Occupational Health Effects of Chlorine Spraying in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alternative Disinfectants and Application Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

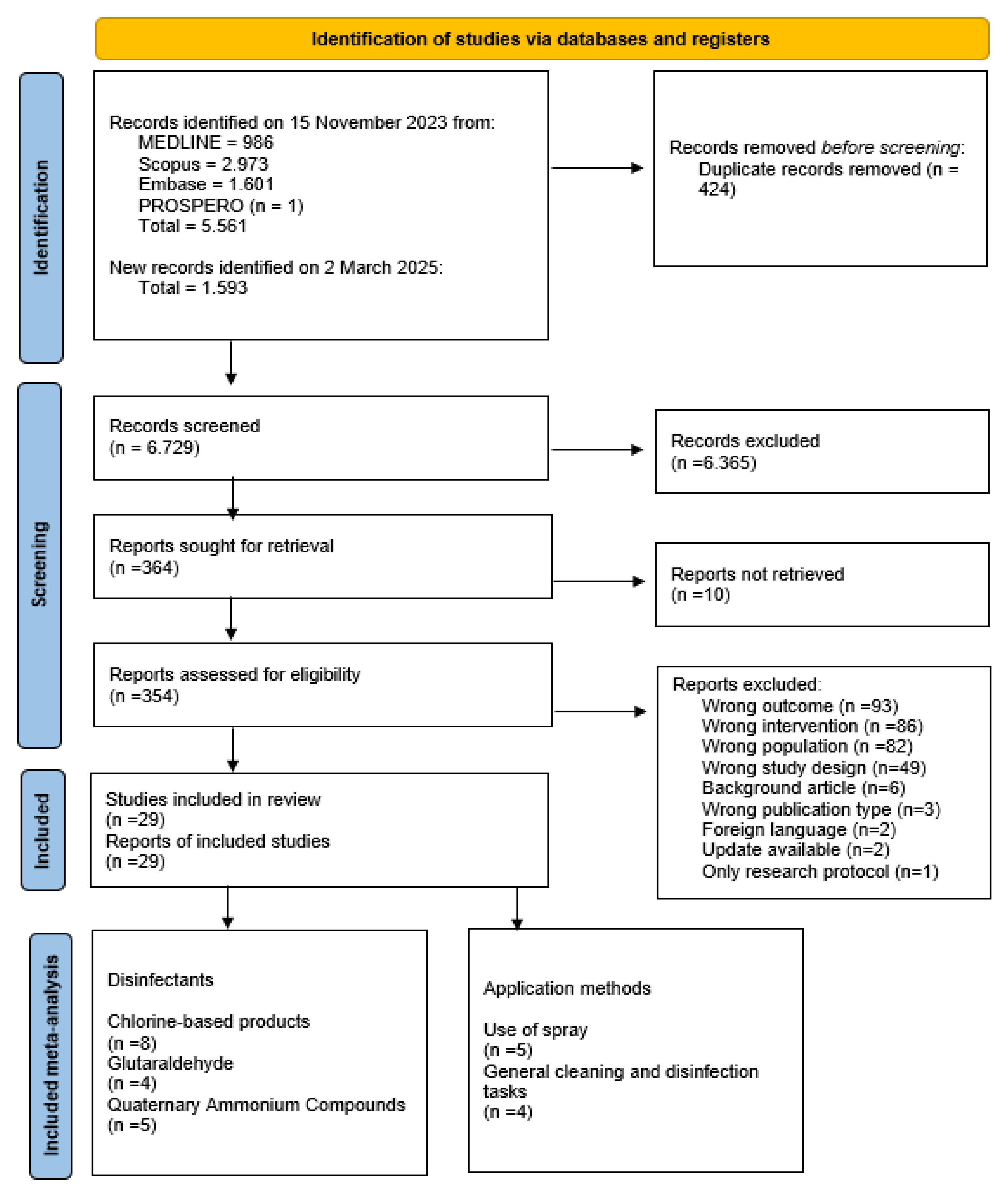

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.2. Risk of Bias and Quality of Evidence

2.3. Summary

2.4. Meta-Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chlorine-Based Products

3.2. Glutaraldehyde

3.3. Peracetic Acid, Acetic Acid, and Hydrogen Peroxide

3.4. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds

3.5. Other Disinfectants

3.6. Relative Odds Ratios for Disinfectants

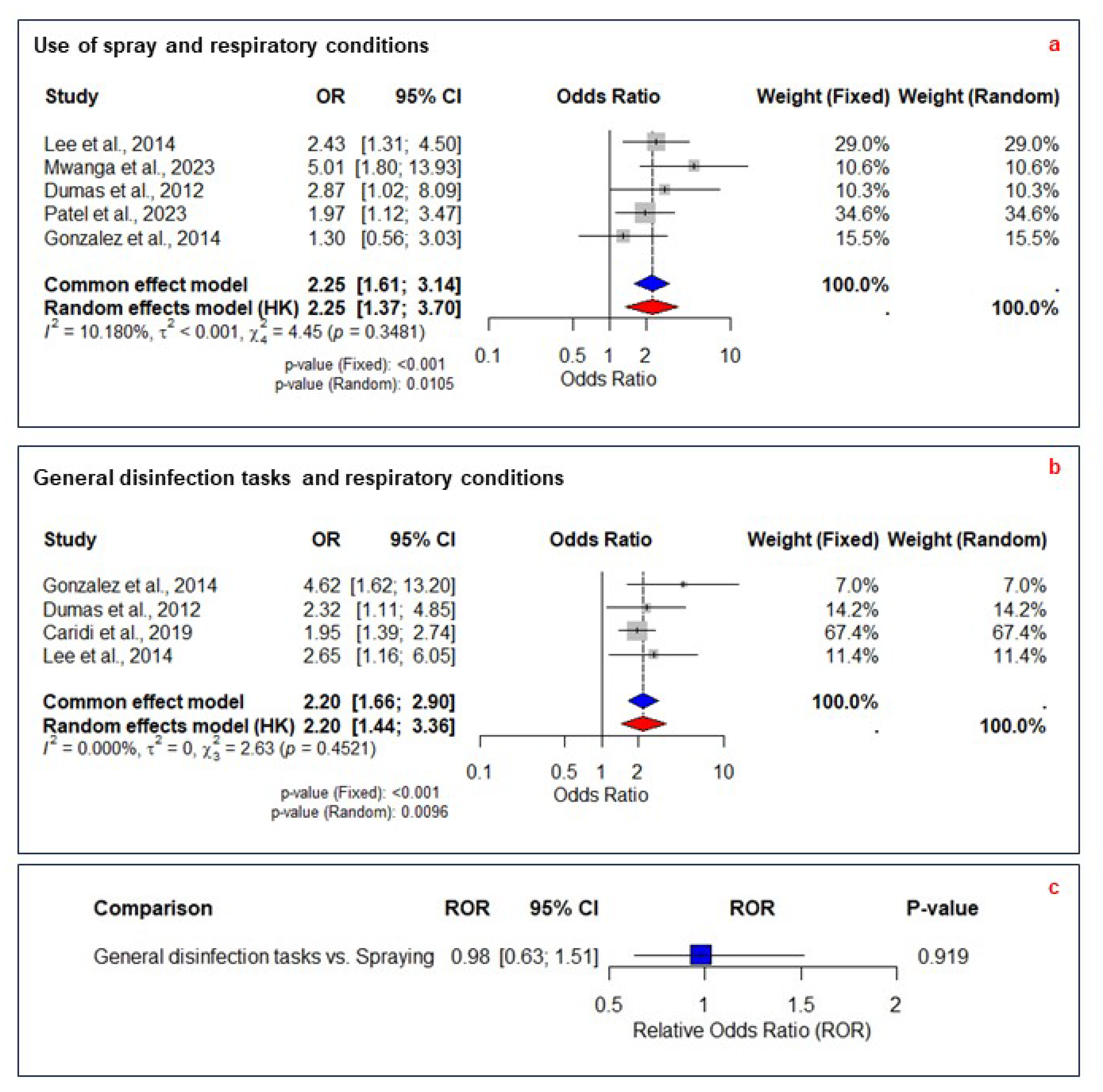

3.7. Application Methods

3.8. Relative Odds Ratios for Application Methods

3.9. Mitigation Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Disinfectants

4.2. Application Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Acetic Acid |

| ACH | Air Changes per Hour |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRS | Chemical-Related Symptoms |

| EC | Exposure Cluster |

| GDTs | General Disinfection Tasks |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| GU | Glutaraldehyde |

| HCWs | Healthcare Workers |

| HLDs | High-Level Disinfectants |

| HP | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| I2 | I-squared (statistical measure of heterogeneity) |

| JTEM | Job–Task–Exposure Matrix |

| MM | Mitigation Measure |

| OEL | Occupational Exposure Limit |

| ON | Ocular–Nasal Condition |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAA | Peracetic Acid |

| PECO | Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome |

| PEF | Peak Expiratory Flow |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QACs | Quaternary Ammonium Compounds |

| RC | Respiratory Condition |

| ROR | Relative Odds Ratio |

| SC | Skin Condition |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedure |

References

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). The ICTV Report on Virus Classification and Taxon Nomenclature. Genus: Orthoebolavirus. 2024. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/chapter/filoviridae/filoviridae/orthoebolavirus (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting. Public Health Service. 1998. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/65012 (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- World Health Organization. Ebola Guidance Package Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) Guidance Summary Background. 2014. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/131828 (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Carpenter, A.; Cox, A.T.; Marion, D.; Phillips, A.; Ewington, I. A case of a chlorine inhalation injury in an Ebola treatment unit. J. R. Army Med. Corps 2016, 162, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehtar, S.; Bulabula, A.N.H.; Nyandemoh, H.; Jambawai, S. Deliberate exposure of humans to chlorine-the aftermath of Ebola in West Africa. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2016, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control Guideline for Ebola and Marburg Disease. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WPE-CRS-HCR-2023.1 (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Wiemken, T.L.; Powell, W.; Carrico, R.M.; Mattingly, W.A.; Kelley, R.R.; Furmanek, S.P.; Johnson, D.; Ramirez, J.A. Disinfectant sprays versus wipes: Applications in behavioral health. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1698–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.; Kim, J.-H.; Strauch, A.; Wu, T.; Powell, J.; Roberge, R.; Shaffer, R.; Coca, A. Physiological Evaluation of Cooling Devices in Conjunction with Personal Protective Ensembles Recommended for Use in West Africa. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, T.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, S.; Lin, S.; Zheng, Z.; Fang, Z.; Chen, X. Field Investigation of the Heat Stress in Outdoor of Healthcare Workers Wearing Personal Protective Equipment in South China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1166056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Prisma-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Rabbit. Research Rabbit. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchrabbit.ai/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamliyan, T.A.; Kane, R.L.; Ansari, M.T.; Raman, G.; Berkman, N.D.; Grant, M.; Janes, G.; Maglione, M.; Moher, D.; Nasser, M.; et al. Development quality criteria to evaluate nontherapeutic studies of incidence, prevalence, or risk factors of chronic diseases: Pilot study of new checklists. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, S.I.; Verbeek, J.H.; Seidler, A.; Lindbohm, M.-L.; Ojajärvi, A.; Orsini, N.; Costa, G.; Neuvonen, K. Night-shift work and breast cancer—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2013, 39, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, K.R.; Kofahl, M.; Freiberg, A.; Schubert, M.; Groß, M.L.; Schmauder, S.; Hegewald, J.; Kämpf, D.; Stranzinger, J.; Nienhaus, A.; et al. Are Daycare Workers at a Higher Risk of Parvovirus B19 Infection? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Methodology Checklist. 2021. Available online: https://www.sign.ac.uk/using-our-guidelines/methodology/checklists/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program. CASP Checklist: Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies. 2006. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/systematic-reviews-meta-analysis-observational-studies/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Cochrane. How to include multiple groups from one study. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Chapter 23.3.4; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-23#section-23-3-4 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Cochrane Training. Identifying and Measuring Heterogeneity. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10#section-10-10-2 (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The GRADE Working Group. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach; GRADE Handbook; GRADE Working Group: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2013; Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackley, B.H.; Nett, R.J.; Cox-Ganser, J.M.; Harvey, R.R.; Virji, M.A. Eye and airway symptoms in hospital staff exposed to a product containing hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid, and acetic acid. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caridi, M.N.; Humann, M.J.; Liang, X.; Su, F.-C.; Stefaniak, A.B.; LeBouf, R.F.; Stanton, M.L.; Virji, M.A.; Henneberger, P.K. Occupation and task as risk factors for asthma-related outcomes among healthcare workers in New York City. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, M.L.; Hawley, B.; Edwards, N.; Cox-Ganser, J.M.; Cummings, K.J. Health problems and disinfectant product exposure among staff at a large multispecialty hospital. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.B.; Lee, F.Y.; Goh, M.M.; Lam, D.K.H.; Tan, A.B.H. Assessment of occupational exposure to airborne chlorine dioxide of healthcare workers using impregnated wipes during high-level disinfection of non-lumened flexible nasoendoscopes. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2018, 15, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, O.; Donnay, C.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Héry, M.; Choudat, D.; Kauffmann, F.; Le Moual, N. Occupational exposure to cleaning products and asthma in hospital workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, O.; Varraso, R.; Boggs, K.M.; Quinot, C.; Zock, J.-P.; Henneberger, P.K.; Speizer, F.E.; Le Moual, N.; Camargo, C.A. Association of Occupational Exposure to Disinfectants with Incidence of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among US Female Nurses. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1913563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, O.; Boggs, K.M.; Quinot, C.; Varraso, R.; Zock, J.; Henneberger, P.K.; Speizer, F.E.; Le Moual, N.; Camargo, C.A. Occupational exposure to disinfectants and asthma incidence in U.S. nurses: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, O.; Gaskins, A.J.; Boggs, K.M.; Henn, S.A.; Le Moual, N.; Varraso, R.; Chavarro, J.E.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Occupational use of high-level disinfectants and asthma incidence in early to mid-career female nurses: A prospective cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, O.; Wiley, A.S.; Quinot, C.; Varraso, R.; Zock, J.-P.; Henneberger, P.K.; Speizer, F.E.; Le Moual, N.; Camargo, C.A. Occupational exposure to disinfectants and asthma control in US nurses. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrin, W.J.; Cavalieri, S.A.; Wald, P.; Becker, C.E.; Jones, J.R.; Cone, J.E. Evidence of Neurologic Dysfunction Related to Long-term Ethylene Oxide Exposure. Arch. Neurol. 1987, 44, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, P.F.G.; Bright, P.; Campbell, M.; O’Hickey, S.P.; Sherwood Burge, P. Occupational asthma due to glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde in endoscopy and x ray departments. Thorax 1995, 50, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.N.; House, R.; Lipszyc, J.C.; Liss, G.M.; Holness, D.L.; Tarlo, S.M. Cleaning agent usage in healthcare professionals and relationship to lung and skin symptoms. J. Asthma 2022, 59, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, A.J.; Chavarro, J.E.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Missmer, S.A.; Laden, F.; Henn, S.A.; Lawson, C.C. Occupational use of high-level disinfectants and fecundity among nurses. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2017, 43, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Jégu, J.; Kopferschmitt, M.; Donnay, C.; Hedelin, G.; Matzinger, F.; Velten, M.; Guilloux, L.; Cantineau, A.; de Blay, F. Asthma among workers in healthcare settings: Role of disinfection with quaternary ammonium compounds. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 44, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, B.; Casey, M.; Virji, M.A.; Cummings, K.J.; Johnson, A.; Cox-Ganser, J. Respiratory symptoms in hospital cleaning staff exposed to a product containing hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid, and acetic acid. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2018, 62, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, L.; Anderson, K.; Kurth, L.; Liang, X.; Groth, C.P.; England, L.; Laney, A.S.; Virji, M.A. Characterization of Cleaning and Disinfection Product Use, Glove Use, and Skin Disorders by Healthcare Occupations in a Midwestern Healthcare Facility. Buildings 2022, 12, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, L.; Virji, M.A.; Storey, E.; Framberg, S.; Kallio, C.; Fink, J.; Laney, A.S. Current asthma and asthma-like symptoms among workers at a Veterans Administration Medical Center. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde-Castérot, H.; Villa, A.F.; Rosenberg, N.; Dupont, P.; Lee, H.M.; Garnier, R. Occupational rhinitis and asthma due to EDTA-containing detergents or disinfectants. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2012, 55, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Nam, B.; Harrison, R.; Hong, O. Acute symptoms associated with chemical exposures and safe work practices among hospital and campus cleaning workers: A pilot study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Hovcová, A.; Fenclová, Z.; Pelclová, D. Occupational skin diseases in Czech healthcare workers from 1997 to 2009. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 86, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, H.H.; Baatjies, R.; Jeebhay, M.F. Occupational risk factors and exposure-response relationships for airway disease among health workers exposed to cleaning agents in tertiary hospitals. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 80, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebzadeh, A. The effect of work practices on personal exposure to glutaraldehyde among health care workers. Ind. Health 2007, 45, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ndlela, N.H.; Naidoo, R.N. Job and exposure intensity among hospital cleaning staff adversely affects respiratory health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettis, E.; Colanardi, M.C.; Soccio, A.L.; Ferrannini, A.; Tursi, A. Occupational irritant and allergic contact dermatitis among healthcare workers. Contact Dermat. 2002, 46, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbäck, D. Skin and respiratory symptoms from exposure to alkaline glutaraldehyde in medical services. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1988, 14, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterspoor, S.; Farrell, J. An evaluation of buffered peracetic acid as an alternative to chlorine and hydrogen peroxide based disinfectants. Infect. Dis. Health 2019, 24, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; de Porras, D.G.R.; Mitchell, L.E.; Carson, A.; Whitehead, L.W.; Han, I.; Pompeii, L.; Conway, S.; Zock, J.-P.; Henneberger, P.K.D.; et al. Cleaning Tasks and Products and Asthma Among Healthcare Professionals. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 66, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.-C.; Friesen, M.C.; Humann, M.; Stefaniak, A.B.; Stanton, M.L.; Liang, X.; LeBouf, R.F.; Henneberger, P.K.; Virji, M.A. Clustering asthma symptoms and cleaning and disinfecting activities and evaluating their associations among healthcare workers. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archangelidi, O.; Sathiyajit, S.; Consonni, D.; Jarvis, D.; De Matteis, S. Cleaning products and respiratory health outcomes in occupational cleaners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starke, K.R.; Friedrich, S.; Schubert, M.; Kämpf, D.; Girbig, M.; Pretzsch, A.; Nienhaus, A.; Seidler, A. Are Healthcare Workers at an Increased Risk for Obstructive Respiratory Diseases Due to Cleaning and Disinfection Agents? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickmann, M.; Gravemann, U.; Handke, W.; Tolksdorf, F.; Reichenberg, S.; Müller, T.H.; Seltsam, A. Inactivation of Ebola virus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in platelet concentrates and plasma by ultraviolet C light and methylene blue plus visible light, respectively. Transfusion 2018, 58, 2202–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, F.E.; Kabra, K.B.; Tritsch, S.R.; Montgomery, J.M.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Mores, C.N.; Harcourt, B.H. Exploring inactivation of SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, Ebola, Lassa, and Nipah viruses on N95 and KN95 respirator material using photoactivated methylene blue to enable reuse. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, Year, Study Design | Risk of Bias | Study Objective | Type of Recruitment, Population | Sample Size, Sex, Age | Exposure (Category), Assessment | Outcome (Cluster) Assessment | Adjustment Confounding | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackley et al., 2023 [24] Cross-sectional | Low | To assess associations among exposures to PAA, AA, and HP and work-related eye and airway symptoms | Hospital staff performing cleaning duties and other staff in areas where cleaning occurred | 67, 76% female, median age 47 years | Personal or mobile samples for HP, PAA, and AA; additional area samples (PAA, AA, and HP, MM) | Eye, skin, upper and lower airway symptoms assessed via post-shift survey (RC, ON) | Age, gender, smoking status, use of other products | PAA, AA, and HP associated with ON and RC |

| Caridi et al., 2019 [25] Cross-sectional | High | To investigate the association of asthma and related outcomes with occupations and tasks | Members of the Service Employees International Union | 2030, 76% female, average age 48.6 years | Questionnaire on demographic characteristics, tasks performed, products used in healthcare occupations, and occurrence of asthma and related health outcomes (unspecified products) | Post-hire asthma, current asthma, exacerbation of asthma, BHR-related symptoms, asthma score, and wheeze (RC) | Gender, age, race, smoking status, allergies | Surface cleaning associated with RC |

| Casey et al., 2017 [26] Cross-sectional | High | To assess health effects of PAA, AA, and HP | Current staff of the hospital (volunteers) | 163, 50 males, 113 females, 49 air samples | Air samples PAA, AA, and HP (PAA, AA, and HP) | Work-related symptoms, questionnaire (RC, ON) | Demographic, smoking status | PAA, AA, and HP associated with ON |

| Chang et al., 2018 [27] Case report | High | To assess the exposure of HCWs to airborne chlorine dioxide | HCWs who performed nasoendoscope disinfection | 14 long-term personal air samples, 4 short-term personal air samples, 16 long-term area samples | ClO2 levels measured using ion-chromatograph after collection in midget impingers (chlorine, MM) | ClO2 concentrations were all below the OEL (RC) | N/A | Ventilation mitigates the risk |

| Dumas et al., 2012 [28] Cross-sectional | High | To determine the associations between asthma and occupational exposure to cleaning agents | HCWs and a reference population from the French cohort study (EGEA) | 543, N/A, 18–79 years | Self-report, expert assessment, and asthma-specific job-exposure matrix (chlorine, spray, GDTs) | Asthma (RC) | Age, smoking status, BMI | Use of spray associated with asthma |

| Dumas et al., 2019 [29] Cohort | High | To investigate the association between exposure to disinfectants and COPD incidence in a large cohort of US female nurses | Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) | 73,262 females, age at baseline was 54.7 years | Occupational exposure to disinfectants, evaluated by questionnaire and a job–task–exposure matrix (JTEM) | Incident physician-diagnosed COPD evaluated by questionnaire | age, smoking (pack-years), race, ethnicity, and body mass index | Regular use of chemical disinfectants among nurses may be a risk factor for developing COPD |

| Dumas et al., 2020 [30] Cohort | High | To investigate the association between occupational exposure to disinfectants and asthma incidence in cohort of U.S. female nurses | Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) | 61,539 females, mean age 55 years at baseline | Occupational exposure to disinfectants evaluated by questionnaire and JTEM (chlorine, PAA, AA, HP, GU, QACs) | Incident physician-diagnosed asthma reported during follow-up (RC) | Age, race, ethnicity, smoking status, BMI | Disinfectants not associated with asthma |

| Dumas et al., 2021 [31] Cohort | High | To investigate the association between use of HLDs and asthma incidence | Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) | 17,280 female, mean age 34 years | Self-reported use of HLDs via questionnaire; duration of use; type of HLDs used in the past month; frequency of PPE use (chlorine, PAA, AA, HP, GU, QACs) | Incident clinician-diagnosed asthma reported during follow-up (RC) | Age, race, ethnicity, smoking status, BMI | HLDs associated with asthma |

| Dumas et al., 2017 [32] Cross-sectional | High | To examine the association between occupational exposure to disinfectants and asthma control in U.S. nurses | Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) | 4102 females, mean age 58 years | Occupational exposure to disinfectants evaluated by JTEM and self-reported disinfection tasks (chlorine, PAA, AA, HP, GU, QACs) | Asthma control measured using the Asthma Control Test (RC) | Age, smoking status, BMI, race, ethnicity | Disinfectants associated with poor asthma control |

| Estrin et al., 1987 [33] Case–control | High | To detect neurologic effects of chronic low-dose exposure to ethylene oxide | Hospital workers exposed to ethylene oxide and non-exposed controls | 8, female, N/A | Hygienic measurements in the breathing zone, personal sampling (MM) | Psychometric test, nerve conduction studies, EEG spectral analysis, standardized neurologic examination (NC) | N/A | Ethylene oxide associated with neurologic dysfunction |

| Gannon et al., 1995 [34] Case series | High | To investigate cases of occupational asthma due to GU | Workers referred to a specialist occupational lung disease clinic | 8, 7 females, 1 male, 29–53 years | Personal and static short and longer-term air samples, specific bronchial provocation tests (GU) | Occupational asthma by PEF measurements and specific bronchial provocation tests (RC) | N/A | GU associated with asthma |

| Garrido et al., 2022 [35] Case–control | High | To identify work tasks and cleaning/disinfecting agents associated with respiratory symptoms and hand dermatitis among HCWs in a tertiary hospital | Staff of three hospitals | 230 exposed, 80% female, 77 control, 84% female, median age 44 years | Questionnaire on cleaning agent usage, respiratory symptoms, and skin symptoms; frequency of specific tasks and cleaning agents used (chlorine) | Self-reported respiratory symptoms and hand dermatitis (RC) | Age, sex | Disinfectants associated with RC and skin symptoms |

| Gaskins et al., 2017 [36] Cohort | High | To examine the relationship between occupational use of HLDs and fecundity among female nurses | Participants from the Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3) | 1739 females, mean age 33.8 | Self-reported use of HLDs, frequency and duration of use, and use of PPE (MM) (multiple HLDs defined) | Duration of pregnancy attempt reported every six months | Age, BMI, smoking status, marital status, race | HLDs associated with reduced fecundity |

| Gonzalez et al., 2014 [37] Cross-sectional | High | To analyze associations between asthma and occupational exposure to disinfectants | Stratified random sampling of various healthcare departments | 543, 59 males, 474 females, mean age 39.9 years | Occupational exposure assessment through a work questionnaire, workplace studies (chlorine, GU, QACs, spray) | Asthma, new-onset asthma, nasal symptoms at work, specific IgE assays (RC, ON) | Age, BMI, gender, smoking status, co-exposures | Disinfectant’s dilution and mixing associated with RC |

| Hawley et al., 2018 [38] Cross-sectional | Low | To assess respiratory symptoms in hospital cleaning staff exposed to PAA, AA, and HP | Hospital cleaning staff on all three shifts | 50, 57% female, median age 40 years | Full-shift samples for HP, PAA, and AA; personal and mobile-area sampling; observation of cleaning tasks (PAA, AA, and HP) | Acute upper and lower airway symptoms from post-shift survey; chronic respiratory symptoms from extended questionnaire | Age, gender, and smoking status | PAA, AA, and HP associated with eye symptoms and RC |

| Kobos et al., 2022 [39] Cross-sectional | High | To characterize the prevalence of cleaning and disinfection product use, glove use during cleaning and disinfection, and skin/allergy symptoms by occupation | Current employees | 559, 77% female, median age 49 years | Questionnaire on cleaning and disinfection product use, glove use, and skin/allergy symptoms (chlorine, PAA, AA, and HP, QACs, MM) | Prevalence of skin disorders and allergic reactions, glove use frequency (SC) | Age, sex, occupation, and product use frequency | Bleach, alcohol, and QACs associated with skin disorders |

| Kurth et al., 2017 [40] Cross-sectional | High | To estimate the prevalence of current asthma and asthma-like symptoms and their association with workplace exposures and tasks | Convenience sample | 562, 78% female, mean age 46.5 years | Questionnaire on respiratory health, work characteristics, tasks performed, products used, and exposures (GDTs) | Self-reported current asthma, asthma-like symptoms, and breathing problems (RC) | Age, sex, race, smoking status, allergy | Disinfection tasks associated with RC |

| Laborde-Castérot et al., 2012 [41] Case series | High | To report cases of work-related rhinitis and asthma associated with exposure to EDTA-containing detergents or disinfectants | Patients with work-related rhinitis referred for NPT with EDTA | 28, 21 females | History of exposure to aerosols of EDTA-containing products, NPT with tetrasodium EDTA (1–4%) | Positive NPT, presence of rhinitis symptoms, asthma-like symptoms, pulmonary function tests | N/A | EDTA associated with RC |

| Lee et al., 2014 [42] Cross-sectional | High | To investigate acute symptoms associated with chemical exposures among HCW’s work practices | Convenience sample of HCWs employed | 183, 81 males, 102 females mean age 48 years | Self-reported data on chemical exposure, tasks performed, and use of PPE (spray, GDTs) | CRS (respiratory, eye, skin, neurological, gastrointestinal), interviews, or questionnaires (RC) | Age, sex, and job title | Use of spray and disinfectants associated with CRS |

| Mac Hovcová et al., 2013 [43] Cohort | High | To analyze the causes and trends in allergic and irritant-induced skin diseases in the healthcare sector | Data extracted from the National Registry of Occupational Diseases in the Czech Republic from 1997 to 2009 | 545, 95% female, mean age 38 years | Analysis of reported cases of occupational skin diseases, including patch testing and workplace hygiene evaluation | Prevalence and incidence of occupational skin diseases, trends over time, common causative agents | N/A | Disinfectants first cause of allergic skin diseases |

| Mehtar et al., 2016 [5] Cross-sectional | High | To determine the adverse effects of chlorine spray exposure on humans | Volunteers, including HCWs, Ebola survivors, and quarantined contacts | 1550, 576 males, 974 females, 19–50 years | Self-reported chlorine spray exposure, frequency, and clinical condition post-exposure (chlorine, spray) | Prevalence of eye, respiratory, and skin conditions following chlorine exposure (RC, ON, SC) | Ebola disease effects on eyes | Spray of chlorine associated with eye, skin, and RC |

| Mwanga et al., 2023 [44] Cross-sectional | Low | To investigate occupational risk factors and exposure–response relationships for airway disease among HCWs exposed to cleaning agents | Stratified random sampling | 699, 77% female, median age 42 years | Self-reported exposure to cleaning agents and related tasks, fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, blood samples for atopy determination (chlorine, GU, QACs, spray) | ASS, WRONS, WRAS, FeNO levels (ON, RC) | Atopy, gender, smoking, age | Disinfectants and use of spray associated with RC |

| Nayebzadeh, 2007 [45] Mix method | High | To evaluate the impact of work practices and general ventilation systems on HCWs’ peak exposure to GU | HCWs from five hospitals in Quebec, Canada | 42 personal samples, 53 HCWs interviewed | Breathing zone personal air samples, classified work practices, presence of local or general ventilation system (GU, MM) | Concentration of GU, exposure levels, prevalence of symptoms like headache and itchy eyes among HCWs | N/A | Work practices affect GU exposure |

| Ndlela & Naidoo, 2023 [46] Cross-sectional | Low | To investigate the relationship between exposure to cleaning and disinfecting agents and respiratory outcomes | Eligible cleaners from three public hospitals | 174, 81% female, mean age 43.2 years | Self-reported frequency and duration of cleaning tasks and agent exposure, skin prick testing, spirometry (chlorine, QACs) | Respiratory symptoms, chest illnesses (asthma, tuberculosis, hay fever, chronic bronchitis), lung function measures (RC) | Sex, age, smoking history, any allergy, smoke | Disinfectant associated with RC |

| Nettis et al., 2002 [47] Cohort | High | To determine the prevalence and causes of occupational irritant and allergic contact dermatitis | HCWs referred to the Section of Allergy and Clinical Immunology at the University of Bari from 1994 to 1998 | 360, 280 females, 80 males; mean age 37.8 years | Patch testing with standard series and ‘health’ screening series, additional patch test with rubber allergens when necessary | Positive patch test reactions, diagnoses of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis | N/A | Disinfectants associated with allergic contact dermatitis |

| Norbäck, 1988 [48] Cross-sectional | Low | To study the prevalence of certain symptoms among HCWs with and without exposure to GU during cold sterilization | HCWs handling GU and a reference group of unexposed workers | 107, 98 females | Hygienic measurements in the breathing zone (GU, MM) | Self-reported symptoms from a questionnaire, including eye, skin, and airway symptoms, headache, nausea, and fatigue (ON, RC) | Demographic data | Ventilation mitigates GU exposure; GU associated with RC |

| Otterspoor & Farrell, 2019 [49] Case report | High | To evaluate buffered PAA as an alternative to chlorine and HP | NA | 20, N/A, N/A | Assessment of adverse staff reactions, safe-work related incident reporting (PAA, AA, and HP) | Acceptance, cost analysis, efficacy (RC) | N/A | PAA, AA, and HP higher acceptance than chlorine |

| Patel et al., 2023 [50] Cross-sectional | Low | To examine associations of cleaning tasks and products with WRAS in HCWs in Texas in 2016, comparing them to prior results from 2003 | Representative sample of Texas HCWs from state licensing boards | 2421, 83% female, average age 48.8 years; | Self-reported data on cleaning tasks, products used, and occupational exposures (chlorine, GU, QACs, spray) | Self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma, new onset asthma, work-exacerbated asthma, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness | Age, gender, race, atopy, obesity, smoking status, and years on the job | Use of spray, bleach, QACs associated with WRAS |

| Su et al., 2019 [51] Cross-sectional | High | To identify and group HCWs with similar patterns of asthma symptoms and explore their associations with patterns of cleaning and disinfecting activities (CDAs) | HCWs from nine selected occupations | 2029, 1542 females, 487 males, N/A | Self-reported information on asthma symptoms/care, CDAs, demographics, smoking status, allergic status (chlorine, QACs) | Asthma symptom clusters and their associations with exposure clusters (ECs) through multinomial logistic regression (RC) | Age, gender, education, smoking status, and allergic status | Chlorine associated with RC |

| Intervention or Comparison | OR/ROR. (95% CI) | Quality of Study (Risk of Bias) High ↓ | Inconsistency I2 > 50% ↓ | Indirectness of Evidence ↓ | Imprecision Cl Crossing 1 ↓ | Publication Bias, Yes or Unclear ↓ | Overall Certainty of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorine-Based Products | OR: 1.71 (1.41–2.08) | Yes ↓ 1 | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | Moderate |

| Glutaraldehyde | OR: 1.44 (1.14–1.81) | Yes ↓ 1 | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | Moderate |

| QACs | OR: 1.39 (0.69–2.78) | Yes ↓ 2 | Yes ↓ 4 | None (-) | Yes ↓ 5 | None (-) | Very Low |

| Glutaraldehyde vs. Chlorine | ROR: 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | Yes ↓ 3 | Not applicable | None (-) | Yes ↓ 5 | Not applicable | Low |

| QACs vs. Chlorine | ROR: 0.81 (0.39–1.68) | Yes ↓ 3 | Not applicable | None (-) | Yes ↓ 5 | Not applicable | Low |

| Use of spray | OR: 2.25 (1.61–3.14) | Yes ↓ 1 | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | Moderate |

| GDTs | OR: 2.20 (1.66–2.90) | Yes ↓ 1 | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | None (-) | Moderate |

| GDTs vs. Spraying | ROR: 0.98 (0.63–1.51) | Yes ↓ 3 | Not applicable | None (-) | Yes ↓ 5 | Not applicable | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fontana, L.; Stabile, L.; Caracci, E.; Chaillon, A.; Kothari, K.U.; Buonanno, G. Occupational Health Effects of Chlorine Spraying in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alternative Disinfectants and Application Methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060942

Fontana L, Stabile L, Caracci E, Chaillon A, Kothari KU, Buonanno G. Occupational Health Effects of Chlorine Spraying in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alternative Disinfectants and Application Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060942

Chicago/Turabian StyleFontana, Luca, Luca Stabile, Elisa Caracci, Antoine Chaillon, Kavita U. Kothari, and Giorgio Buonanno. 2025. "Occupational Health Effects of Chlorine Spraying in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alternative Disinfectants and Application Methods" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060942

APA StyleFontana, L., Stabile, L., Caracci, E., Chaillon, A., Kothari, K. U., & Buonanno, G. (2025). Occupational Health Effects of Chlorine Spraying in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alternative Disinfectants and Application Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060942