1. Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), signed into law in 2010, represents one of the most ambitious and comprehensive healthcare reforms in U.S. history. Its main objectives were to expand access to health insurance, improve care quality, and reduce healthcare costs while addressing significant disparities in healthcare access and outcomes that disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities [

1,

2]. Prior to the ACA, Black and Hispanic/Latinx individuals had uninsured rates of 20.8% and 32.6%, respectively, compared with 11.7% for non-Hispanic Whites, contributing to reduced access to preventive care and worse health outcomes [

3,

4]. These disparities were further compounded by economic barriers, lack of employer-sponsored coverage, and higher poverty rates among minorities [

5]. One of the ACA’s central provisions was the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to individuals with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, which particularly benefited racial and ethnic minorities, as they are overrepresented among low-income and uninsured populations [

6,

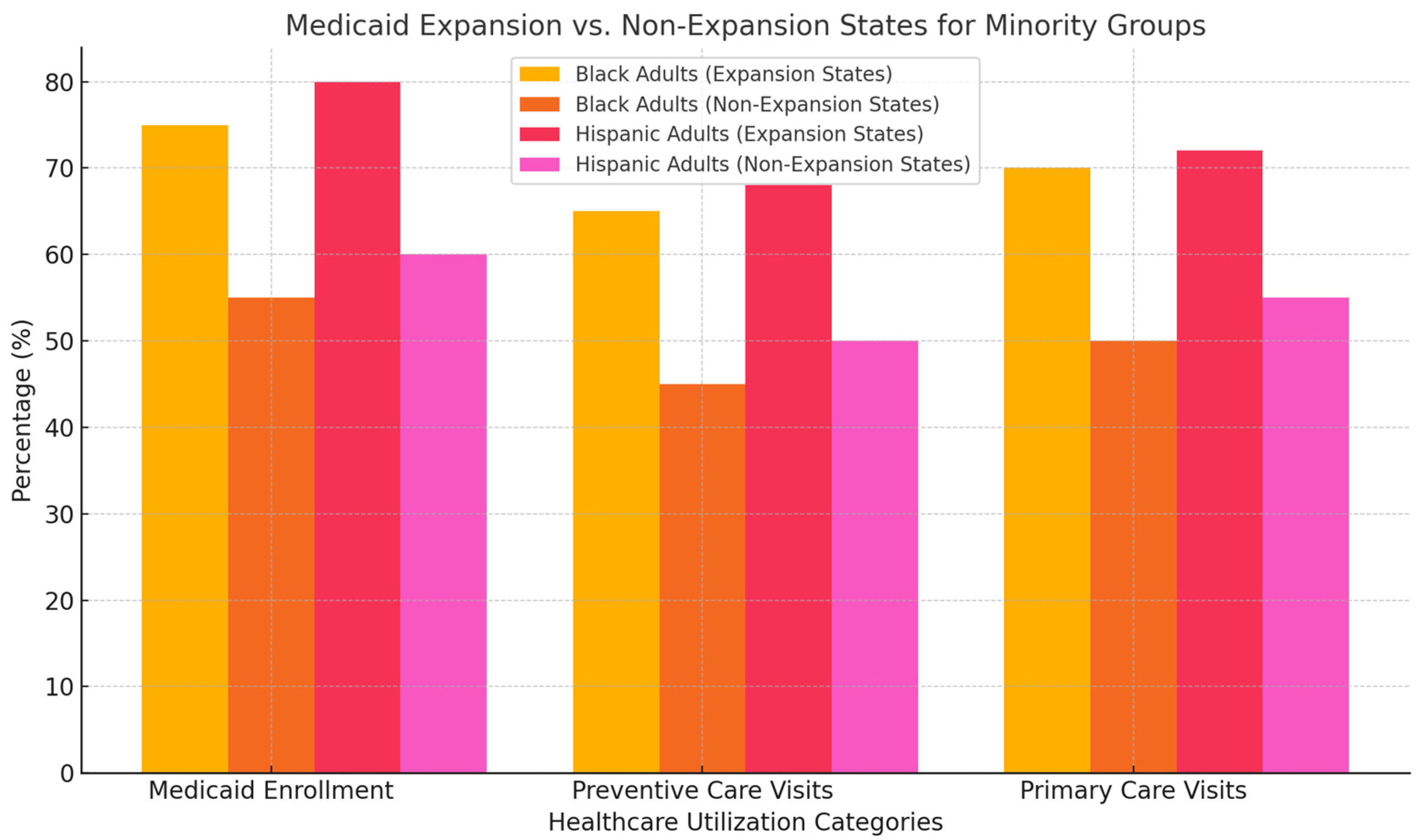

7]. This expansion led to significant improvements in coverage for minority groups, especially in states that adopted Medicaid expansion, where uninsured rates dropped by over 10 percentage points for Black and Hispanic adults [

8,

9]. However, disparities remain in non-expansion states, where many low-income minorities remain uninsured [

8].

In addition to Medicaid expansion, the ACA introduced health insurance marketplaces and provided subsidies to low- and middle-income individuals, which significantly expanded coverage options [

10]. The law also mandated that private insurance plans cover essential preventive services, such as cancer screenings, without cost-sharing [

7]. This provision was designed to address racial disparities in preventive care by removing financial barriers that had historically limited access for minority populations [

11]. Despite these gains, the ACA’s impact has been uneven, particularly in non-expansion states where many racial and ethnic minorities continue to face gaps in access to care [

6]. Recent studies have highlighted the ACA’s role in expanding coverage but have also drawn attention to persistent challenges, including affordability, geographic disparities, and systemic barriers such as linguistic and cultural obstacles [

2,

7]. Medicaid expansion states saw marked improvements in access to care and preventive services, including cancer screenings, vaccinations, and regular checkups, while non-expansion states experienced stagnation, exacerbating health disparities [

8,

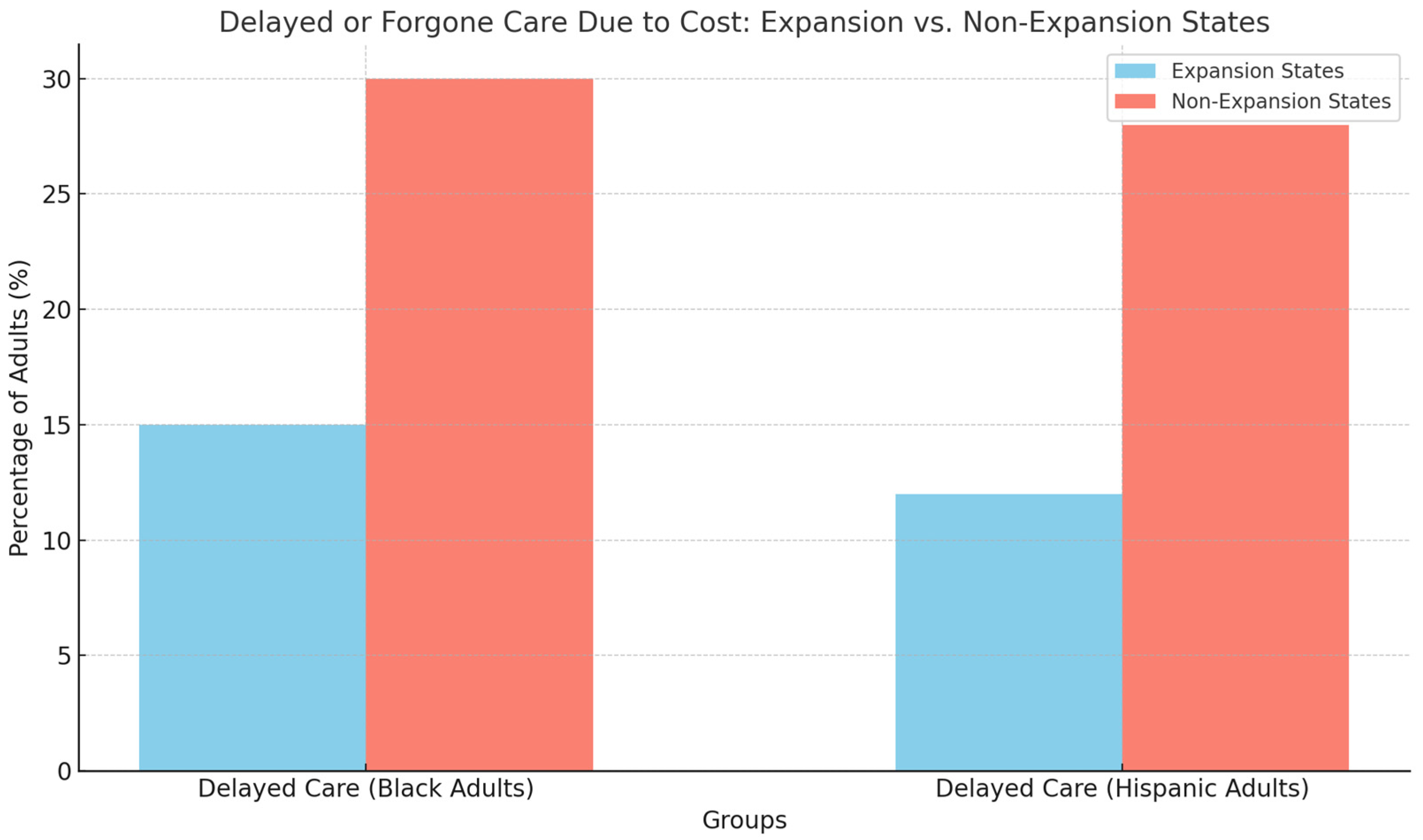

9]. For instance, Black and Hispanic adults in non-expansion states remain significantly more likely to delay care due to cost concerns [

6].

Furthermore, studies emphasize that the ACA’s insurance expansions did not fully address disparities in access to specialty care for minorities [

7]. Even in expansion states, minority populations still face barriers such as narrow provider networks, high out-of-pocket costs, and limited access to culturally competent care [

11]. These barriers have critical implications for the management of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, which disproportionately affect minority communities [

1]. This paper reviews the effects of the ACA on healthcare utilization among racial and ethnic minorities, focusing on insurance coverage, preventive services, and health outcomes. Through a synthesis of the existing literature, this review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the ACA’s role in reducing healthcare disparities and offer insights into the policy measures needed to further advance health equity.

While several studies and reviews have examined aspects of the ACA’s implementation, few have provided a focused synthesis of how the ACA affected healthcare utilization specifically among racial and ethnic minority populations. The existing literature often emphasizes changes in insurance coverage or health outcomes in the general population without critically examining heterogeneity by race, geography, or socioeconomic status [

10,

12,

13]. Moreover, most reviews have not systematically contrasted the experiences of minority groups in Medicaid expansion versus non-expansion states or addressed structural barriers such as provider network limitations, cost-sharing burdens, or culturally competent care. This paper contributes a novel perspective by integrating both empirical and policy-oriented evidence to assess the ACA’s uneven impacts on healthcare utilization across racial and ethnic groups. The review prioritizes quasi-experimental studies that offer stronger causal inference and considers how institutional settings and state-level policies shape outcomes for historically marginalized populations [

14,

15].

3. Selection of Relevant Literature

The literature reviewed in this paper was selected through a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed journals, policy reports, and government publications. A total of 52 studies were identified as directly relevant to the ACA’s impact on healthcare utilization among racial and ethnic minorities. The search focused on studies published between 2010, when the ACA was enacted, and 2023. The key databases utilized for the search included PubMed, JSTOR, and Google Scholar. In addition, key policy reports from institutions such as the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Urban Institute were reviewed to complement the academic literature with practical insights on the ACA’s implementation and effects [

6,

17].

The selection process prioritized studies that employed rigorous quasi-experimental methods, including difference-in-differences (DiD) methods, instrumental variable (IV) approaches, and regression discontinuity designs, as these methodologies provided robust evidence of causal relationships between ACA provisions and healthcare utilization outcomes [

9,

10]. These methods allowed researchers to isolate the effects of Medicaid expansion, the introduction of health insurance marketplaces, and other ACA provisions on healthcare coverage and utilization for minority populations. In total, 25 of the 52 studies included in this review utilized such rigorous econometric techniques, ensuring a high degree of reliability in the findings.

In addition to empirical studies, seven policy reports from the KFF, Urban Institute, and Commonwealth Fund were analyzed. These reports provided valuable context on the broader implementation of the ACA, particularly in terms of state-by-state variations in Medicaid expansion and the disproportionate effects of non-expansion on racial and ethnic minorities [

6,

17].

This review focuses on three major themes: the effects of the ACA on insurance coverage for racial and ethnic minorities, its impact on preventive healthcare utilization, and the persistent disparities in access and outcomes following implementation. Most empirical studies emphasized Medicaid expansion, which had the clearest and most immediate influence on access to care for low-income minority populations [

2,

8]. A smaller set of studies specifically examined non-expansion states, where many minority groups continued to face significant obstacles to affordable care [

3,

6].

To ensure both methodological rigor and policy relevance, the review incorporates a balanced mix of peer-reviewed empirical research and high-quality policy analyses from reputable institutions [

13,

15]. Studies that focused solely on financial outcomes, provider reimbursement rates, or broader macroeconomic factors were excluded, although their omission may limit understanding of how institutional or economic trends influence healthcare access. For instance, changes in hospital profitability or the structure of provider networks could indirectly affect care availability, especially in underserved or minority-dense communities. Similarly, some policy reports that did not stratify findings by race or ethnicity were excluded, even though they may have identified barriers with differential impacts. These areas warrant further exploration in future research to better understand the systemic determinants of equitable care delivery.

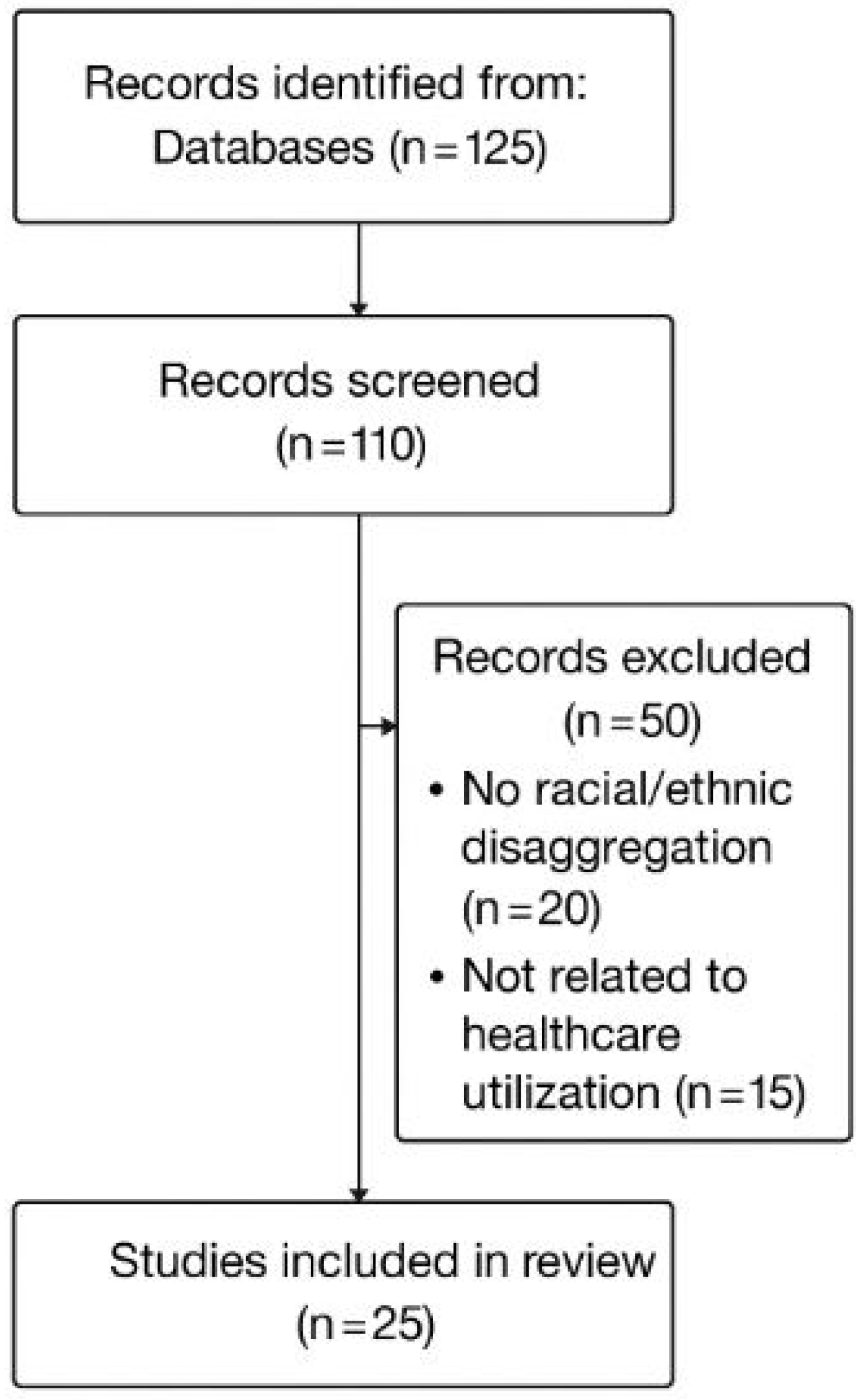

The systematic search used combinations of terms such as “Affordable Care Act” and “utilization” with modifiers like “racial,” “ethnic,” or “minority,” using both Medical Subject Headings (MeSHs) and free-text search strategies. The search initially identified 125 articles. After removing 15 duplicates, 110 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Full texts of 60 articles were then reviewed, and 35 were excluded—20 because they did not disaggregate results by race or ethnicity, and 15 because they did not examine healthcare utilization as an outcome. Ultimately, 25 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the sequential steps taken to select studies included in this review. Although this review employs a structured search and screening process inspired by PRISMA guidelines, it is not a systematic review in the formal sense. Specifically, this review does not include formal risk-of-bias assessments, study quality grading, or meta-analytic synthesis. Rather, it provides a narrative synthesis of the literature with an emphasis on causal methods and policy relevance.

Only studies conducted in the United States that explicitly addressed ACA-related reforms and disaggregated findings by race or ethnicity were eligible. Each study also needed to examine healthcare utilization as a primary or secondary outcome. Studies were excluded if they lacked such disaggregation or focused only on insurance coverage or self-reported health status without analyzing utilization behaviors.

Due to institutional access constraints, Scopus and Web of Science were not included in the search. PubMed was selected for its broad biomedical and public health indexing; JSTOR provided access to interdisciplinary research across health policy, economics, and sociology; and Google Scholar was used to capture grey literature and citations that might be missed in traditional databases.

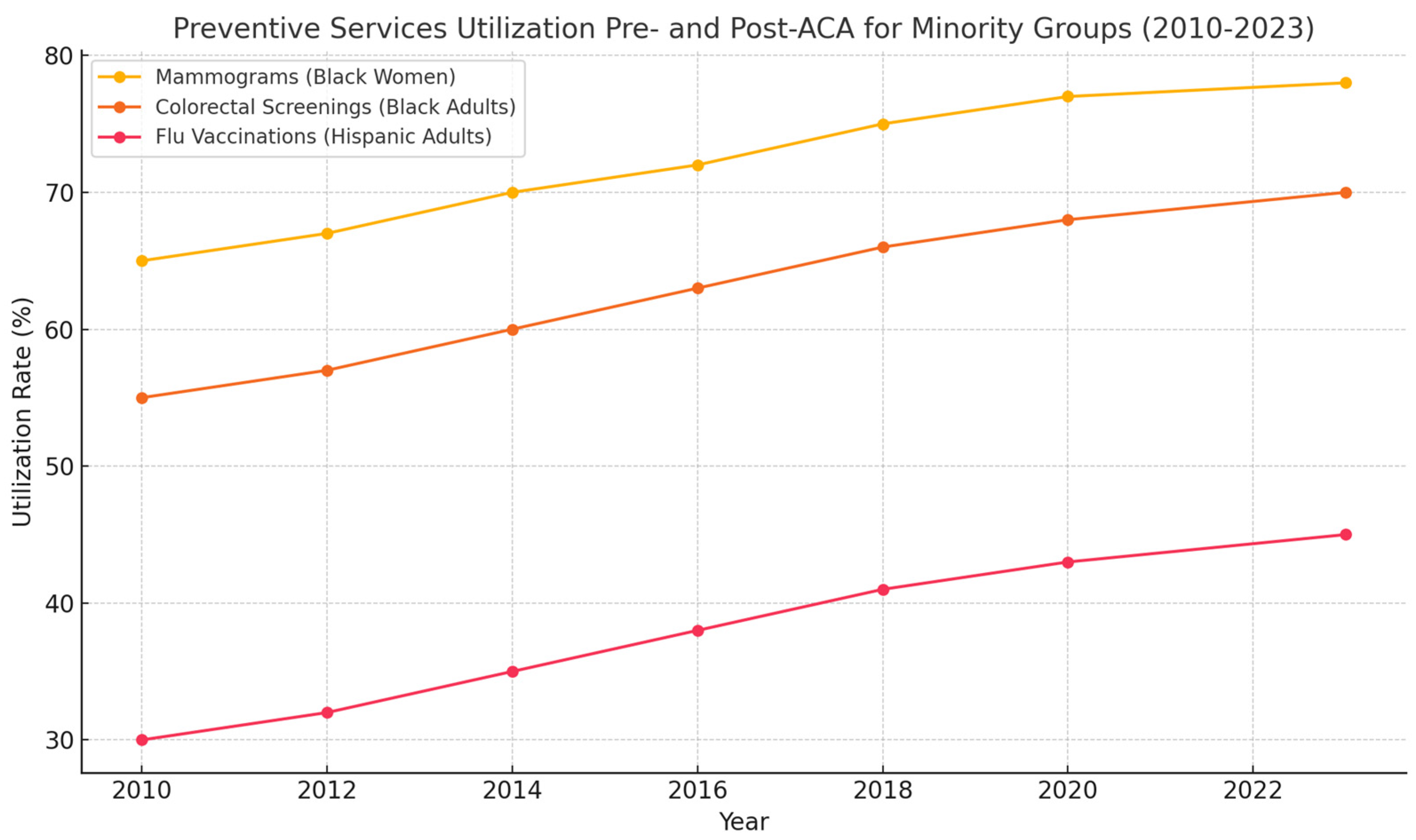

6. The ACA Effects on Health Outcomes

The ACA’s emphasis on preventive care contributed to marked improvements in health outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities, particularly in areas where early detection and management are critical. The increase in cancer screenings, for example, resulted in a reduction in the incidence of late-stage cancer diagnoses among Black and Hispanic populations. For instance, between 2010 and 2016, the incidence of late-stage breast cancer among Black women declined by 7%, largely attributed to the increased access to mammograms [

20]. Similarly, the rate of advanced-stage colorectal cancer diagnoses decreased for Hispanic adults as colorectal screenings became more accessible under the ACA [

7].

The ACA’s impact extended beyond cancer screenings. Improved access to regular check-ups, blood pressure monitoring, and cholesterol management helped reduce the prevalence of unmanaged hypertension and cardiovascular diseases among minority populations [

11]. Studies show that the rate of hospitalizations for preventable complications related to diabetes, heart disease, and stroke decreased among Medicaid enrollees, particularly in states that expanded Medicaid [

6].

In addition to chronic disease management, access to preventive care services also contributed to reductions in infant mortality rates among Black and Hispanic populations. The provision of prenatal care and regular check-ups under Medicaid expansion helped to close the gap in maternal and infant health outcomes, reducing disparities in preterm births and low birth weights for Black and Hispanic infants [

19]. These improvements highlight the significant role that preventive care plays in addressing long-standing health disparities.

While the ACA broadly expanded healthcare coverage and utilization, its effects were far from uniform across racial and ethnic groups, geographic locations, and institutional contexts. A more critical synthesis of the literature reveals meaningful differences in both the magnitude and mechanisms of the ACA’s impact. For example, Medicaid expansion led to a substantial reduction in the uninsured rate among Black adults and was associated with notable increases in primary care visits and preventive screenings such as mammograms and blood pressure checks [

10,

22]. In contrast, the effects for Hispanic adults, while positive, were more modest in many states, likely due to complex barriers including mixed immigration status within households, higher proportions of non-citizens, and structural exclusion from Medicaid eligibility [

9,

23]. This suggests that even universal reforms like Medicaid expansion can yield unequal gains depending on pre-existing legal and demographic contexts.

Furthermore, geographic variation played a critical role in moderating the ACA’s outcomes. Urban areas, which tend to have higher provider density and more robust health infrastructure, saw greater improvements in service utilization compared with rural areas, even when controlling for insurance gains [

7,

21]. In rural or underserved regions, particularly in non-expansion states, the lack of primary and specialty care providers often limited the actual translation of insurance coverage into meaningful healthcare access. This highlights that insurance expansion alone is insufficient if provider availability and health system capacity are not addressed concurrently.

Structural constraints also conditioned how specific ACA provisions affected racial and ethnic minorities. For instance, although the elimination of cost-sharing for preventive services under the ACA was associated with a general increase in screening utilization, studies show that the effect was significantly larger in counties with greater healthcare provider availability and lower rates of limited English proficiency [

1,

7]. In communities with persistent language barriers, low health literacy, or mistrust in healthcare institutions, the uptake of newly available services remained uneven, especially for immigrant populations. Therefore, the ACA’s success was contingent not only on insurance expansion but also on the broader social, cultural, and institutional environment in which individuals were embedded.

Taken together, these comparative insights emphasize the importance of contextualizing the ACA’s outcomes across multiple axes of inequality. Rather than viewing the ACA as a monolithic policy with uniform effects, the evidence points to a more complex reality in which race, geography, legal status, and system-level factors jointly shaped the law’s impact. Future policy reforms should not only expand coverage but also explicitly account for the intersecting barriers faced by disadvantaged communities in order to achieve equitable improvements in health utilization.

9. Conclusions

The ACA represents a significant step forward in addressing healthcare disparities and expanding access to health insurance for millions of Americans, particularly racial and ethnic minorities. Medicaid expansion and the elimination of cost-sharing for preventive services have played a central role in reducing uninsured rates and increasing healthcare utilization among minority populations [

1,

3]. However, the uneven adoption of Medicaid expansion, particularly in southern and non-expansion states, has left many racial and ethnic minorities without access to affordable healthcare, perpetuating disparities in health outcomes [

5,

7]. While the ACA has made important strides in improving healthcare access, significant challenges remain, particularly in non-expansion states where uninsured rates for Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults remain disproportionately high [

4,

6]. Additionally, affordability continues to be a barrier to care for many low-income individuals, and cultural and linguistic barriers further limit access to quality healthcare for non-English speaking populations [

9,

16].

Addressing these challenges will require targeted policy interventions, including the nationwide expansion of Medicaid, enhanced affordability measures, and investments in culturally competent care [

8,

19].

Future research should focus on understanding the long-term impact of the ACA on health outcomes for minority populations, as well as the role of non-expansion states in perpetuating healthcare disparities [

2,

5]. Additionally, research on the intersection of healthcare policy and social determinants of health is critical for informing future reforms aimed at reducing disparities and improving health outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities [

6,

7]. By addressing these challenges, policymakers can build on the progress made by the ACA and work toward achieving true health equity for all Americans. A key limitation of this review is that it does not meet the full methodological rigor of a formal systematic review. Risk-of-bias assessments, formal quality scoring, and quantitative synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis) were not conducted. As such, findings should be interpreted in the context of a structured narrative review rather than a systematic evidence appraisal. Future work may build upon this review using systematic methodologies to assess the quality and robustness of the included studies.

To contextualize findings within a broader policy evaluation framework, this review draws on the literature on policy design and capacity. As Howlett (2011) and Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (2015) argue, policy outcomes depend not only on the intended mechanisms but also on the capacities of the institutions, actors, and tools used in policy delivery [

24,

25]. The Affordable Care Act embodies a complex blend of design instruments—such as mandates, subsidies, and Medicaid expansion—that require multi-level implementation and coordination. Furthermore, Schneider and Ingram’s (1990) framework on social construction and target populations underscores how public perceptions and political narratives influence both policy design and differential uptake among marginalized communities [

23].

By integrating these perspectives, the review interprets racial and ethnic disparities in ACA outcomes as a function of both structural inequities and policy design challenges. Future efforts to advance health equity must consider not only insurance expansion but also the institutional, geographic, and cultural factors that condition healthcare access. A more intersectional and context-sensitive policy framework is essential to ensure that the gains from reforms like the ACA are equitably shared across all racial and ethnic communities.