A Community-Engaged Approach to Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment for Public Health Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Utility of a Community Health Needs (And Assets) Assessment

1.2. CBPR-Focused Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment

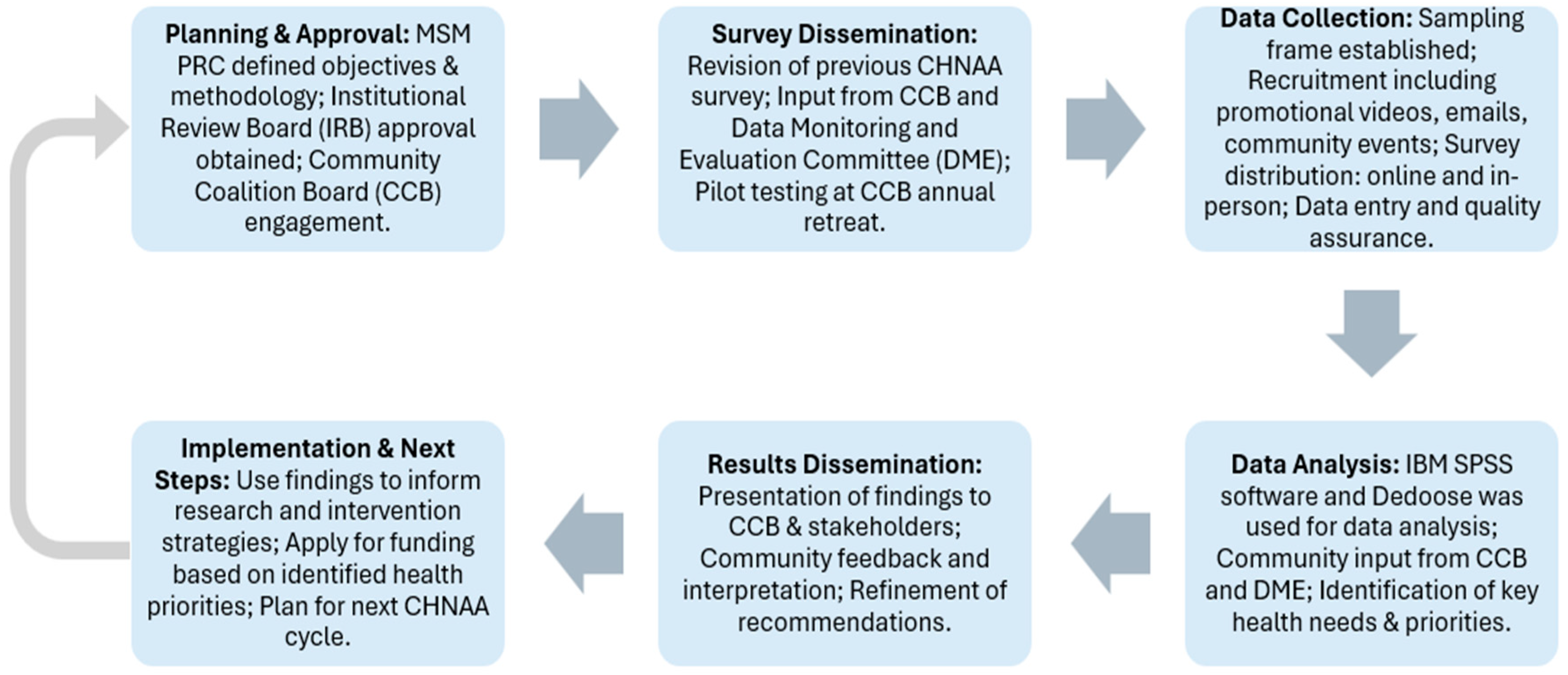

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CHNAA Survey Instrument Development

2.2. CHNAA Administration

2.2.1. Sampling Methods

| The City of Atlanta is divided into twenty-five (25) Neighborhood Planning Units (NPUs), which are citizen advisory councils that make recommendations to the Mayor and City Council on zoning, land use, and other planning-related matters. Source: Neighborhood Planning Units| Atlanta, GA |

2.2.2. CHNAA Data Collection Methods

2.2.3. Data Analysis Methods

3. Results

3.1. CHNAA Quantitative Findings

3.2. CHNAA Qualitative Findings

“They tend to run in my family so being more educated would definitely help better understand or at least know where to seek help.” Another individual cited, “Because these diseases are afflicting me and my family.”

“Lack of health education, health screening programs…” Another individual stated“Businesses that have better/cleaner options aren’t in the neighborhood. Grocery stores don’t make it a priority to provide fresh produce.”

“Creating health screening and education programs, offering free/low-cost primary health care and incentives (free medicine and supplies) to working people for adhering to treatment and control of these issues.”

3.3. CCB-Engagement Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Challenges and Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CEnR | Community-Engaged Research |

| CHNA | Community Health Needs Assessment |

| CHNAA | Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment |

| Continuum of CEnRCCB | Continuum of Community-Engaged ResearchCommunity Coalition Board |

| DME | Data Monitoring and Evaluation |

| MSM | Morehouse School of Medicine |

| MSM-PRC | Morehouse School of Medicine Prevention Research Center |

| NPU | Neighborhood Planning Unit |

| PRC | Prevention Research Center |

| SVI | Social Vulnerability Index |

References

- Groseclose, S.L.; Buckeridge, D.L. Public Health Surveillance Systems: Recent Advances in Their Use and Evaluation. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.; Ritchie, C. Research Participation in Marginalized Communities—Overcoming Barriers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Health Justice. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adds a New Principle of Community Engagement; Center For Health Justice: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.aamchealthjustice.org/news/news/centers-disease-control-and-prevention-adds-new-principle-community-engagement (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Ahmed, S.; Anise, A.; Azzahir, A.; Baker, K.; Cupito, A.; Eder, M.; Everette, T.D.; Erwin, K.; Felzien, M.; et al. Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement: A Conceptual Model to Advance Health Equity through Transformed Systems for Health. NAM Perspectives 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, B.; Vries, J. Community Engagement in Global Health Research That Advances Health Equity. Bioethics 2018, 32, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alang, S.; Batts, H.; Letcher, A. Interrogating Academic Hegemony in Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Inequities. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2020, 26, 135581962096350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balls-Berry, J.E.; Acosta-Pérez, E. The Use of Community Engaged Research Principles to Improve Health: Community Academic Partnerships for Research. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2017, 36, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer, N.L.; Bekemeier, B.; Van Raemdonck, L.; Hoover, A.G. Applying Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership Principles to Public Health Practice-Based Research Networks. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 215824401667921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, K.D.; Furr-Holden, D.; Lewis, E.Y.; Cunningham, R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Selig, S. The Continuum of Community Engagement in Research: A Roadmap for Understanding and Assessing Progress. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2019, 13, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, L.; Gordon, T.K.; Proeller, A.; Ross, T.; Phillips, A.; Ward, C.; Hopkins, M.; Burney, R.; Bojnowski, W.; Hoffman, L.; et al. Community-Based Strategies for Health Priority Setting and Action Planning. Am. J. Health Stud. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintobi, T.H.; Quarells, R.C.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Khizer, S.; Taylor, B.D.; Nwagwu, M.N.A.; Hill, M.; Ordóñez, C.E.; Sabben, G.; Spivey, S.; et al. Community-Centered Assessment to Inform Pandemic Response in Georgia (US). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.; Schulz, A.; Parker, E.; Becker, A. Community-Based Participatory Research: Policy Recommendations for Promoting a Partnership Approach in Health Research. Educ. Health Change Learn. Pract. 2001, 14, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintobi, T.H.; Jacobs, T.; Sabbs, D.; Holden, K.; Braithwaite, R.; Johnson, L.N.; Dawes, D.; Hoffman, L. Community Engagement of African Americans in the Era of COVID-19: Considerations, Challenges, Implications, and Recommendations for Public Health. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, 200255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, N.; Francis, S.; Evans, B.; Parker, A.; Dorsey, J.; Glass, D.; Whitfield, M.; Blasingame, E.; Braxton, P.; Chandler, R. Research Protocol Addressing Maternal Mental Health among Black Perinatal Women in Atlanta, Georgia: A CBPR approach. J. Ga. Public Health Assoc. 2022, 8, 107–117. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1307&context=jgpha (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- McCuistian, C.; Peteet, B.; Burlew, K.; Jacquez, F. Sexual Health Interventions for Racial/Ethnic Minorities Using Community-Based Participatory Research: A Systematic Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 50, 109019812110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, C.M.; Johnson-Hakim, S.; Anglin, A.; Connelly, C. Putting the Community Back into Community Health Needs Assessments: Maximizing Partnerships via Community-Based Participatory Research. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2017, 11, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, E.E.; McDonald, K. We Are “Both in Charge, the Academics and Self-Advocates”: Empowerment in Community-Based Participatory Research. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röger-Offergeld, U.; Kurfer, E.; Brandl-Bredenbeck, H.P. Empowerment through Participation in Community-Based Participatory Research-Effects of a Physical Activity Promotion Project among Socially Disadvantaged Women. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1205808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, D.S. A Community Coalition Board Creates a Set of Values for Community-Based Research. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3, A16. [Google Scholar]

- Akintobi, T.H.; Hoffman, L.; Turpin, R.; Conner, C.; O’Quinn, M.; Okoye, D. Establishing Community Governance. In Community-Centered Public Health: Strategies, Tools, and Applications for Advancing Health Equity; Akintobi, T.H., Stephanie, M.-R., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Akintobi, T.H.; Barrett, R.; Hoffman, L.F.; Scott, S.D.; Finn Davis, K.; Jones, T.S.; Brown, N.J.; Fraire, M.G.; Montaño Fraire, R.; Garner, J.S.; et al. The Community Engagement Course and Action Network: Strengthening Community and Academic Research Partnerships to Advance Health Equity. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1114868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaghi, H.; Guisset, A.-L.; Elfeky, S.; Nasir, N.; Khani, S.; Ahmadnezhad, E.; Abdi, Z. A Scoping Review of Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment: Concepts, Rationale, Tools and Uses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Community Commons. An Introduction to Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA). 2025. Available online: https://www.communitycommons.org/collections/An-Introduction-to-Community-Health-Needs-Assessment-CHNA (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Applying Research Principles to the Community Health Needs Assessment Process; Health Research & Educational Trust: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.aha.org/ahahret-guides/2016-07-15-applying-research-principles-community-health-needs-assessment-process (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Akintobi, T.H.; Lockamy, E.; Goodin, L.; Hernandez, N.D.; Slocumb, T.; Blumenthal, D.; Braithwaite, R.; Leeks, L.; Rowland, M.; Cotton, T.; et al. Processes and Outcomes of a Community-Based Participatory Research-Driven Health Needs Assessment: A Tool for Moving Health Disparity Reporting to Evidence-Based Action. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2018, 12, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greteman, B.; Rollins, L.; Penn, A.; Berg, A.; Nehl, E.; Llewellyn, N.; Weber, A.; George, M.; Sabbs, D.; Mubasher, M.; et al. Identifying Community-Engaged Translational Research Collaboration Experience and Health Interests of Community-Based Organizations outside of Metropolitan Atlanta. J. Ga. Public Health Assoc. 2022, 8, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC; Place and Health—Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program (GRASP). Social Vulnerability Index. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/place-health/php/svi/index.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ahmed, A.; Pereira, L.; Jane, K. Mixed Methods Research: Combining Both Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Research Gate. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384402328_Mixed_Methods_Research_Combining_both_qualitative_and_quantitative_approaches (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Archibald, M.M.; Radil, A.I.; Zhang, X.; Hanson, W.E. Current Mixed Methods Practices in Qualitative Research: A Content Analysis of Leading Journals. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27.0; [Computer Software]; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ibm.com/spss (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. Cloud Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data, Dedoose version 9.0.46; [Computer Software]; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.: Manhattan Beach, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Georgia Department of Public Health, Office of Health Indicators for Planning (OHIP). Age-Adjusted Hospital Discharge Rate, Georgia, 2019-2023. In OASIS Community Health Needs Assessment Dashboard; Georgia Department of Public Health, Office of Health Indicators for Planning (OHIP): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, J.K.; Smith, T.W.; Spires, S.; Moreland, P.; Thompson, G.; Henderson, D.; Smith, S.; Maxwell, R.; Hoffman, L.M.; Johnson, L.N.; et al. Lessons Learned from Community Partnership during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2024, 18, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, R.; Henry Akintobi, T.; Blumenthal, D.; Langley, W.M.; Montgomery Rice, V. The Morehouse Model: How One School of Medicine Revolutionized Community Engagement and Health Equity; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Humm-Delgado, D. Asset Assessments and Community Social Work Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, R.B.; Endalamaw, A.; Erku, D.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Enablers and Barriers of Community Health Programs for Improved Equity and Universal Coverage of Primary Health Care Services: A Scoping Review. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. Mental Health First Aid. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

| Project Name | Funding Time Frame | Project Description | Population of Interest | Geographic Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health First-Aid Training * | 2024–2029 | Training community members to learn, identify and manage stress and mental health. | Community members and professionals | Statewide |

| REACH ** | 2023–2028 | Component A: Addresses risk factors for chronic diseases through nutrition, family weight management and physical activity.Component B: Adult vaccination—increase demand for COVID-19 and Flu vaccines through partnership and community-based collaboration | African American and Hispanic Adults | Fulton |

| GA CEAL RESTORES ** | 2024–2029 | Family-based Diabetes prevention—family-based education to address pre-diabetes. Include mental health and civic engagement and policy advocacy training at the community level to increase support for families and address the social determinants of chronic diseases | African American and Hispanic pre-diabetic (Type 2) adults | Fulton, DeKalb, Hall and Macon Counties |

| MSM-PRC Core Research ** | 2024–2029 | Family-based Diabetes Self-Management—Family-based intervention to address challenges with disease management through practical intervention (e.g., diet and nutrition) to prevent the exacerbation of reduce risk factors through connection with and support of community-based organizations. | African American and Hispanic Type 2 diabetic adults | Atlanta Metropolitan Area and Dalton City |

| PEACH 2 * | 2023–2024 | To evaluate a community-based, adaptive home-based COVID-19 testing program with behavioral nudges delivered via mobile phone texts to increase uptake of COVID-19 testing and prevention behaviors among individuals affected by diabetes (with diabetes, at risk for diabetes, or caring for someone with diabetes). | African American and Hispanic | Statewide |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrett, R.H.; Bicego, E.J.; Cotton, T.C., III; Kegley, S.; Key, K.; Mitchell, C.S.; Farley, K.; Shahin, Z.; Hoffman, L.; Okoye, D.; et al. A Community-Engaged Approach to Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment for Public Health Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071030

Barrett RH, Bicego EJ, Cotton TC III, Kegley S, Key K, Mitchell CS, Farley K, Shahin Z, Hoffman L, Okoye D, et al. A Community-Engaged Approach to Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment for Public Health Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071030

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrett, Rosanna H., Emma Joyce Bicego, Thomas C. Cotton, III, Supriya Kegley, Kent Key, Charity Starr Mitchell, Kourtnii Farley, Zahra Shahin, LaShawn Hoffman, Dubem Okoye, and et al. 2025. "A Community-Engaged Approach to Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment for Public Health Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071030

APA StyleBarrett, R. H., Bicego, E. J., Cotton, T. C., III, Kegley, S., Key, K., Mitchell, C. S., Farley, K., Shahin, Z., Hoffman, L., Okoye, D., Washington, K., Walton, S., Burney, R., Gruner, A., Ross, T., Grant, H. W., Mooney, M. V., Sanford, L. A., & Henry Akintobi, T. (2025). A Community-Engaged Approach to Community Health Needs and Assets Assessment for Public Health Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071030