Dietary Practices and Anthropometric Status of the Rural University Students in Limpopo Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population, Sample Size, and Sampling Procedure

2.3. Variables Measured

2.4. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

2.5. Anthropometrics Measurements

2.6. Dietary Practices

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Students

3.2. Dietary Practices of Students

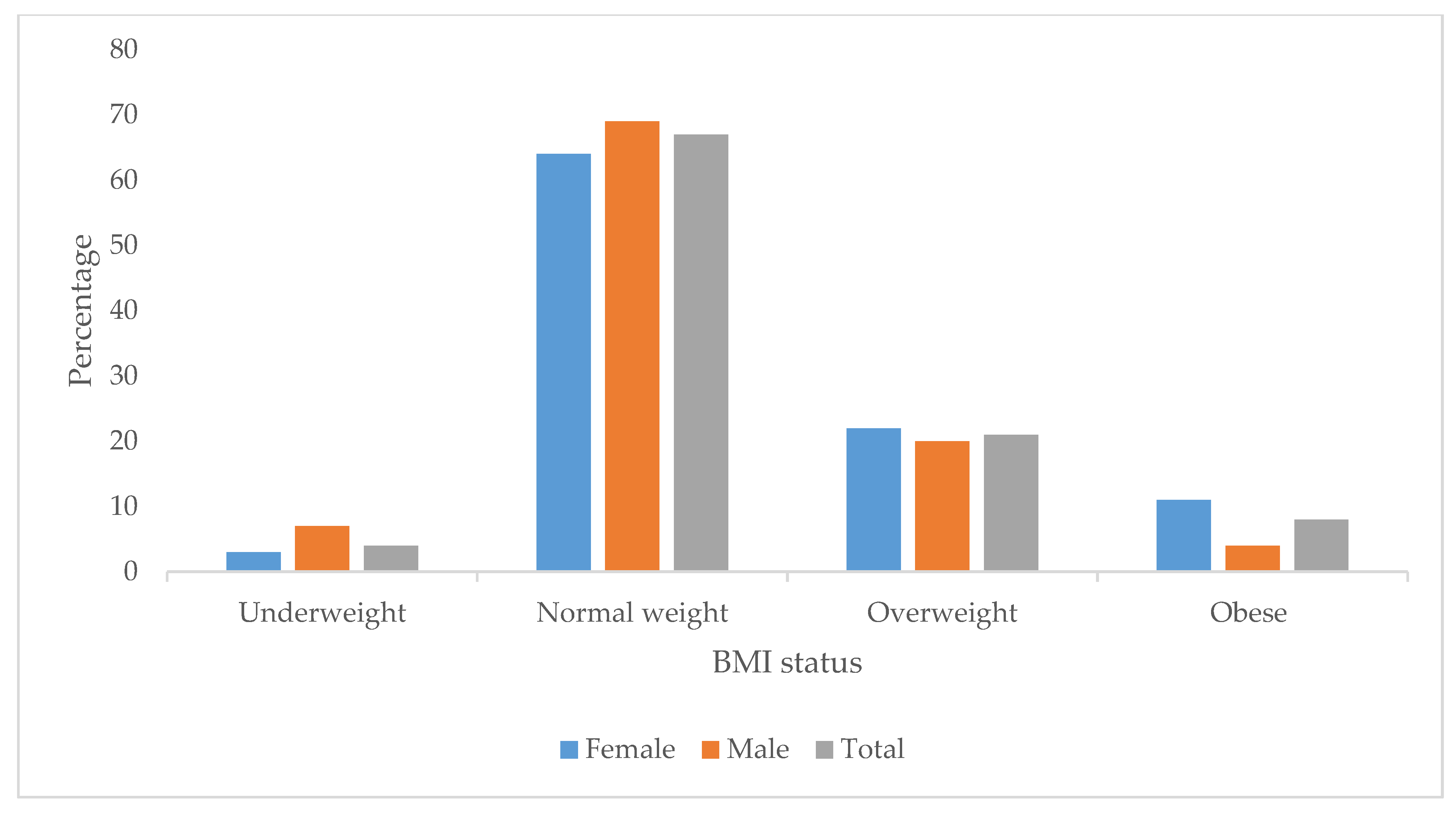

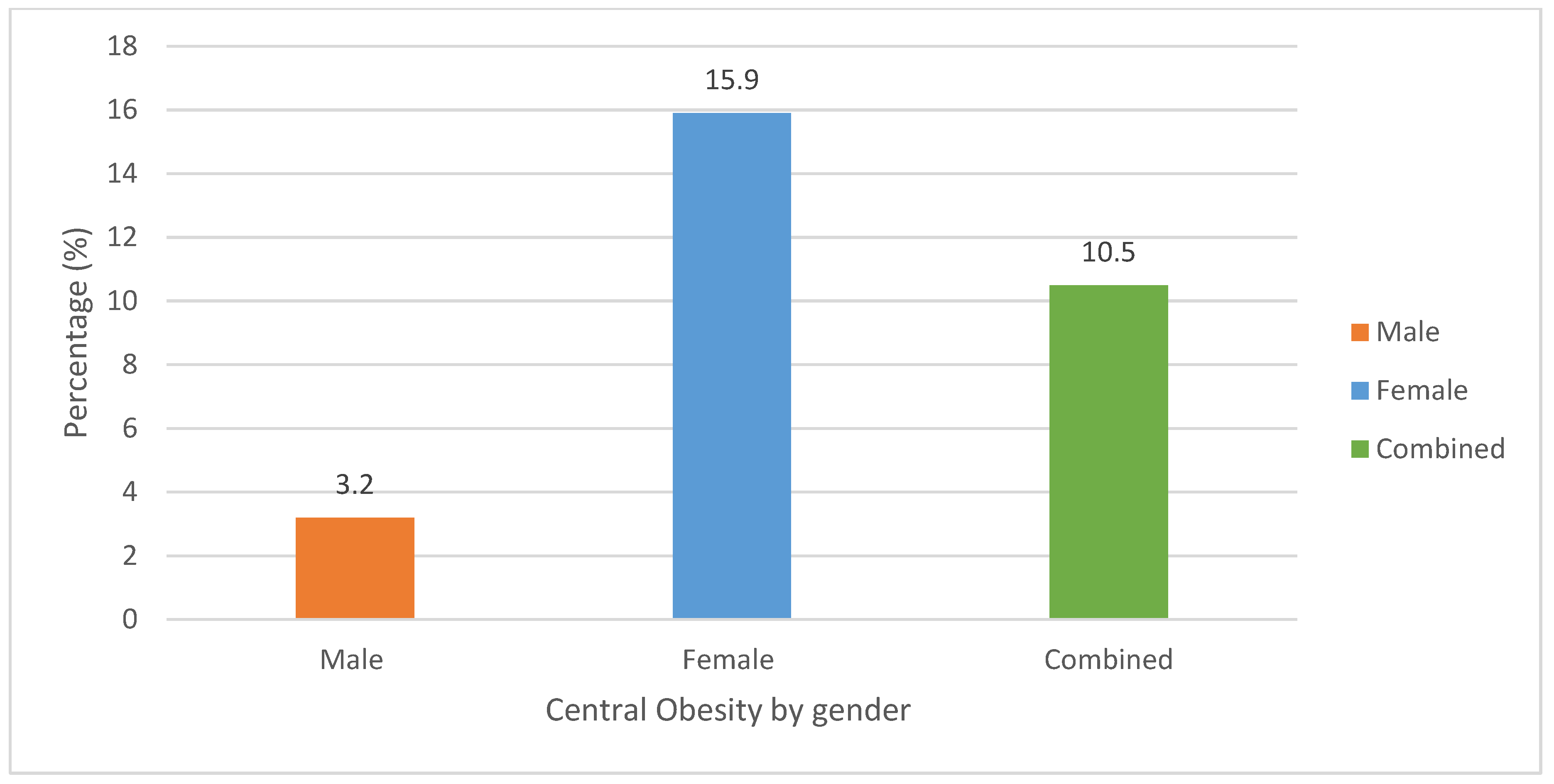

3.3. Anthropometric Status of Students

3.4. The Relationship Between Dietary Practices and Body Mass Index (BMI) Status of Students

3.5. The Association Between Dietary Practices and Waist-to-Hip Ratio Status of Students

3.6. The Association Between University Students’ Anthropometric Status and Dietary Practices

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCDs | non-communicable diseases |

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Pizzi, M.A.; Vroman, K. Childhood obesity: Effects on children’s participation, mental health, and psychosocial development. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2013, 27, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, E.; Fismen, A.S.; Helleve, A.; Hongoro, C.; Sewpaul, R.; Reddy, P.; Alaba, O.; Harbron, J. Trends in prevalence of overweight and obesity among South African and European adolescents: A comparative outlook. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cois, A.; Day, C. Obesity trends and risk factors in the South African adult population. BMC Obes. 2015, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shisana, O.; Labadarios, D.; Rehle, T.; Simbayi, L.; Zuma, K.; Dhansay, A.; Reddy, P.; Parker, W.; Hoosain, E.; Naidoo, P.; et al. The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; Department of Health Republic of South Africa; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.M.; Danaei, G.; Farzadfar, F.; Stevens, G.A.; Woodward, M.; Wormser, D.; Kaptoge, S.; Whitlock, G.; Qiao, Q.; Lewington, S.; et al. The age-specific quantitative effects of metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: A pooled analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. Continuum of Care for Noncommunicable Disease Management During the Migration Cycle; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 28 February 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240044401 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Progress Monitor 2022; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/353048/9789240047761-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. 2010. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44399/9789?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Gouda, H.N.; Charlson, F.; Sorsdahl, K.; Ahmadzada, S.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.; Leung, J.; Santamauro, D.; Lund, C.; Aminde, L.N.; et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1375–e1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.M.; Alonazi, W.B.; Vinluan, J.M.; Almigbal, T.H.; Batais, M.A.; Alodhayani, A.A.; Alsadhan, N.; Tumala, R.B.; Moussa, M.; Aboshaiqah, A.E.; et al. Health promoting lifestyle of university students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional assessment. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamil, H.A.; Alhakbany, M.A.; Alfadda, N.A.; Almusallam, S.M.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. A profile of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, sleep, and dietary habits of Saudi college female students. J. Fam. Community Med. 2019, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan, L.G.; Mehrzad, R. Environmental factors related to the obesity epidemic. In Obesity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ejigu, B.A.; Tiruneh, F.N. The link between overweight/obesity and noncommunicable diseases in Ethiopia: Evidences from nationwide WHO STEPS survey 2015. Int. J. Hypertens. 2023, 2023, 2199853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vhembe District Municipality. (n.d.). Development and planning: Retail and commercial growth in Vhembe. Vhembe District Municipality 2021/22. Available online: https://www.vhembe.gov.za/download/106/april-2021/1892/vhembe-district-municipality-2021-22-draft-idp-review.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Mallory, M.; Smith, J. Impact of retail development on consumer behavior in suburban areas. J. Retail Consum. Stud. 2021, 34, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts, M.; Nienaber, H. The influence of socioeconomic factors on dietary habits of students in South Africa. J. Nutr. Health 2019, 22, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, R.; Swart, R. Dietary practices and anthropometric status of rural South African youth. S. Afr. J. Public Health 2015, 41, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The UNICEF Conceptual Framework on Malnutrition; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza-Ros, F.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; Marfell-Jones, M. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment; International Society for Advancement of Kinanthropometry: Glasgow, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.R.; Hunt, M.J.; Brown, T.P.; Norgan, N.G. Waist-hip circumference ratio and its relation to age and overweight in British men. Human Nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 1986, 40, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Brannsether, B.; Roelants, M.; Bjerknes, R.; Júlíusson, P. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio in Norwegian children 4–18 years of age: Reference values and cut-off levels. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. 2003; WHO Technical Report Series No. 916. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924120916X (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Onurlubaş, E.; Yılmaz, N. Fast food consumption habits of university students. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaibi, H.H.; Basuny, A.M. Fast food consumption associated with obesity/overweight risk among university female student in Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Nutr. 2015, 14, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motadi, S.A.; Veldsman, T.; Mohlala, M.; Mabapa, N.S. Overweight and obesity among adults aged 18–45 years residing in and around Giyani town in Mopani district of Limpopo province, South Africa. J. Nutr. Health Sci. 2018, 5, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Mvo, Z. Perceptions of overweight African women about acceptable body size of women and children. Curationis 1999, 22, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaun, M.M.; Nizum, M.W.; Munny, S.; Fayeza, F.; Mali, S.K.; Abid, M.T.; Hasan, A.R. Eating habits and lifestyle changes among higher studies students post-lockdown in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabotata, S.; Malatji, T.L. Factors influencing fast food consumption: A case study of University of Venda Students, Limpopo, South Africa. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 26, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, S.S.; Thapa, K.; Bhatt, L.D.; Dhami, S.S.; Wagle, S. Determinants of junk food consumption among adolescents in Pokhara Valley, Nepal. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 644650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. Fast food pattern and cardiometabolic disorders: A review of current studies. Health Promot. Perspect. 2015, 5, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, N.J.; Steyn, N.P. Sugar and health: A food-based dietary guideline for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S100–S104. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, S.; Noriega, B.R.; Shin, J.Y. College students eating habits and knowledge of nutritional requirements. J. Nutr. Hum. Health 2018, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.A.; Adams, M.; Sabaté, J. The consumption of ultra-processed foods and non-communicable diseases in Latin America. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 622714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrottesley, S.V.; Pedro, T.M.; Fall, C.H.; Norris, S.A. A review of adolescent nutrition in South Africa: Transforming adolescent lives through nutrition initiative. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 33, 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, C.E. “Eat plenty of vegetables and fruit every day”: A food-based dietary guideline for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S46–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Bede, F.; Cumber, S.N.; Nkfusai, C.N.; Venyuy, M.A.; Ijang, Y.P.; Wepngong, E.N.; Kien, A.T. Dietary habits and nutritional status of medical school students: The case of three state universities in Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.C.; Ahmad, S.R.; Quee, D.K. Dietary habits and lifestyle practices among university students in Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 2018, 25, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, M.C.; Briones, U.M.; de Jesús, E.A.; Toledo, L.Á. Eating habits associated with nutrition-related knowledge among university students enrolled in academic programs related to nutrition and culinary arts in Puerto Rico. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, K.R. Insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables among individuals 15 years and older in 28 low-and middle-income countries: What can be done? J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1105–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachat, C.; Nago EVerstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, S.A.; Day, N.E. The diet and its relationship to health. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nago, E.S.; Lachat, C.K.; Dossa, R.A.; Kolsteren, P.W. Association of out-of-home eating with anthropometric changes: A systematic review of prospective studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.A.; Vinyard, B.T. Fast food consumption of US adults: Impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micha, R.; Wallace, S.K.; Mozaffarian, D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2010, 121, 2271–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, L.A.; He, J.; Ogden, L.G.; Loria, C.; Vupputuri, S.; Myers, L.; Whelton, P.K. Legume consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 2573–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Yu, E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Understanding nutritional epidemiology and its role in policy. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age category: | ||

| 18–24 | 322 | 88.7 |

| 25–30 | 41 | 10.7 |

| Gender: | ||

| Males | 155 | 42.7 |

| Females | 208 | 57.3 |

| Ethnic group: | ||

| Northern and Southern Sotho | 72 | 19.8 |

| Venda | 154 | 42.4 |

| Tsonga | 78 | 21.5 |

| Swati | 40 | 11.0 |

| Other ethnic groups | 19 | 5.2 |

| Academic level: | ||

| First year | 83 | 22.9 |

| Second year | 116 | 32.0 |

| Third year | 112 | 30.9 |

| Honours | 36 | 9.9 |

| Masters | 14 | 3.9 |

| Doctoral | 2 | 0.6 |

| School: | ||

| Agriculture | 25 | 6.9 |

| Education | 67 | 18.5 |

| Environmental science | 45 | 12.4 |

| Health Sciences | 39 | 10.7 |

| Human& social sciences | 49 | 13.5 |

| Law | 17 | 4.7 |

| Management sciences | 63 | 17.4 |

| Maths and natural sciences | 58 | 16.0 |

| Source of income: | ||

| Bursary | 294 | 81.0 |

| Parents | 36 | 9.9 |

| Self-employed | 6 | 1.7 |

| Both parents and bursary | 27 | 7.4 |

| Food Items | Daily | Once Per Week | Twice Per Week | Three Times Per Week | Four Times or More | Not at All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Fast food or restaurant | 20 | 5.5 | 153 | 42.1 | 42 | 11.6 | 15 | 4.1 | 21 | 5.8 | 112 | 30.9 |

| Fruits and vegetables | 79 | 21.8 | 75 | 20.7 | 54 | 14.9 | 63 | 17.4 | 79 | 21 | 13 | 3.6 |

| Fish, chicken, eggs, lean meat | 101 | 27.8 | 43 | 11.8 | 27 | 7.4 | 67 | 18.3 | 121 | 33.3 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Beans | 9 | 2.5 | 149 | 41 | 25 | 12.7 | 12 | 3.3 | 13 | 3.6 | 136 | 36.9 |

| Processed food | 31 | 8.5 | 103 | 28.4 | 70 | 19.3 | 37 | 10.2 | 22 | 6.1 | 100 | 27.5 |

| Milk, mass, or yoghurt | 66 | 18.2 | 92 | 25.3 | 63 | 17.4 | 39 | 10.7 | 82 | 14.3 | 51 | 14 |

| Soft drinks, juice, and energised drinks | 94 | 25 | 68 | 18.7 | 59 | 16.3 | 54 | 16.3 | 63 | 17.4 | 25 | 6.9 |

| Variables | BMI Classification | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal | Overweight/obese | ||

| Soft drinks, juice, and energised drinks | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | 0.006 ** |

| Daily | 10 (10.6) | 61 (64.9) | 23 (24.5) | |

| Once a week | 4 (5.9) | 39 (57.4) | 25 (36.8) | |

| Twice a week | 0 (0) | 40 (67.8) | 19 (32.2) | |

| Three and more per week | 15 (4.1) | 81 (69.8) | 27 (23.3) | |

| Not at all | 1 (3.8) | 10 (38.5) | 15 (57.7) | |

| Variables | WHR | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | At risk | ||

| Frequency of eating in restaurants per week | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Daily | 20 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0.038 * |

| Once per week | 143 (93.5) | 10 (6.5) | |

| Twice and more | 71 (91) | 7 (9) | |

| Not at all | 111 (99.1) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Frequency of eating processed food per week | |||

| Daily | 31 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0.007 ** |

| Once per week | 91 (88.3) | 12 (11.7) | |

| Twice per week | 68 (97.1) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Three times and more per week | 58 (98.3) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Not at all | 97 (97) | 3 (3) | |

| Frequency of eating milk, mass, or yoghurt per week | |||

| Daily | 64 (97) | 2 (3) | |

| Once per week | 92 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Twice per week | 59 (93.7) | 4 (6.3) | 0.013 * |

| Three time and more per week | 81 (89) | 10 (11) | |

| Not at all | 49 (96.1) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Frequancy of eating beans per week | |||

| Daily | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Once per week | 139 (93.3) | 10 (6.7) | 0.000 *** |

| Twice per week | 46 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Three time and more per week | 22 (91.7) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Not at all | 132 (97.8) | 3 (2.2) | |

| Dietary Factor | Not at All | Once Weekly | Twice Weekly | 3+ Times Weekly | Daily | χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meals per day | - | - | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 3.06 | 0.217 |

| Eating in Restaurants | 0.77 a | 0.78 a | 0.80 b | - | 0.78 a,b | 15.54 | 0.001 ** |

| Fruit intake | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.79 | - | 0.78 | 3.73 | 0.292 |

| Protein foods | 0.77 a,b | 0.75 a | 0.80 a,b | 0.79 b | 0.78 a,b | 12.23 | 0.016 * |

| Beans/legumes | 0.78 a | 0.78 a | 0.80 a | 0.77 a | 0.83 b | 16.58 | 0.002 ** |

| Processed foods | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.926 |

| Dairy products | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 7.26 | 0.123 |

| Sweetened beverages | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 6.13 | 0.190 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mushaphi, L.F.; Mokoena, K.; Mugware, A.; Bere, A.; Motadi, S.A. Dietary Practices and Anthropometric Status of the Rural University Students in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060936

Mushaphi LF, Mokoena K, Mugware A, Bere A, Motadi SA. Dietary Practices and Anthropometric Status of the Rural University Students in Limpopo Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060936

Chicago/Turabian StyleMushaphi, Lindelani F., Khutso Mokoena, Anzani Mugware, Alphonce Bere, and Selekane Ananias Motadi. 2025. "Dietary Practices and Anthropometric Status of the Rural University Students in Limpopo Province, South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060936

APA StyleMushaphi, L. F., Mokoena, K., Mugware, A., Bere, A., & Motadi, S. A. (2025). Dietary Practices and Anthropometric Status of the Rural University Students in Limpopo Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060936