Cultivating Well-Being: An Exploratory Analysis of the Integral Benefits of Urban Gardens in the Promotion of Active Ageing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

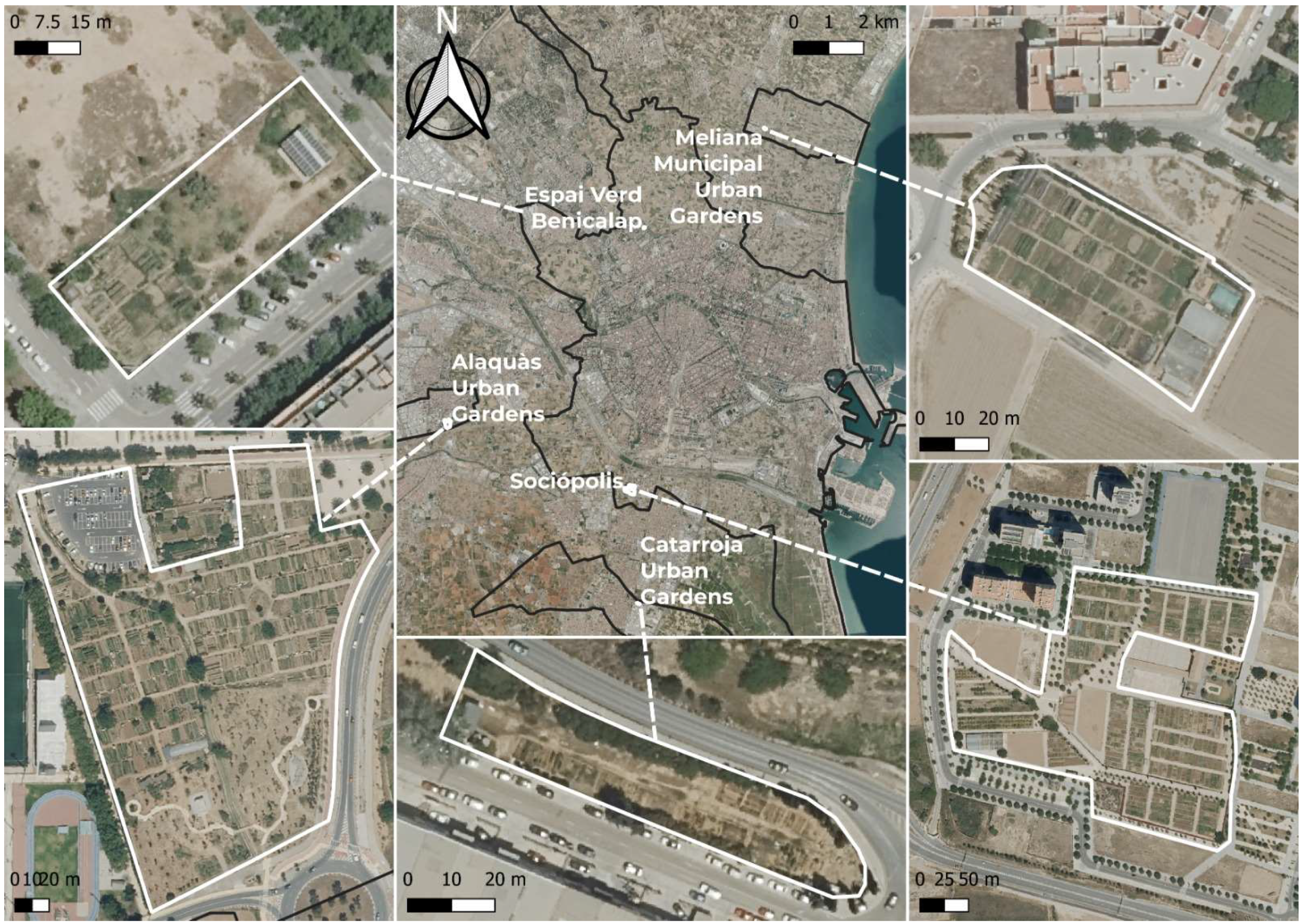

2.2. Spatial Context

2.3. Participants and Procedure

2.4. Guide to Interview Topics

2.5. Data Collection, Measures and Ethical Issues

3. Results

3.1. Behavioural Factors

3.1.1. Physical Activity

I3: “[When asked how they feel] Fine, very well, that’s the important thing about being in a garden.”

I9: “I’m not 18 yet, but I’m fine. Being in urban gardens, apart from creating a symbiosis with nature, you interact with your colleagues and socialise a lot. Very good.”

I10: “At the moment, physically I’m not doing well, but I relax here in the countryside, because at home there’s nothing to do and now I’m retired.”

I4: “Well, exhausted, but fine. I’m waiting for two operations, but I don’t want to have surgery […] One on my aorta and the other for a hernia …”

I7: “I feel perfectly fine. Apart from some heart problems and high blood pressure … but I’m fine.”

I13: “Lately I’ve been very worn out. My spine hurts a little and my legs hurt a lot. But I’m fine, I can cope and I’m getting myself motivated to come here [referring to the garden].”

I4: “Gardening, drinking beer, eating sandwiches …”

I5: “Yes, it’s more of a contemplative life than anything else. I also have a garden, but with trees. And then I also have animals and that keeps me entertained. I mean, more in the countryside than in the city, but let’s say both things go together.”

I6: “… I have two vices, gardening and fishing.”

I9: “Walking in the mornings, for example, taking my dog for a walk, I have a dog called Boira, and then when we get home I come to the urban gardens, because there’s always something to do there and I prefer to come every day.”

I12: “I go swimming at the weekends. The rest of the week I take my youngest grandson to school and then to the garden. […] I come here [to the garden] almost every day and now I’ve been pruning …”

I13: “My routine is the garden, I don’t have anything else to do, I plant a little, I keep myself busy with a few things, I go home, watch TV, and in the afternoon I come back here, walk around a bit, talk to people, and have a good time …”

I1: “Well, in the garden, I see that, for example, people who really like it and know how to do it can plant their own vegetables. Take the garden here, for example. This garden is run by [names someone] who is retired and knows a lot, so he takes good care of it and every morning he gets up and has something to do, which is to go down to his garden to see how the things he has planted are doing […] What do grandparents who have nothing to do do? They stay at home, have their coffee and then what? […] So this gives them a lot of life.”

I2: “Physically, it helps me not to hunch over, it loosens up my joints, it makes me feel good in my head […] and of course, I grow broccoli, leeks, strawberries, which I have now, so I eat quite well.”

I3: “Being here is a pleasure. There are days when you don’t feel like doing anything, but others, like today, when you say to yourself, “I need to do some exercise,” and you do it. So I think it’s perfect for people, especially at a certain age. For retirees, I think an urban garden is ideal.”

I5: “Well, I’m in very good physical and mental shape. Especially mentally. Because we have a good atmosphere here. […] It’s a very healthy, very relaxed atmosphere and it’s all for the best, to improve and to help people […] here we really do live together very well and everyone is happy and everyone tries to learn so that the vegetables and everything we plant and sow turns out well …”

I6: “The garden gives you a great sense of peace and well-being, we have a group, we have created an atmosphere and it gives you peace of mind and better health, happiness, happiness. Physically, I’m better, more relaxed, I’m not so lethargic. I don’t like television, so I come here or I go fishing.”

I7: “Exercising, having extraordinary colleagues … we’re actually celebrating our fifteenth anniversary. Two colleagues and I started it, and we’re very satisfied because today there are twenty of us and we have a great time. We have a goal, which is to have lunch together every day we can, and we’re doing very well.”

I11: “… I come here, I spend two or three hours here, even if I don’t have anything to do, because there’s always something to do if you want. […] It’s good for the plants, because plants have resources, because as soon as there’s no wind, they have roots to start growing, I mean, things like that. […] to keep you entertained for a while …”

I13: “Not wandering around … I get home and I sit down and my mind is racing, I think that’s the worst thing, and here I am talking to one person, then another, and now I’m going over there and there are two or three more friends of the same age […] If I were at home sitting around and my mind was racing, then my arms would be worse, my legs would be worse, my head would be worse, everything would be worse.”

3.1.2. Healthy Eating

I1: “… we eat a lot of fruit and vegetables at home. Lots of fruit and vegetables. I have a daughter, aged 26, who came home one day when she was 16 and said, ‘Mum, from now on I’m not eating meat. […] And then I had to get my act together and take a quick nutrition course and look for recipes that vegetarians could eat …”

I2: “… we eat a fairly varied diet at home, such as vegetables, rice, noodles, soups. […] and fruit, because now it’s orange season, there are two of us at home and we eat about 18 to 20 kilos of oranges every week.”

I6: “I have a lot of variety [referring to what he has planted in his garden], so I mainly eat vegetables and fish.”

I9: “… white meat, fish and, above all, vegetables, taking advantage of the fact that we have a plot of land, so there’s always something to eat.”

I10: “I eat everything, I don’t have any problems with food, meat, vegetables, anything you put in front of me. It’s true that I don’t like vegetables very much, but look what we have here [points to what he has planted in the garden] […] since I’ve been here, I eat more vegetables.”

I11: “Well, I especially eat a lot of variety. […] I buy a variety of all fruits. I almost always have almost all of them at home. […] We usually eat stews, which are called pucheros, with chard, vegetables, chickpeas, potatoes, because I really like stews.”

“Tomatoes are part of my daily diet. I eat legumes at least once a week, rice, pasta …”

I2: “… It’s not that I eat it, it’s that my children eat it and if there’s any left over, then a relative or an acquaintance will have some.”

I5: “Yes, yes, yes, we do everything here and most of it is organic, so of course, the taste of, for example, a carrot from here compared to a conventional one is a world of difference, the difference in taste and smell and everything […] the products here are obviously better than those in the supermarket, without a doubt, and then there are also the nutrients we add, which are also natural nutrients …”

I8: “Well, that’s one of my priorities [referring to eating the food he grows]. I try to go online and always make them in different ways and not just how we’re used to, for example, aubergines, which we only eat in one way, but you can eat them in many different ways, and I try to change […] I try to use everything we grow for our own consumption, to give to colleagues, for example, I have onions and I say: take four onions from there …”

I1: “I remember my father coming up with a basket full of tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers, and now when I’m given a tomato, I get that smell from my childhood. However, when I buy a kilo of tomatoes at the market, they don’t smell of anything, they’re like plastic …”

I6: “… well, yes, because I know what goes into the food I put on the table, I don’t add any hormones. Some people do …”

I8: “Yes, for the simple reason that I know what I’m eating. It’s 100% organic and the difference is, I don’t know if it’s because you grow it yourself, but it tastes better.”

I11: “Of course, my food is healthier, tastier, just look at the tomato plants here, look how beautiful they are, and compare those tomatoes with the ones you buy at the supermarket, they’re completely different, of course.”

I12: “In addition to the trend, which I already follow as part of a natural diet … when the lettuce and courgettes arrive, for example … you have to get the most out of them. […] They can be eaten puréed, grilled in slices …”

I1: “95% of what we eat comes from Morocco, where they use a lot of pesticides that are banned here […] if you look at the labels, it says “packaged in”, but they all come from either South Africa or Morocco.”

I3: “Oh, totally different [food from the garden and the supermarket]. You try to grow it with organic products, which is very important. Industrial products, large-scale, large-scale food production, don’t use those things because it’s more complicated […] if they’re organic, they’re very expensive and then who knows if they’re really organic. Here we know what we put into the product.”

I6: “Better, better. The best wealth is here, in the countryside, not in the city. And eating this food from here is 100 times better than what you get in the city. Normally, in the city, I buy things because, ecologically, I buy things, but … as little as possible, everything I can get from here I keep and have …”

I7: “In the city, you have to go shopping, and it’s not the same as eating something you’ve grown, raised and cared for yourself. What do you know about the things you buy? How long they’ve been there and how they’re going to be …”

I10: “Well, man, here we eat healthier than what they buy at the supermarket. For example, here when we have tomatoes in the summer, it’s heaven. […] Then in the summer we plant cucumbers and now, for example, I buy a cucumber from [names a supermarket] and it tastes like nothing. Now I have onions, I have beans, I have cauliflower, broccoli and lettuce, rosemary …”

3.2. Personal Factors

Psychological Well-Being

I1C: “Ah, I’m very well, I tell you, I took some time off because I was very, very stressed, because my job is very demanding and my body and my head were telling me that I had to stop, but now I’m great and my body is telling me to retire [I could have done so already] and devote myself to this, because the garden is filling my heart and soul …”

I2: “Yes, yes. And it also gives you a chance to socialise outside the garden, maybe go to the cinema or the bullring or the football. So a garden is very important.”

I5: “… I think being active here in the gardens also helps the mental well-being of the population, it gives you a sense of stability in terms of mental and physical health.”

I9: “This has many advantages […] it’s good vibes and psychologically very good. It frees you up a lot.”

E1: “And then, being in contact with nature, for example, I go to the vegetable garden and I might spend hours walking around the garden, and I can assure you that I come back with a totally different energy, it changes everything, it relaxes me. […] It’s work that you’ve done and then you get a reward for it and then you make yourself a salad and you say to yourself, look, I made this, this came from me. […] Well, if you’ve grown it yourself, I think that on an emotional level it’s very satisfying, it gives you pleasure. […] your mind is occupied and your body is too.”

I2: “For me, spending time in a vegetable garden is the greatest thing because when you’re in the garden, everything else you might have, well, you don’t have it anymore, it disappears […] it’s therapy.”

I3: “In everything, I think physically and then emotionally, and at home it’s great because you arrive and you have your space, you’re here, your wife has hers, and then you go home and you get together, and I think it’s very good for the relationship …”

I8: “Well, socialising is one of the most important things I give them, and you also get some exercise, and when you get tired you talk to one person, then another … and that gives people a zest for life, especially when they’re retired.”

I11: “For me, it’s what I was telling you. It takes my mind off everything I have outside and when I’m here I’m focused on the four floors. Before I had this, I was without it for a while after I retired … Of course, I used to walk two or three, four hours a day, which frees you up a bit, but this is better, it clears your mind, it’s like when you have children to look after.”

I12: “Psychologically, it means that … what would I do at home? If every time I come here I spend a couple of hours, at least, those two long hours multiplied by 80 visits, what would I do during those 80 visits at home? What would I do? I’d probably be in the way, but here I’m doing something useful, that is, I’m looking for a production, a material production, so to speak, and this is almost a production, let’s call it spiritual or at least social …”

3.3. Social Factors

3.3.1. Education

I1: “No, let’s see. I sign up for everything there is. […] For example, when they did this course on urban gardens here, I did come. […] I’ve learned a lot from the farmers here. […] Because they have, like my father, wisdom. Natural wisdom. […] They don’t teach you that at university.”

I3: “Well, they give courses here and what they explain is always interesting […] it’s always good. They give seminars from time to time, some courses, some talks… well, I think they’re interesting […] As for my colleagues, there are people who have much more experience because they’ve been doing it longer, and it’s always good to learn […] time makes you correct your mistakes. The first year goes by like everything else, you make mistakes, like you always have, but little by little you learn and the interesting thing is that last year I did this wrong and now I do it a little better …”

I5: “I’ve been evolving with all this my whole life. Especially when I was young, I adored my grandfather, and he taught me and told me […] I’ve been cultivating myself all my life, so you had to acquire knowledge through word of mouth […] so when you get together or when you get close to someone who has a lot or knows a lot or … then you always learn something, you always learn something.”

I7: “Well, I’ve read a book, specifically, which I’ve had for five years now, that talks about the whole subject of agriculture based mainly on the Mediterranean area. And it helped me a lot. But what has helped me the most is what I’ve learned here, because here there are people who really know.”

I9: “The training is … you try things out and you go along … as you talk to all your colleagues, some know more, so they explain things to you and you try them out too.”

I11: “Just through practice and also from the older people, it’s a chain. I remember when I was a child and I used to go with my father, and you learn from the older people about planting, the manure you use, the products … Of course, I know all that because I’ve learned it from the older people.”

I5: “For twelve years or so, even at university, I’ve always tried to teach people what I know, so I’ve tried to teach people so that they can learn about this [gardening] and do their own little things because I know it’s very relaxing and I’m delighted to be able to share my knowledge with others; that’s what I’ve lived for.”

I6: “People my age, if they came, yes, right away, if they committed themselves, yes, because here a lot of people think they can come and it’s like going to Mercadona, plants and the day after tomorrow you can pick them up, but here you have to be here every day …”

I7: “We’re already doing it, as much as we can, there’s no problem here, neither with the association members nor with outsiders. Lately, a lot of young people have joined, and we need them, and we’re here to help anyone who comes.”

I9: “Yes, of course, I became a grandfather two months ago, and I’m deciding that when she’s 4 or 5, I’ll bring her here, and I’d like to pass this on even more.”

I1: “Everyone here is retired now, and I promise you that when I talk to them, I notice that they are a wealth of wisdom. There are some who have hardly been to school, but they have a wisdom […] that they have acquired […] if young people want to learn, that’s good, because we are treating today’s youth very badly and they also have power, and there are many older people who have told me that they are willing to come with the kids [to the garden] to teach them and then let them continue on their own …”

I3: “Yes, the relationship is great [with the young people] and they also want to gain experience and you feel really good being able to teach something of your own to the young people who come.”

I6: “Well, we could give the young people experience and they could give us vitality …”

I7: “The relationship is built up over time and you help them with the little you know … in the long run, that’s what friendship is all about and it makes it more enjoyable for everyone to come.”

I8: “Well, look, intergenerational association is very important, and we have a school garden […] young people today have no idea. You ask them, “Where does this come from?” and they say, “From Mercadona” [supermarket]. That’s important.”

I9: “Above all, passing on experience and showing that there are people older than me who give you a sense of serenity and tranquillity, which is very commendable.”

3.3.2. Social Support

I2: “… I don’t go to the pub during the week, because if you go out, you come here to the garden, you walk around the garden, if you’re at home and a friend comes over or your children come over …”

I9: “… this is my main activity, I was also in the dance group […] Yes, my wife dances in the group and I used to sing in the group. Now, due to lack of time, I’ve given it up because I was a bit overwhelmed with too many things. […] Fortunately, I have many relationships …”

I12: “We usually get together once a month with colleagues from here [referring to the vegetable garden] in Alaquas. One colleague is also a teacher in Cuenca and another person [name of the person] is also from Cuenca, and we talk about things related to young people, such as food, military service, girlfriends, our lives … as if religion and politics didn’t exist.”

I13: “Mainly here [in the garden] and at half past five I go home and spend a little while there with her and then at half past five or six I leave and we go out for a walk. […] And at the weekends I go to the countryside, I’m in the countryside every weekend.”

I15: “Well, we get together with friends [in the garden], one tells a joke, another tells another, I tell another. And that’s the relationship I have, because now I was sitting with a friend who can hardly walk with [name of the person], and I feel sorry for the man. But then you get there and you spend some time with him and you talk and he tells a joke that I tell.”

I2: “Yes, of course, I do what I can and what I can’t do, I say, “hey, so-and-so, can you do this for me?”, and they do it […] for example, I can’t bend my back, but as there are several people watering, I say, “open it for me”, and they open it for me, and then I tell them I’ve had enough and they close it, and I’m grateful.”

I9: “It’s good for my health [the urban garden], I think, health, I don’t know, especially the interpersonal relationships between the “gentola”, between the good people around here, and I’m very comfortable, I’m very happy.”

I11: “Very good, as I said before, very good. Me and [names his friend from the next plot], it’s just what I’m telling you, there’s a relationship, I knew him from seeing him around here and I knew he was a teacher from the beginning, but now we know each other, well, several more things that I didn’t know about him and he didn’t know about me. […] There’s an incredible sense of solidarity here in the allotments, and we don’t lock up any of our small tools or anything. It’s incredible …”

3.4. Health Factors and Social Services

3.4.1. Health Promotion and Prevention of Physical and Mental Illness

I3: “Yes, yes, yes, yes, well, the physical improvement is very good, and also, when you come and spend two or three days doing physical exercise, you feel much better, you have more appetite, you sleep better, which is very pleasant.”

I5: “Well, there’s everything here, isn’t there? But generally, the people who are here are all well because they do what they think they should do. They don’t do any more or any less, no one is forced to do anything […] the atmosphere is cheerful, it doesn’t matter if you’re old or young, that’s how it is, it’s the atmosphere, healthy, calm, relaxed, where everyone communicates, we don’t care if you’re from Peru or China. Because here there are Chinese, Colombians, Argentinians. There are all races, colours and everything here. There are black people, white people, there’s everything here. Separate, separate… But here that’s not noticed, here that’s not categorised.”

I6: “Yes, I’ll say it again, instead of living a bad life in Valencia, sitting around […] well, look here. I haven’t stopped all morning, this afternoon I’m going back … […] Here, well, look, normally, from working with the machine, weeding, hoeing, sowing, you normally go with a hoe, scratching and removing weeds, you have a pretty good job within the limits of what’s available.”

I8: “We have a machine, a motorised hoe, but I like to do it the old-fashioned way, with a hoe. Why? Because as long as I can do it, I get exercise. If you think about it, you can do all the exercises you want here.”

I2: “Here I forget everything, I mean, I’m at work and if I have to make a ridge, I’m not thinking about the birds flying overhead, I’m focused on what I’m doing […] the countryside is wonderful, all the tasks are enjoyable, from the moment you start planting to seeing the plant grow and moving it around, checking for pests that could harm it, taking care of it because later that plant will give me a product and satisfaction when I eat it.”

I3: “Good, very good, it’s great for me [being in the garden] because I have a bit of tinnitus, so it’s perfect for me because there’s no noise here, which is very good […] And I’ve also shared this idea with some of my fellow gardeners and they also say that mentally and psychologically, they think it’s wonderful. I think it’s very good.”

I6: “I feel good about myself [in the garden]. When I come in here, it’s like when you go to work, you switch off, and when I come in here, I leave my problems behind.”

I11: “Mentally, the best thing, what it gives me most, is that until I leave here, my mind is focused on the four plants. If you tell someone that you can spend 4–5 h here every day […] it’s simply that you find a way to pass the time doing little things, of course.”

I12: “Well, here you can switch off if you have something on your mind and you arrive and say, “What do I have to do today?” Well, today I have to start removing this, or I’ll go and see if the beans have sprouted, or I’ll go and sulphate the cabbages so they don’t rot…”

3.4.2. Long-Term Care

I1: “Sure, it improves [mental health problems]. I know people who suffer from depression, especially mental illness, and I know people who have been cured by going to the garden. Little by little, I think, as I said, nature works miracles …”

I5: “This enriches the soul, the body, the mind, it enriches everything. You come here lame and you leave running.”

I6: “… if a person is at home sitting down and not moving, logically they have more disabilities than someone who comes here and works. For example, next to 100 [plot number], there is a very old man, an elderly man, who walks with a stick, and you have him there working every day. That person won’t get depressed or lethargic because of that, because he’s active …”

I7: “For me, apart from what the fields are, I consider this a health centre and that everyone should consider coming and having the opportunity to enjoy this option that we have, which years ago we couldn’t even dream of having.”

I9: “Yes, for example, if it can help a person not to be dependent. To be more agile. In fact, the guys from [names an association] with functional diversity, at a certain point they may find that by coming here you set guidelines, there is an improvement in mood.”

3.5. Purpose in Life

Retirement

I6: “Well, I retired a year early because I had colon surgery, and the only thing I’ve felt is that I’ve retired and started seeing doctors […] this activity has also helped me fill the time.”

I8: “Well, when I retired, I found that I had to find ways to keep myself busy. It’s a bit of a sudden change, because you have routines and then you have to change them, and now I have to come here in the mornings and do things …”

I10: “… A person has to retire and retire, I’ve felt fine, I haven’t had any problems, I haven’t had any stress or anything like that […] this [having the garden], well, first I came to help a lady who my wife used to look after and her husband died and she had a plot there and she got me involved without meaning to and then I went to the town hall and applied.”

I3: “Afterwards, shortly after [retiring], I quickly realised that I liked it.”

I5: “Yes, this is investing in your health when you’re older.”

I7: “… as soon as I found out about this in the newspaper, I went to the council and they gave me the application form, I filled it in and when I had the chance I joined. For me, this has been incredibly positive.”

I9: “Yes, 100% [it takes up the time I used to spend at work, in the garden].”

I11: “I often come here, maybe I bring a banana or something, and there are several others who come here for lunch too, and you chat for a while and clear your head, you know […] that’s what I mean, spending two or three hours, even if you don’t have to do anything.”

3.6. Physical Environmental Factors

Clean Air

I1: “Well, sometimes yes, sometimes no, because it’s what I’m telling you. For example, sometimes I put my hand up because when they’re spraying the air, I can feel it’s polluted and you can smell it a lot. […] Well, imagine that all this is stuck to the fruit in the supermarkets and we’re eating it […] and then, when it’s more or less normal [without the smell of sulphur], well, you do notice that, of course, there are a lot of trees, a lot of green, a lot of this and that, so it’s much better than in the city.”

I5: “… The air here is polluted, well, here in Valencia and in all the big cities. In all the ones I’ve been to, the pollution is terrible. So I’ve bought some land outside the city, 60 kilometres away, in Albaida, where I have fruit trees, animals and everything. Otherwise, this place stresses me out, the oxygen here stresses me out a lot, it makes me nervous, it makes me neurotic. And when I’m there, I sleep really well, I feel great, I mean, you can tell in everything, I feel it in my body, in everything …”

I9: “100% or 1000%. It’s true that we’re still close to the town, but even so, the air is wonderful.”

I12: “Here where we are, yes. Because even though we’re a stone’s throw from Valencia, we’re surrounded by trees on the right and trees on the left and some amazing green areas. […] So the air I breathe is healthy.”

I14: “Well, no, because there’s a lot of traffic. If you go out on the street, there’s a lot of traffic, a lot of smoke. If you go to a shop [names different supermarkets], you can’t breathe properly either. You have to go out to the countryside to be able to breathe properly. I mean, you breathe better in the garden or in the countryside.”

I15: “That’s not true. No, everything is polluted, and it’s getting worse every day. If we look at all the old cars that pollute and the planes that pollute, it’s outrageous, and everything is polluted. Even the sea is polluted, the boats, so everything is polluted […] because the planet is in a very bad way … the thing is, we don’t realise it, especially older people, but young people are studying and know more about what’s going on.”

I2: “I feel different [when I’m in the garden] because I come with the excitement of doing a job, I do it, and when I leave, I look at it and look at it again. It’s personal satisfaction.”

I3: “Well, as I said, the fresh air, let’s say, the contact with people. I also like the city, of course, I like sharing and having friends, going out with them …”

I6: “Well, the city is very … I don’t like it very much. Just yesterday we went to the centre and, to be honest, I felt overwhelmed […] No, I don’t like it. I prefer peace and quiet.”

I7: “Well, I would stay here [in the garden], yes.”

I8: “It’s very difficult to explain. Here today it feels like you’re in a more proper environment [in the garden]. When you’re in the city, you see all the pollution, which also reaches here, and that makes me feel uncomfortable. I’ve realised that the older I get, the less I can stand crowds; I look for peace and quiet.”

I14: “Well, you notice the change between being outdoors and being in the city, or in the village, wherever you live, of course you notice it.”

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harper, S. How Population Change Will Transform Our World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, V.; Arribas, J. Principales cambios demográficos mundiales y sus consecuencias. Gac. Sindr. Refl. Debate 2022, 39, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Population Structure and Ageing. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Population and Population Change Statistics. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_and_population_change_statistics (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Marzetti, E.; Lattanzio, F.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.; Onder, G.; Joint Action ADVANTAGE WP4 Group. Frailty multimorbidity: A systematic review meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales (IMSERSO). Ageing in Spain: Report 2020; IMSERSO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/imserso-ageingspain-01.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). Envejecimiento Activo: Un Marco Político; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/Envejecimiento_Activo_2015_es.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe—Statistics on Population Developments. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Population Projections at Regional Level. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_projections_at_regional_level (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Mortality and Life Expectancy Statistics. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Mortality_and_life_expectancy_statistics (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe—Statistics on Health and Disability. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxemburg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_health_and_disability (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. España: Perfil Sanitario Nacional 2023; State of Health in the EU; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-12/2023_chp_es_spanish_0.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Calvo, C.B.; Guerra, J.A.I.; Andrés, M.I.G.; Abella, V. Dependencia y edadismo. Implicaciones para el cuidado. Rev. Enferm. CyL 2009, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.J.; Martínez-Velilla, N.; Vidán, M.T.; García-Navarro, J.A. COVID-19, adulto mayor y edadismo: Errores que nunca han de volver a ocurrir. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 55, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Román, M. Edadismo y Autoimagen entre las Personas Mayores en España: Una Aproximación Cualitativa Desde la Perspectiva de Género. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baltar, A.L. Edadismo: Consecuencias de los estereotipos, del prejuicio y la discriminación en la atención a las personas mayores. Algunas pautas para la intervención. Inf. Portal Mayores 2004, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Badillo, T.; Miranda-Posadas, C.; Cruz-Barrera, L.G.; Martínez-Aguilar, M.; Gutiérrez-Sánchez, G.; Aguilar-Hernández, R.M. Estereotipos negativos sobre la vejez en estudiantes universitarios de enfermería. Rev. Enferm. Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2016, 24, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, L.; Walker, A. Active and successful aging: A European policy perspective. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendizábal, M.R.L. Envejecimiento activo: Un cambio de paradigma sobre el envejecimiento y la vejez. Aula Abierta 2018, 47, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilov, I.; Atzeni, M.; Perra, A.; Moro, D.; Carta, M.G. Active aging and elderly’s quality of life: Comparing the impact on literature of projects funded by the European Union and USA. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantzi-Vicente, S. El Envejecimiento Activo y Saludable: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica del ámbito social. Res. Ageing Soc. Policy 2024, 12, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Decenio del Envejecimiento Saludable 2021–2030; Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/es/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Pérez de Arenaza Escribano, C. Qualitative Research on Diagnoses and Plans of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Global View of the Spanish Network; Executive Report; Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales (Imserso): Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://imserso.es/documents/20123/0/informe_estudio_ccaa_infoeje_ingles_20240405.pdf/36248a81-d9da-a3c1-b5fe-c55bf16c2113 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Rémillard-Boilard, S.; Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Developing Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Eleven Case Studies from around the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hoof, J.; Marston, H.R. Age-friendly cities and communities: State of the art and future perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alley, D.; Liebig, P.; Pynoos, J.; Banerjee, T.; Choi, I.H. Creating elder-friendly communities: Preparations for an aging society. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2007, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, K.G.; Caro, F.G. An overview of age-friendly cities and communities around the world. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2014, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, R.; Townshend, T. Avoiding ‘bungalow legs’: Active ageing and the built environment. J. Urban Des. 2025, 30, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Nordin, N.A.; Aini, A.M. Urban green space and subjective well-being of older people: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Chen, M. A systematic review of measurement tools and senior engagement in urban nature: Health benefits and behavioral patterns analysis. Health Place 2025, 91, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Backx, K.; Clayton, D.A. Allotment gardening and other leisure activities for stress reduction and healthy aging. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejías Moreno, A.I. Contribución de los huertos urbanos a la salud. Hábitat Soc. 2013, 6, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharrey, M.; Darmon, N. Urban collective garden participation and health: A systematic literature review of potential benefits for free-living adults. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 80, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Mercer, J.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Clayton, D.A. “Doing” gardening and “being” at the allotment site: Exploring the benefits of allotment gardening for stress reduction and healthy aging. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detweiler, M.B.; Sharma, T.; Detweiler, J.G.; Murphy, P.F.; Lane, S.; Carman, J.; Chudhary, A.S.; Halling, M.H.; Kim, K.Y. What is the evidence to support the use of therapeutic gardens for the elderly? Psychiatry Investig. 2012, 9, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.-H.; Shin, S.; Son, Y.-G.; An, B.-C. Seniors’ participation in gardening improves nature relatedness, psychological well-being, and pro-environmental behavioral intentions. J. People Plants Environ. 2022, 25, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yanai, S.; Xu, G. Community gardens and psychological well-being among older people in elderly housing with care services: The role of the social environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 94, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyg, P.M.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C.J. Community gardens and wellbeing amongst vulnerable populations: A thematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 35, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutter, C.; Stoltz, A. Community gardens and urban agriculture: Healthy environment/healthy citizens. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Albert, C.; von Haaren, C. The elderly in green spaces: Exploring requirements and preferences concerning nature-based recreation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. The urban gardens in South Tyrol (IT): Spatial distribution and some considerations about their role on mitigating the effects of ageing and urbanization. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 7, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Bravo, L.; Torruco-García, U.; Martínez-Hernández, M.; Varela-Ruiz, M. La entrevista, recurso flexible y dinámico. Investig. Educ. Méd. 2013, 2, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucre González, L.; Cedeño González, J.A. Una mirada distintiva a la tendencia investigativa cualitativa: Interaccionismo simbólico. Atlante Cuad. Educ. Desarro. 2019, 105, 10–76. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Valencia/València: Población por Municipios y sexo. Cifras Oficiales de Población Resultantes de la Revisión del Padrón Municipal a 1 de Enero de 2023. INE: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=2903 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Población por Sexo, Municipios y Edad (Grupos Quinquenales). Estadística del Padrón Continuo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=33944 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Mwita, K. Factors influencing data saturation in qualitative studies. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Saturation: An overworked and misunderstood concept? Qual. Inq. 2024, 30, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, S.; Afni, M. Best Practices of Semi-Structured Interview Method; Chittagong Port Authority: Chittagong, Bangladés, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting semi-structured interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 4th ed.; Newcomer, K.E., Hatry, H.P., Wholey, J.S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, T.L.; Masser, B.M.; Pachana, N.A. Exploring the health and wellbeing benefits of gardening for older adults. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 2176–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, J.S.; Alaimo, K.; Harrall, K.K.; Hamman, R.F.; Hébert, J.R.; Hurley, T.G.; Leiferman, J.A.; Li, K.; Villalobos, A.; Coringrato, E.; et al. Effects of a community gardening intervention on diet, physical activity, and anthropometry outcomes in the USA (CAPS): An observer-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e23–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.; Tracey, D.; Truong, S.; Ward, K. Community gardens as local learning environments in social housing contexts: Participant perceptions of enhanced wellbeing and community connection. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.T.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Germani, A.C.C.G.; Bógus, C.M. The impact of urban gardens on adequate and healthy food: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palar, K.; Hufstedler, E.L.; Hernandez, K.; Chang, A.; Ferguson, L.; Lozano, R.; Weiser, S.D. Nutrition and health improvements after participation in an urban home garden program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | Garden Name | Gender | Educational Level | Professional Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Espai verd | Female | Higher education | Commercial |

| I2 | Meliana | Male | Primary education | Automotive trade |

| I3 | Sociópolis | Male | Secondary education | Telecommunications |

| I4 | Sociópolis | Male | Secondary education | Telecom and environmental services |

| I5 | Sociópolis | Male | Primary education | Food production |

| I6 | Sociópolis | Male | Primary education | Transport and maintenance |

| I7 | Sociópolis | Male | Secondary education | Commercial |

| I8 | Sociópolis | Male | Higher education | Administrative (automotive) |

| I9 | Alacuás | Male | Primary education | Livestock and transport |

| I10 | Alacuás | Male | Primary education | Construction |

| I11 | Alacuás | Male | Primary education | Passenger transport |

| I12 | Alacuás | Male | Higher education | Teacher |

| I13 | Alacuás | Male | Primary education | Construction |

| I14 | Catarroja | Female | Higher education | Healthcare support |

| I15 | Catarroja | Male | Primary education | Construction |

| Dimension | Main Category | Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioural factors | Physical activity | -Positive perception of physical condition linked to active and continuous participation in the urban garden. -Reduction in sedentary lifestyles during retirement. -Adapted and accessible physical activity. -Stimulation of joint mobility, combating stiffness and improving muscle tone. -Preference for traditional gardens as a setting for physical activity (high sense of biophilia). |

| Healthy eating | -Improved dietary patterns. -Transformation of food preferences. -Regular consumption of home-grown food. -Perception of higher quality of food compared to that sold in supermarkets. -Greater confidence in the food consumed thanks to knowledge of its origin and cultivation process (evaluation of taste, freshness, smell and safety of products). -Evocation of childhood memories after consuming products grown in the garden. -Greater satisfaction when eating. -Concern for local consumption. -Food vegetable self-sufficiency. -Pleasant gastronomic experience. -Source of healthy and satisfying nutrition. -Distrust of industrialised or organic products sold in supermarkets. | |

| Personal factors | Psychological well-being | -Routine activity. -Emotional support space (promoting resilience, autonomy and psychological balance) -Personal and emotional satisfaction from growing food. -Strengthening social ties with people in the garden, replacing the social void left by retirement. |

| Social factors | Education | -Acquisition of knowledge through cultivation practices. -Transmission of family knowledge (respect for traditional knowledge) -Intergenerational learning (two-way teaching-learning process) -Collaborative learning among users. -Opportunity to share agricultural knowledge and gain personal recognition. -Support for new gardeners -Daily exchange of knowledge among peers. |

| Social support | -Main meeting and social space -Building meaningful relationships between users. -Reducing unwanted loneliness. -Building mutual support networks. -Developing values: empathy and solidarity. | |

| Health factors and social services | Health promotion and prevention of physical and mental illness | -Increased daily vitality. -Improved mood, appetite and sleep quality. -Gardening as a valuable alternative to limited space or a replacement for more rigid or unhealthy leisure and free time activities. -Multicultural environment (promoting cultural exchange, reducing prejudice and stereotypes, and fostering social cohesion and the inclusion of at-risk groups). -An environment for disconnecting, finding peace and concentration (performing consecutive tasks: planting, sowing, watering, cultivating, weeding, pruning, harvesting). |

| Long-term care | -Reduced risk of dependency or disability (promotion of physical activity). -Therapeutic value with improved mood. -Promotion of mental stimulation. | |

| Purpose in life | Retirement | -New purpose in life after retirement. -Urban gardening as a tool for continuing physical and social activity. -Strategy for spending time in a meaningful and active way. |

| Physical environmental factors | Clean air | -Ambivalent perception of air quality. -Context of widespread pollution (urban garden) -Space for calm, relaxation and personal satisfaction, contrasting with the stress, pollution and ‘commotion’ associated with the city. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Salido, N.; Gallego-Valadés, A.; Serra-Castells, C.; Garcés-Ferrer, J. Cultivating Well-Being: An Exploratory Analysis of the Integral Benefits of Urban Gardens in the Promotion of Active Ageing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071058

Fernández-Salido N, Gallego-Valadés A, Serra-Castells C, Garcés-Ferrer J. Cultivating Well-Being: An Exploratory Analysis of the Integral Benefits of Urban Gardens in the Promotion of Active Ageing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071058

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Salido, Noelia, Alfonso Gallego-Valadés, Carlos Serra-Castells, and Jorge Garcés-Ferrer. 2025. "Cultivating Well-Being: An Exploratory Analysis of the Integral Benefits of Urban Gardens in the Promotion of Active Ageing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071058

APA StyleFernández-Salido, N., Gallego-Valadés, A., Serra-Castells, C., & Garcés-Ferrer, J. (2025). Cultivating Well-Being: An Exploratory Analysis of the Integral Benefits of Urban Gardens in the Promotion of Active Ageing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071058