Unveiling the Impact: A Scoping Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Racialized Populations in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

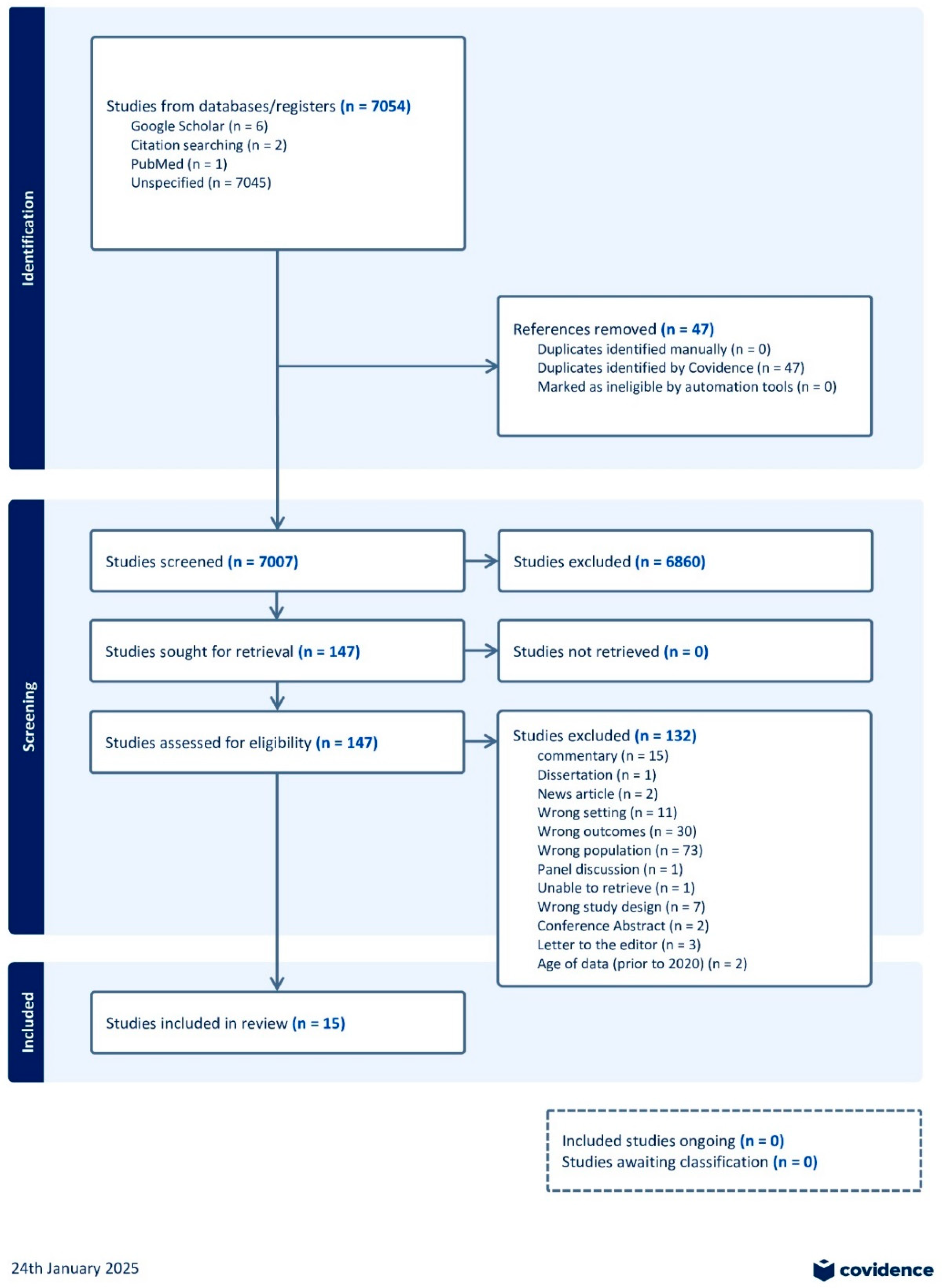

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence and Data Extraction

2.5. Synthesis of Results

2.6. Synthesis

2.7. High COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality Rates

2.8. Increasing Discrimination During COVID-19

2.9. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health

2.10. Difficulty in Accessing Healthcare

2.11. Impact on the SDoH

2.12. The Childcare Dilemma and Unemployment Struggles

2.13. Challenges with Accessing Food

2.14. Coping with Challenges with Accessing Food

2.15. Feelings of Loneliness and Impact on Social Networks

2.16. Economic Impacts

2.17. Essential Workers and Job-Nature-Related Impacts

3. Discussion

4. Future Recommendations

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Peer-Reviewed Articles’ Search Strategy

- 1 exp pneumonia, viral/or exp coronavirus infections/

- 2 exp Racial Groups/

- 3 exp “American Indian or Alaska Native”/

- 4 exp Indians, North American/

- 5 middle eastern canadians.mp.

- 6 exp “Health Disparate, Minority and Vulnerable Populations”/

- 7 exp social problems/or exp socioeconomic factors/

- CINAHL (Ebsco platform)

- S79 S76 AND S77

- S78 S76 AND S77

- S77 S28 OR S49 OR S67

- S76 S13 AND S75

- S75 S69 OR S70 OR S71 OR S72 OR S73 OR S74

- S74 SO (canada or canadian* or “british columbia” or “colombie brittanique” or saskatchewan or manitoba or ontario or quebec or “new brunswick” or “nouveau brunswick” or “nova scotia” or “nouvelle ecosse” or “prince edward island” or “ile du prince edouard” or newfoundland or “terre neuve” or labrador or nunavut or nwt or “territoires du nord ouest” or “northwest territor*” or yukon or “north america” or toronto or montreal or vancouver or ottawa” or edmonton or “quebec city” or winnipeg or hamilton…

- S73 (canada or canadian* or “british columbia” or “colombie brittanique” or saskatchewan or manitoba or ontario or quebec or “new brunswick” or “nouveau brunswick” or “nova scotia” or “nouvelle ecosse” or “prince edward island” or “ile du prince edouard” or newfoundland or “terre neuve” or labrador or nunavut or nwt or “territoires du nord ouest” or “northwest territor*” or yukon or “north america*” or toronto or montreal or calgary or ottawa or edmonton or winnipeg or vancouver or gatineau or “queb…

- S72 (canada or canadian* or alberta or “british columbia” or “colombie brittanique” or saskatchewan or manitoba or ontario or quebec or “new brunswick” or “nouveau brunswick” or “nova scotia” or “nouvelle ecosse” or “prince edward island” or “ile du prince edouard” or newfoundland or “terre neuve” or labrador or nun?v?t or nwt or “territoires du nord ouest” or yukon)”

- S71 (MH “Aboriginal Canadians+”)

- S70 (MH “North America+”)

- S69 (MH “Canada+”)

- S68 S29 AND S49

- S67 S64 OR S65 OR S66

- S66 (MM “Intersectionality”)

- S65 S53 AND S62

- S64 S53 AND S62

- S63 s53 NOT s59

- S62 S60 OR S61

- S61 “work outside the home”

- S60 “work onsite”

- S59 S54 OR S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58

- S58 “shelter at home”

- S57 (MM “Telecommuting”)

- S56 “work at home”

- S55 “work from home”

- S54 “work remotely”

- S53 S50 OR S51 OR S52

- S52 TX (trustee* or astronaut* or ethicist* or “foreign professional personnel” or “government employee*” or “ metal worker*” or miner* or police or monk* or nun* or “firefighter* or “sex worker*”)

- S51 (MM “Case Managers”) OR (MM “Correctional Facilities Personnel”) OR (MM “Doulas”) OR (MM “Farmworkers”) OR (MH “Military Personnel+”) OR (MM “Pilots”) OR (MM “Blue Collar Workers”)

- S50 TX “essential worker*”

- S49 S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48

- S48 TX (“economic disparit*” or “structural inequality” or “food insecurity” or deficienc* or “lack of social security” or unemploy* or welfare or intersectionality or “health inequity” or “health inequality”)

- S47 TX (homeless or “loss or dwelling” or unsheltered or “lack of shelter” or “in need of housing” or “housing deprived”)

- S46 “sociology problems”

- S45 “working poor”

- S44 (MM “Homeless Persons”) OR (MM “Indigent Persons”) OR (MM “Medically Underserved”) OR (MM “Medically Uninsured”) OR (MM “Minority Groups”) OR (MM “Transients and Migrants”)

- S43 “ill-housed persons”

- S42 “social stigma”

- S41 “social marginalization”

- S40 (MM “Work-Life Balance”)

- S39 (MM “Comfort”)

- S38 (MH “Social Class+”) OR (MM “Low Socioeconomic Status”) OR (MM “Social Mobility”)

- S37 (MM “Housing Instability”)

- S36 “economic stability”

- S35 (MH “Socioeconomic Factors+”) OR (MM “Economic Factors”) OR (MM “Economic Status”) OR (MM “Educational Status”) OR (MM “Housing Instability”) OR (MM “Low Socioeconomic Status”) OR (MH “Social Class+”) OR (MM “Social Mobility”) OR (MM “Unemployment”)

- S34 TX “child poverty”

- S33 (MM “Child Welfare”)

- S32 (MM “Poverty”)

- S31 TX (“low income” or “low-income” or needy or indigent or impoverished or destitute or penniless or “poverty-stricken” or “poverty stricken” or necessitous or straitened or “lower class” or “lower-class”)

- S30 (MM “Public Housing”)

- S29 (MH “Europeans+”) OR (MM “Eastern Europeans”) OR (MM “Scandinavians and Nordic Persons”) OR (MM “White Persons”)

- S28 S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27

- S27 TX “black communit*” or “health inequity” or “health inequality” or “black Canadian*” or “african canadian” or caribbean or “caribbean and black commmunit* racial disparit*” or intersectionality or race

- S26 (MM “Stereotyping”)

- S25 (MH “Racism+”) OR (MM “Systemic Racism”)

- S24 TX dene

- S23 TX cree OR TX haudenosaunee OR TX metis

- S22 TX “first nation*”

- S21 (MH “Ethnic Groups+”) OR (MH “Africans+”) OR (MM “Arabs”) OR (MH “Asians+”) OR (MH “Australasians+”) OR (MH “Black Persons+”) OR (MH “Indigenous Peoples+”) OR (MH “Jews+”) OR (MM “Kurds”) OR (MM “Middle Eastern Persons”) OR (MH “North Americans+”) OR (MM “Aboriginal Canadians”) OR (MH “African Americans”) OR (MM “Amish”) OR (MH “Hispanic Americans”) OR (MM “Inuit”) OR (MH “Native Americans”) OR (MM “Roma”) OR (MM “South Americans”)

- S20 (MM “Special Populations”)

- S19 (MM “Minority Groups”)

- S18 “health disparate”

- S17 (MM “Refugees”)

- S16 “population groups”

- S15 (MH “Undocumented Immigrants”)

- S14 (MM “Emigration and Immigration”)

- S13 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S11 OR S12

- S12 TX “sars cov 2”

- S11 TX “sever acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR TX “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” OR TX wuhan

- S10 TX “2019-nCov disease” OR TX “2019 ncov infection” OR TX “coronavirus disease 19”

- S9 TX 2019-nCoV OR TX COVID-19 OR TX “2019 novel coronavirus disease”

- S8 TX CoV OR TX SARS-CoV OR TX MERS-CoV

- S7 TX “middle east respiratory syndrome” OR TX severe acute respiratory syndrome” AND TX SARS

- S6 TX coronavirus* OR TX “corona virus” OR TX mers

- S5 MH covid 19

- S4 MW covid

- S3 (MH “SARS Virus”)

- S2 (MH “Coronavirus Infections+”) OR (MM “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome”) OR (MH “COVID-19+”) OR (MH “Coronavirus+”) OR (MH “SARS-CoV-2”)

- S1 MH coronavirus

Appendix B. Grey Literature Search Terms

| Context (Applied in Conjugation with the Boolean Operator “AND”) | Target Location (Applied in Conjugation with the Boolean Operator “AND”) | Target Interest (Applied in Conjugation with the Boolean Operator “AND”) | Target Population (Applied in Conjugation with the Boolean Operator “AND”) |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | racialized communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | homeless |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | essential workers (Boolean operator NOT healthcare workers) |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | African communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | migrant workers |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | low-income |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | truckers |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | Caribbean communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | racial + minoritized |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | housing challenged |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | Asian communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | South Asian communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | South American |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | North African communities |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | Middle eastern |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | grocery clerks |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | minimum wage workers |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | displaced refugees |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | transient shelter |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | retail workers |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | restaurant staff |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | farmers |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | immigrants |

| COVID-19 | Canada | impact | Indigenous |

Appendix C. Data Extraction Instructions and Data Fields

| General information | |

| Title | |

| Lead author | |

| Year of publication | |

| Publication source | |

| Countries in which the study conducted | |

| Province/territory in which the study conducted | |

| Study Characteristics | |

| Methods | Aim of study |

Study design

| |

| Details of study design | |

| Data source | |

| Context | |

| Participants | Total population size (N) |

| Population description | |

| Sample size of interest (n) | |

| Age | |

| Gender | |

| Income | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Other demographic information | |

| Outcomes | Reported Impact on Health outcomes (quantitative) |

| Reported Impact on Health outcomes (qualitative) | |

| Reported Impact on Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) (quantitative) | |

| Reported Impact on Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) (qualitative) | |

| Reported Impact on Health inequities (quantitative) | |

| Reported Impact on Health inequities (qualitative) | |

| Comparator(s) (group/outcomes) | |

| Reported Effect on Comparator | |

| Other sociodemographic variables | |

References

- Mein, S.A. COVID-19 and Health Disparities: The Reality of “the Great Equalizer”. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2439–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, K.M.; Benner, A.D. The racialized landscape of COVID-19: Reverberations for minority adolescents and families in the U.S. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 52, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razai, M.S.; Kankam, H.K.N.; Majeed, A.; Esmail, A.; Williams, D.R. Mitigating ethnic disparities in COVID-19 and beyond. BMJ 2021, 372, m4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.; Homan, P.A.; García, C.; Brown, T.H. The Color of COVID-19: Structural Racism and the Disproportionate Impact of the Pandemic on Older Black and Latinx Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e75–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Kolady, D. The COVID-19 pandemic’s unequal socioeconomic impacts on minority groups in the United States. Demogr. Res. 2022, 47, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemei, J.; Tulli, M.; Olanlesi-Aliu, A.; Tunde-Byass, M.; Salami, B. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Black Communities in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearby, R.; Mohapatra, S. Law, structural racism, and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Law Biosci. 2020, 7, lsaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, P.; Williams, E.; Bishay, A.E.; Farah, I.; Tamayo-Murillo, D.; Newton, I.G. The Roots of Structural Racism in the United States and their Manifestations During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad. Radiol. 2021, 28, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Social Determinants and Inequities in Health for Black Canadians: A Snapshot. 2020. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health/social-determinants-inequities-black-canadians-snapshot.html (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Inequalities in Health of Racialized Adults in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/inequalities-health-racialized-adults-18-plus-canada.html (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- McKoy, D.L.; Vincent, J.M. Housing and education: The inextricable link. In Segregation: The Rising Costs for America; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, P.J.; Chateau, D.G.; Burland, E.M.J.; Finlayson, G.S.; Smith, M.J.; Taylor, C.R.; Brownell, M.D.; Nickel, N.C.; Katz, A.; Bolton, J.M. The Effect of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status on Education and Health Outcomes for Children Living in Social Housing. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2103–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, A.K.; Maharaj, S. Socio-Economic Segregation Between Schools in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/123895/1/RIES%20-%20Technical%20Report%20-%20Socio-Economic%20Segregation.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Herman, J. Canada’s Approach to School Funding. 2013. Available online: https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/HermanCanadaReport.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Heard-Garris, N.; Boyd, R.; Kan, K.; Perez-Cardona, L.; Heard, N.J.; Johnson, T.J. Structuring Poverty: How Racism Shapes Child Poverty and Child and Adolescent Health. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, S108–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A. Unequal Opportunity: School and Neighborhood Segregation in the USA. Race Soc. Probl. 2020, 12, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, N.; Leahy, R.; Restrepo, N.J.; Lupu, Y.; Sear, R.; Gabriel, N.; Jha, O.K.; Goldberg, B.; Johnson, N.F. Online hate network spreads malicious COVID-19 content outside the control of individual social media platforms. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K.T.; Villarreal, A. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 epidemic on employment: Differences by immigrant status and race/ethnicity. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, F.A. The Racial Gap in Employment and Layoffs during COVID-19 in the United States: A Visualization. Socius Sociol. Res. A Dyn. World 2021, 7, 237802312098839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, G. Racialized identity and health in Canada: Results from a nationally representative survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeiha, M.; Artyukh, I.; Ogundele, O.J.; Zhao, J.; Massaquoi, N.; Liu, H.; Straus, S.; Razak, F.; Hosseini, B.; Shahidi, F.V.; et al. Social Inequalities in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review Protocol. 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/y538c/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006; Volume 1, p. b92. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Currie, C.L.; Higa, E.K. The Impact of Racial and Non-racial Discrimination on Health Behavior Change Among Visible Minority Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezezika, O.; Girmay, B.; Mengistu, M.; Barrett, K. What is the health impact of COVID-19 among Black communities in Canada? A systematic review. Can. J. Public Health 2023, 114, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, C.; Cooper, J.; Theivendrampillai, S.; Pham, B.; Straus, S.E. Exploring Canadian perceptions and experiences of stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1068268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlick, S.; Chatwood, S. Exploring community perspectives on the impacts of COVID-19 on food security and food sovereignty in Nunavut communities. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, R.F.; Padgett, J.K.; Cila, J.; Sasaki, J.Y.; Lalonde, R.N. The reemergence of Yellow Peril: Beliefs in the Asian health hazard stereotype predict lower psychological well-being. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2022, 13, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A.; Kurl, S.; Zhang, Y.S.D.; Young-Leslie, H. Chinese Canadians’ experiences of the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and racism: Implications for identity, negative emotion, and anti-racism incident reporting. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2022, 63, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A.; Kurl, S.; Zhang, Y.S.D.; Young-Leslie, H. COVID discrimination experience: Chinese Canadians’ social identities moderate the effect of personal and group discrimination on well-being. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2023, 29, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miconi, D.; Li, Z.Y.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Santavicca, T.; Cénat, J.M.; Venkatesh, V.; Rousseau, C. Ethno-cultural disparities in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study on the impact of exposure to the virus and COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma on mental health across ethno-cultural groups in Quebec (Canada). BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmani, A.I.; Abdi, K.; Mabrouk, E.B.; Zhao, T.; Salami, B.O.; Jones, A.; Tong, H.; Salma, J. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Muslim older immigrants in Edmonton, Alberta: A community-based participatory research project with a local mosque. Can. J. Public Health 2023, 114, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, M.; Lane, G.; Szafron, M.; Hillier, K.; Pahwa, P.; Vatanparast, H. Exploring the Implications of COVID-19 on Food Security and Coping Strategies among Urban Indigenous Peoples in Saskatchewan, Canada. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling Cameron, E.; Ramos, H.; Aston, M.; Kuri, M.; Jackson, L. “COVID affected us all”: The birth and postnatal health experiences of resettled Syrian refugee women during COVID-19 in Canada. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M. The social ecology of COVID-19 prevalence and risk in Montreal, QC, Canada. Health Place 2022, 78, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Bui van Snell, A.N.; Howell, R.T.; Bailis, D. Daily self-compassion protects Asian Americans/Canadians after experiences of COVID-19 discrimination: Implications for subjective well-being and health behaviors. Self Identity 2022, 21, 891–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.; Lee, C.; Wang, A.H.; Guruge, S. Immigrants’ and refugees’ experiences of access to health and social services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Toronto, Canada. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2023, 28, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, I. Inequality, Employment and COVID-19 Priorities for Fostering an Inclusive Recovery in BC. 2021. Available online: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2021/07/ccpa-bc_Inequality-Employment-COVID_full.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Canadian Labour Congress. CLC Submission to the Government of Canada on Labour Shortages, Working Conditions and the Care Economy. 2022. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/441/HUMA/Brief/BR11689927/br-external/CanadianLabourCongress-e.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Gladu, M. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women. 2021. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2021/parl/xc71-1/XC71-1-1-432-6-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Public Health Ontario. COVID-19 in Ontario—A Focus on Neighbourhood Diversity, February 26, 2020 to December 31, 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/epi/2020/06/covid-19-epi-diversity.pdf?la=en#:~:text=The%20most%20diverse%20neighbourhoods%20in,diverse%20neighbourhoods%20(Table%201) (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Ontario Health; Wellesley Institute. Tracking COVID 19 Through Race-Based Data. 2021. Available online: https://www.ontariohealth.ca/system/equity/report-covid-19-race-based-data (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Statistics Canada. COVID-19 in Canada: A One-Year Update on Social and Economic Impacts. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2021001-eng.htm (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- The Ottawa Local Immigration partnership. The Impact of COVID-19 on Immigrants & Racialized Communities in Ottawa: A Community Dialogue. 2020. Available online: https://olip-plio.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SummaryReport-OLIP-COVID-CommunityDialogue.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Impacts on Immigrants and People Designated as Visible Minorities. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/2020004/s6-eng.htm (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Statistics Canada. The Social and Economic Impacts of COVID-19: A Six-Month Update. 2020. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/statcan/11-631-x/11-631-x2020004-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Cheff, R.; Elliott, S.; Afful, A.; Opoku, E. Mapping the Impacts of COVID-19 on Hotel Workers in the GTA. 2023. Available online: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/COVID-and-Hotel-Workers.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Health and Safety of Agricultural Temporary Foreign Workers in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/att__e_43972.html (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- The Migrant Workers Alliance for Change. Unheeded Warnings: COVID-19 & Migrant Workers in Canada. 2020. Available online: https://migrantworkersalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Unheeded-Warnings-COVID19-and-Migrant-Workers.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Sanford, S.; Um, S.; Tolentino, M.; Raveendran, L.; Kharpal, K.; Weston, N.A.; Roche, B. COVID-19 and Racialized Communities: Impacts on Mental Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Mental-Health-and-Well-being-A-Focus-on-Racialized-Communities-in-the-GTA.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Fearon, G.; Hejazi, W.; Ciologariu, A.; Murray, S.; Younes, R.; Salti, S.; Abdo, R. Experiences of Racialized Communities During COVID-19 Reflections and a Way Forward. 2021. Available online: https://brocku.ca/community-engagement/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/Final-Brock-Report.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- African-Canadian Civic Engagement Council; Innovative Research Group. Impact of COVID-19: Black Canadian Perspectives. 2020. Available online: https://innovativeresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ACCEC01-Release-Deck.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- The Black Health Alliance. Perspectives on Health & Well-Being in Black Communities in Toronto. 2020. Available online: https://blackhealthalliance.ca/wp-content/uploads/Perspectives-on-Health-Well-Being-in-Black-Communities-in-Toronto-Experiences-through-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Access to STBBI-Related Health Services, Including Harm Reduction Services, for African, Caribbean and Black (ACB) People in Canada? Government of Canada. 2 June 2022. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/datalab/covid-19-stbbi-acb-people.html (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Housing Challenges Remain for Vulnerable Populations in 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220721/dq220721b-eng.pdf?st=M_nrEN1a (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Kuang, S.; Earl, S.; Clarke, J.; Zakaria, D.; Demers, A.; Aziz, S. Experiences of Canadians with Long-Term Symptoms Following COVID-19. 2023. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00015-eng.htm (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Bleakney, A.; Masoud, H.; Robertson, H. Labour Market Impacts of COVID-19 on Indigenous People Living off Reserve in the Provinces: March 2020 to August 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00037-eng.htm (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Hahmann, T.; Kumar, M.B. Unmet Health Care Needs During the Pandemic and Resulting Impacts Among First Nations People Living off Reserve, Métis and Inuit. 2022. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2022001/article/00008-eng.htm (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Mashford-Pringle, A.; Skura, C.; Stutz, S.; Yohathasan, T. What We Heard: Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/indigenous-peoples-covid-19-report/cpho-wwh-report-en.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Thompson, S.; Bonnycastle, M.; Hill, S. COVID-19, First Nations and Poor Housing. 2020. Available online: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Manitoba%20Office/2020/05/COVID%20FN%20Poor%20Housing.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice. Another Year: Anti-Asian Racism Across Canada Two Years into the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2022. Available online: https://ccncsj.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Anti-Asian-Racism-Across-Canada-Two-Years-Into-The-Pandemic_March-2022.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Sakamoto, I.; Lin, K.; Tang, J.; Lam, H.; Yeung, B.; Nhkum, A.; Cheung, E.; Zhao, K.; Quan, P. 2020 in Hindsight: Intergenerational Conversations on Anti-Asian Racism During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://socialwork.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2020-in-Hindsight-English.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- The Angus Reid Institute. Blame, Bullying and Disrespect: Chinese Canadians Reveal Their Experiences with Racism During COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://angusreid.org/racism-chinese-canadians-covid19/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Canadian Labour Congress. Canadian Workers to Political Leaders: It’s High Time for Paid Sick Leave. Canadian Labour Congress. Available online: https://canadianlabour.ca/canadian-workers-to-political-leaders-its-high-time-for-paid-sick-leave/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Borras, A.M. The political economy of racialized health inequities: A panoramic view. In Handbook on the Social Determinants of Health; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijer, G.; King, D. The Racialized Pandemic: Wave One of COVID-19 and the Reproduction of Global North Inequalities. Perspect. Politics 2022, 20, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi Dimeglio, P.; Fullilove, R.E.; Cecchi, C.; Cabon, Y.; Rosenberg, J. Predicting COVID-19 infection and death rates among E.U. minority populations in the absence of racially disaggregated data through the use of US data comparisons. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccardi, F.; Tan, P.S.; Shah, B.R.; Everett, K.; Clift, A.K.; Patone, M.; Saatci, D.; Coupland, C.; Griffin, S.J.; Khunti, K.; et al. Ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes: A multinational cohort study of 20 million individuals from England and Canada. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerschbaumer, L.; Crossett, L.; Holaus, M.; Costa, U. COVID-19 and health inequalities: The impact of social determinants of health on individuals affected by poverty. Health Policy Technol. 2024, 13, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Calhoun, B.H.; Kucik, J.E.; Konnyu, K.J.; Hilson, R. Exploring the association of paid sick leave with healthcare utilization and health outcomes in the United States: A rapid evidence review. Glob. Health J. 2023, 7, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochford, H.I.; Le, A.B. Impact of Earned Sick Leave Policy on Worker Wellbeing Across Industries. Saf. Health Work 2025, 16, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Taffe, B.D.; Richmond, J.A.; Roberson, M.L. Racial discrimination and health-care system trust among American adults with and without cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscou, K.; Bhagaloo, A.; Onilude, Y.; Zaman, I.; Said, A. Broken Promises: Racism and Access to Medicines in Canada. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 11, 1182–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Country | Study Design | Population | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Canada | Quantitative | Racialized adults in Alberta | To examine the differential impacts of racial and non-racial discrimination on health behavior change in the first wave of the pandemic, as compared to visible minority adults who did not experience discrimination during this period. |

| [26] | Canada | Systematic review | Black populations across Canada | To identify the health impact of COVID-19 on mortality, morbidity, hospital admission, and hospital readmission rates in the Black population across Canada. |

| [27] | Canada | Quantitative | Ontario residents | To explore perceptions and experiences of stigma among Ontario residents by gender, age, and race/ethnicity. |

| [28] | Canada | Qualitative | Community members from Iqaluit and Arviat (Nunavut) | To document the impacts of COVID-19 outbreaks and associated funding programs, and to explore community perspectives on these impacts to provide insights into how food security and food sovereignty may be better supported in Nunavut in the future. |

| [28] | Canada | Qualitative | Immigrants and refugees residing in Toronto or the Greater Toronto Area, Ontario | To explore how immigrants and refugees experienced access to health and social services during the first wave of COVID-19 in Toronto, Canada. |

| [29] | US and Canada | Mixed methods | Adult Asian Americans and Asian Canadians | To measure the content of the Asian health hazard stereotype, and to investigate the association between beliefs that this stereotype is held by others and psychological well-being for East and Southeast Asian Americans and Canadians specifically (but not exclusively) during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| [30] | Canada | Quantitative | Chinese Canadian (CC) adults | To examine how the rise in anti-Chinese discrimination, in addition to the threats posed by the COVID-19, have affected not only CCs’ well-being, but also their Chinese and Canadian identities. |

| [31] | Canada | Quantitative | Chinese Canadian (CC) adults | To investigate (a) whether perceived personal and group discrimination make distinct contributions to CCs negative affect and concern that the heightened discrimination they experienced during the pandemic will continue after the pandemic; (b) whether Canadian and Chinese identities and social support moderate the effect of discrimination on this concern; and (c) whether race-based rejection sensitivity (RS) explains why each type of discrimination predicts negative affect and expectation of future discrimination. |

| [32] | Canada | Quantitative | A culturally diverse sample of adults in Quebec | To investigate the association of exposure to the virus, COVID-19-related discrimination, and stigma with mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, in a culturally diverse sample of adults in Quebec (Canada). |

| [33] | Canada | Mixed methods | Muslim older immigrants aged 50+, living in Edmonton, Alberta | To explore the experiences of Muslim older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify ways to build community resilience as part of a community-based participatory research partnership with a mosque in Edmonton, Alberta. |

| [34] | Canada | Mixed methods | Indigenous (including First Nations and Métis) adults living in urban areas of Saskatchewan | To examine the impact of the pandemic and related lockdown measures on the food security of urban Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan, Canada. |

| [35] | Canada | Qualitative | Postnatal re-settled Syrian refugee women in Nova Scotia with a child under 12 months of age | To understand Syrian refugee women’s experiences with accessing postnatal healthcare services and supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| [36] | Canada | Quantitative | Residents of 15 neighborhoods in Montreal, Quebec | To examine the social ecology of COVID-19 risk exposure across Montreal by comparing fifteen neighborhoods with contrasting COVID-19 prevalence. |

| [37] | US and Canada | Mixed methods | Asian American and Asian Canadian students | To explore if self-compassion was associated with subjective well-being and protective behaviors for American and Canadian Asians who faced COVID-19 discrimination. |

| References | Sample Size, N: Sample of Interest *, n: Race/Ethnic Composition | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| [25] | N = 986 *; n = 210 * Researchers excluded the data for those who identified as Caucasian. (Race/ethnic composition of (n): Asian (54.8%), Indigenous (10.5%), African American (9.0%), Middle Eastern (6.2%), Latino (4.3%), and mixed race/ethnicity (17.6%)) |

|

| [26] | N/A |

|

| [27] | N = 1823; n = 1227 (Racial/ethnic composition of (N): 33% White, 26% East/Southeast Asian, 14% Black, 12% South Asian). |

|

| [28] | N = 7; n = 7 (Racial/ethnic composition: 100% Indigenous) | Key themes included the following:

|

| [38] | N = 72; n = 72 (Country of origin (N) by %: Pakistan: 15.3%, China: 15.3%, Bangladesh: 9.7%, Afghanistan 6.9%, South Korea: 6.9%, India: 6.9%, Syria: 5.6%, Philippines: 5.6%, other: 27.8% |

|

| [29] | N = 703; n = 351 * * Participants who identified as Chinese Canadians |

|

| [30] | N = 874; n = 874 (Racial/ethnic composition: Chinese Canadian 100%, first generation (G1) 71.9%, second generation (G2) 28.1%) |

|

| [31] | N = 516; n = 516 (Racial/ethnic composition: Chinese Canadian 100%) |

|

| [32] | N = 3273; n = 1667 (Racial/ethnic composition of (N): 49.07% White, 7.61% East Asian, 2.93% South Asian, 21.14% Black, 3.64% Southeast Asian, 13.75% Arab, 1.86% Other) |

|

| [33] | N = 104; n = 104 (Place of birth: 14.7% Ethiopia, 28.4% Lebanon, 19.3% Somalia, 37.5% Other) |

|

| [34] | N = 130; n = 130 (Racial/ethnic composition: 100% Indigenous) |

|

| [35] | N = 8; n = 8 (Racial/ethnic composition: 100% Syrian refugee) |

|

| [36] | N = 1,704,694 (15 neighborhoods), Visible minority: 34.2% |

|

| [37] | N = 127; n = 42 (Racial/ethnic composition of (n): 100% Asian Canadian) |

|

| Racialized Populations (General) | |

|---|---|

| [39] | Employment and Income: Overrepresented in low-wage jobs and most economically disrupted; higher workplace exposure risk linked to mortality disparities. |

| [40] | Gender and Race Wage Gaps: Racialized and immigrant women experienced the lowest earnings, especially in care work. |

| [41] | Employment: Racialized women were more severely affected by job losses (e.g., South Asian women had 20.4% unemployment vs. 11.3% national rate). Childcare Access: Limited access to affordable childcare hindered workforce participation. |

| [42] | Infection Disparities: Most racially diverse neighborhoods had 1.6× higher infection, 2.0× higher hospitalization/ICU rates, and 2.6× higher death rates. |

| [43] | Infection Disparities: racialized Ontarians had 1.2–7.1× higher infection and 1.7–7.6× higher death rates compared to white Ontarians. |

| [42] | Higher Infection and Severity in Diverse Neighborhoods:

|

| [44] | Higher COVID-19 Mortality in Racialized Areas: areas where visible minorities make up 25% or more of the population had COVID-19 mortality rates about twice as high as areas with less than 1% visible minority population. Urban Impact: these disparities were largely concentrated in Canada’s largest cities:

Visible minority groups continue to face higher unemployment, more financial hardship, and greater representation in low-wage work. |

| [45] | Disproportionate COVID-19 Impact: racialized groups in Ottawa were overrepresented among those testing positive for COVID-19, according to early data from June 2020. Systemic Barriers: systemic racism and discrimination limited access to stable employment, placing many racialized individuals in high-risk frontline roles (e.g., cleaners, ride-share drivers). Workplace and Transit Risks:

Challenges included lack of access to family doctors and limited awareness of available supports. Inequitable Lockdown Effects: Lockdowns disproportionately affected racialized communities due to limited living space and uneven enforcement of public health bylaws. |

| [46] | Frontline Workforce Overrepresentation:

Health Disparities by Neighborhood Diversity (Ontario): COVID-19 impacts were significantly worse in the most racially diverse neighborhoods:

|

| [47] | Disproportionate Job Loss:

|

| [48] | Hotel workers: hotel cleaning staff are typically lower-paid and predominantly female, racialized, immigrant, or migrant workers, reflecting a highly segmented workforce.

|

| [49] | Foreign Workers: temporary foreign workers experienced outbreaks despite exemptions; at least 3 deaths occurred. |

| [50] | Precarious Immigration Status: lack of permanent resident status limited migrant workers’ ability to assert their rights, protect themselves from COVID-19, access healthcare, and secure adequate housing. Wage Theft and Exploitation: wage theft was widespread, worsened by border closures that caused income loss and pressured workers to enter Canada without sufficient support. Inadequate Quarantine Measures: quarantine protocols failed to address migrant workers’ needs, leading to unpaid isolation periods, food insecurity, and restricted mobility. Discrimination and Abuse: reports of intimidation, surveillance, threats, and racism increased—particularly targeting Caribbean workers. Legal Exclusion and Overwork: existing labor laws excluded many migrant workers, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and intensified workloads. |

| [51] | Mental Health Impacts During COVID-19:

|

| Arab Canadians | |

| [52] | Economic Impact: Arab respondents were somewhat less affected economically by the COVID-19 pandemic compared to non-Arabs:

|

| [46] | In August 2020, unemployment was highest among Arab Canadians (17.9%), while the lowest was non-visible minority or Indigenous Canadians (9.4%). |

| Black/African/Caribbean Canadians | |

| [53] | Health and Financial Impact: Faced higher rates of COVID-19 symptoms, hospitalizations, and deaths; more likely to hold frontline jobs and experience income loss and housing insecurity. |

| [54] | COVID-19 infections and mortality:

|

| [55] | Mental Health: 33% reported worsened mental health; 42% attempted to access mental health services, with 62% experiencing barriers |

| [55] | Substance Use: increased use of alcohol (38%), cannabis (56%), and other substances reported; low engagement with support services |

| [55] | Food and Financial Insecurity: 61% reported financial hardship; 53% faced food insecurity since the pandemic began. |

| [56] | Economic Hardship: 40% of Black-led households experienced economic hardship during the pandemic, with 75% attributing it directly to COVID-19. Higher Unemployment: from July 2020 to June 2021, the average unemployment rate for Black individuals aged 15 to 69 was 12.9%, significantly higher than the 7.9% rate among non-racialized populations. |

| [57] | Reinfection: Black (30.3%) Canadians more frequently reported having multiple infections than Canadians with Latin American (21.7%), Chinese (18.3%), Filipino (17.9%), Arab (12.1%) and West Asian (9.1%) backgrounds. |

| Indigenous Populations | |

| [58] | Employment: Employment recovery lagged behind non-Indigenous populations; higher unemployment as of August 2021. While most occupation groups saw net employment gains in the most recent six-month period, growth was weaker in those occupations that are most common among Indigenous workers compared to the same period in 2019. |

| [47] | Greater Financial Strain: 36% of Indigenous respondents reported difficulty meeting financial obligations, versus 25% of non-Indigenous participants. |

| [59] | Healthcare Access: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people reported more unmet healthcare needs and service disruptions than non-Indigenous people. |

| [60] | Community Strength and Challenges: Highlighted community resilience, but systemic issues (housing, water access, internet, health services) exacerbated pandemic vulnerabilities. |

| [60] | Mental Health and Substance Use: Concerns about reduced access to cultural practices and misuse of CERB funds were raised. Multiple participants brought forward concerns around some individuals who used the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to purchase substances (e.g., drugs and/or alcohol). |

| [61] | Limited Healthcare Infrastructure: Most First Nations communities in isolated or remote areas have small healthcare facilities. Those needing acute COVID-19 care, such as ventilators, must be airlifted, causing logistical challenges due to limited availability of planes and helicopters. Inadequate Isolation Facilities: Isolation options for sick individuals on reserves were limited. Double Jeopardy: First Nations people faced higher health risks but had less access to necessary healthcare services. Housing Challenges: Poor quality, inadequate, and unsafe housing on reserves increased COVID-19 exposure and vulnerability for First Nations populations. |

| South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Chinese Canadians | |

| [62] | Anti-Asian Racism:

|

| [63] | Chinese Canadians: Experienced widespread anti-Asian racism, often unreported due to internalized doubt and social pressures. |

| [64] | Widespread Experiences of Racism: In total, 50% of the respondents reported being called names or insulted due to COVID-19; 43% faced threats or intimidation. In total, 30% of the respondents encountered racist graffiti or social media messages, and 29% frequently felt they were viewed as a threat to others’ health. Perceived Blame and Belonging:

|

| [46] | High Exposure and Job Loss Risk: Visible minorities were more concentrated in hard-hit sectors like food and accommodation—especially Korean (19.1%), Filipino (14.2%), and Southeast Asian (14.0%) Canadians. |

| [47] | Rising Harassment and Stigma:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komeiha, M.; Artyukh, I.; Ogundele, O.J.; Zhao, Q.J.; Massaquoi, N.; Straus, S.; Razak, F.; Hosseini, B.; Persaud, N.; Mishra, S.; et al. Unveiling the Impact: A Scoping Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Racialized Populations in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071054

Komeiha M, Artyukh I, Ogundele OJ, Zhao QJ, Massaquoi N, Straus S, Razak F, Hosseini B, Persaud N, Mishra S, et al. Unveiling the Impact: A Scoping Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Racialized Populations in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071054

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomeiha, Menna, Iryna Artyukh, Oluwasegun J. Ogundele, Q. Jane Zhao, Notisha Massaquoi, Sharon Straus, Fahad Razak, Benita Hosseini, Navindra Persaud, Sharmistha Mishra, and et al. 2025. "Unveiling the Impact: A Scoping Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Racialized Populations in Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071054

APA StyleKomeiha, M., Artyukh, I., Ogundele, O. J., Zhao, Q. J., Massaquoi, N., Straus, S., Razak, F., Hosseini, B., Persaud, N., Mishra, S., Eissa, A., Isabel, M., & Pinto, A. D. (2025). Unveiling the Impact: A Scoping Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effects on Racialized Populations in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071054