose to categorize the coping strategies based on the 11 families of coping in quantitative studies or develop a coping measurement that includes these 11 families of coping in quantitative studies, which will be useful in understanding and comparing the coping strategies used by women IPV survivors within different contexts. For example, by using these 11 families of coping, as shown in Table 2, we have found that the most commonly used coping strategies were support seeking (88.89%), with escape avoidance (55.56%) and problem-solving (44.4%) coming in at second and third. These findings indicate the importance of providing more resources for helping IPV survivors receive the social support that they need.

5. Conclusions

This study has revealed important findings regarding coping strategies among women IPV survivors, namely that there exists a wide variety of coping strategies used by women IPV survivors as well as a wide variety of coping measurements that lack a consensus and clarity in defining coping strategies. This is consistent with Nabbijohn et al. (2021)’s findings and highlights the issues that exist in research regarding coping strategies, especially in IPV studies [9]. This study has also provided support for the practicability of the use of Skinner et al.’s (2003) proposed 11 families of coping, which was able to categorize the wide variety of coping strategies that were reported in the 27 articles reviewed in this study [10].

6. Implications

In terms of theoretical implication, the findings of this study are in line with the transactional theory of stress and coping. Our scoping review indicates that women IPV survivors did use strategies to cope with the abusive threats they faced. Importantly, there is no certain strategy that is most appropriate or most effective, as women IPV survivors use a wide range of coping strategies to protect themselves based on their knowledge and experience of what actions will decrease the danger [7], and also the contextual factors of the situation the women were currently in [39].

One example of how IPV survivors decide what coping strategies will decrease the danger they are in is when the women change their coping strategies depending on whether their husbands are drunk [30]. If the husbands are drunk, the women resort to more aggressive coping strategies and change their coping strategies to being more submissive and placating when their husbands are not drunk. Another example is how women engaged in remarriage after leaving their abusive partners, as Turkish society considers divorced women as losing their status, and remarriage allows them to regain this status [17].

Accordingly, a coping theory that considers contextual factors should also be included in the transactional theory of stress and coping, which will be useful to explain why certain families of coping strategies are most likely to be used in certain contexts but not others and why certain families of coping strategies are most effective to reduce threats in certain contexts but not others. As suggested, fit and context are the most important components in determining the effectiveness of coping strategies [41].

As our scoping review suggests that the 11 families of coping can be used to categorize most of the coping strategies used by women IPV survivors, we suggest that these 11 families of coping can be integrated into the transactional theory of stress and coping to examine various context factors and outcomes linked to the adoption of these various coping strategies [8,10]. For example, in a culture where abuse is regarded as a disgrace, would women IPV survivors be less likely to use social support as a coping strategy and more likely to engage in helpless coping strategies?

In terms of practical contribution, this scoping review provided further backing that the 11 families of coping is a practical system for categorizing coping strategies in IPV studies [10]. Future studies may design a measurement to access these 11 families of coping for use in quantitative studies and may also use these 11 families of coping as a framework for use in qualitative studies. This helps to better organize and understand the various coping strategies used by women IPV survivors and facilitates the communication between qualitative and quantitative studies.

7. Limitations

Nonetheless, the interpretation of the results of this scoping review should be cautious. This scoping review was limited to the Scopus database and English articles; as such, articles in other languages that may be included in other databases may be overlooked. As such, future studies may consider including studies from various databases to further examine the validity of these findings. Besides that, while comparing the global and regional estimates of violence against women by the World Health Organization, with the countries of the current reviewed studies, more studies are needed in the Western Pacific and thus limit the generalization of current findings.

This scoping review chose to only include publications between the years 2017 and 2022. The decision to focus on articles published between 2017 and 2022 was based on several key considerations. First, this five-year timeframe ensured that the scoping review captured the most recent and relevant research available at the time the scoping review was conducted (which was in 2022), providing an up-to-date synthesis of contemporary knowledge in the field. A five-year span was also chosen to strike a balance between including novel research and allowing sufficient time for studies to undergo peer review and academic discussion, thereby enhancing their reliability. Given the extensive time and effort required for scoping reviews—including literature screening, data extraction, and synthesis—limiting the search to 2022 ensured feasibility while maintaining methodological rigor. While studies published after 2022 were not included, future research could expand this timeframe to incorporate newer findings. Additionally, based on the judgment of saturation, the researchers agreed that the final 27 articles are enough for analysis and to examine the RQ.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H.O. and P.C.S.; methodology, X.H.O., P.C.S. and Q.T.C.; validation, P.C.S. and W.Y.L.; formal analysis, X.H.O. and Q.T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H.O.; writing—review and editing, P.C.S., Q.T.C. and W.Y.L.; supervision, P.C.S., Q.T.C. and W.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| POTS | Cognitive Processing of Trauma Scale |

| IPVSI | Intimate Partner Violence Strategies Index |

| MARS | Measure of Affect Regulation Styles |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NGO | Non-governmental Organizations |

References

- Lövestad, S.; Löve, J.; Vaez, M.; Krantz, G. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Its Association with Symptoms of Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on a Female Population Sample in Sweden. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.K.; Zhang, X.; Basile, K.C.; Breiding, M.; Kresnow, M.J. Intimate Partner Violence and Health Conditions Among U.S Adults—National Intimate Partner Violence Survey, 2010–2012. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 38, NP237–NP261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Utz, A.; Mertens, L.J.; Renn, J.B.; Lucke, P.; Wöhlke, A.Z.; van Schie, C.C.; Mouthaan, J. Childhood Maltreatment, Borderline Personality Features, and Coping as Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 6693–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Cultural or Institutional? Contextual Effects on Domestic Violence Against Women in Rural China. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 36, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Bidmeshki, E.; Mohtashami, J.; Hosseini, M.; Saberi, S.M.; Nolan, F. Experience and Coping Strategies of Women Victims of Domestic Violence and Their Professional Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. Neuropsychiatr. Neuropsychol. 2021, 16, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, L.; Liu, B.C. Beaten Into Submissiveness? An Investigation into the Protective Strategies Used By Survivors of Domestic Abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping; Springer Publishing Company, Inc.: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nabbijohn, A.N.; Tomlinson, R.M.; Lee, S.; Morrongiello, B.A.; McMurtry, C.M. The Measurement and Conceptualization of Coping Responses in Pediatric Chronic Pain Populations: A Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 680277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Edge, K.; Altman, J.; Sherwood, H. Searching For the Structure of Coping: A Review and Critique of Category Systems for Classifying Ways of Coping. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 216–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and Weaknesses. FASEB Jl 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J.F. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Thelwall, M.; Orduna-Malea, E.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A Multidisciplinary Comparison of Coverage via Citations. Scientometrics 2020, 126, 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publ. 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, M.M.; Azman, A.; Singh, P.S.J.; Yahaya, M. A Qualitative Analysis of the Coping Strategies of Female Victimisation after Separation. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work. 2022, 7, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek-Küçükarslan, G.; Cankurtaran, Ö. Experiences of Divorced Women Subject to Domestic Violence in Turkey. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 2443–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffour, F.D.; Adomako, E.B.; Darkwa Baffour, P.; Henni, M. Coping Strategies Adopted by Migrant Female Head-Load Carriers who Experienced IPV. Vict. Offenders 2021, 17, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaptro, M.; Singh, S.P. Coping Strategies of Women Survivors of Domestic Violence Residing with an Abusive Partner after Registered Complaint with the Family Counseling Center at Alwar, India. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 48, 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Howell, K.H.; Sheddan, H.C.; Napier, T.R.; Shoemaker, H.L.; Miller-Graff, L.E. The Road to Resilience: Strength and Coping among Pregnant Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 8382–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, L.M.; Driessen, M.C.; Lewis-Dmello, A. An Evaluation of a Parent Group for Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N.; Michalska, P. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Processing in the Relationship Between Negative And Positive Effects of Trauma among Female Victims of Domestic Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP12898–NP12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboit, J.; de Mello Padoin, S.M. Driving Factors and Actions Taken by Women to Confront Violence: Qualitative Research Based on Art. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonsing, K.N.; Tonsing, J.C.; Orbuch, T. Domestic violence, social support, coping and depressive symptomatology among South Asian women in Hong Kong. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 26, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsing, J.; Barn, R. Help-Seeking Behaviors and Practices among Fijian Women Who Experience Domestic Violence: An Exploration of the Role of Religiosity as a Coping Strategy. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 64, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, K.A.; McCann, B.R. Violence and Abuse in Rural Older Women’s Lives: A Life Course Perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP2205–2227NP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzifotiou, S.; Andreadou, D. Domestic Violence during the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2021, 10, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akça, S.; Gençöz, F. The Experience of Disgust in Women Exposed to Domestic Violence in Turkey. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP14538–NP14563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, F.A.; Wahyudi, A.; Mujib, F. Resistance Strategies of Madurese Moslem Women against Domestic Violence in Rural Society. Al-Ihkam: J. Huk. Dan Pranata Sos. 2020, 15, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, C.; Suja, M.K. Through the Life of Their Spouses-Coping Strategies of Wives of Male Alcoholics. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 4442–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewuwo, O.B. Black Muslim Women’s Use of Spirituality and Religion as Domestic Violence Coping Strategies. J. Muslim Ment. Health 2020, 14, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewuwo-Gassikia, O.B. Black Muslim Women’s Domestic Violence Help-Seeking Strategies: Types, Motivations, and Outcomes. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2020, 29, 856–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisvianti, S.; Triastuti, E. Facebook Group Types and Posts: Indonesian Women Free Themselves from Domestic Violence. SEARCH J. Media Comm. Res. 2020, 12, 1–17. Available online: https://fslmjournals.taylors.edu.my/wp-content/uploads/SEARCH/SEARCH-2020-12-3/SEARCH-2020-P1-12-3.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Bhandari, S. Coping Strategies in the Face of Domestic Violence in India. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2019, 74, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Martínez, A.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; García-Zabala, M.; Páez-Rovira, D. “Mouth Wide Shut”: Strategies of Female Sex Workers for Coping with Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 3414–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muftić, L.R.; Hoppe, S.; Grubb, J.A. The Use of Help Seeking and Coping Strategies Among Bosnian Women in Domestic Violence Shelters. J. Gend.-Based Violence 2019, 3, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flasch, P.; Murray, C.E.; Crowe, A. Overcoming abuse: A Phenomenological Investigation of the Journey to Recovery from Past Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 3373–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; Hunt, S.; Milne-Skillman, K. ‘I Know It Was Every Week, But I Can’t Be Sure If It Was Every Day: Domestic Violence and Women With Learning Disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Vetere, A. “You Just Deal With It. You Have to When You’ve Got a Child”: A Narrative Analysis of Mothers’ Accounts of How They Coped, Both During an Abusive Relationship and After Leaving. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.; Ramon, S.; Vakalopoulou, A.; Videmsěk, P.; Meffan, C.; Roszczynska-Michta, J.; Rollé, L. Mental Health: Findings From a European Empowerment Project. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Drummond, S. Lazarus and Folkman’s Psychological Stress and Coping Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health; Cooper, C.L., Quick, C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).