Feasibility Study for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Aromatherapy Footbath for Stimulating Onset of Labor in Term Pregnant Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

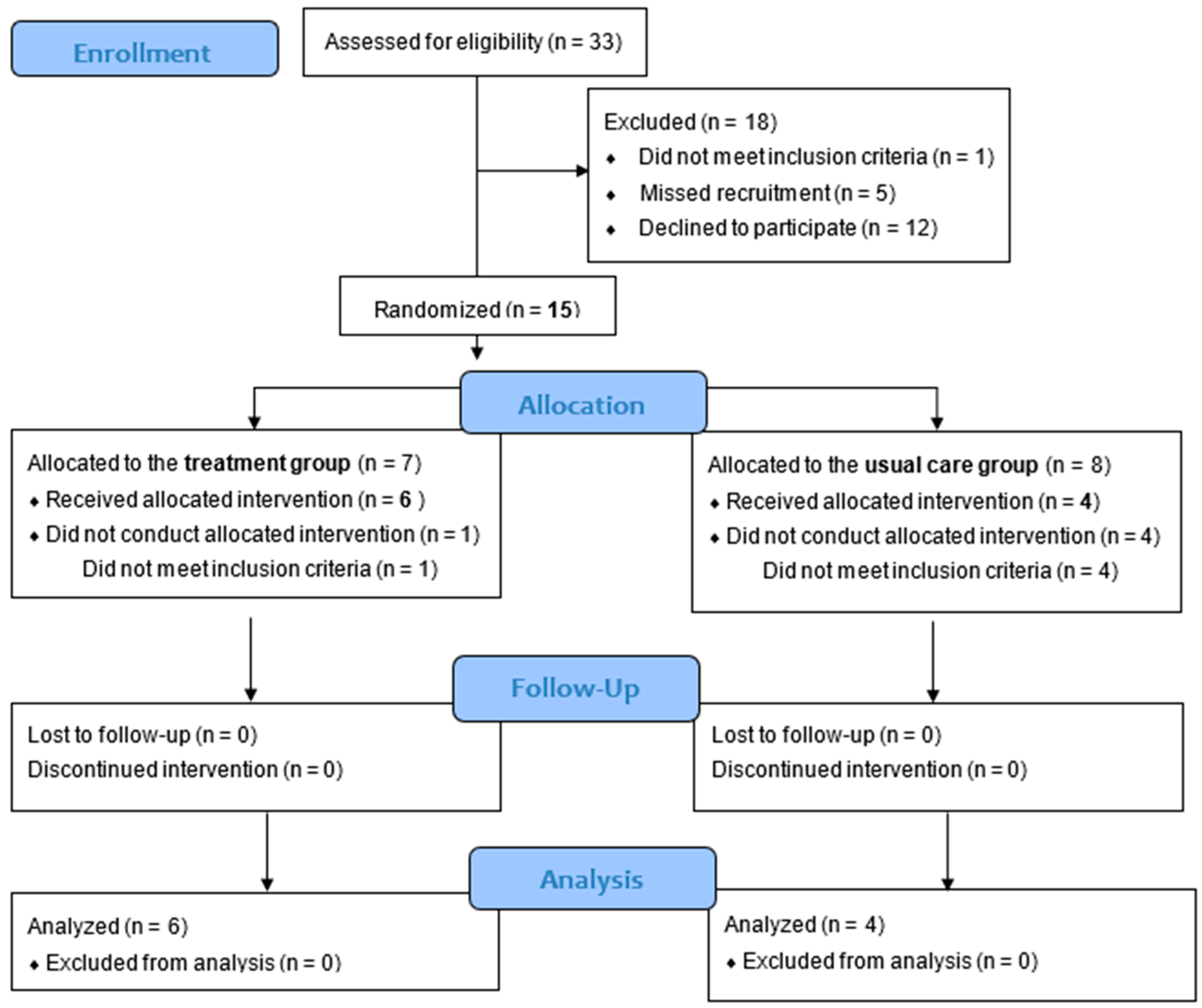

2.2. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

2.2.1. Participants and Sample Size

2.2.2. Randomization and Masking

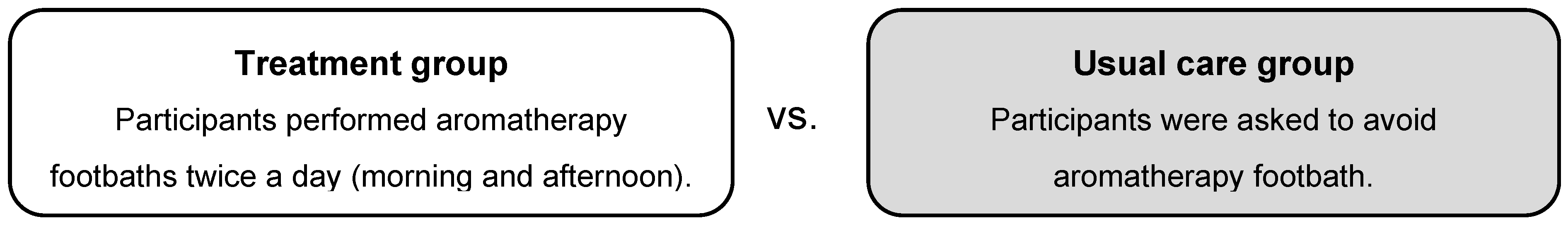

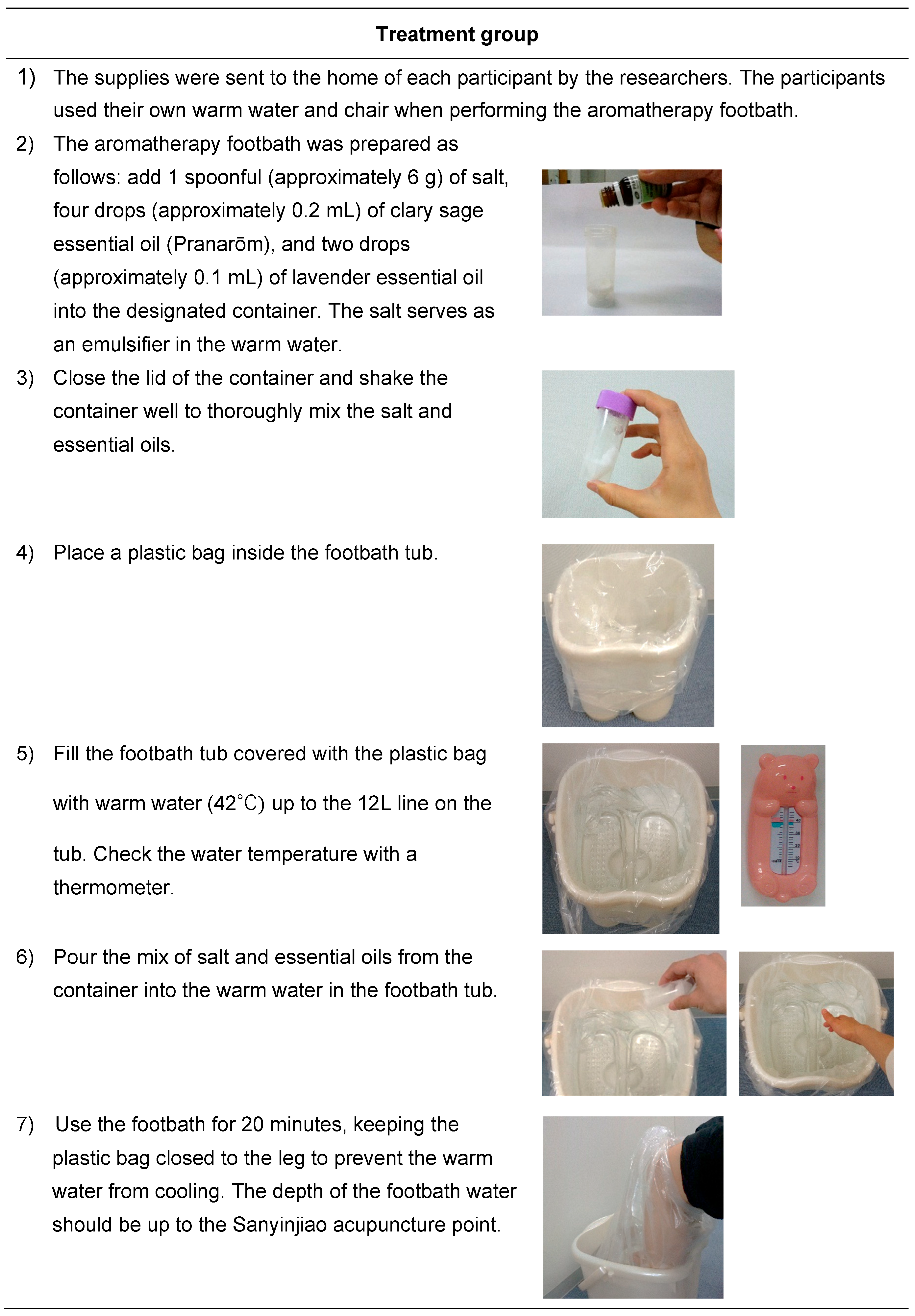

2.2.3. Intervention

2.2.4. Data Collection

2.2.5. Analysis

2.3. Investigation of Feasibility

2.3.1. Data Collection for Investigating Feasibility

2.3.2. Feasibility Evaluation

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Acceptability

3.1.1. Acceptability Among Pregnant Women

3.1.2. Acceptance Among Staff in the Setting Facility

3.2. Demand

3.3. Implementation

3.4. Practicality

3.5. Process

3.6. Resources

3.7. Management

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Definition of term pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 1139–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, E.M.; Gunnarsdottir, J.; Zoega, H.; Bjarnadottir, R.I.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Einarsdottir, K. Trends in labor induction indications: A 20-year population-based study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2022, 101, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Kelly, A.J.; Dowswell, T. Intravenous oxytocin alone for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD003246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.C.; Kucirka, L.; Chau, D.B.; Hadley, M.; Sheffield, J.S. Evidence-based protocol decreases time to vaginal delivery in elective inductions. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conell-Price, J.; Evans, J.B.; Hong, D.; Shafer, S.; Flood, P. The development and validation of a dynamic model to account for the progress of labor in the assessment of pain. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, C.; Gross, M.M.; Heusser, P.; Berger, B. Women’s perceptions of induction of labour outcomes: Results of an online-survey in Germany. Midwifery 2016, 35, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Johnson, P.J.; Attanasio, L.B.; Gjerdingen, D.K.; McGovern, P.M. Use of nonmedical methods of labor induction and pain management among U.S. women. Birth 2013, 40, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.; Blamey, C.; Ersser, S.J.; Lloyd, A.J.; Barnetson, L. The use of aromatherapy in intrapartum midwifery practice an observational study. Complement. Ther. Nurs. Midwifery 2000, 6, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münstedt, K.; Brenken, A.; Kalder, M. Clinical indications and perceived effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine in departments of obstetrics in Germany: A questionnaire study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 146, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, M.; Grabowska, C. Complementary therapy for induction of labour. Pract. Midwife 2013, 16, S16–S18. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M. Postdates pregnancy and complementary therapies. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2009, 15, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviani, M.; Maghbool, S.; Azima, S.; Tabaei, M.H. Comparison of the effect of aromatherapy with Jasminum officinale and Salvia officinale on pain severity and labor outcome in nulliparous women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2014, 19, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musil, A. Labor encouragement with essential oils. Midwifery Today Int. Midwife 2013, 107, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro, Y.; Takahata, K.; Shuo, T.; Shinohara, K.; Horiuchi, S. Changes in salivary oxytocin level of term pregnant women after aromatherapy footbath for spontaneous labor onset: A non-randomized experimental study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. Aromatherapy facts and fictions: A scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. Int. J. Neurosci. 2009, 119, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, Y.; Horiuchi, S.; Takahata, K.; Shuo, T.; Sawano, E.; Shinohara, K. Changes in salivary oxytocin after inhalation of clary sage essential oil scent in term-pregnant women: A feasibility pilot study. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarumi, W.; Shinohara, K. The Effects of essential oil on salivary oxytocin concentration in postmenopausal women. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahra, A.; Leila, M.S. Lavender aromatherapy massages in reducing labor pain and duration of labor: A randomized controlled trial. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilian, K.; Keramat, A. The effect of breathing technique with and without aromatherapy on the length of active phase and second stage of labour. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2013, 2, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour Lamadah, S. The effect of aromatherapy massage using lavender oil on the level of pain and anxiety during labour among primigravida women. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, M.; Zelkowitz, P.; Tulandi, T.; Hayton, B.; Feeley, N.; Carter, C.S.; Joseph, L.; Pournajafi-Nazarloo, H.; Ping, E.Y.; Abenhaim, H.; et al. Oxytocin in pregnancy and the postpartum: Relations to labor and its management. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.; Weller, A.; Zagoory-Sharon, O.; Levine, A. Evidence for a neuroendocrinological foundation of human affiliation: Plasma oxytocin levels across pregnancy and the postpartum period predict mother-infant bonding. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahata, K.; Horiuchi, S.; Tadokoro, Y.; Sawano, E.; Shinohara, K. Oxytocin levels in low-risk primiparas following breast stimulation for spontaneous onset of labor: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A.; PAFS Consensus Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, M.B.; Ghisi, G.L.M.; Oh, P.; Pereira, D.S.; Moreira, A.P.B.; Jansen, A.K.; Batalha, A.P.D.B.; Cândido, G.N.; Almeida, J.A.; Pereira, D.A.G.; et al. Feasibility of remote delivering an exercise and lifestyle education program for individuals living with prediabetes and diabetes in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbos, C.; Rummens, S.; Bogaerts, K.; Van Hoylandt, A.; Hoornaert, S.; Weyns, F.; Dubuisson, A.; Ceuppens, J.; Schuind, S.; Groen, J.L.; et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing conservative versus surgical treatment in patients with foot drop due to peroneal nerve entrapment: Results of an internal feasibility pilot study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matziorinis, A.M.; Flo, B.K.; Skouras, S.; Dahle, K.; Henriksen, A.; Hausmann, F.; Sudmann, T.T.; Gold, C.; Koelsch, S. A 12-month randomised pilot trial of the Alzheimer’s and music therapy study: A feasibility assessment of music therapy and physical activity in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefnagels, J.W.; Fischer, K.; Bos, R.A.T.; Driessens, M.H.E.; Meijer, S.L.A.; Schutgens, R.E.G.; Schrijvers, L.H. A feasibility study on two tailored interventions to improve adherence in adults with haemophilia. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, M.; Hemmingsson, H.; Boman, I.L.; Danielsson, H.; Jaarsma, T. Feasibility of an intervention for patients with cognitive impairment using an interactive digital calendar with mobile phone reminders (RemindMe) to improve the performance of activities in everyday life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.F.; Malmgren Fänge, A.; Rogmark, C.; Ekvall Hansson, E. Rehabilitation outcomes following hip fracture of home-based exercise interventions using a wearable device-A randomized controlled pilot and feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, C.K.; Smith, C.A.; Dahlen, H.; Bisits, A.; Schmied, V. Moxibustion for cephalic version: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.A.; Dodd, S.; Williamson, P.R. Design and analysis of pilot studies: Recommendations for good practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2024, 10, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadzki, P.; Alotaibi, A.; Ernst, E. Adverse effects of aromatherapy: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2012, 24, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisserand, R.; Young, R. Essential Oil Safety: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. In Churchill Livingstone, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, A.C.; Davis, L.L.; Kraemer, H.C. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Cohn, E.S. The distinctive features of a feasibility study: Objectives and guiding questions. OTJR 2015, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Lewin, S.; Thomas, K.J.; Young, B.; Adamson, J.; Jansen, Y.J.; Mills, N.; Moore, G.; Donovan, J.L. Maximising the impact of qualitative research in feasibility studies for randomised controlled trials: Guidance for researchers. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2015, 1, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, P.T.; Beattie, W.S.; Bryson, G.L.; Paul, J.E.; Yang, H. Effects of neuraxial blockade may be difficult to study using large randomized controlled trials: The PeriOperative Epidural Trial (POET) Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, J.; Kelly, A.J.; Thomas, J. Breast stimulation for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2005, CD003392. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Armour, M.; Dahlen, H.G. Acupuncture or acupressure for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD002962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibbritt, D.W.; Catling, C.J.; Adams, J.; Shaw, A.J.; Homer, C.S. The self-prescribed use of aromatherapy oils by pregnant women. Women Birth 2014, 27, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weijers, M.; Boumans, N.; van der Zwet, J.; Feron, F.; Bastiaenen, C. A feasibility Randomised Controlled Trial as a first step towards evaluating the effectiveness of a digital health dashboard in preventive child health care: A mixed methods approach. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Cooley, S.J. A feasibility study of the My Strengths Training for Life™ (MST4Life™) program for young people experiencing homelessness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauley, T.; Percival, R. Reducing post-dates induction numbers with post-dates complementary therapy clinics. Br. J. Midwifery 2014, 22, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, A.S.; Frisell, T.; Svensson, A.C.; Iliadou, A.N. Maternal and fetal genetic contributions to postterm birth: Familial clustering in a population-based sample of 475,429 Swedish births. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughey, A.B.; Stotland, N.E.; Washington, A.E.; Escobar, G.J. Who is at risk for prolonged and postterm pregnancy? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 200, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mälstam, E.; Asaba, E.; Åkesson, E.; Guidetti, S.; Patomella, A.H. The feasibility of make my day—A randomized controlled pilot trial of a stroke prevention program in primary healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaghi, N.; van Kruijsbergen, M.; Speckens, A.; Vilé, J.; Prins, J.; Kelders, S.; Kwakkenbos, L. Group, blended and individual, unguided online delivery of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with cancer: Feasibility uncontrolled trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e52338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feasibility Domain | Data Collected | Data Collection Timing | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability To what extent is the treatment judged as suitable, satisfying, or attractive to pregnant women and setting staff? | Satisfaction with the treatment Preference for conducting the treatment for future pregnancy Whether participants would recommend the treatment to pregnant women | After delivery | Interview with the participants in the treatment group |

| Sense of adaptation with the facility’s culture Advantages/disadvantages of conducting the intervention in the facility | Interview with the midwives of the facility | ||

| Demand To what extent is the treatment likely used? | Interest in and intention for conducting the treatment | Before randomization | Records from oral questions to the participants by researchers |

| Implementation To what extent can the treatment be successfully delivered to pregnant women? | Degree of execution | After delivery | Self-reported questionnaire from the participants in both groups |

| Success or failure of execution Resources needed to implement Factors affecting implementation ease or difficulty | Interview with the participants in the treatment group | ||

| Practicality To what extent can the treatment be carried out with pregnant women using existing means, resources, and circumstances and without outside intervention? | Ability of the treatment group to carry out the treatment Whether the treatment could be performed without supplies provided | After delivery | Interview with the participants in the treatment group |

| Financial costs of research execution | Records by researchers | ||

| Process Key to success | Research participation rate (within the recruited eligible women who consented to participate/recruited eligible women) | Before randomization | Records by researchers |

| Resources Time and resource problems | Follow-up rate | After delivery | Data from medical records by researchers and self-reported questionnaire from the participants in both groups |

| Appropriateness of the eligibility criteria for participants | Records by researchers | ||

| Understanding of documents including research explanation, instructions for the treatment, and questionnaire Time required to complete the questionnaire | Interview with the participants in the treatment group | ||

| Missing values or unintended responses in questionnaire | Self-reported questionnaire from the participants in both groups | ||

| Management Potential human and data management problems | Overload of the study execution for researchers Handling of research supplies Required assistance availability by facility Capturing data for pilot RCT using software | After delivery | Records by researchers |

| Facility willingness and capacity to collaborate Issues being raised in a facility | Interview with midwives of the facility |

| Treatment Group (n = 6) | Usual Care Group (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.3 (5.4) | 35.7 (3.9) |

| BMI before pregnancy (SD) | 22.2 (4.7) | 20.4 (1.4) |

| BMI at delivery (SD) | 26.0 (3.4) | 24.0 (1.3) |

| Multipara | 5 | 4 |

| History of labor induction | 0 | 0 |

| History of labor augmentation | 0 | 0 |

| History of post-term delivery | 0 | 0 |

| Maternal history of post-term delivery | ||

| None | 4 | 4 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| Unknow | 2 | 0 |

| Paternal history of post-term delivery | ||

| None | 3 | 3 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| Unknow | 3 | 1 |

| Country of origin: Japan | 6 | 4 |

| Treatment Group (n = 6) | Usual Care Group (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Labor induction (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Delivery week (SD) | 39.8 (0.3) | 40.1 (0.3) |

| Labor and delivery hours (SD) | 6.0 (4.0) | 3.3 (1.9) |

| Labor augmentation (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Delivery mode: spontaneous vaginal delivery (%) | 6 (100) | 4 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tadokoro, Y.; Takahata, K. Feasibility Study for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Aromatherapy Footbath for Stimulating Onset of Labor in Term Pregnant Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060950

Tadokoro Y, Takahata K. Feasibility Study for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Aromatherapy Footbath for Stimulating Onset of Labor in Term Pregnant Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060950

Chicago/Turabian StyleTadokoro, Yuriko, and Kaori Takahata. 2025. "Feasibility Study for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Aromatherapy Footbath for Stimulating Onset of Labor in Term Pregnant Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060950

APA StyleTadokoro, Y., & Takahata, K. (2025). Feasibility Study for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Aromatherapy Footbath for Stimulating Onset of Labor in Term Pregnant Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060950