Local Landscapes, Evolving Minds: Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence on Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories in Adolescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence

1.2. Dual-State Approaches to Mental Health

1.3. Person-Centred Analysis

1.4. The Current Study

1.5. Aims and Hypotheses

- RQ1: Are Quantitatively and Qualitatively Distinct Mental Health Trajectories Observable in Adolescence?

- RQ2. Are There Neighbourhood Differences in the Likelihood of Exhibiting Different Trajectories of Life Satisfaction and Emotional Difficulties?

- RQ3. Do Associations Between Neighbourhood Deprivation and Trajectories of Life Satisfaction and Emotional Difficulties Operate through Aspects of Community Wellbeing?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Life Satisfaction

2.3.2. Emotional Difficulties

2.3.3. The Co-Op Community Wellbeing Index

2.3.4. Seamless Locales and Neighbourhood Deprivation

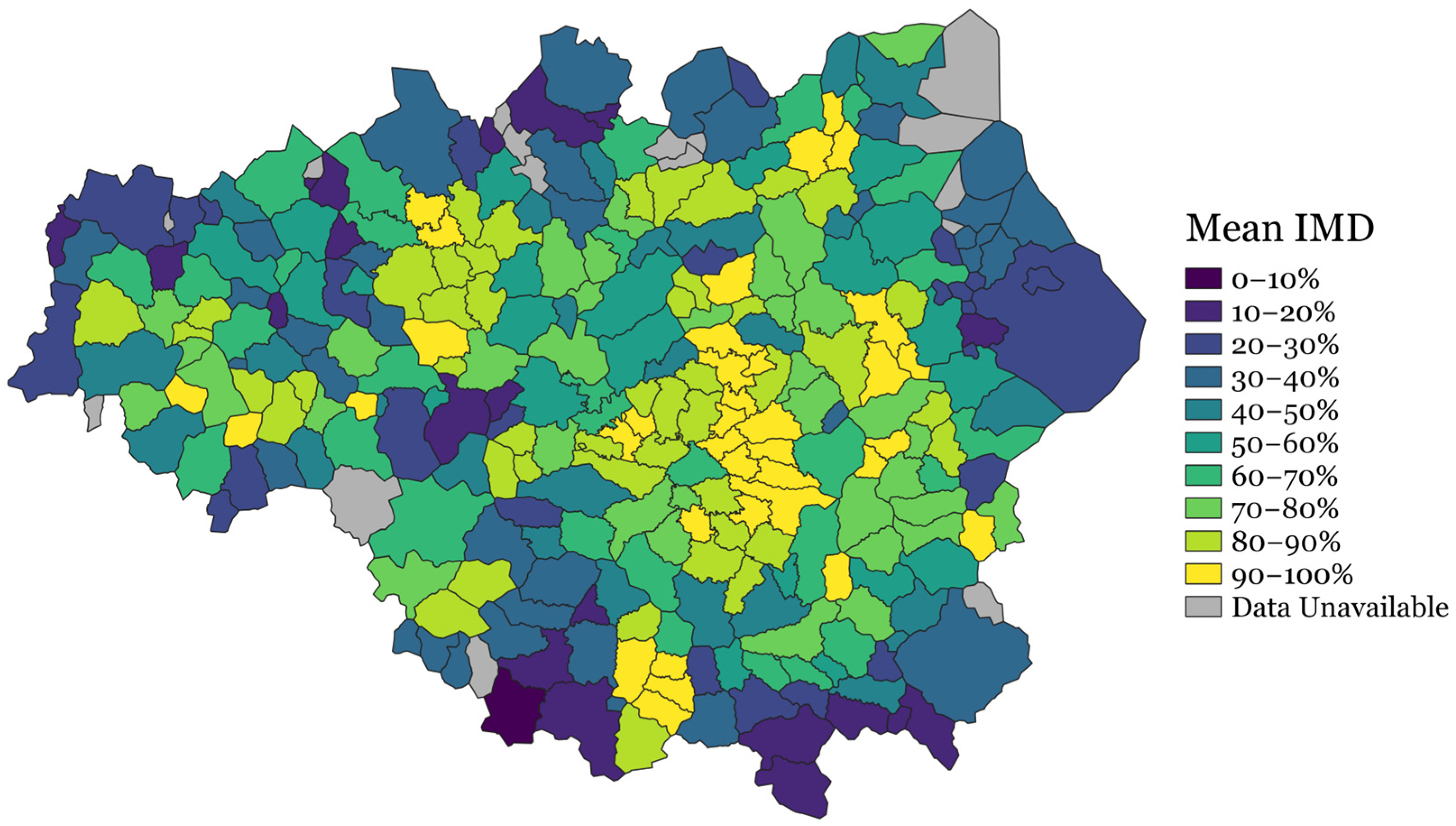

2.3.5. Covariates

2.3.6. Statistical Methods

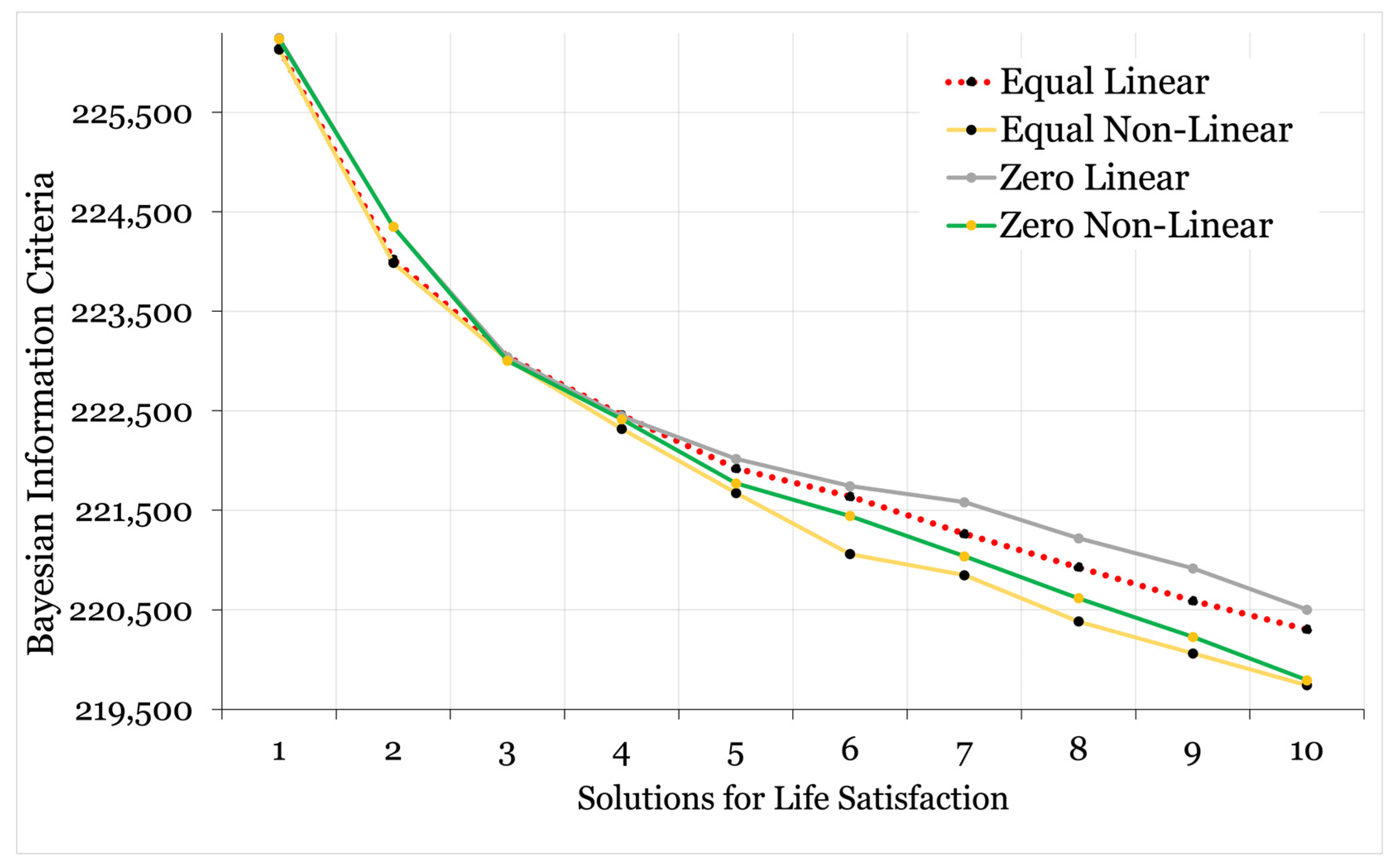

2.3.7. Phase One: Identification of the Classification Model

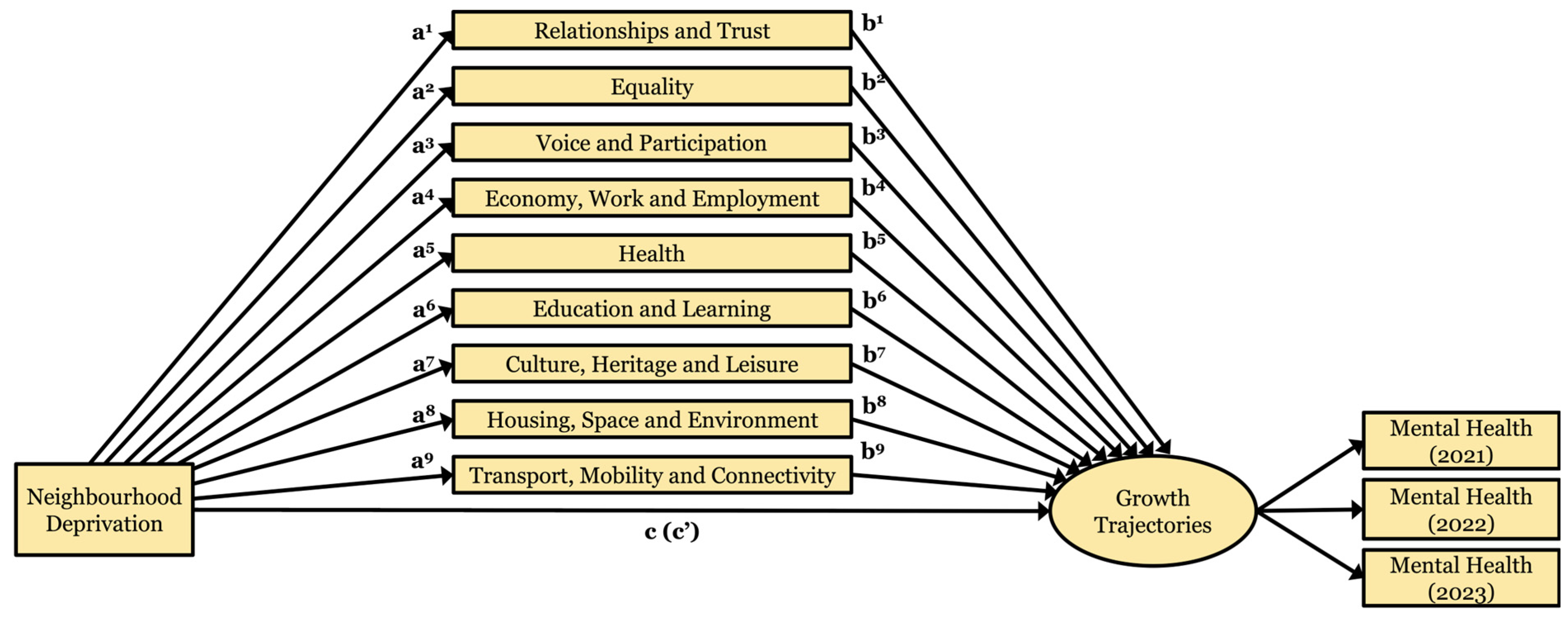

2.3.8. Phase Two: Mediation Analysis of the Structural Model

3. Results

3.1. Phase One: Identification of the Classification Model

3.1.1. Life Satisfaction Model

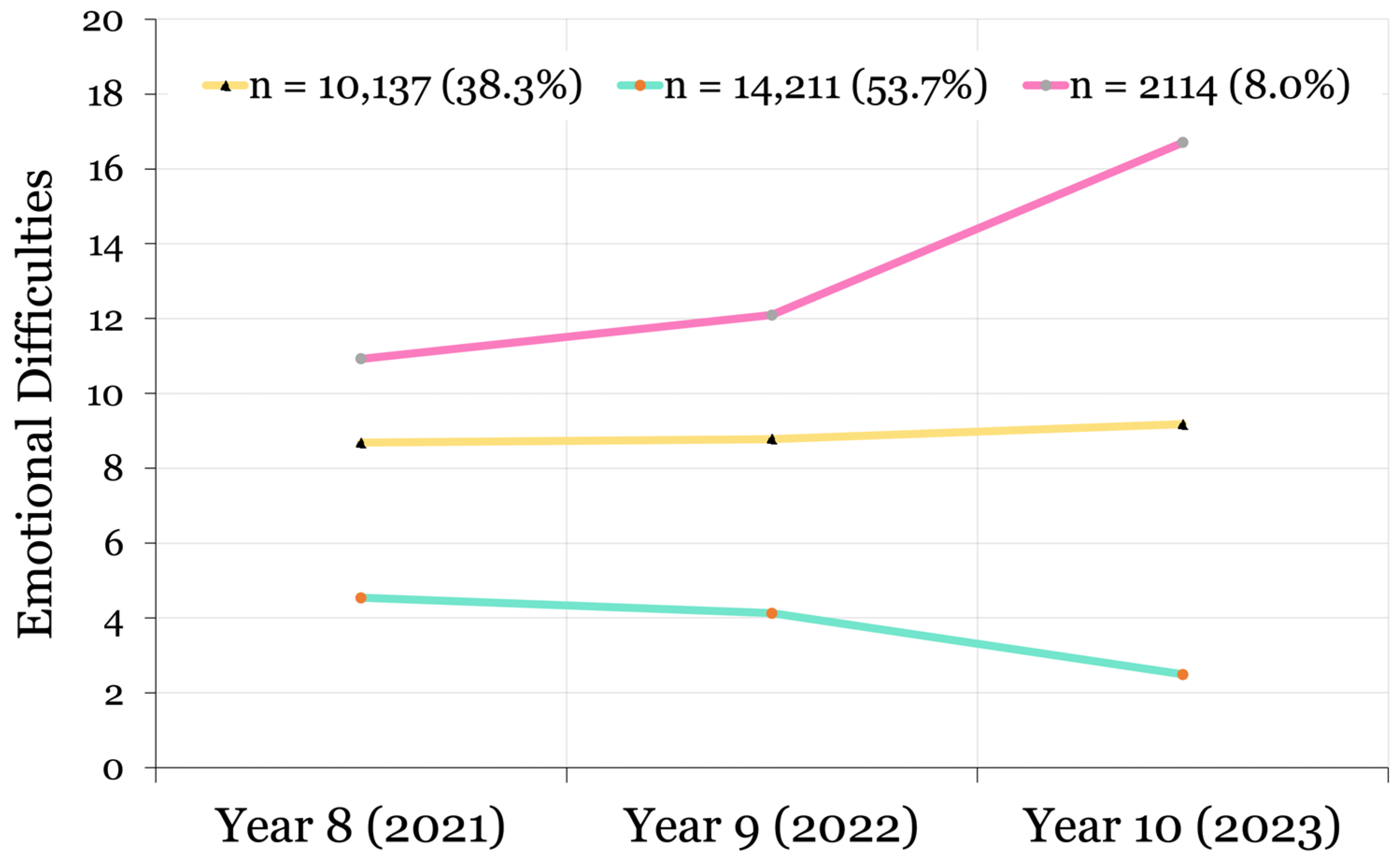

3.1.2. Emotional Difficulties Model

3.1.3. Phase Two: Multi-Level Mediation Analysis of the Structural Model

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Neighbourhood Deprivation on Life Satisfaction Trajectories

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Neighbourhood Deprivation on Emotional Difficulties Trajectories

Adjusting for Covariates

4. Discussion

4.1. Neighbourhood Deprivation

4.2. Indirect Effects Through Aspects of Community Wellbeing

4.2.1. Housing, Space, and Environment

4.2.2. Equality

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criteria |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| FIML | Full Information Maximum Likelihood |

| GM | Greater Manchester |

| H1 | Hypothesis One |

| H2 | Hypothesis Two |

| H3 | Hypothesis three |

| IMD | Index of Multiple Deprivation |

| LL | Log Likelihood |

| LMRa | Lo–Mendell–Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test |

| nb-IMD | Neighbourhood Mean Index of Multiple Deprivation Scores |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| WELLBY | Wellbeing Year |

References

- Frndak, S.; Grol-Prokopczyk, H.; Colder, C.; Banack, H.; Kordas, K. Neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent behavior problems: How do inferences differ across definitions of disadvantage? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 59, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, G.; Gavine, A.; Inchley, J.; Currie, C. Conceptualizing, measuring and evaluating constructs of the adolescent neighbourhood social environment: A systematic review. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breedvelt, J.J.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Sharples, E.; Galea, S.; Niedzwiedz, C.; Elliott, I.; Bockting, C.L. The effects of neighbourhood social cohesion on preventing depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults: Rapid review. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J.; Qualter, P.; Petersen, K.; Humphrey, N.; Black, L. Neighbourhood effects on loneliness among adolescents. J. Public Health 2023, 45, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snedker, K.; Herting, J. Adolescent mental health: Neighborhood stress and emotional distress. Youth Soc. 2016, 48, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, K.; Bolt, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Jonker, M.; Weinberg, D.; Stevens, G.W.J.M. Neighbourhood deprivation effects on young people’s mental health and well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J.; Humphrey, N.; Black, L.; Wozmirska, S. This is the place: A multi-level analysis of neighbourhood correlates of adolescent wellbeing. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 59, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; von Soest, T.; Nes, R.B. Do municipal contexts matter for adolescent mental health? A within-municipality analysis of nationwide Norwegian survey data across six years. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 52, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The association between green space and adolescents’ mental well-being: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonell, J.R.; Sianko, N. Neighborhood, neighborliness, and family and child well-being. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2021, 91, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect; University of Chicago press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Keyes, C.L.M. Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2009, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patalay, P.; Fitzsimons, E. Correlates of mental illness and wellbeing in children: Are they the same? Results from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lereya, S.T.; Patalay, P.; Deighton, J. Predictors of mental health difficulties and subjective wellbeing in adolescents: A longitudinal study. JCPP Adv. 2022, 2, e12074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Gunnell, K.E.; Gucciardi, D.F.; Lee, S. A review of some emergent quantitative analyses in sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 70–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, S.T.; Cooper, B.R. Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2016, 10, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L. Child Development; Pearson Higher Education AU: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, I.G.; McInerney, A.M.; Robinson, E.; Deschênes, S.S. Neighbourhood characteristics and socioeconomic inequalities in child mental health: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from the Growing Up in Ireland study. Health Place 2024, 86, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- #BeeWell 2025. Available online: https://beewellprogramme.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Office for National Statistics. Personal Well-Being User Guidance. 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/methodologies/personalwellbeingsurveyuserguide (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Frijters, P.; Krekel, C.; Sanchis, R.; Santini, Z.I. The WELLBY: A new measure of social value and progress. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighton, J.; Tymms, P.; Vostanis, P.; Belsky, J.; Fonagy, P.; Brown, A.; Martin, A.; Patalay, P.; Wolpert, M. The development of a school-based measure of child mental health. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2013, 31, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalay, P.; Deighton, J.; Fonagy, P.; Vostanis, P.; Wolpert, M. Clinical validity of the Me and My School questionnaire: A self-report mental health measure for children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co-Op Community Wellbeing Index. Full Report. Available online: https://communitywellbeing.coop.co.uk/media/1026/the_community_wellbeing_index_-_full_report.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Hill-Dixon, A.; Solley, S.; Byron, R. Being Well Together: The Creation of the Co-Op Community Wellbeing Index. Available online: https://communitywellbeing.coop.co.uk/#53.38690459999999,-2.3488983 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Knowles, C.; Thornton, E.; Petersen, K.; Lereya, S.T.; Humphrey, N. Latent classes of adolescent health behaviour, social covariates and mental wellbeing: A longitudinal birth cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2024, 24, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lymperopoulou, K.; Finney, N. Socio-spatial factors associated with ethnic inequalities in districts of England and Wales, 2001–2011. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2540–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, C.; Thornton, E.; Mills-Webb, K.; Petersen, K.; Marquez, J.; Stojiljković, S.; Humphrey, N. Local Landscapes, Evolving minds: Neighbourhood Predictors of Adolescent Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories (Analysis Plan). Open Science Framework. 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/94ME7 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Muthén & Muthén. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed. Available online: http://www.statmodel.com/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Hallquist, M.N.; Wiley, J.F. MplusAutomation: An R package for facilitating large-scale latent variable analyses in Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. 2018, 25, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyroud, N.; Portet, F. Introduction to QGIS. QGIS Generic Tools 2018, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781462549863. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, Y.Y.; Kruger, E.S.; Lee Van Horn, M.; Tofighi, D.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Witkiewitz, K. Latent class mediation: A comparison of six approaches. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2021, 56, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J. A primer to latent profile and latent class analysis. In Methods for Researching Professional Learning and Development; Goller, M., Kyndt, E., Paloniemi, S., Damşa, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Struct. Equ. Model. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyn, K.E. Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods; Little, T.D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 551–611. [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A.; Lucas, R.E.; Fuhrmann, D.; Kievit, R.A. Trajectories of adolescent life satisfaction. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J.; Long, E. A global decline in adolescents’ subjective well-being: A comparative study exploring patterns of change in the life satisfaction of 15-year-old students in 46 countries. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1251–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, B.; Humphrey, N.; Qualter, P. How can we improve mental health crisis services for young people? A survey of mental health crisis professionals across Greater Manchester. Discov. Health Syst. 2024, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, J.; Katsantonis, I.; Sellers, R.; Knies, G. Life satisfaction and mental health from age 17 to 21 years in a general population sample. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 27047–27057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, L.A.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Fernández-Zabala, A. Perceived academic performance explained by school climate, positive psychological variables and life satisfaction. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 93, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, J.-E.; Oswald, A.J. Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19953–19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, R.C.; Dearth-Wesley, T.; Herman, A.N.; van Wingerden, A.S.; Winn, D.W. Family connection and flourishing among adolescents in 26 countries. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021055263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiowati, N.M.; Keliat, B.A.; Wardani, I.Y.; Aldam, S.F.; Triana, R.; Florensa, M.V. Comprehending mental health in Indonesian’s adolescents through mental, emotional, and social well-being. Compr Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2019, 42, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Bassi, M.; Junnarkar, M.; Negri, L. Mental health and psychosocial functioning in adolescence: An investigation among Indian students from Delhi. J. Adolesc. 2015, 39, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venning, A.; Wilson, A.; Kettler, L.; Eliott, J. Mental health among youth in South Australia: A survey of flourishing, languishing, struggling, and floundering. Aust. Psychol. 2013, 48, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; Gombojav, N.; Whitaker, R.C. Family resilience and connection promote flourishing among US children, even amid adversity. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; de Pablo, G.S.; Shin, J.I.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newlove-Delgado, T.; Marcheselli, F.; Williams, T.; Mandalia, D.; Davis, J.; McManus, S.; Savic, M.; Treloar, W.; Ford, T. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2022—Wave 3 follow-up to the 2017 survey. In Mental Health of Children and Young People Surveys; NHS Digital: Leeds, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Maldonado, C.; Valverde, P.; Moreno, C.; Rivera, F. Direct and indirect influences of objective socioeconomic position on adolescent health: The mediating roles of subjective socioeconomic status and lifestyles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.Y.; Sinha, M.; Concepcion, T.; Patton, G.; Way, T.; McCay, L.; Mensa-Kwao, A.; Herrman, H.; de Leeuw, E.; Anand, N.; et al. Making cities mental health friendly for adolescents and young adults. Nature 2024, 627, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Access to Green Space in England. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/access-to-green-space-in-england/access-to-green-space-in-england (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Zeng, Y.; Stevens, G.W.; Helbich, M. Longitudinal associations of neighbourhood environmental exposures with mental health problems during adolescence: Findings from the TRAILS study. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanous, J.; Marquez, J.; Cheng, Q.; Irizar, P.; Mills-Webb, K.; Kapadia, D.; Humphrey, N. Ethnic Inequalities in Adolescent Mental Wellbeing: An Intersectional Analysis of Social Identity Markers, Risk and Protective Factors. Open Sci. Framework. 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/uspwg_v1 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Johnson, B.R.; Bialowolski, P.T.; Bonhag, R.; Bradshaw, M.; Breedlove, T.; Case, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Counted, V.; et al. The Global Flourishing Study: Study profile and initial results on flourishing. Nat. Ment. Health 2025, 3, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aspect of Community Wellbeing | Life Satisfaction | Emotional Difficulties |

| Education and Learning | H3a | H4a |

| Economy, Work, and Employment | H3b | H4b |

| Health | H3c | H4c |

| Culture, Heritage, and Leisure | H3d | H4d |

| Housing, Space, and Environment | H3e | H4e |

| Transport, Mobility, and Connectivity | H3f | H4f |

| Relationships and Trust | H3g | H4g |

| Equality | H3h | H4h |

| Voice and Participation | H3i | H4i |

| Life Satisfaction Model | Emotional Difficulties Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Metric | Value | Missing (%) | Value | Missing (%) | |

| Sample Size | N | 27,009 | - | 26,461 | - | |

| Schools | N | 185 | 0.00 | 179 | 0.00 | |

| Girls | n (%) | 13,477 (50.10) | 0.42 | 13,226 (50.20) | 0.40 | |

| SEN | n (%) | 4393 (16.70) | 2.83 | 4147 (16.10) | 2.70 | |

| FSM | n (%) | 7283 (27.90) | 3.43 | 7122 (27.80) | 3.34 | |

| EAL | n (%) | 5437 (20.70) | 2.68 | 5326 (20.70) | 2.57 | |

| IMD | Mean (sd) | 66.90 (22.91) | 5.49 | 66.88 (22.92) | 5.41 | |

| Ethnicity | White | n (%) | 17,217 (66.60) | 4.23 | 16,927 (66.70) | 4.14 |

| Any Other Ethnic Group | n (%) | 658 (2.50) | 4.23 | 639 (2.50) | 4.14 | |

| Asian | n (%) | 4410 (17.00) | 4.23 | 4310 (17.00) | 4.14 | |

| Black | n (%) | 1655 (6.40) | 4.23 | 1612 (6.40) | 4.14 | |

| Chinese | n (%) | 258 (1.00) | 4.23 | 255 (1.00) | 4.14 | |

| Mixed | n (%) | 1669 (6.50) | 4.23 | 1623 (6.40) | 4.14 | |

| CWI | Relationships and Trust | Mean (sd) | 0.69 (0.06) | 5.41 | 0.70 (0.06) | 5.32 |

| Equality | Mean (sd) | 0.54 (0.11) | 5.41 | 0.54 (0.11) | 5.32 | |

| Voice and Participation | Mean (sd) | 0.55 (0.08) | 5.41 | 0.55 (0.08) | 5.32 | |

| Economy, Work, and Employment | Mean (sd) | 0.66 (0.09) | 5.41 | 0.66 (0.09) | 5.32 | |

| Health | Mean (sd) | 0.53 (0.13) | 5.41 | 0.53 (0.13) | 5.32 | |

| Education and Learning | Mean (sd) | 0.87 (0.07) | 5.41 | 0.87 (0.07) | 5.32 | |

| Culture, Heritage, and Leisure | Mean (sd) | 0.71 (0.10) | 5.41 | 0.71 (0.10) | 5.32 | |

| Housing, Space, and Environment | Mean (sd) | 0.51 (0.09) | 5.41 | 0.51 (0.09) | 5.32 | |

| Transport, Mobility, and Connectivity | Mean (sd) | 0.76 (0.06) | 5.41 | 0.76 (0.06) | 5.32 | |

| Latent Class Indicator | Total Score in 2021 | Mean (sd) | 6.86 (2.48) | 32.86 | 6.60 (4.62) | 33.48 |

| Total Score in 2022 | Mean (sd) | 6.63 (2.47) | 39.49 | 6.58 (4.88) | 40.60 | |

| Total Score in 2023 | Mean (sd) | 6.62 (2.43) | 42.23 | 6.26 (4.95) | 43.11 | |

| Emotional Difficulties, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low/Lessening | Sub-Clinical | Elevated/Worsening | Missing | ||

| Life Satisfaction n (%) | Consistently High | 13,148 (47.41%) | 6823 (24.61%) | 372 (1.34%) | 1017 (3.67%) |

| Improving | 478 (1.72%) | 662 (2.39%) | 44 (0.16%) | 37 (0.13%) | |

| Deteriorating | 201 (0.73%) | 391 (1.41%) | 274 (0.99%) | 20 (0.07%) | |

| Consistently Low | 548 (1.98%) | 2330 (8.40%) | 469 (1.69%) | 195 (0.70%) | |

| Missing | 461 (1.66%) | 247 (0.89%) | 13 (0.05%) | NA | |

| Emotional Difficulties Class (vs. All Others) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Satisfaction Class (vs. All Others) | Low/Lessening | Sub-Clinical | Elevated/Worsening |

| Consistently High | 6.212 * [5.790, 6.657] | 0.301 * [0.283, 0.320] | 0.109 * [0.096, 0.124] |

| Improving | 0.519 * [0.461, 0.584] | 1.994 * [1.773, 2.242] | 0.811 [0.597, 1.103] |

| Deteriorating | 0.228 * [0.194, 0.267] | 1.263 * [1.101, 1.447] | 12.549 * [1.718, 14.700] |

| Consistently Low | 0.121 * [0.110, 0.133] | 4.222 * [3.896, 4.565] | 5.128 * [4.533, 5.797] |

| Life Satisfaction Trajectory a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Mediator | Improving | Deteriorating | Low |

| Total effect of nb-IMD (before inclusion of mediators) | ||||

| c OR [95% CI] | 0.977 [0.936, 1.020] | 1.081 [1.023, 1.142] * | 1.084 [1.051, 1.119] * | |

| Direct effect of nb-IMD (adjusted for mediators) | ||||

| c’ OR [95% CI] | 0.898 [0.832, 0.969] * | 1.087 [0.987, 1.197] | 1.133 [1.073, 1.197] * | |

| Indirect (mediated) effect (product of paths a × b) | ||||

| αb1 [95% CI] b | Rel. and Trust | 0.000 [−0.004, 0.005] | −0.001 [−0.007, 0.004] | 0.000 [−0.003, 0.003] |

| αb2 [95% CI] b | Equality | −0.007 [−0.025, 0.010] | 0.004 [−0.013, 0.021] | 0.016 [0.002, 0.029] * |

| αb3 [95% CI] b | Voice and Part. | 0.003 [−0.003, 0.009] | 0.000 [−0.008, 0.008] | −0.002 [−0.007, 0.002] |

| αb4 [95% CI] b | Ec., Work, and Empl. | 0.051 [−0.015, 0.117] | −0.014 [−0.081, 0.052] | −0.014 [−0.053, 0.025] |

| αb5 [95% CI] b | Health | 0.000 [−0.019, 0.019] | −0.007 [−0.023, 0.010] | 0.002 [−0.010, 0.013] |

| αb6 [95% CI] b | Edu. and Learn. | −0.005 [−0.018, 0.009] | 0.011 [−0.006, 0.027] | −0.007 [−0.016, 0.003] |

| αb7 [95% CI] b | Cult., Heri., and Leis. | −0.001 [−0.005, 0.003] | 0.001 [−0.004, 0.005] | 0.002 [−0.006, 0.009] |

| αb8 [95% CI] b | Hous., Spac., and Env. | 0.019 [−0.014, 0.051] | 0.026 [−0.008, 0.060] | −0.026 [−0.046, −0.006] * |

| αb9 [95% CI] b | Trans., Mob., and Conn. | 0.005 [−0.020, 0.029] | −0.028 [−0.060, 0.004] | −0.006 [−0.023, 0.010] |

| Emotional Difficulties Trajectory a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway | Mediator | Sub-Clinical | Worsening |

| Total effect of nb-IMD (before inclusion of mediators) | |||

| c OR [95% CI] | 0.975 [0.954, 0.996] * | 0.996 [0.954, 1.040] | |

| Direct effect of nb-IMD (adjusted for mediators) | |||

| c’ OR [95% CI] | 0.992 [0.952, 1.033] | 1.060 [0.985, 1.141] | |

| Indirect (mediated) effect (product of paths a*b) | |||

| αb1 [95% CI] b | Rel. and Trust | 0.000 [−0.003, 0.002] | −0.002 [−0.005, 0.002] |

| αb2 [95% CI] b | Equality | 0.005 [−0.003, 0.014] | 0.007 [−0.007, 0.020] |

| αb3 [95% CI] b | Voice and Part. | −0.004 [−0.009, 0.001] | 0.001 [−0.006, 0.007] |

| αb4 [95% CI] b | Ec., Work, and Empl. | 0.007 [−0.025, 0.040] | −0.033 [−0.083, 0.017] |

| αb5 [95% CI] b | Health | 0.006 [−0.002, 0.014] | −0.007 [−0.023, 0.009] |

| αb6 [95% CI] b | Edu. and Learn. | −0.002 [−0.009, 0.005] | −0.008 [−0.020, 0.004] |

| αb7 [95% CI] b | Cult., Heri., and Leis. | 0.000 [−0.001, 0.001] | 0.002 [−0.005, 0.008] |

| αb8 [95% CI] b | Hous., Spac., and Env. | −0.026 [−0.045, −0.008] * | −0.017 [−0.042, 0.008] |

| αb9 [95% CI] b | Trans., Mob., and Conn. | 0.010 [−0.004, 0.025] | 0.007 [−0.015, 0.029] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knowles, C.; Thornton, E.; Mills-Webb, K.; Petersen, K.; Marquez, J.; Stojiljković, S.; Humphrey, N. Local Landscapes, Evolving Minds: Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence on Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060951

Knowles C, Thornton E, Mills-Webb K, Petersen K, Marquez J, Stojiljković S, Humphrey N. Local Landscapes, Evolving Minds: Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence on Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories in Adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060951

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnowles, Christopher, Emma Thornton, Kathryn Mills-Webb, Kimberly Petersen, Jose Marquez, Sanja Stojiljković, and Neil Humphrey. 2025. "Local Landscapes, Evolving Minds: Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence on Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories in Adolescence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060951

APA StyleKnowles, C., Thornton, E., Mills-Webb, K., Petersen, K., Marquez, J., Stojiljković, S., & Humphrey, N. (2025). Local Landscapes, Evolving Minds: Mechanisms of Neighbourhood Influence on Dual-State Mental Health Trajectories in Adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 951. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060951