Parents’ Perceptions Regarding Needs and Readiness for Tele-Practice Implementation Within a Public Health System for the Identification and Rehabilitation of Children with Hearing and Speech–Language Disorders in South India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Study Site

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Participants

Parents of Children Under Six Years of Age

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.4.1. Qualitative Study—Guidelines

2.4.2. For Quantitative Study—Survey Questionnaire

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Qualitative Study

2.5.2. For Quantitative Study

2.6. Data Analysis

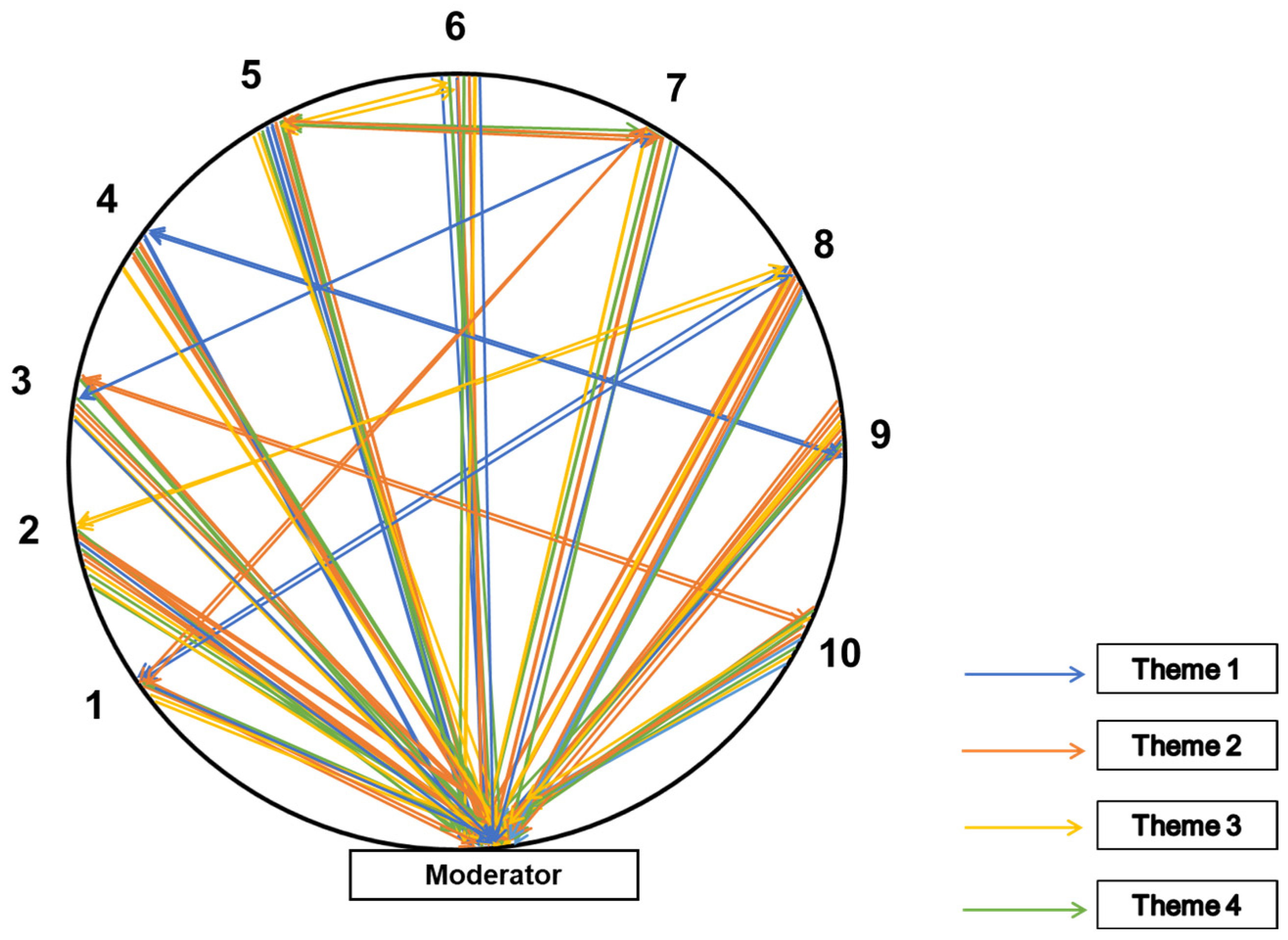

2.6.1. For Qualitative Study

2.6.2. Quantitative Study

3. Results

3.1. Participant Description

Parents of Children (with CwDs and CwnkDs)

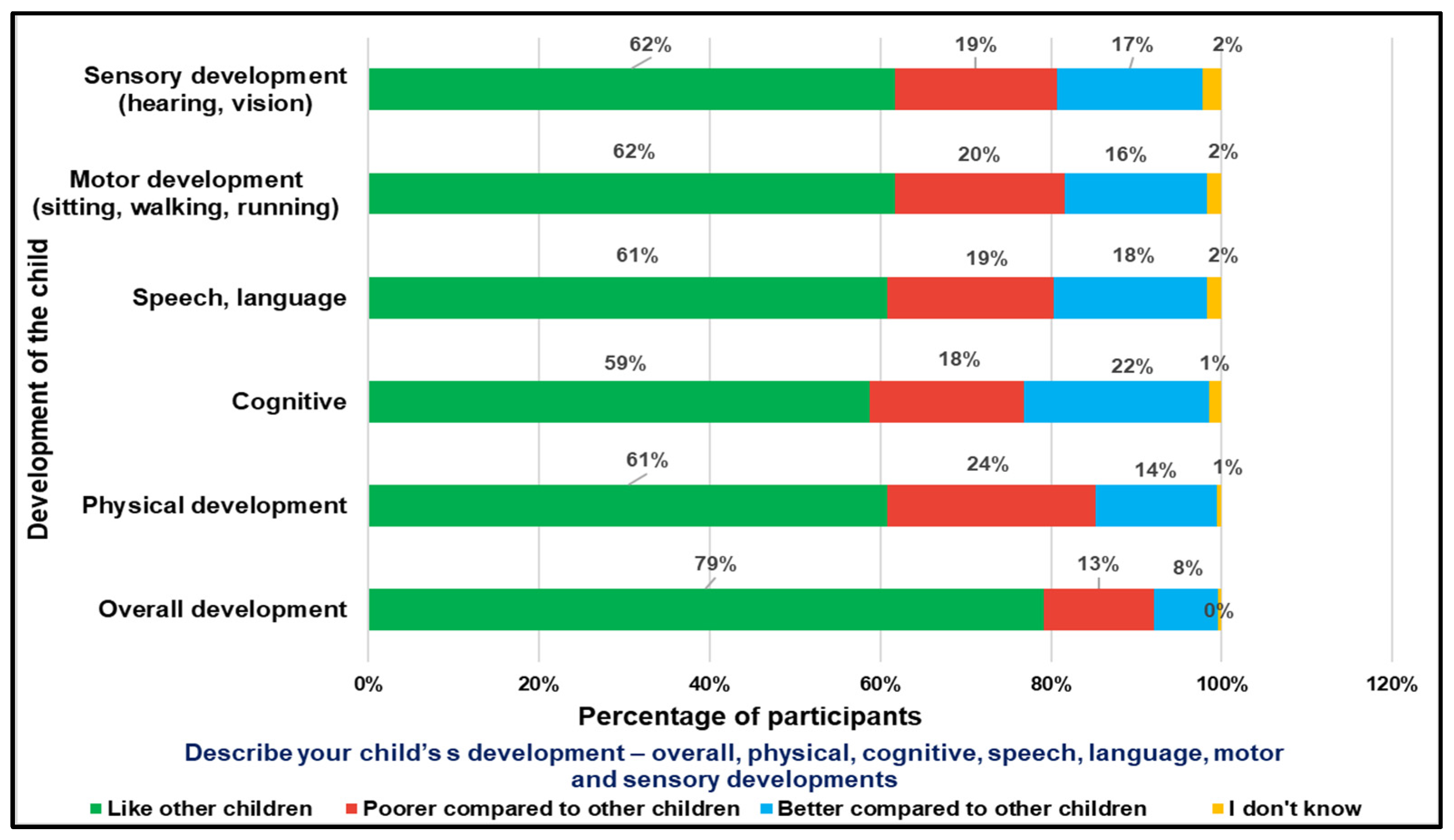

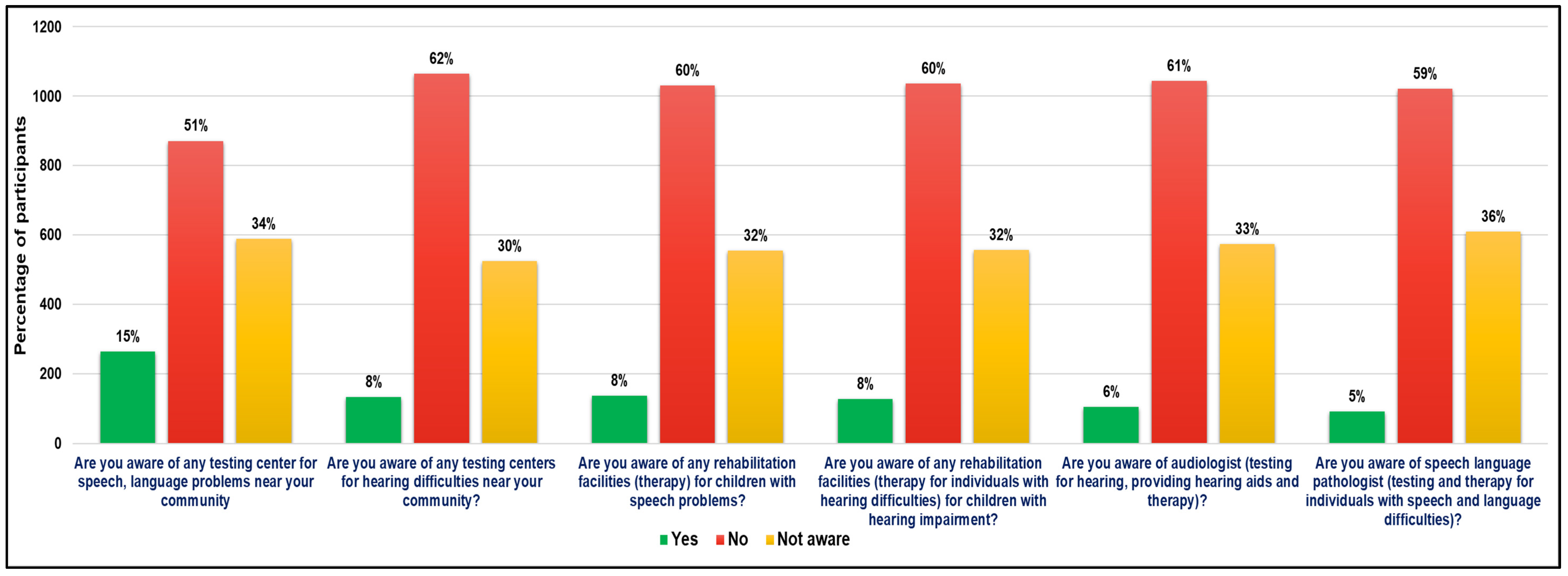

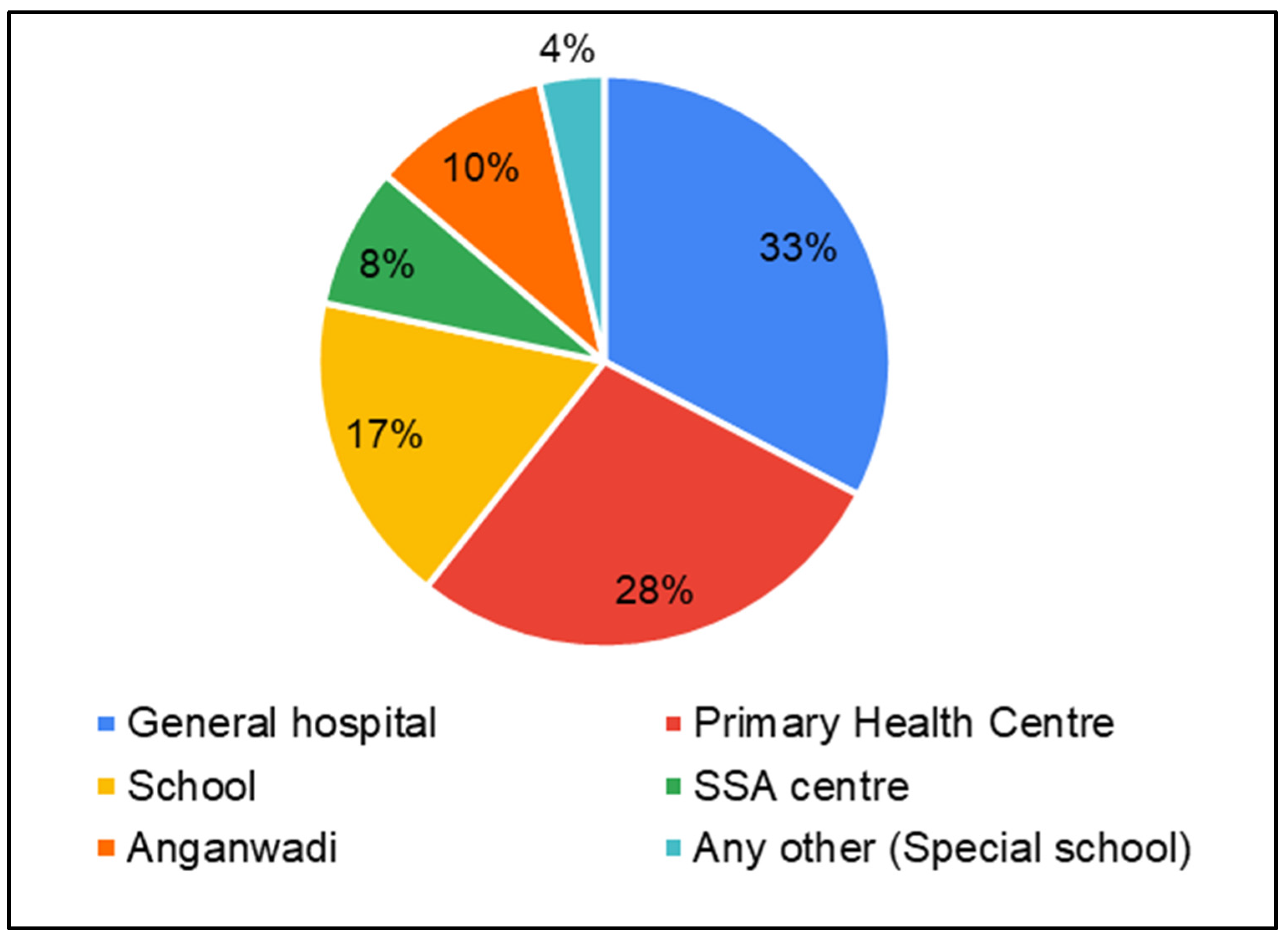

3.2. Perceptions of Parents of CwDs and Parents of CwnkDs Regarding Their Need for Audiology and Speech–Language Pathology Services and Their Readiness to Accept and Adopt Tele-Practice-Based Services

3.2.1. Need for Tele-Practice

“There are no testing facilities in the public sector in Ariyalur. We have to go to Thanjavur Trichy, Pondicherry”(Mothers of CwDs, FGDs).

“Special educators provide speech therapy and not speech therapists”(Fathers of CwDs, FGDs).

“If the facilities are provided nearby home, then it’s better”(Mothers of CwDs, FGDs).

“As there is a greater number of children in need of service, the bigger organization should help them out. The help needed are specialists. Currently having financial issues as a daily wage laborer”(Fathers of CwDs, FGDs).

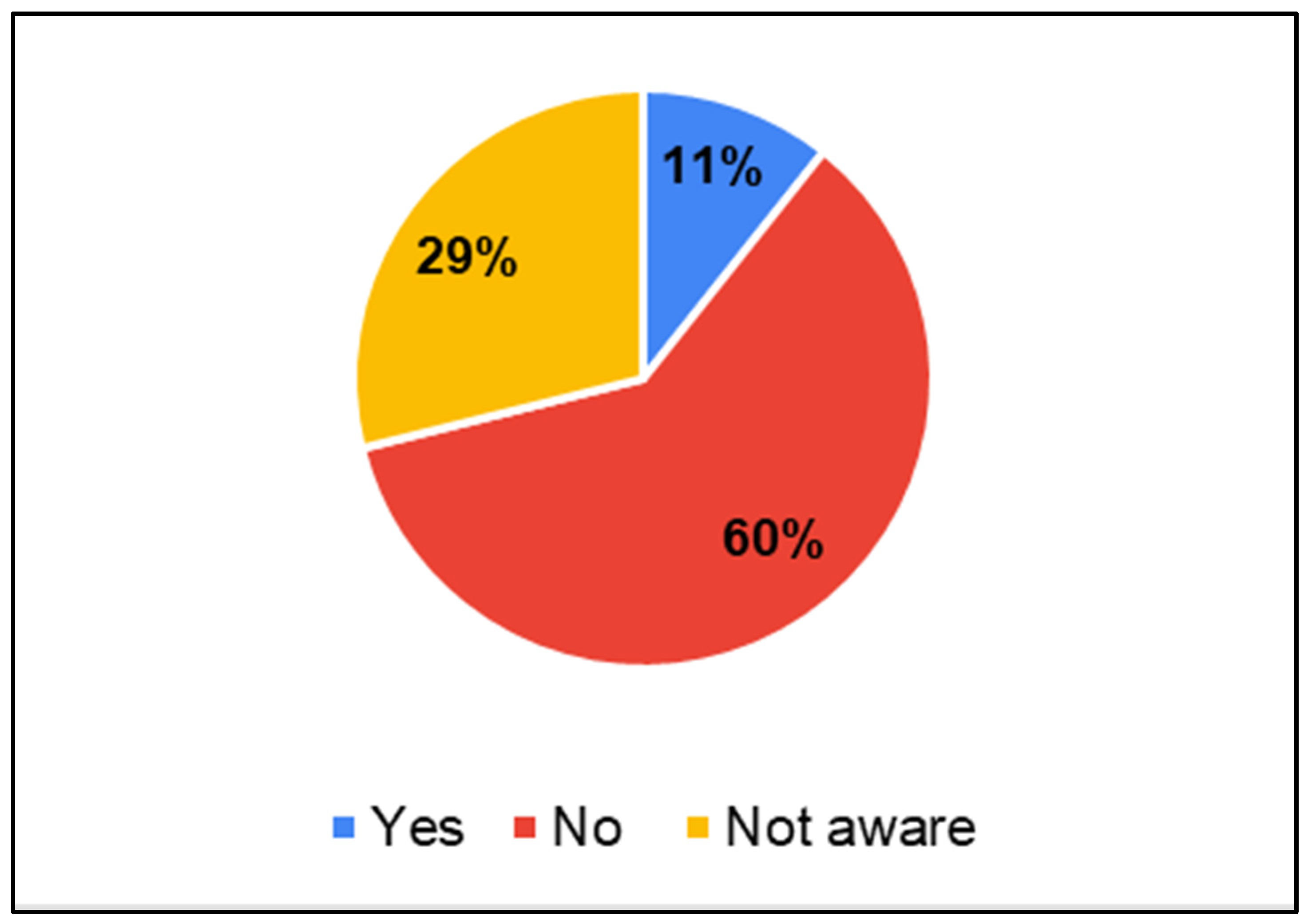

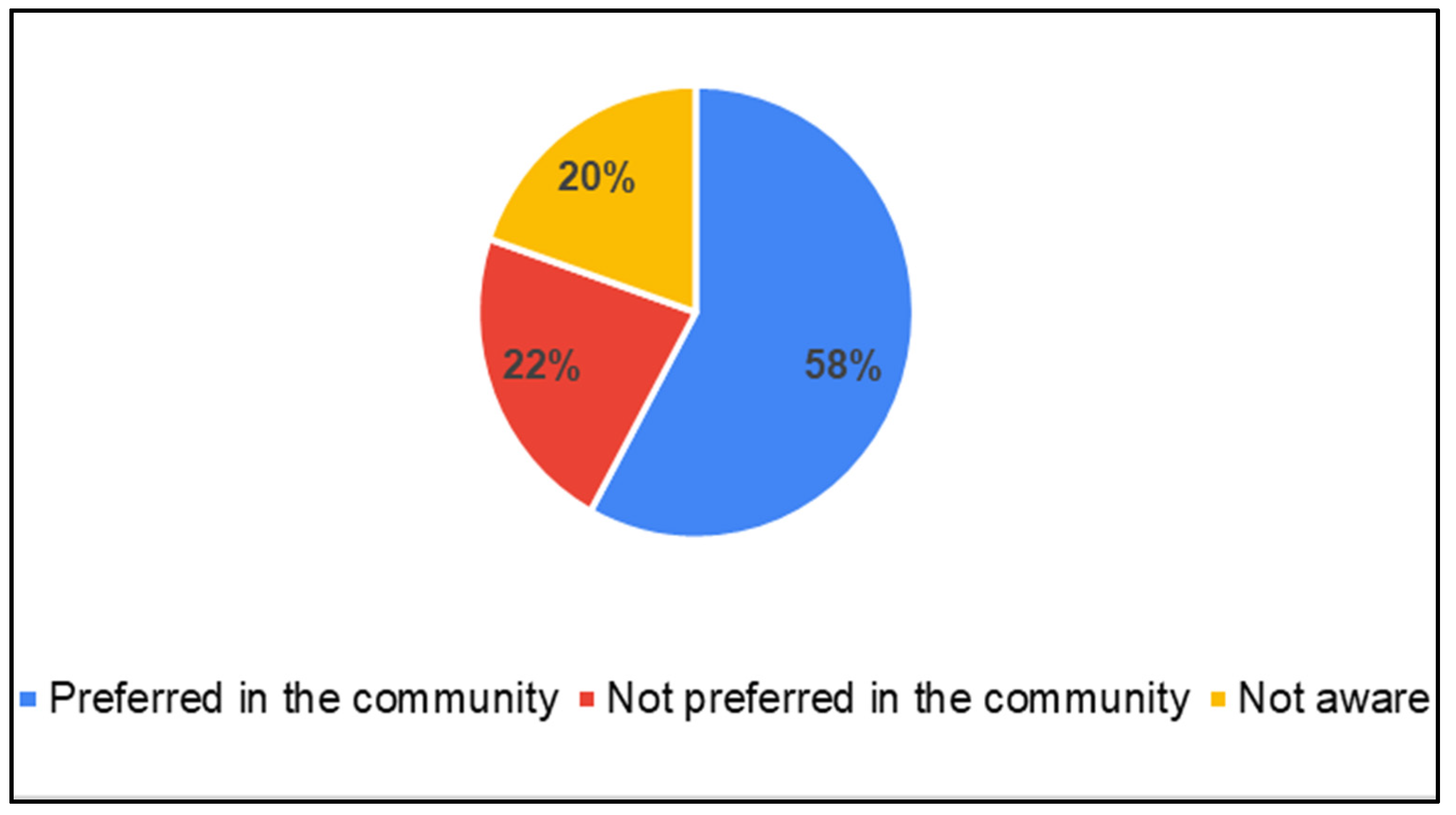

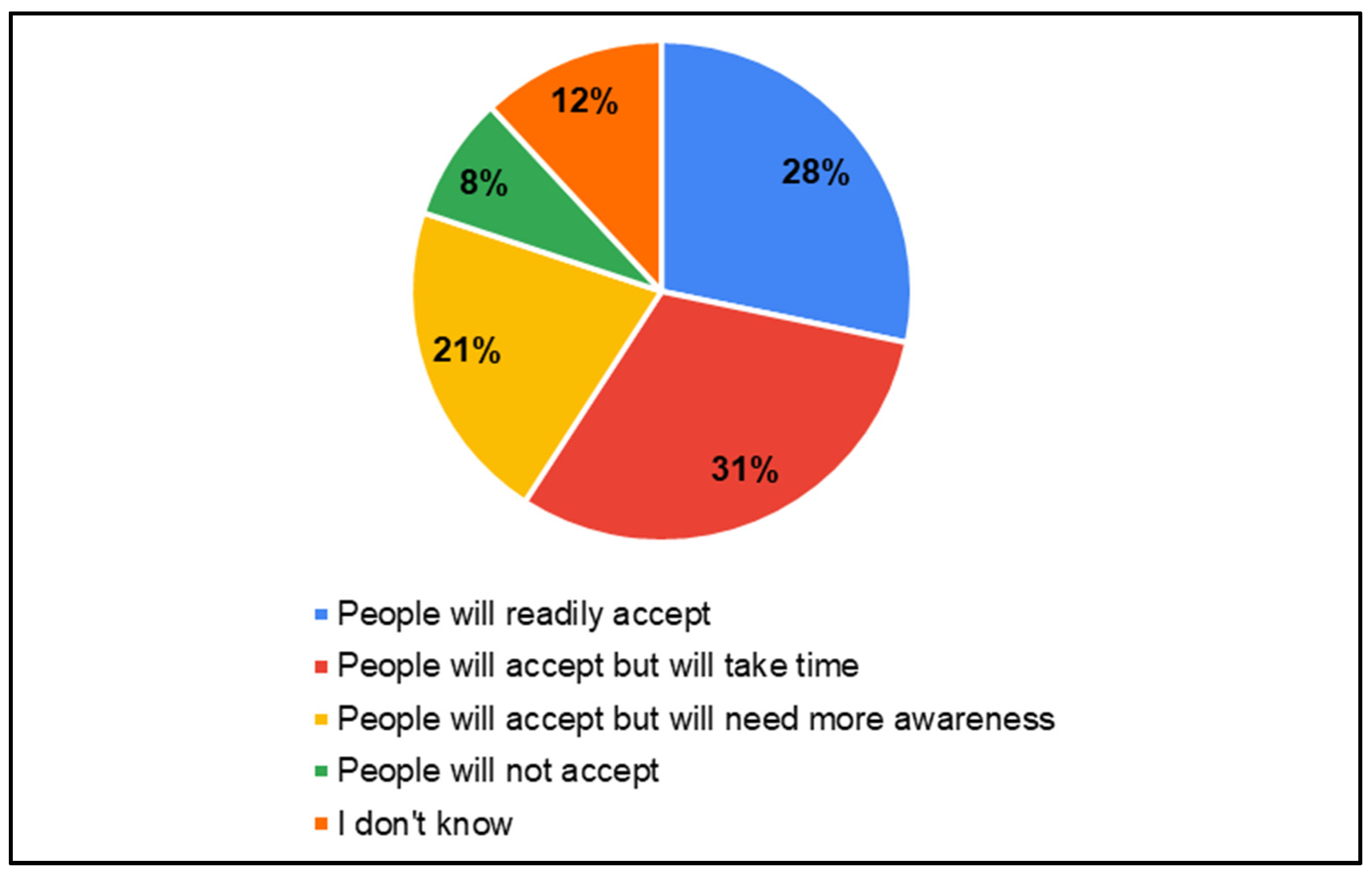

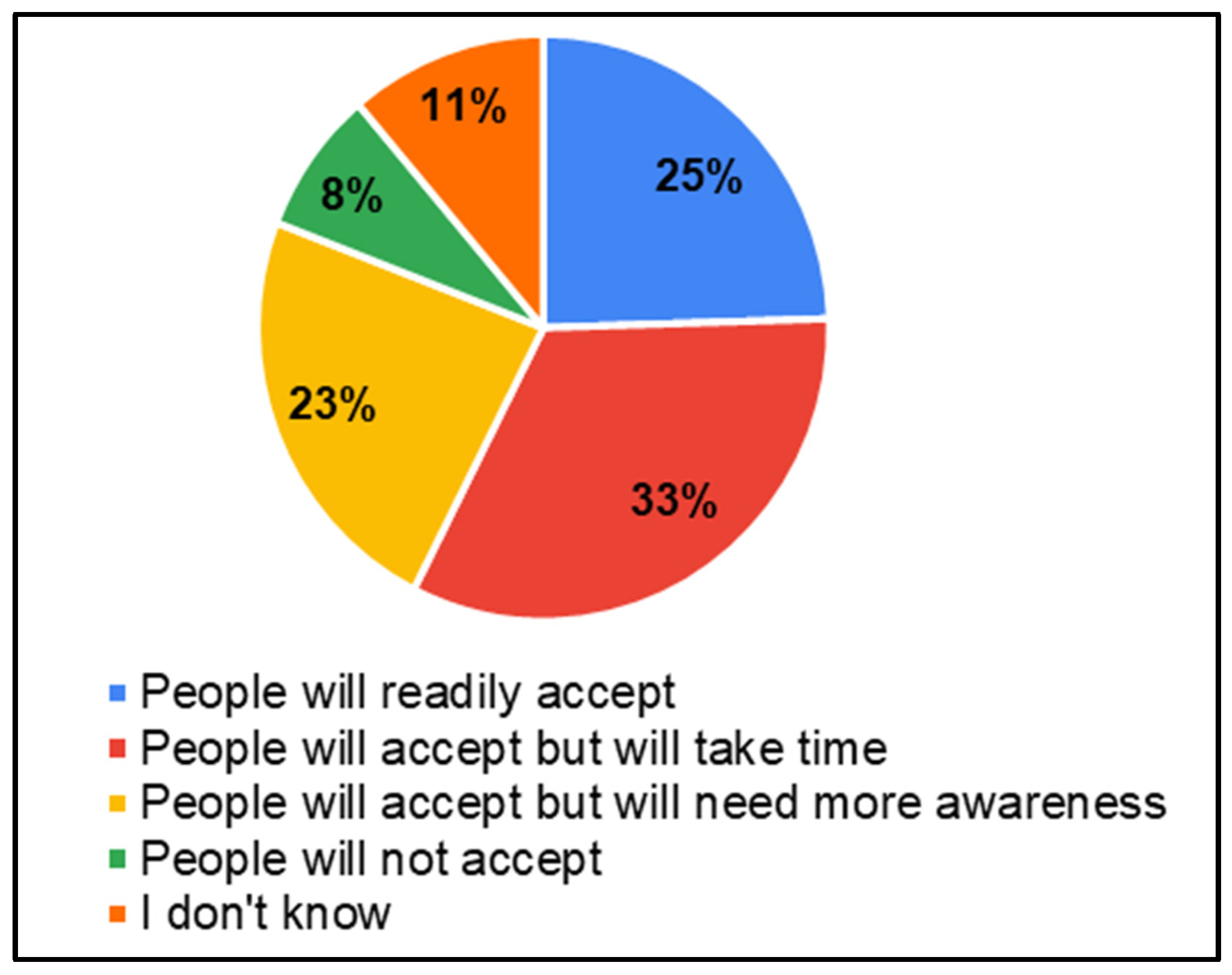

3.2.2. Readiness to Accept and Adopt Tele-Practice Services

“At first, you can do it (speech therapy) in person and later you can do it through a laptop. Which makes the people trust you”(Fathers of CwDs, SSIs).

“In Perambalur, most of them have smart phones for the purpose of studying (for children). Few of them have button phones (old model)(Mothers of CwDs, FGDs).

“Nurses (Village health nurse) can be trained to do screening”(Mothers of CwDs, FGDs).

“Anganwadi teachers can be trained for screening to reach all the children in the block”(Fathers of CwDs, SSIs).

“Village-wise service should be provided. With the help of a vehicle (mobile therapy unit). If the van is placed nearby then it will be beneficial as it’s difficult to carry the child to far places”(Fathers of CwDs, SSIs).

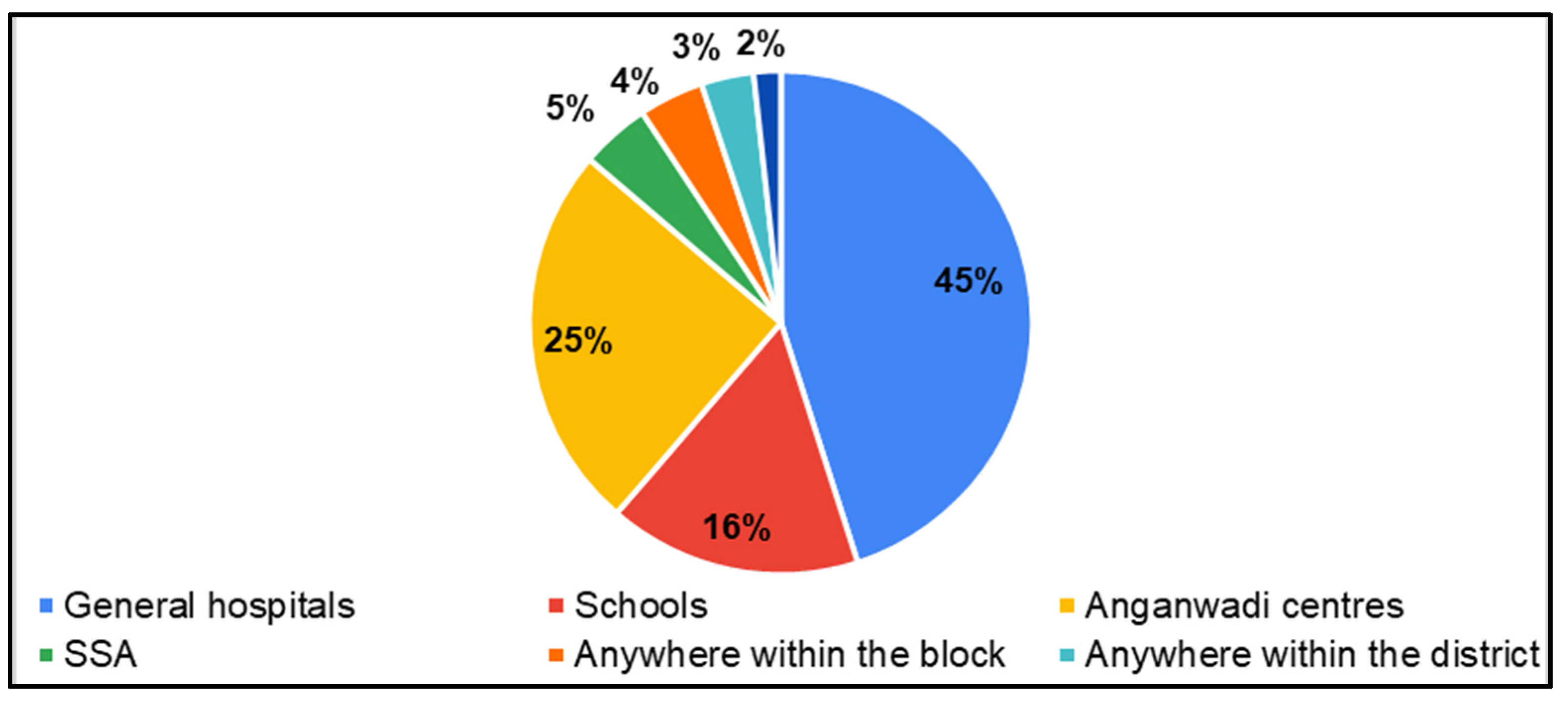

“Services can be provided in school so everyone will come. GH, PHC and Panchayat are the common places for everyone to come”(Fathers of CwDs, SSIs).

“Good awareness should be provided for the person with disability about the quality of service. Specialists should be available for differently abled people. If the service is provided then it will be helpful”(Fathers of CwDs, SSIs).

“Services can be conducted in the school block-wise”(Mothers of CwDs, FGDs).

4. Discussion

4.1. Need for Diagnostic and Rehabilitation Services for Hearing, Speech and Language Disorders

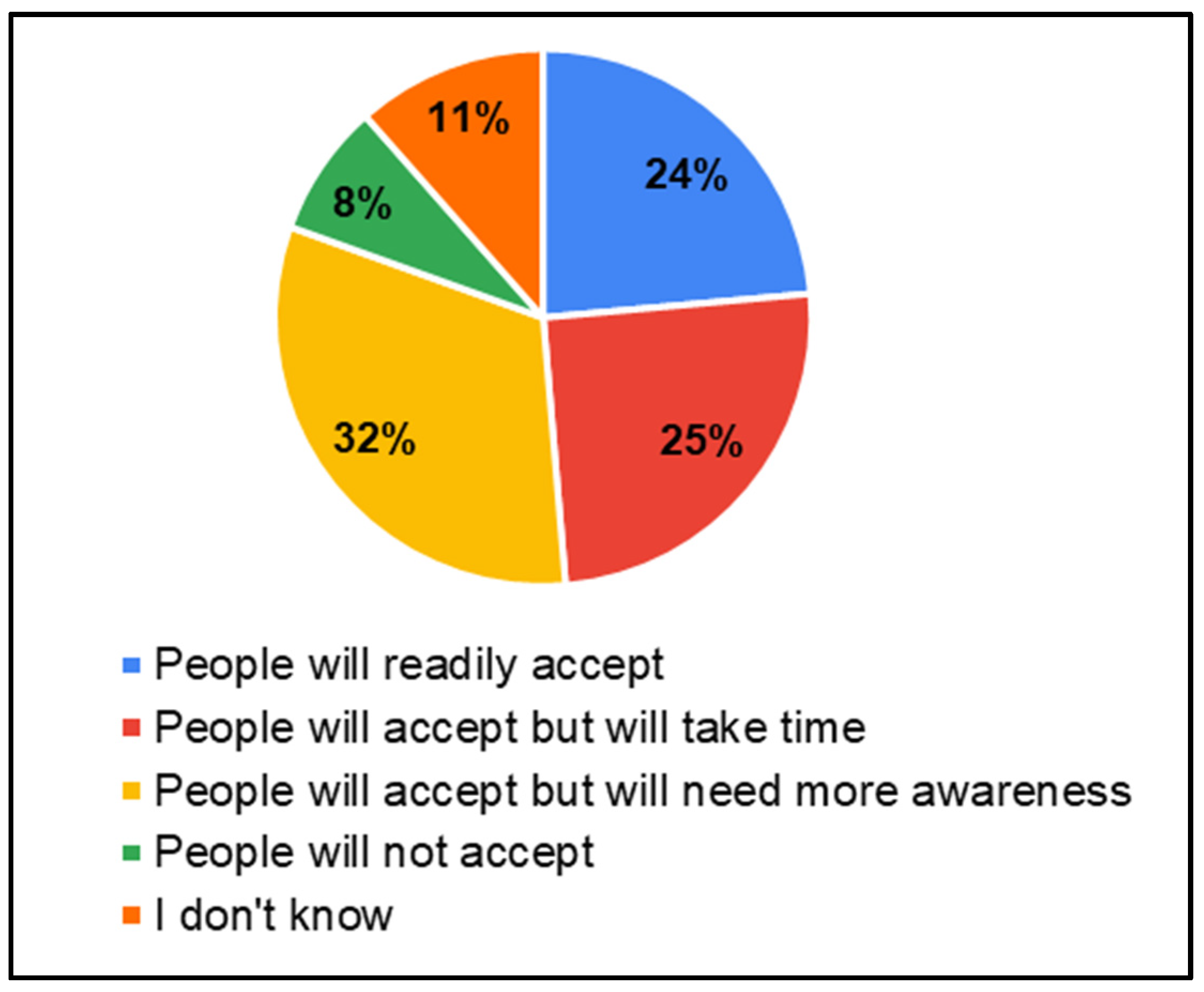

4.2. Readiness to Accept and Adopt Tele-Practice-Based Diagnostic and Rehabilitation Services for Hearing, Speech and Language Disorders

5. Conclusions

Study Outcomes

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| SSI | Semi-Structured Interview |

| CwDs | Children with Disabilities |

| CwnkDs | Children with no known Disabilities |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| EDC | Early Diagnostic Centre |

| GH | General Hospital |

| DDAW | District Differently Abled Welfare |

| EIC | Early Intervention Centre |

| ASLP | Audiologist and Speech–Language Pathologist |

| SSA | Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan |

| VHN | Village Health Nurse |

| DEIC | District Early Intervention Centre |

References

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. 2023. Children with Disabilities. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-disability/overview/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20CRPD%2C%20children,society%20on%20an%20equal%20basis%E2%80%9D (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- NFHS-5 (2019–21). Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR375/FR375.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Parab, S.R.; Khan, M.M.; Kulkarni, S.; Ghaisas, V.; Kulkarni, P. Neonatal screening for prevalence of hearing impairment in rural areas. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 70, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Wright, S.M.; Smythe, T.; Khetani, M.A.; Moreno-Angarita, M.; Gulati, S.; Brinkman, S.A.; Almasri, N.A.; Figueiredo, M.; Giudici, L.B.; et al. Early childhood development strategy for the world’s children with disabilities. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1390107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubula, L.; Dardzińska, N.; Dorobisz, K. Evaluation of hearing screening in newborns in Poland. Pediatr. Pol.-Pol. J. Paediatr. 2022, 97, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- States and Union Territories. Available online: https://knowindia.india.gov.in/states-uts/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Population Census. Available online: https://www.census2011.co.in/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Selvaraj, S.; Karan, A.K.; Srivastava, S.; Bhan, N.; Mukhopadhyay, I. India Health System Review; World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia: New Delhi, India, 2022; ISBN 9789290229049. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.K. Early identification of hearing loss and centralized newborn hearing screening facility-the Cochin experience. Indian Pediatr. 2011, 48, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Joy, J.M. Parent’s Perception and Expectations from Cochlear Implants: Insights from a Government-Funded Cochlear Implants Program in Kerala. J. Indian Speech Lang. Hear. Assoc. 2021, 35, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.B.; Bollapalli, V.R.; Saxena, U.; Mohanty, P.; Shora, S.; Kumar, S.R.; Shora, S. Cultural adaptation and translation of PEACH scale in Telugu language: Applicability in assessing auditory and communication skills of children with cochlear implant. Clin. Arch. Commun. Disord. 2020, 5, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Raghunath, D.; Dixit, D.S.; Bansal, D.S.B.; Patidar, D.A. A cross-sectional study to evaluate the functioning and infrastructure of DEIC, and client satisfaction Ujjain and Indore districts established under RBSK. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2016, 15, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshbabu, B.; Kumaravel, K.S.; Balaji, J.; Sathya, P.; Shobia, N. Health conditions screened by the 4Ds approach in a District Early Intervention Centre (DEIC) under Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) program. Pediatr. Oncall J. 2019, 16, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Workforce Data: 2022 ASHA-Certified Audiologist- and SLP-to-Population Ratios. 2023. Available online: https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/audiologist-and-slp-to-population-ratios-report.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Debsarma, D. Exploring the strategies for upgrading the rural unqualified health practitioners in West Bengal, India: A knowledge, attitude and practices assessment-based approach. Health Policy OPEN 2022, 3, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faster, M.I.; Growth, S. Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017); SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2013. Available online: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-08/12fyp_vol1.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Mohan, H.S.; Anjum, A.; Rao, P.K. A survey of telepractice in speech-language pathology and audiology in India. Int. J. Telerehabilit. 2017, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Fan, C.; Chen, B.; Fan, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Ma, Q.; He, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, J. Telemedicine is becoming an increasingly popular way to resolve the unequal distribution of healthcare resources: Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 916303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogourtsova, T.; Boychuck, Z.; O’Donnell, M.; Ahmed, S.; Osman, G.; Majnemer, A. Telerehabilitation for children and youth with developmental disabilities and their families: A systematic review. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2023, 43, 129–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akulwar-Tajane, I.; Bhatt, G.D. Telerehabilitation: An alternative service delivery model for pediatric neurorehabilitation services at a tertiary care center in India. Int. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 9, S4. [Google Scholar]

- Camden, C.; Pratte, G.; Fallon, F.; Couture, M.; Berbari, J.; Tousignant, M. Diversity of practices in telerehabilitation for children with disabilities and effective intervention characteristics: Results from a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 3424–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, V.; Shankar, V.; Kumar, S. Implementation factors influencing the sustained provision of tele-audiology services: Insights from a combined methodology of scoping review and qualitative semistructured interviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V.; Ramkumar, V.; Kumar, S. Understanding the implementation of telepractice in speech and language services using a mixed-methods approach. Wellcome Open Res. 2022, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. Health Care Seeking Practices and Barriers to Health Care Seeking for Suspected Pneumonia in Children Aged Less Than Five Years in Tribal and Non-Tribal Rural Areas of Pune District, India. Edinburgh Medical School Thesis And Dissertation Collection, 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1842/41127 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Tulimiero, M.; Garcia, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Cheney, A.M. Overcoming barriers to health care access in rural Latino communities: An innovative model in the eastern Coachella Valley. J. Rural Health 2021, 37, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, A.; Smith, A.C.; Mehrotra, A.; Page, M.; Caffery, L.J. A comparison study between metropolitan and rural hospital-based telehealth activity to inform adoption and expansion. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeland, A.G.; Bowes, A.; Flottorp, S. Effectiveness of telemedicine: A systematic review of reviews. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 736–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidholm, K.; Ekeland, A.G.; Jensen, L.K.; Rasmussen, J.; Pedersen, C.D.; Bowes, A.; Bech, M. A model for assessment of telemedicine applications: Mast. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2012, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.H.; Bhuiya, A.; Ghaffar, A. Engaging stakeholders in implementation research: Lessons from the Future Health Systems Research Programme experience. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Glasgow, R.E.; Chambers, D.A. What can implementation science do for you? Key success stories from the field. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapport, F.; Clay-Williams, R.; Churruca, K.; Shih, P.; Hogden, A.; Braithwaite, J. The struggle of translating science into action: Foundational concepts of implementation science. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. Determining Sample Size; How to Calculate Survey Sample Size. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Syst. 2017, 2. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3224205 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Jesudass, N.; Ramkumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Venkatesh, L. Development of a conceptual framework to understand the stakeholder’s perspectives on needs and readiness of rural tele-practice for childhood communication disorders. Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C. How we design feasibility studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, A.; Dewey, A. The sociogram: A useful tool in the analysis of focus groups. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, J.M.; Gultekin, L.; Brush, B.L. Using sociograms to enhance power and voice in focus groups. Public Health Nurs. 2015, 32, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Van Wynsberghe, R. Cultivating the under-mined: Cross-case analysis as knowledge mobilization. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research; Institut für Qualitative Forschung: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Volume 9, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–736. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Our general principles for teaching qualitative research. Psychologist 2013, 26, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Srivastava, S.; Lalchandani, A.; Mehta, J.L. Evolving role of telemedicine in health care delivery in India. Prim Health Care 2017, 7, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J.; Jacobs, M. Survey of ENT services in Africa: Need for a comprehensive intervention. Glob. Health Action 2009, 2, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Imam, M.H.; Jahan, I.; Das, M.C.; Muhit, M.; Akbar, D.; Badawi, N.; Khandaker, G. Situation analysis of rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities in Bangladesh: Identifying service gaps and scopes for improvement. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 5571–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.; Dally, K.; Duncan, J. Services for children with hearing loss in urban and rural Australia. Aust. J. Rural Health 2020, 28, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.; Vajaratkar, V.; Divan, G.; Hamdani, S.U.; Leadbitter, K.; Taylor, C.; Rahman, A. Parents’ perspectives on care of children with autistic spectrum disorder in South Asia–Views from Pakistan and India. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekola, B.; Kinfe, M.; Girma Bayouh, F.; Hanlon, C.; Hoekstra, R.A. The experiences of parents raising children with developmental disabilities in Ethiopia. Autism 2023, 27, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, M.B.; Nabbouh, F.; Shehata, S.; Ghahari, S. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare access for children with disabilities in low and middle income sub-Saharan African countries: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, A.; Bulkeley, K.; Veitch, C.; Bundy, A.; Gallego, G.; Lincoln, M.; Brentnall, J.; Griffiths, S. Addressing the barriers to accessing therapy services in rural and remote areas. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.; Grills, N.; Mathias, K. Barriers in health care access faced by children with intellectual disabilities living in rural Uttar Pradesh. J. Soc. Incl. 2015, 6, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkabile, S.; Swartz, L. ‘I waited for it until forever’: Community barriers to accessing intellectual disability services for children and their families in Cape Town, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkabile, S.; Swartz, L. Putting cultural difference in its place: Barriers to access to health services for parents of children with intellectual disability in an urban African setting. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earde, P.T.; Praipruk, A.; Rodpradit, P.; Seanjumla, P. Facilitators and barriers to performing activities and participation in children with cerebral palsy: Caregivers’ perspective. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2018, 30, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, C.S.; Singh, S.; Ranjan, A.; Sundararaman, T. Social and systemic determinants of utilisation of public healthcare services in Uttar Pradesh. Econ. Polit Wkly 2018, 53, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Gulati, S.; Berman, B.D.; Hadders-Algra, M.; Williams, A.N.; Smythe, T.; Boo, N.Y. Global leadership is needed to optimize early childhood development for children with disabilities. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Paige, S.R.; Slone, H.; Gutierrez, A.; Lutzky, C.; Hedriana, H.; Bunnell, B.E. Exploring telemental health practice before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Telemed. Telecare 2024, 30, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, J.L.; Rowlandson, J.; Beers, A.; Small, S. Telehealth-enabled auditory brainstem response testing for infants living in rural communities: The British Columbia Early Hearing Program experience. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, V.; Nagarajan, R.; Shankarnarayan, V.C.; Kumaravelu, S.; Hall, J.W. Implementation and evaluation of a rural community-based pediatric hearing screening program integrating in-person and tele-diagnostic auditory brainstem response (ABR). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarnia, J. The Effect of Telehealth on Autism Diagnosis and Evaluation Seen Through Patient Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA, 2023. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/46120 (accessed on 10 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.L.; Ward, E.C.; Gray, A.; Baker, L.; Cowie, B.; Winter, N.; Turvey, J. Implementation of speech pathology telepractice services for clinical swallowing assessment: An evaluation of service outcomes, costs and consumer satisfaction. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luryi, A.L.; Tower, J.I.; Preston, J.; Burkland, A.; Trueheart, C.E.; Hildrew, D.M. Cochlear implant mapping through telemedicine—A feasibility study. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e330–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarżyński, P.H.; Świerniak, W.; Bruski, Ł.; Ludwikowski, M.; Skarżyński, H. Comprehensive approach to the national network of teleaudiology in world hearing center in Kajetany, Poland. Finn. J. Ehealth Ewelfare 2018, 10, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarżyński, P.H.; Świerniak, W.; Ludwikowski, M.; Bruski, Ł. Telefitting between Kajetany and Odessa, Ukraine for cochlear implants. J. Int. Soc. Telemed. Ehealth 2019, 7, e17-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, D.M.; Bernstein, C.M.; Calandrillo, D.; Muscato, N.; Introcaso, K.; Bosworth, C.; Olson, A.; Vovos, R.; Stillitano, G.; Sydlowski, S. Teledelivery of aural rehabilitation to improve cochlear implant outcomes. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claridge, R.; Kroll, N. Aural rehabilitation via telepractice during COVID-19: A global perspective on evolving early intervention practices. Int. J. Telerehabil. 2021, 13, e6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Marzaleh, M.A.; Zakerabbasali, S.; Ahmadi, A.; Sarpourian, F. Comparing the clinical effectiveness of telerehabilitation with traditional speech and language rehabilitation in children with hearing disabilities: A systematic review. Telemed. E-Health 2024, 30, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, T.; Jijo, P.M.; Lavanya, H.S.; Malthesh, H.R. Teletherapy for children with communication disorders: A survey on parental opinion. Int. J. Speech Audiol. 2023, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tananuchittikul, P.; Yimtae, K.; Chayaopas, N.; Thanawirattananit, P.; Kasemsiri, P.; Piromchai, P. App-Based Hearing Screenings in Preschool Children With Different Types of Headphones: Diagnostic Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e44703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zou, B.; Gao, L.; Weng, M.; Lando, M.; Smith, A.E.; Yao, H. A novel tablet-based approach for hearing screening of the pediatric population, 516-patient study. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, M.E.; Brennan-Jones, C.G.; Kuthubutheen, J. Remote paediatric ear examination comparing video-otoscopy and still otoscopy clinician rated outcomes. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 177, 111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, E.M.; Jajko, K.; Reid, A.; Locatelli-Smith, A.; McMahen, C.S.; Tao, K.F.; Brennan-Jones, C.G. Clinician-rated quality of video otoscopy recordings and still images for the asynchronous assessment of middle-ear disease. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, L.; Morris, M.; Serry, T.; Erickson, S. Mobile apps for treatment of speech disorders in children: An evidence-based analysis of quality and efficacy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; French, A.; Lake, A.; Tchuisseu, Y.P.; Repka, S.; Vasudeva, K.; Dong, C.; Whitaker, R.; Bettger, J.P. Describing perspectives of telehealth and the impact on equity in access to health care from community and provider perspectives: A multimethod analysis. Telemed. E-Health 2024, 30, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mui, B.; Lawless, M.; Timmer, B.H.; Gopinath, B.; Tang, D.; Venning, A.; May, D.; Muzaffar, J.; Bidargaddi, N.; Shekhawat, G.S. Australian hearing healthcare stakeholders’ experiences of and attitudes towards teleaudiology uptake: A qualitative study. Speech Lang. Hear. 2025, 28, 2372171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikhani, Y.; Bastani, P.; Rafiee, M.; Kavosi, Z.; Ravangard, R. Key barriers to the provision and utilization of mental health services in low-and middle-income countries: A scope study. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harniess, P.A.; Gibbs, D.; Bezemer, J.; Purna Basu, A. Parental engagement in early intervention for infants with cerebral palsy—A realist synthesis. Child: Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsbary, J.; Able, H.; Schertz, H.H.; Odom, S.L. Parents’ Voices Regarding Using Interventions for Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Early Interv. 2020, 43, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikelboom, R.H.; Bennett, R.J.; Manchaiah, V.; Parmar, B.; Beukes, E.; Rajasingam, S.L.; Swanepoel, D.W. International survey of audiologists during the COVID-19 pandemic: Use of and attitudes to telehealth. Int. J. Audiol. 2022, 61, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, P.; Del Monte, L.; Sotgiu, A.; De Giacomo, C.; Vignoli, A. Parents’ satisfaction of tele-rehabilitation for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suso-Martí, L.; La Touche, R.; Herranz-Gómez, A.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in physical therapist practice: An umbrella and mapping review with meta–meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.C.; Davidson, L.; Tancredi, D.J.; Burns, R.D.; Garrison, S.L.; Marcin, J.P. Parent, physician, and therapist experience of in-person, hybrid, and all-virtual models of physiatry care for children with special health care needs. Acad. Pediatr. 2024, 24, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.; Hussaindeen, J.R.; Jacob, N.; Sethuraman, S.; Swaminathan, M. Parental perception of facilitators and barriers to activity and participation in an integrated tele-rehabilitation model for children with cerebral visual impairment in South India–A virtual focus group discussion study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Themes |

|---|---|

| Category 1: Availability | Parents of CwDs—demand or need |

| Category 2: Barriers and challenges in seeking health care | |

| Category 3: Satisfaction with quality of health care | |

| Category 4: Suggestions to improve quality of health care | |

| Category 5: Perceptions on use of technology or mobile phones | Parents of CwDs—acceptability and integration of tele-practice services |

| Category 6: Rehabilitation—acceptance of new services | |

| Category 7: Screening—acceptance of new services |

| FGDs:7 (n = 53 Participants) and SSIs: 8 (n = 8 Participants) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | No. of FGDs/SSIs | No. of Participants (Distribution in Each Group) |

| Mothers of CwDs | 4 FGDs | 33 participants (14, 6, 7, 6 in each group) |

| Fathers of CwDs | 3 FGDs | 20 (8,6,6 in each group) |

| Fathers of CwDs | 8 SSIs | 8 participants (one to one interview) |

| Parent of CwnkDs | 1722 1242—mothers and 480—fathers (1015 from Ariyalur district and 707 from Perambalur district) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jesudass, N.; Ramkumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Venkatesh, L. Parents’ Perceptions Regarding Needs and Readiness for Tele-Practice Implementation Within a Public Health System for the Identification and Rehabilitation of Children with Hearing and Speech–Language Disorders in South India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060943

Jesudass N, Ramkumar V, Kumar S, Venkatesh L. Parents’ Perceptions Regarding Needs and Readiness for Tele-Practice Implementation Within a Public Health System for the Identification and Rehabilitation of Children with Hearing and Speech–Language Disorders in South India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060943

Chicago/Turabian StyleJesudass, Neethi, Vidya Ramkumar, Shuba Kumar, and Lakshmi Venkatesh. 2025. "Parents’ Perceptions Regarding Needs and Readiness for Tele-Practice Implementation Within a Public Health System for the Identification and Rehabilitation of Children with Hearing and Speech–Language Disorders in South India" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060943

APA StyleJesudass, N., Ramkumar, V., Kumar, S., & Venkatesh, L. (2025). Parents’ Perceptions Regarding Needs and Readiness for Tele-Practice Implementation Within a Public Health System for the Identification and Rehabilitation of Children with Hearing and Speech–Language Disorders in South India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060943