Upholding the Right to Health in Contexts of Displacement: A Whole-of-Route Policy Analysis in South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Migration, Displacement, and Health in the SDGs

- Refugees: individuals whose asylum claim has been recognised and accepted.

- Internally displaced persons (IDPs): individuals who are those forced to flee their homes due to armed conflict, violence, human rights violations, or disasters, without crossing an international border [13].

- Undocumented migrants: foreign-born individuals residing in a country without legal authorisation to enter, remain, or work there [14].

1.2. Displacement as a Determinant of Health

1.3. National Health Systems in Context

1.4. Conceptual Framework: Legal Classification, Health Governance, and Multi-Level Policy Regimes

1.5. Securitisation, Systemic Exclusion, and Structural Invisibility

2. Methodology

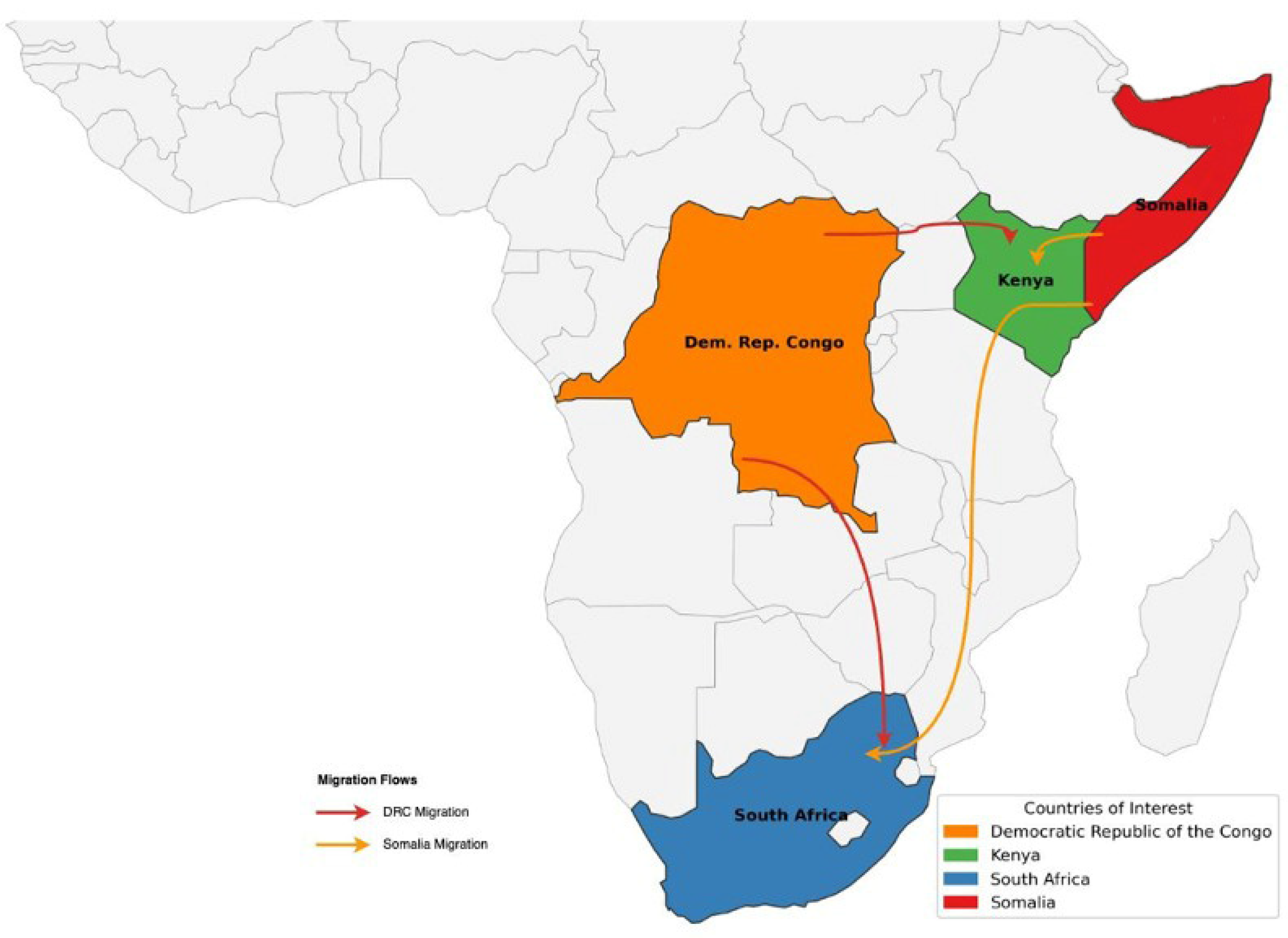

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Key Informant Interviews

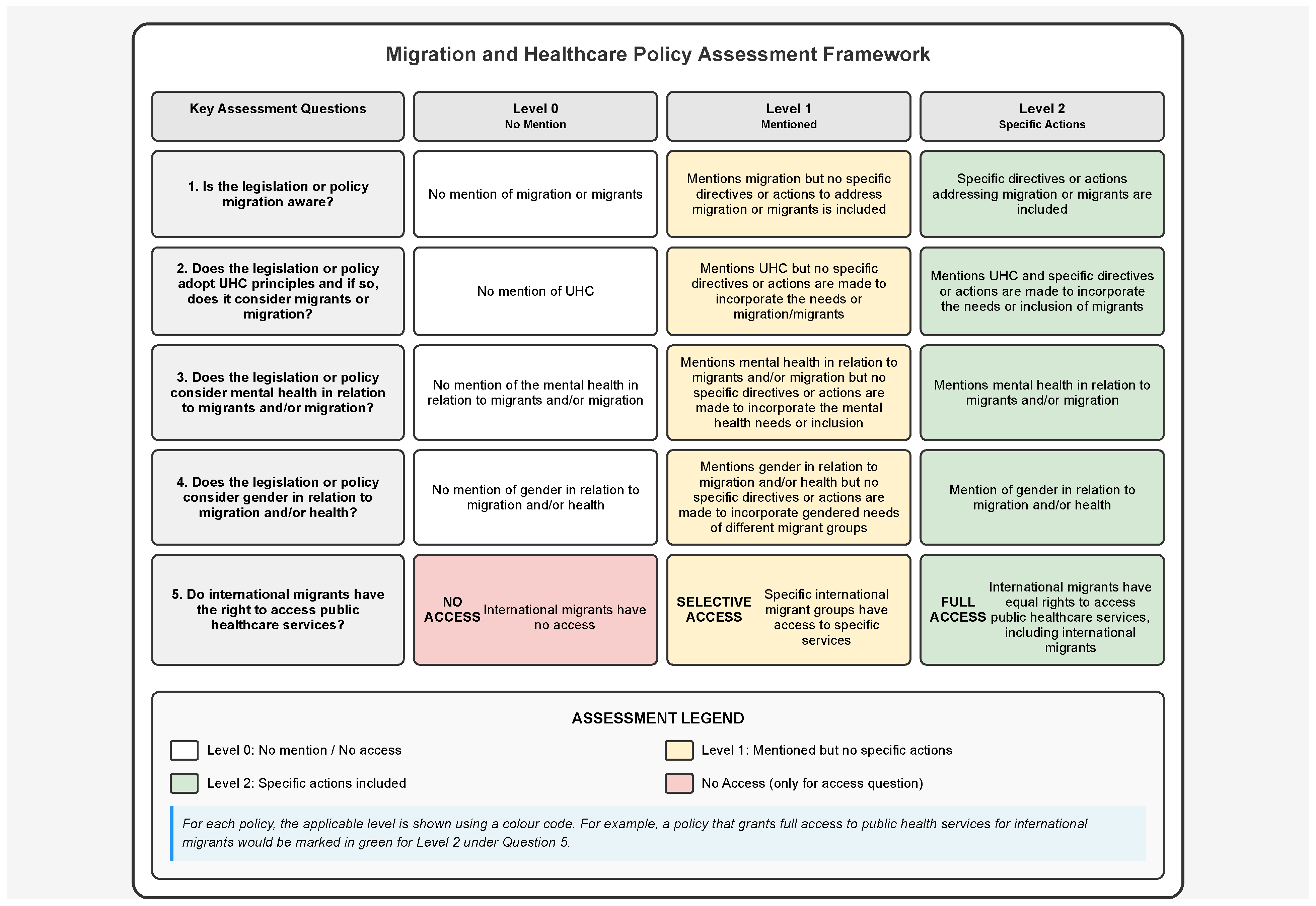

2.4. Policy and Legal Document Review

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

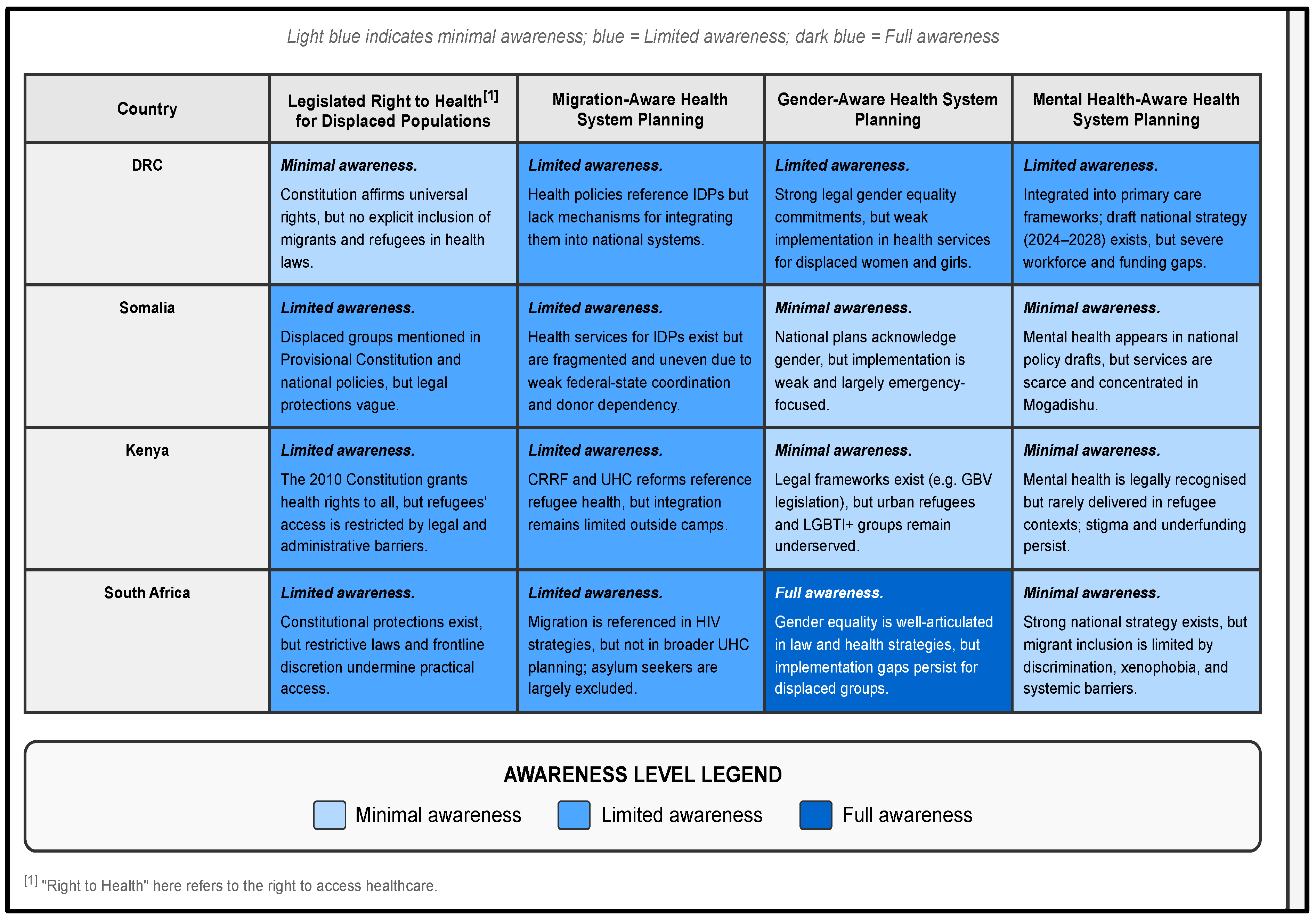

3.1. Gaps Between UHC Commitments and Healthcare Access

“The NHI is sending mixed signals—only some get the so-called universal access, for others, it categorises people and the most vulnerable are the most excluded”(KII, SA 03).

“Even though refugees are entitled in theory, in practice, the system still asks for documents they cannot easily produce”(KII, Kenya 01).

“It is impossible to implement our health plans fully because all our activities rely on funding from the donor community”(KII, Somalia 04).

“There’s a strong will to act, but the system is overloaded. For migrants, access depends on ad hoc decisions at the facility level”(KII, DRC 01).

3.2. Limited Migration Awareness in Health Systems Planning

“Migrant health isn’t really planned for—it’s still left to the NGOs and project budgets.”(KII, Kenya 03)

“Access depends on how you are treated at the facility, not on your rights.”(KII, SA 02)

3.3. Neglect of Mental Health Needs

“There’s a strong will to act, but the system is overloaded… access depends on ad hoc decisions.”(KII, DRC 01)

“Mental health is a forgotten component of health services in Somalia, not only for IDPs but for even the general population.”(KII, Somalia 11)

“Mental health remains underfunded and understaffed.”(KII, Kenya 02)

“Migrants are effectively invisible in mental health service delivery.”(KII SA 05)

3.4. Insufficient Gender-Sensitive Health Programming

“We have to prioritise essential packages such as maternal and child health.”(KII, Somalia 02)

3.5. Structural Barriers to Inclusive Health Systems

“When humanitarian funding stops, the clinics for displaced people often close too.”(KII, DRC)

3.6. Synthesis of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. From Normative Commitment to Implementation: The Reality of Policy–Practice Gaps

4.2. Migration-Blind Systems and the Limits of National Health Planning

4.3. Mental Health as a Neglected Pillar of Displacement Health

4.4. Gender, Intersectionality, and the Reproduction of Inequality

4.5. Civil Society’s Role and the Crisis of Sustainability

4.6. Toward Transformative Health Governance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ODI. Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.sloga-platform.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Migration-and-the-2030-Agenda-for-Sustainable-Development.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- IOM. Migration Health in the Sustainable Development Goals. Position Paper. 2020. Available online: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/our_work/DMM/Migration-Health/mhd_position_paper_sdgs_02.09.2020_en.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/291/89/pdf/n1529189.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Adger, W.N.; Fransen, S.; de Campos, R.S.; Clark, W.C. Migration and sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2206193121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N.; Boyd, E.; Fábos, A.; Fransen, S.; Jolivet, D.; Neville, G.; De Campos, R.S.; Vijge, M.J. Migration transforms the conditions for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e440–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, E.M.; Laczko, F. Migration and the SDGs: Measuring Progress—An Edited Volume; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-and-sdgs-measuring-progress-edited-volume (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- IOM. Migration and the 2030 Agenda. A Guide for Practitioners; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration—A/RES/73/195; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Compact on Refugees—A/73/12; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/Global%20compact%20on%20refugees%20EN.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future: Sustainable Development Report 2024; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. The Geneva Convention Refugees. 1951. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=geneva+convention+refugees&sca_esv=c2c5be54cb889fa4&rlz=1C5CHFA_enZA928ZA928&sxsrf=ACQVn0_LFpgA_YfoTClxlJfvZVfKisMfGA%3A1708278549594&ei=FUPSZczjI6-jhbIP4reAuA8&oq=geneva+convention+refugees&gs_lp=Egxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAiGmdlbmV2YSBjb252ZW50aW9uIHJlZnVnZWVzKgIIADILEAAYgAQYigUYkQIyBRAAGIAEMgUQABiABDIGEAAYFhgeMgYQABgWGB4yBhAAGBYYHjIGEAAYFhgeMgYQABgWGB4yBhAAGBYYHjIGEAAYFhgeSKEjUOkGWOAXcAF4AZABAJgByAKgAfwTqgEFMi04LjG4AQHIAQD4AQHCAgoQABhHGNYEGLADwgINEAAYgAQYigUYQxiwA8ICChAAGIAEGIoFGEPCAgsQABiABBiKBRiGA4gGAZAGCg&sclient=gws-wiz-serp (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- African Union. OAU Convention: Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. 1969. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36400-treaty-36400-treaty-oau_convention_1963.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- UNHCR. 2009 Kampala Convention on IDPs. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5cd569877.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- IOM. Glossary on Migration; No. 34; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Zetter, R. More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization. J. Refug. Stud. 2007, 20, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.K.; Liu, H.; Liang, L.; Ho, J.; Kim, H.; Seong, E.; Bonanno, G.A.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Hall, B.J. Everyday life experiences and mental health among conflict-affected forced migrants: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Refugees and Migrants: Risk and Protective Factors and Access to Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373279/9789240081840-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Newbold, K.B. Understanding the Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Context of Mental Health Challenges: A Systematic Critical Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, C.; Ali, S.; Roberts, B.; Stewart, R. A Systematic Review of Resilience and Mental Health Outcomes of Conflict-Driven Adult Forced Migrants. Confl. Health 2014, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaramoorthy, T.; Carney, M.A. Immigration, Mental Health and Psychosocial Well-being. Med. Anthropol. 2021, 40, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.Y.; Liddell, B.J.; Nickerson, A. The Relationship Between Post-Migration Stress and Psychological Disorders in Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaiban, H.A.; Grasser, L.R.; Javanbakht, A. Mental Health of Refugees and Torture Survivors: A Critical Review of Prevalence, Predictors, and Integrated Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z.B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Challenges in the Provision of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care to Refugee and Migrant Women: A Q Methodological Study of Health Professional Perspectives. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.; Van Meyel, R.; Harder, H.; Sukhera, J.; Luc, C.; Ganjavi, H.; Elfakhani, M.; Wardrop, N. Assessing trauma in a transcultural context: Challenges in mental health care with immigrants and refugees. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AFRO; WHO. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) in WHO African Region: The SRHR Initiative. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-rights-srhr-who-african-region-srhr-initiative (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Abubakar, I.; Aldridge, R.W.; Devakumar, D.; Orcutt, M.; Burns, R.; Barreto, M.L.; Dhavan, P.; Fouad, F.M.; Groce, N.; Guo, Y.; et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: The health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018, 392, 2606–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-Agudelo, E.; Kim, H.-Y.; Musuka, G.N.; Mukandavire, Z.; Akullian, A.; Cuadros, D.F. Associated health and social determinants of mobile populations across HIV epidemic gradients in Southern Africa. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Refugee Agency UNHCR. A Route-Based Approach. Strengthening Protection and Solutions in the Context of Mixed Movements of Refugees and Migrants. 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/explainer_unhcr_route_based_approach.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Crisp, J. The Road to Nowhere? A Critique of the “Route-Based Approach” to Migration and Asylum. Refugee Law Initiative Blog. Available online: https://rli.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2025/03/07/the-road-to-nowhere-a-critique-of-the-route-based-approach-to-migration-and-asylum/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Maple, N.; Reardon-Smith, S.; Black, R. Immobility and the containment of solutions: Reflections on the Global Compacts, Mixed Migration and the Transformation of Protection. Interventions 2021, 23, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensburg, R. Healthcare in South Africa: How Inequity Is Contributing to Inefficiency. The Conversation. Available online: http://theconversation.com/healthcare-in-south-africa-how-inequity-is-contributing-to-inefficiency-163753 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Vearey, J. Global and Regional Governance Frameworks Shaping Responses to Migration, Displacement and Health in the African Union and the Eastern and Southern African Regions. April 2025. Governing Migration & Health in Africa, 30 April 2025. Available online: https://mighealth-policy-africa.org/global-and-regional-governance-frameworks-shaping-responses-to-migration-displacement-and-health-in-the-african-union-and-the-eastern-and-southern-african-regions/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- IOM. Migrants Rights to Health in Southern Africa_2022.pdf. Available online: https://ropretoria.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl691/files/documents/Migrants%20Rights%20to%20Health%20in%20Southern%20Africa_2022.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Moses, M.W.; Korir, J.; Zeng, W.; Musiega, A.; Oyasi, J.; Lu, R.; Chuma, J.; Di Giorgio, L. Performance assessment of the county healthcare systems in Kenya: A mixed-methods analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutombo, P.B.W.B.; Lobukulu, G.L.; Walker, R. Mental healthcare among displaced Congolese: Policy and stakeholders’ analysis. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2024, 5, 1273937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Government of Somalia. Somalia Recovery and Resilience Framework 2018. Summary Report; Ministry of Planning, Investment and Economic Development and the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs & Disaster Management, the Federal Member States and the Benadir Regional Administration, Federal Government of Somalia: Mogadishu, Somalia, 2018.

- Said, A.S.; Kicha, D.I. Implementing health system and the new federalism in Somalia: Challenges and opportunities. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1205327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeyink, C.; Ali-Salad, M.A.; Baruti, E.W.; Bile, A.S.; Falisse, J.B.; Kazamwali, L.M.; Mohamoud, S.A.; Muganza, H.N.; Mukwege, D.M.; Mahmud, A.J. Pathways to care: IDPs seeking health support and justice for sexual and gender-based violence through social connections in Garowe and Kismayo, Somalia and South Kivu, DRC. J. Migr. Health 2022, 6, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1948; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- World Health Organisation. WHO Global Action Plan on Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants, 2019–2030; World Health Organisation (Europe): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378211/9789240093928-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- African Centre for Migration & Society. South Africa. GMH-Afro Global Governance Frameworks Shaping Responses to Migration, Displacement and Health. Governing Migration & Health in Africa: Resource Document #1. Available online: https://mighealth-policy-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2025-global-r01-25.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- African Union Commission. Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018–2030); African Union Commission: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- African Centre for Migration & Society. Global Governance Frameworks Shaping Responses to Migration, Displacement and Health. Governing Migration & Health in Africa: Resource Document #2. The African Centre for Migration & Society: Johannebsurg, South Africa. 2025. Available online: https://mighealth-policy-africa.org/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Oelgemöller, C. The Global Compacts, Mixed Migration and the Transformation of Protection. Interventions 2021, 23, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanopoulos, E.; Guild, E.; Weatherhead, K. Securitisation of Borders and the UN’s Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration; SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3099996; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3099996 (accessed on 21 May 2018).

- African Union. Africa Health Strategy 2016–2030|African Union. Available online: https://au.int/en/documents/30357/africa-health-strategy-2016-2030 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Yates, N.; Surender, R. Southern social world-regionalisms: The place of health in nine African regional economic communities. Global Social Policy 2020, 21, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SADC. Policy Framework for Population Mobility and Communicable Diseases in the SADC Region. Final Draft; SADC: Gaborone, Botswana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Prioritizing the Health of Refugees and Migrants: An Urgent, Necessary Plan of Action for Countries and Regions in Our Interconnected World. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/18-03-2022-prioritizing-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-an-urgent-necessary-plan-of-action-for-countries-and-regions-in-our-interconnected-world?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Wickramage, K.; Vearey, J.; Zwi, A.B.; Robinson, C.; Knipper, M. Migration and health: A global public health research priority. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. Behind the Masks: Mental Health, Marginalisation and COVID-19. The Polyphony. Available online: https://thepolyphony.org/2021/09/21/behind-the-masks-mental-health-and-marginalisation-covid-19/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. “Let’s manage the stressor today” exploring the mental health response to forced migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. IJMHSC 2022, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vearey, J.; de Gruchy, T.; Maple, N. Global health (security), immigration governance and Covid-19 in South(ern) Africa: An evolving research agenda. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US State Department. Human Rights Country Report DRC. Available online: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/415610_CONGO-DEM-REP-2022-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). The DRC: Internal Displacement Overview 2024. Available online: https://drcongo.iom.int/en/news/internal-displacement-overview-2024-published (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- National-Mental-Health-Policy-Framework-2013-2020.pdf. Available online: http://www.safmh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/National-Mental-Health-Policy-Framework-2013-2020.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Storeng, K.T.; Béhague, D.P. ‘“Lives in the balance”: The politics of integration in the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lafrenière, J.; Sweetman, C.; Thylin, T. Introduction: Gender, humanitarian action and crisis response. Gend. Dev. 2019, 27, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Vearey, J. Punishment over Protection: A Reflection on Distress Migrants, Health, and a State of (Un)care in South Africa. Health Hum. Rights 2024, 26/2, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J.; Tawodzera, G. Medical Xenophobia and Zimbabwean Migrant Access to Public Health Services in South Africa. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vearey, J.; Luginaah, I.; Magitta, N.F.; Shilla, D.J.; Oni, T. Urban health in Africa: A critical global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Gleicher, D. Governance for health in the 21st Century. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326429/9789289002745-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Kihato, C.W.; Landau, L.B. Stealth Humanitarianism: Negotiating Politics, Precarity and Performance Management in Protecting the Urban Displaced. J. Refug. Stud. 2017, 30, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019–2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health. Art. no. WHO/MSD/19.1, 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/310981 (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Mills, C. From “Invisible Problem” to Global Priority: The Inclusion of Mental Health in the Sustainable Development Goals. Dev. Change 2018, 49, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Rasmussen, A. War experiences, daily stressors and mental health five years on: Elaborations and future directions. Intervention 2014, 12, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docrat, S.; Lund, C.; Chisholm, D. Sustainable financing options for mental health care in South Africa: Findings from a situation analysis and key informant interviews. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2019, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.R.; Grown, C.; Fewer, S.; Gupta, R.; Nowrojee, S. Beyond gender mainstreaming: Transforming humanitarian action, organizations and culture. Int. J. Humanit. Action 2023, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmary, I. The Normalization of Violence: Gender, Sexuality and Asylum. In Gender, Sexuality and Migration in South Africa: Governing Morality; Palmary, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiralal, K.; Jinnah, Z. (Eds.) Gender and Mobility in Africa: Borders, Bodies and Boundaries; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2023 Global Monitoring Report; World Health Organization and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240080379 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Walker, R.; Richter, M. Op Ed: Calls for self-reliance must not deter SA’s efforts to fight US funding freeze. BusinessLIVE. Available online: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2025-02-28-calls-for-self-reliance-must-not-deter-sas-efforts-to-fight-us-funding-freeze/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- White, J.A.; Rispel, L.C. Policy exclusion or confusion? Perspectives on universal health coverage for migrants and refugees in South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 1292–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | UHC Strategy | Implementation Status | Attention to Displaced Populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) | National Health Development Plan; UHC strategy | Policy intent exists; rollout is slow and aid-dependent | Very limited inclusion of displaced groups; weak, ad hoc, and inconsistent |

| Somalia | Essential Package of Health Services (EPHS); UHC roadmap | Fragmented implementation; limited to urban centres and IDP camps | IDPs included on paper, but service delivery is weak and inconsistent |

| Kenya | UHC by 2030: Social Health Insurance Act, Primary Health Care Act, Digital Health Act | Over 17.8 million enrolled in the Social Health Authority (SHA); reforms underway | Some inclusion via SHA, but registration and documentation barriers persist for refugees and informal migrants |

| South Africa | National Health Insurance (NHI) Act: single-payer, equity-focused model | Signed into law (2024); gradual rollout; legal and financial hurdles remain | Policies acknowledge migrants but exclude asylum seekers and undocumented migrants from comprehensive coverage |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walker, R.; Vearey, J.; Bile, A.S.; Lolimo, G.L. Upholding the Right to Health in Contexts of Displacement: A Whole-of-Route Policy Analysis in South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071042

Walker R, Vearey J, Bile AS, Lolimo GL. Upholding the Right to Health in Contexts of Displacement: A Whole-of-Route Policy Analysis in South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071042

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, Rebecca, Jo Vearey, Ahmed Said Bile, and Genèse Lobukulu Lolimo. 2025. "Upholding the Right to Health in Contexts of Displacement: A Whole-of-Route Policy Analysis in South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071042

APA StyleWalker, R., Vearey, J., Bile, A. S., & Lolimo, G. L. (2025). Upholding the Right to Health in Contexts of Displacement: A Whole-of-Route Policy Analysis in South Africa, Kenya, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071042