Understanding the Parental Caregiving of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia: Discovering the Untold Story

Abstract

1. Introduction

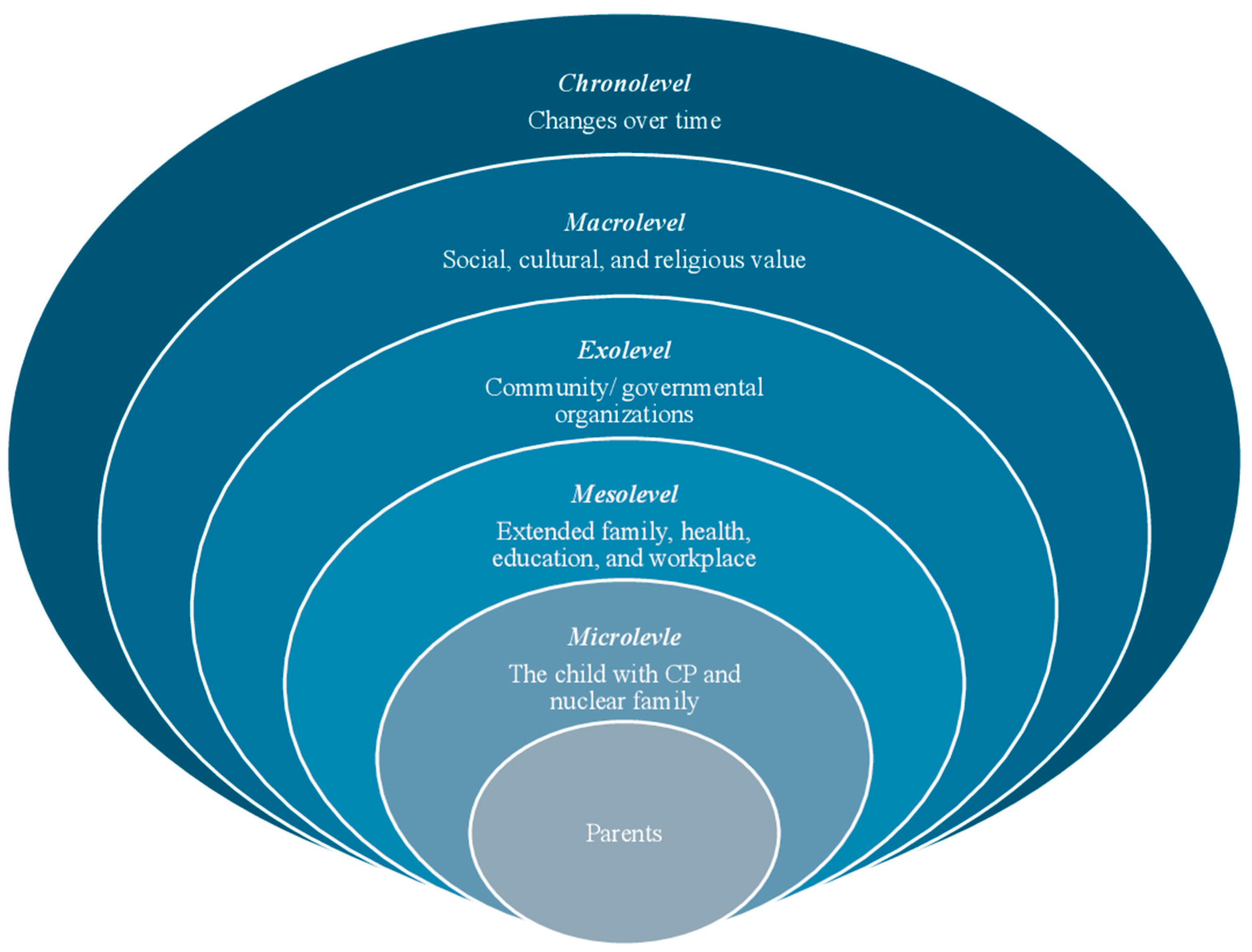

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Philosophical Assumptions

2.3. Positionality Statement

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Eligibility Criteria

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Study Quality

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Theme 1: The Complexity of the Caring Journey

My husband made the heartfelt decision to sell his car to help get our daughter a wonderful new wheelchair. As a result, I’ve put my master’s studies and work on hold to focus on supporting my son and meeting his needs. It’s a big change, but I truly believe it’s the right thing to do for our family needs.(M05)

I regularly impose a significant emotional burden on myself concerning my son’s condition. Despite my persistent efforts to provide him with the best possible support and care, I can’t shake the feeling that I am falling short of his needs. This thought frequently occupies my mind, intensifying my awareness of the heavy responsibilities I am not doing enough for him weighs heavily on my shoulders, often leading to moments of self-doubt and anxiety about my parenting capabilities.(M12)

My personality changed after having my child (child with CP). I am showing more sympathy.(F04)

My child is the key to my happiness in this life and for Jannah (Heaven).M10

There are many complex things in my life as a single mom for a child with a disability … like my psychological and financial states that suddenly improve because of my child. I didn’t notice them before, but now I feel it because of Allah then my child… before I couldn’t imagine that I would buy a car, but suddenly I bought one.M12

3.2.2. Theme 2: The Value of Family and External Support

I wish if my husband and my children could help me more…I wish my husband take care of my son’s appointment. My son does not like to go with his father because he just handles him to a therapist and does not sit with him in physiotherapy sessions… also, we don’t go to my family in-laws because they don’t ask about my son or let him feel welcoming or accepted.(M10)

“Thank Allah, we have increased in intimacy….my husband and I have become a united force. We tirelessly seek the best options for her, aiming to admit her to top-notch facilities and ensure she has all the necessary equipment. Overall, we’ve become diligent in our quest to provide for her.”(M05)

My brothers and in-laws ask about my child and pray for him… I would be happier if my sister-in-law could take my son and watch him for a short time, as we live close by, to allow me to relax and have some personal time.(M04)

As a community, we are indeed very cooperative, honestly. We have changed a lot; we are not like before… Now, people have come to like individuals like this (children with CP). They don’t leave them; they help them. For example, if we go to parks, people give my daughter a gift, and there are no looks or anything.(F01)

My son was playing, and some children came to play with him in the park. But they said: You are limping. He came to me and said: Mom, I’m not limping. I told him, ‘Sweetie, you’re not limping, but your leg just needs a little strengthening, and you need to continue to work on your exercise plans.(M10)

Since my son’s diagnosis, I have received little guidance on our (parents and the child) rights or how to navigate them. Most of what I have learned has come through my own research or the shared experiences of other mothers.(M03)

3.2.3. Theme 3: The Quality of Educational and Healthcare Services

While attending my daughter’s school, I observed a lack of accessibility features. This is particularly concerning as accessibility is important for all students, including those with disabilities. While the school has attempted to install accessible toilets for children with special needs, these facilities unfortunately do not meet my daughter’s specific needs.(M11)

I wish someone had informed me about the diagnosis sooner. As a premature baby, he had regular check-up appointments every month, yet no one has delivered a definitive diagnosis. This ongoing uncertainty is concerning and frustrating and has led my wife to explore other traditional ways…. we visited an old lady in (village) who specialized in herbal treatments.(F09)

During my son’s PT sessions, I often fall asleep on the couch because I sometimes come directly from work…. I’m present, observing and asking questions, but no one explains why certain exercises are done or which part of the body they target I wish there were educational courses for parents about physical therapy and exercises, and my boss gave me a flexible schedule.(M10)

I go to a private clinic in Riyadh twice every month (400 kilometres away from their city) with my wife and my child, as many good clinics are in Riyadh, and one session … I really feel embarrassed every time I ask for leave from my supervisor at my job because most of my son’s appointments are during work hours.(F07)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Recommendations for Community-Based Programming, Resources, and Policies

Due to the heavy curriculum and tightly packed schedule, my son’s educational needs and capabilities are often overlooked. Sometimes, my son would experience a muscle spasm at school, and neither his father nor the teachers knew how to respond, so they would call me.(M10)

When I came to my son’s appointment, I saw the healthy people occupying the parking space that is allotted to disabled people and their families, which can lead us to park in another spot and walk… when my son arrived at the clinic, he felt tired. Accessible parking spaces are essential for families with children with disabilities. It’s important to have clear policies in place to prevent misuse by others in the community.(M10)

“When everyone-family, community, government works together, we can build a society where all members, regardless of their abilities, can thrive and contribute meaningfully”(F08).

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mushta, S.M.; Khandaker, G.; Power, R.; Badawi, N. Cerebral Palsy in the Middle East: Epidemiology, Management, and Quality of Life. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, B.A.; Al-Amri, A.S.; Jawhari, A.A.; Sait, R.M.; Talb, R.Y. Prevalence, Types, and Outcomes of Cerebral Palsy at a Tertiary Center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e27716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almosallam, A.; Qureshi, A.Z.; Alzahrani, B.; AlSultan, S.; Alzubaidi, W.I.; Alsanad, A. Caregiver Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior Toward Care of Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Saudi Arabian Perspective. Healthcare 2024, 12, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, E.M.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Alghamdi, R.A.; Alghamdi, M.S.; Alzahrani, T.A. Level of Awareness and Attitude Toward Cerebral Palsy Among Parents in Al-Baha City, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e31791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.Z.; Tan, Y.H.; Yeo, T.H.; Teoh, O.H.; Min Ng, Z. Epidemiology and risk factors for sleep disturbances in children and youth with cerebral palsy: An ICF-based approach. Sleep Med. 2022, 96, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudebeck, S.R. The psychological experience of children with cerebral palsy. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 30, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-van Vuuren, J.; Lysaght, R.; Batorowicz, B.; Dawud, S.; Aldersey, H.M. Family Quality of Life and Support: Perceptions of Family Members of Children with Disabilities in Ethiopia. Disabilities 2021, 1, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.; Mehelay, S.; Phadke, S.; Macdonald, D.; Aldersey, H.; White, A.R.; Fakolade, A. Understanding the State of Research Evidence Involving Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy in the Arab Contexts: A Scoping Review. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 9, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhumaidi, K.A.; Alshwameen, M.O.; Alsayed, M.S.; Alqoaer, D.K.; Albalawi, R.S.; Alanzi, S.M.; Alharthe, A.F.; Abdulaziz Subayyil Alanazi, H. Quality of Life of Primary Caregivers of Children with Cerebral Palsy from a Family Perspective. Cureus 2023, 15, e49378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangkovan, I.T.; Shorey, S. Experiences and Needs of Parents Caring for Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, J. Activity limitation in children with cerebral palsy and parenting stress, depression, and self-esteem: A structural equation model. Pediatr. Int. 2020, 62, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmann, K.; Flibotte, J.; DeMauro, S.B.; Seitz, H. A Mixed Methods Analysis of Parental Perspectives on Diagnosis and Prognosis of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Graduates with Cerebral Palsy. J. Child Neurol. 2020, 35, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugała, B.; Penar-Zadarko, B.; Pięciak-Kotlarz, D.; Wardak, K.; Lewicka-Chomont, A.; Futyma-Ziaja, M.; Opara, J. Assessment of Anxiety and Depression in Polish Primary Parental Caregivers of Children with Cerebral Palsy Compared to a Control Group, as well as Identification of Selected Predictors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwhaibi, R.M.; Omer, A.B.; Khan, R. Factors Affecting Mothers’ Adherence to Home Exercise Programs Designed for Their Children with Cerebral Palsy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; El Awady, S.; El Afandy, A. Mothers’ Perception toward their Children who Suffering from Cerebral Palsy at the Pediatric Outpatient in Minia University Hospital. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2023, 9, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, M.S.; AL-Rawajfah, O.M. Lived experiences of Jordanian mothers caring for a child with disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2723–2733. Available online: https://www-tandfonline-com.proxy.queensu.ca/doi/abs/10.1080/09638288.2017.1354233 (accessed on 7 November 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasscock, R. A phenomenological study of the experience of being a mother of a child with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Nurs. 2000, 26, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonnell, C.; Luke, N.; Short, S.E. Happy Moms, Happier Dads: Gendered Caregiving and Parents’ Affect. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 2553–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayles, E.; Harvey, D.; Plummer, D.; Jones, A. Parents’ Experiences of Health Care for Their Children with Cerebral Palsy. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; Imrie, H.; Brouwer, E.; Clutton, S.; Evans, J.; Russell, D.; Bartlett, D. “If I Knew Then What I Know Now”: Parents’ Reflections on Raising a Child with Cerebral Palsy. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2011, 31, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, B.; Kerr, C.; Shields, N.; Adair, B.; Imms, C. Steering towards collaborative assessment: A qualitative study of parents’ experiences of evidence-based assessment practices for their child with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.; Pereira, A.; Oliveira, A.; Lopes, S.; Nunes, A.R.; Zanatta, C.; Rosário, P. Parenting in Cerebral Palsy: Understanding the Perceived Challenges and Needs Faced by Parents of Elementary School Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheikh, A.S.; Alqurashi, A.M. Disabled Future in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 16, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh Al Mutair, A.; Plummer, V.; Paul O’Brien, A.; Clerehan, R. Providing culturally congruent care for Saudi patients and their families. Contemp. Nurse 2014, 46, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, F.; Tedla, J.S.; Sangadala, D.R.; Reddy, R.S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Gular, K.; Dixit, S.; Kakaraparthi, V.N.; Nayak, A.; Mohammed Aldarami, M.A.; et al. Quality of Life among Caregivers of Children with Disabilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. J. Disabil. Res. 2023, 2, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algood, C.L.; Harris, C.; Hong, J.S. Parenting Success and Challenges for Families of Children with Disabilities: An Ecological Systems Analysis. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2013, 23, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamón, N.; Nieto, R.; Pousada, M.; Redolar, D.; Muñoz, E.; Hernández, E.; Boixadós, M.; Gómez-Zúñiga, B. Quality of life and mental health among parents of children with cerebral palsy: The influence of self-efficacy and coping strategies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadivelan, K.; Sekar, P.; Sruthi, S.S.; Gopichandran, V. Burden of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: An intersectional analysis of gender, poverty, stigma, and public policy. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterman, R.; Leitner, Y.; Yifat, R.; Gilutz, G.; Levi-Hakeini, O.; Bitchonsky, O.; Rosenbaum, P.; Harel, S. Cerebral palsyg-long-term medical, functional, educational, and psychosocial outcomes. J. Child Neurol. 2010, 25, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambi, J.M.; Mandizvidza, C.; Chiwaridzo, M.; Nhunzvi, C.; Tadyanemhandu, C. Does an educational workshop have an impact on caregivers’ levels of knowledge about cerebral palsy? A comparative, descriptive cross-sectional survey of Zimbabwean caregivers. Malawi Med. J. 2017, 28, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. Int. Encycl. Educ. 1994, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reporting guidelines for qualitative research: A values-based approach. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2025, 22, 399–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilanowski, J.F. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 295–297. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wagr20 (accessed on 21 March 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahayneh1, M.; Humayra, S.; Fall, A.A.; Rosland, H.; Amro, A.; Mohammed, A.; Latiff Mohamed, A. Factors Affecting Mother’s Adherence towards Cerebral Palsy Home Exercise Program among Children at Hebron and Bethlehem, Palestine. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 12, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Mccallum, J.; Howes, D. Defining Exploratory-Descriptive Qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. J. Nurs. Health Care 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bassil, K.; Zabkiewicz, D. Health Research Methods: A Canadian Perspective; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292158938_Qualitative_Health_Research (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Levers, M.J.D. Philosophical Paradigms, Grounded Theory, and Perspectives on Emergence. Sage Open. 2013, 3, 2158244013517243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwankhong, D.; Liamputtong, P. Cultural Insiders and Research Fieldwork. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 1609406915621404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies (information power). Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y (accessed on 13 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clark, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–376. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, O.; Fakolade, A.; Cardwell, K.; Pilutti, L.A. A continuum of languishing to flourishing: Exploring experiences of psychological resilience in multiple sclerosis family caregivers. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Heal. Well-Being 2022, 17, 2135480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhouse, L. An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development; Heinemann: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, C. “Critical friends”, feminism and integrity: A reflection on the use of critical friends as a research tool to support researcher integrity and reflexivity in qualitative research studies. Women Welf. Educ. 2011, 10, 1–14. Available online: https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/items/4f5eeacb-4996-4b56-a809-33841337e124 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Tracy, S.J.; Hinrichs, M.M. Big Tent Criteria for Qualitative Quality. Int. Encycl. Commun. Res. Methods 2017, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Inquiry Qualitative Quality: Eight “‘Big-Tent’” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Madi, S.; Mandy, A.; Aranda, K. The Perception of Disability Among Mothers Living with a Child with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, E.H.; Za Ong, L.; Omar, I.A.; Bekhet, A.K.; Najeeb, J. Experiences of Muslim Mothers of Children with Disabilities: A Qualitative Study. J. Disabil. Relig. 2022, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.J. Paid to Care: The Origins and Effects of Care Leave Policies in Western Europe. Soc. Politics Int. Stud. Gend. State Society 2003, 10, 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C.; Bull, C.; Callander, E.J. Income support for parents of children with chronic conditions and disability: Where do we draw the line? A policy review. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brągiel, J.; Kaniok, P.E. Demographic variables and fathers’ involvement with their child with disabilities. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2014, 14, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, A.; Hindi, T.N. Exploring Fathers’ Perspectives on Family-Centered Services for Families of Children with Disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 124, 104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.A.; Hilario, A.; Matawaran, M.a.E.; Reyes, I.N.; Valero, L.M.; Paez, A.T. Unseen Struggles on the Financial Challenges Faced by Single Parents. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2024, VIII, 3466–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyzar, K.B.; Turnbull, A.P.; Summers, J.A.; GFmez, V.A. The Relationship of Family Support to Family Outcomes: A Synthesis of Key Findings from Research on Severe Disability. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, I.; Tareen, A.; Davidson, L.L.; Rahman, A. Community management of intellectual disabilities in Pakistan: A mixed methods study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mok, D.; Leenen, L. Transformation of health care and the new model of care in Saudi Arabia: Kingdom’s Vision 2030. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeglinsky, I.; Autti-Rämö, I.; Brogren Carlberg, E.; Jeglinsky, I. Two sides of the mirror: Parents’ and service providers’ view on the family-centredness of care for children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, L. Perceived benefits experienced in support groups for Chinese families of children with disabilities. Early Child Dev. Care 2010, 180, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.N.; Alharbi, A.; Albalwi, A.; Alatawi, S.; Algamdi, M.; Alshahrani, A.; Al Bakri, B.; Almasri, N. Characteristics of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Their Utilization of Services in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Yildiz, Y. Special Education Teacher-Training Programs in the United States and Turkey: Educational Policies and Practices and Their Repercussions on the Supply and Demand for Special Education Teachers in Turkey. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2015, 24, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil-Sztramko, S.E.; Dobbins, M.; Williams, A. Evaluation of a Knowledge Mobilization Campaign to Promote Support for Working Caregivers in Canada: Quantitative Evaluation. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e44226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.L.; Shlobin, N.A.; Winterhalter, E.; Lam, S.K.; Raskin, J.S. Gaps in transitional care to adulthood for patients with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2023, 39, 3083–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrossin, J.; Lach, L.; McGrath, P. Content analysis of parent training programs for children with neurodisabilities and mental health or behavioral problems: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRovere, K.L.; Tang, Y.; Li, K.; Wadhwani, N.; Zhang, B.; Tasker, R.C.; Yang, G. Effectiveness of Training Programs for Reducing Adverse Psychological Outcomes in Parents of Children with Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapulanga, M.; Dlungwane, T. Physical rehabilitation delivery by community health workers: Views of the users and caregivers. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2025, 17, 9. Available online: https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/4852/8195 (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dambi, J.M.; Jelsma, J. The Impact of Hospital-Based and Community Based Models of Cerebral Palsy Rehabilitation: A Quasi-experimental Study. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 1–10. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/301 (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chitiyo, M.; Muwana, F.C. Positive Developments in Special Education in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Int. J. Whole Sch. 2018, 14, 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Adjanku, J.K. Barriers to Access and Enrollment for Children with Disabilities in Pilot Inclusive Schools in Bole District in Ghana. Soc. Educ. Res. 2020, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Parents (caregivers) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 6 (50) |

| Male | 6 (50) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 11 (91.7) |

| Separated | 1 (8.3) |

| Level of education | |

| High school or less | 7 (58.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 (8.3) |

| Monthly family income (Saudi riyals (SAR)) | |

| <6000 | 6 (50) |

| ≥6000 | 6 (50) |

| Children with CP (care-recipients) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 4 (33) |

| Male | 8 (67) |

| CP type | |

| Hemiplegia | 1 (8.3) |

| Diplegia | 7 (58.3) |

| Quadriplegia | 4 (33.4) |

| Motor skill | |

| GMFCS 1 II | 5 (41.67) |

| GMFCS IV | 3 (25) |

| GMFCS V | 4 (33.33) |

| Mean (SD 2) | |

| Age of parents, years | 45 (11) |

| Age of children, years | 8 (4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqahtani, A.; Sahely, A.; Aldersey, H.M.; Finlayson, M.; Macdonald, D.; Fakolade, A. Understanding the Parental Caregiving of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia: Discovering the Untold Story. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060946

Alqahtani A, Sahely A, Aldersey HM, Finlayson M, Macdonald D, Fakolade A. Understanding the Parental Caregiving of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia: Discovering the Untold Story. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060946

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqahtani, Ashwaq, Ahmad Sahely, Heather M. Aldersey, Marcia Finlayson, Danielle Macdonald, and Afolasade Fakolade. 2025. "Understanding the Parental Caregiving of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia: Discovering the Untold Story" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060946

APA StyleAlqahtani, A., Sahely, A., Aldersey, H. M., Finlayson, M., Macdonald, D., & Fakolade, A. (2025). Understanding the Parental Caregiving of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia: Discovering the Untold Story. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060946