Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Cultural Study in Colombian and Mexican Adolescents with Eating Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis Plan

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| ASEBA | Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment |

| EDs | Eating Disorders |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Checklist |

| YSR | Youth Self-Report |

| EAT-26 | Eating Attitudes Test-26 |

References

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth-a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorós-Reche, V.; Belzunegui-Pastor, A.; Hurtado, G.; Espada, J.P. Emotional problems in Spanish children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Clínica Salud 2022, 33, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Mazidi, M.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Kirwan, R.; Zhou, H.; Yan, N.; Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y.T. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 279, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argumedos De La Ossa, C.; Solórzano Santos, M.C. Conductas antisociales y delictivas en una muestra de adolescentes colombianos entre 11 y 17 años pertenecientes a una región de la Costa Caribe. Logos Cienc. Tecnol. 2024, 16, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Se Acaba la Emergencia Por la Pandemia, Pero la COVID-19 Continúa. 2023. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/6-5-2023-se-acaba-emergencia-por-pandemia-pero-covid-19-continua (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Achenbach, T.M.; Ezpeleta, L. Modelos de clasificación en psicopatología. In Psicopatología del Desarrollo; Difusora Larousse: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles; University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.T.; Atkinson, E.A.; Davis, H.A.; Riley, E.N.; Oltmanns, J.R. The General Factor of Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 16, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Rogantini, C.; Provenzi, L.; Borgatti, R. Rating behavioral problems in adolescent eating disorders: Parent-child differences. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Negrete, M.; Arhuis-Inca, W.; Pérez-Morán, G.; Coronado-Fernández, J.; Cjuno, J. Síntomas de ansiedad, conductas agresivas y trastornos alimentarios en adolescentes del norte de Perú. Apunt. Univ. 2022, 12, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Autor: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa Acosta, C.; Moreno Méndez, J.H. Relación entre problemas alimenticios y comportamientos internalizados en adolescentes: Revisión de alcance. Rev. Criterios 2025, 32, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-García, G.; Gómez-Peresmitré, G.; Velasco Ariza, V.; Platas Acevedo, S.; Áramburo Vizcarra, V. Riesgo de anorexia y bulimia en función de la ansiedad y la edad de la pubertad en universitarios de Baja California-México. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2014, 5, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Maunder, K.; Lehmann, O.; McKeown, M.; McNicholas, F. The long-term impact of Covid-19 on presentations to a specialist child & adolescent eating disorder program. Res. Sq. 2022, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.; Pietrobom, T.; Mihic, J.; Caetano, J.; Mari, J.; Sanchez, Z.M. Externalizing and internalizing problems as predictors of alcohol-related harm and binge drinking in early adolescence: The role of gender. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobillard, C.L.; Legg, N.K.; Ames, M.E.; Turner, B.J. Support for a transdiagnostic motivational model of self-damaging behaviors: Comparing the salience of motives for binge drinking, disordered eating, and nonsuicidal self-injury. Behav. Ther. 2022, 53, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilsbach, A.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. “What made my eating disorder worse?” The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, R.; Patel, I.; Balkrishnan, R. Risk factors and strategies for prevention of depression, anxiety and eating disorders among adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. Glob. Health J. 2023, 7, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeros Ortiz, S.; Caro Molano, J.; López de Mesa, C. Factores de riesgo de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en jóvenes escolarizados en Cundinamarca (Colombia). Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2010, 39, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, E.; Méndez, C.; Jauregui, A. Prevalencia del riesgo de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en una población de estudiantes de secundaria, Bogotá-Colombia. Rev. Med. 2017, 25, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Acuña, L.C.; Franco Zuluaga, A. Behavioural and emotional symptoms of adolescents consulting a specialised eating disorders programme. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2022, 51, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cuevas, B.; Valero-Aguayo, L.; Solano-Martínez, D.; Priore-Molero, C.; Perea-Barba, A.; Afán de Rivera, M. Detección de problemas alimentarios y su relación con hábitos alimentarios en adolescentes. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2020, 10, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto-López, J.; Franco-Paredes, K.; Bautista-Díaz, M.L.; Santoyo Telles, F. Programa de prevención universal para factores de riesgo de trastornos alimentarios en adolescentes mexicanas: Un estudio piloto. Rev. Psicol. Clínica Niños Adolesc. 2022, 9, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Molina, T.J.; Martínez, C.; Bautista-Díaz, M.L. Riesgo para desarrollar interiorización del ideal estético de la delgadez en adolescentes mexicanas. Interdisciplinaria 2021, 38, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Hernández, A.; Bojórquez-Chapela, I.; Hernández-Serrato, M.I.; Unikel-Santoncini, C. Prevalencia de conductas alimentarias de riesgo en adolescentes mexicanos: Ensanut Continua 2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, s96–s101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zancu, A.S.; Diaconu-Gherasim, L.R. Weight stigma and mental health outcomes in early-adolescents. The mediating role of internalized weight bias and body esteem. Appetite 2024, 196, 107276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

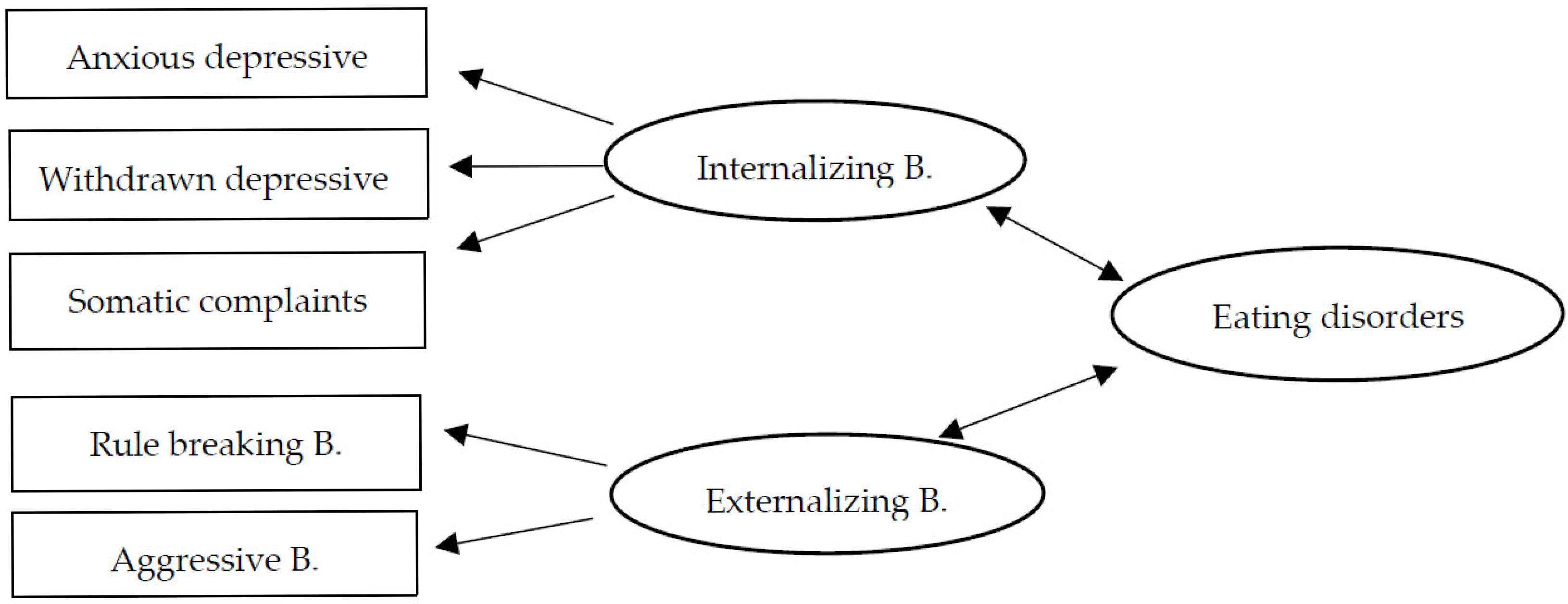

- Moreno Encinas, A.; Moraleda Merino, J.; Graell-Berna, M.; Villa-Asensi, J.R.; Álvarez, T.; Lacruz-Gascón Sepúlveda García, A.R. Modelo de interiorización y exteriorización para explicar el inicio de la psicopatología de los trastornos alimentarios en la adolescencia. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Conduct. 2021, 29, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J. The interaction of race/ethnicity and school-connectedness in presenting internalizing and externalizing behaviors among adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 161, 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, E.; Lewis, V.; Minehan, M.; Joshua, P.R. Knocking on locked doors; a qualitative investigation of parents’ experiences of seeking help for children with eating disorders. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 28, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bustinzar, A.R.; Valdez-Aguilar, M.; Rojo Moreno, L.; Radilla Vázquez, C.C.; Barriguete Meléndez, J.A. Influencias socioculturales sobre la imagen corporal en pacientes mujeres con trastornos alimentarios: Un modelo explicativo. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2023, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Ávila, C.E.; Carpio, N. Introducción a los tipos de muestreo. Alerta 2019, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, N.; Jaimes, S.; Vera, L.A.; Villa, M.C. Características Psicométricas del Cuestionario de Comportamientos Infantiles CBCL en Niños Y Adolescentes Colombianos; Universidad de San Buenaventura: Cartagena, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla, L.A.; Althoff, R.R.; Achenbach, T.M.; Ivanova, M.Y. Effects of society and culture on parent’s ratings of children’s mental health problems in 45 societies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Echavarría, K.; Pardo, A.; Quiñones, Y. Funcionalidad familiar, conductas internalizadas y rendimiento académico en un grupo de adolescentes de la ciudad de Bogotá. Psychologia 2014, 8, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelata-Eguiarte, B.E.; Ávila-García, G.A.; Márquez-Caraveo, M.E. Propiedades psicométricas del Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/6-18) en padres de adolescentes mexicanos. Eureka 2019, 16, 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelata-Eguiarte, B.E.; Márquez-Caraveo, M.E. Estudios de validez del Youth Self Report/11-18 en adolescentes mexicanos. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Aval. Psicol. 2019, 50, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol. Med. 1979, 9, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constaín, G.A.; Ricardo Martínez, C.; Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.A.; Álvarez Gómez, M.; Marín Múnera, C.; Agudelo Acosta, C. Validez y utilidad diagnóstica de la escala EAT-26 para la evaluación del riesgo de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en población femenina de Medellín, Colombia. Aten. Primaria 2014, 46, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Salazar, K.J.; Pineda-García, G. Propiedades psicométricas del Test de Actitudes Alimentarias (EAT-26) en una muestra no clínica de adolescentes. Cuad. Hispanoam. Psicol. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project (2022) Jamovi. (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ferguson, C.J. An Effect Size Primer: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Cascella, C.; Confetto, S.; Piscopo, A.; Loffredo, G.; Golino, A.; Iafusco, D. Disordered eating behaviors among Italian adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Exploring relationships with parents’ eating disorder symptoms, externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and body image problems. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2020, 27, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. The impact of teasing and bullying victimization on disordered eating and body image disturbance among adolescents: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnick, J.L.; Darling, K.E.; West, C.E.; Jones, L.; Jelalian, E. Weight stigma and mental health in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavira, D.A.; Ponting, C.; Ramos, G. The impact of COVID-19 on child and adolescent mental health and treatment considerations. Behav. Res. Ther. 2022, 157, 104169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Frequency (Percentage) | Comparison Analysis | CBCL | YSR | EAT-26 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN-D | AI-D | QS | PI | RR | CA | PE | AN-D | AI-D | QS | PI | RR | CA | PE | |||||

| Colombian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender | Male | 2 (7.7) | Statistic value | −0.656 a | 13.5 b | 10 b | −0.47 a | 13 b | −108 a | −0.914 a | −2.66 a | −1.03 a | −0.703 a | −2.63 a | 9 b | 1.0 b | −2.79 a | −0.396 a |

| Female | 15 (57.7) | p | 0.618 | 0.879 | 0.50 | 0.714 | 0.822 | 0.46 | 0.506 | 0.073 | 0.321 | 0.595 | 0.036 | 0.409 | 0.043 | 0.117 | 0.749 | |

| ES | −0.546 | 0.10 | 0.333 | −0.406 | 0.133 | −0.91 | −0.725 | −1.347 | −0.376 | −0.569 | −1.151 | 0.400 | 0.933 | −1.675 | −0.305 | |||

| Parents’ Gender | Male | 5 (19.2) | Statistic value | −0.989 a | 22.5 b | 27.5 b | −0.819 a | 22 b | 0.06 a | −0.408 a | −21.9 a | −14.5 a | −19.5 a | −23.1 a | 19 b | 25.5 b | −10 a | −0.379 a |

| Female | 12 (46.2) | p | 0.34 | 0.451 | 0.832 | 0.431 | 0.425 | 0.953 | 0.691 | 0.056 | 0.203 | 0.082 | 0.055 | 0.265 | 0.672 | 0.344 | 0.713 | |

| ES | −0.4667 | 0.250 | 0.083 | −0.409 | 0.267 | 0.029 | −0.203 | −11.21 | −0.83 | −0.998 | −12.59 | 0.367 | 0.150 | −0.517 | −0.1903 | |||

| Grade | Sixth | 1 (3.8) | Statistic value | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Seventh | 2 (7.7) | |||||||||||||||||

| Eighth | 0 (0) | p | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Ninth | 5 (19.2) | |||||||||||||||||

| Tenth | 3 (11.5) | ES | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Eleventh | 6 (23.1) | |||||||||||||||||

| Twelfth | 0 (0) | |||||||||||||||||

| Parents’ Occupation | Self-employed | 4 (15.4) | Statistic value | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Employee | 12 (46.2) | p | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Homemaker | 0 (0) | ES | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Other | 1 (3.8) | |||||||||||||||||

| Mexican | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender | Male | 0 (0) | Statistic value | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Female | 9 (34.6) | p | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| ES | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |||

| Parents’ Gender | Male | 2 (7.7) | Statistic value | −1.43 a | 5.50 b | 4.50 b | −1.35 a | 2.50 b | 1.237 a | 1.618 a | −0.219 a | −2.27 a | 0.826 a | 0.107 a | 7 b | 5 b | −0.883 a | 4.17 a |

| Female | 7 (26.9) | p | 0.232 | 0.767 | 0.551 | 0.295 | 0.219 | 0.262 | 0.151 | 0.854 | 0.058 | 0.551 | 0.930 | 1 | 0.659 | 0.435 | 0.112 | |

| ES | −0.945 | 0.214 | 0.357 | −0.989 | 0.643 | 0.661 | 0.930 | −0.187 | −1.281 | 0.787 | 0.099 | 0 | 0.286 | −0.588 | 0.876 | |||

| Grade | Sixth | 1 (3.8) | Statistic value | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Seventh | 1 (3.8) | |||||||||||||||||

| Eighth | 3 (11.5) | p | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Ninth | 1 (3.8) | |||||||||||||||||

| Tenth | 0 (0) | ES | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | |

| Eleventh | 2 (7.7) | |||||||||||||||||

| Twelfth | 1 (3.8) | |||||||||||||||||

| Parents’ Occupation | Self-employed | 2 (7.7) | Statistic value | 0.653 c | 4.86 d | 4.03 d | 1.41 c | 0.275 d | 0.146 c | 0.147 c | 7.25 c | 3.14 c | 1.55 c | 10.74 c | 1.48 d | 0 d | 0.377 c | 1.72 c |

| Employee | 4 (15.4) | p | 0.554 | 0.088 | 0.133 | 0.316 | 0.871 | 0.867 | 0.866 | 0.123 | 0.116 | 0.287 | 0.010 | 0.477 | 1 | 0.701 | 0.288 | |

| Homemaker | 3 (11.5) | ES | 0.165 | 0.6072 | 0.5036 | 0.562 | 0.0344 | 0.165 | 0.165 | NE | −0.833 | −0.528 | 1.613 | 0.1850 | 0 | NE | 0.222 | |

| Variable | M | SD | Comparison Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mex | Col | N | Mex | Col | N | Statistic Value | p | ES | ||

| CBCL | AN-D | 9.63 | 11 | 10.6 | 5.24 | 5.35 | 5.24 | −0.608 a | 0.276 | 0.260 |

| AI-D | 5.13 | 6.65 | 6.16 | 2.95 | 3.77 | 3.54 | 52.5 b | 0.187 | 0.228 | |

| QS | 3.88 | 7.18 | 6.12 | 2.42 | 4.17 | 3.97 | 37 b | 0.037 | 0.456 | |

| PI | 18.6 | 24.8 | 22.8 | 7.91 | 11.7 | 10.9 | −1.555 a | 0.068 | 0.620 | |

| RR | 2 | 5.88 | 4.64 | 1.20 | 4.61 | 4.24 | 39 b | 0.046 | 0.426 | |

| CA | 8.13 | 10.9 | 10 | 4.64 | 5.80 | 5.52 | −1.276 a | 0.110 | 0.525 | |

| PE | 10.1 | 16.8 | 14.6 | 5.38 | 9.90 | 9.16 | −2.167 a | 0.021 | 0.833 | |

| YSR | AN-D | 12.4 | 13.2 | 13 | 2.33 | 5.23 | 4.47 | −0.569 a | 0.287 | 0.213 |

| AI-D | 5.63 | 6.82 | 6.44 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.25 | −0.864 a | 0.201 | 0.368 | |

| QS | 6 | 6.76 | 6.52 | 4.6 | 4.05 | 4.15 | −0.402 a | 0.347 | 0.176 | |

| PI | 24 | 26.8 | 25.9 | 7.23 | 10.3 | 9.37 | −0.790 a | 0.220 | 0.317 | |

| RR | 3.63 | 5.88 | 5.16 | 2.67 | 3.74 | 3.54 | 43 b | 0.075 | 0.368 | |

| CA | 10.5 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 9.47 | 4.60 | 6.38 | 39.5 b | 0.051 | 0.419 | |

| PE | 14.1 | 17.6 | 16.5 | 10.3 | 7.47 | 8.43 | −0.866 a | 0.203 | 0.391 | |

| EAT-26 | 10.6 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 6.92 | 9.10 | 8.58 | −1.173 a | 0.130 | 0.497 | |

| CBCL | YSR | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nac | RL | AN-D | AI-D | QS | PI | RR | CA | PE | AN-D | AI-D | QS | PI | RR | CA | PE |

| Col | NR | 5 (20) | 7 (28) | 6 (24) | 3 (12) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) | 7 (28) | 2 (8) | 7 (28) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 8 (32) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) |

| AR | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 5 (20) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 5 (20) | 10 (40) | 2 (8) | |

| CL | 8 (32) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) | 13 (52) | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | 9 (36) | 10 (40) | 4 (16) | 12 (48) | 16 (64) | 4 (16) | 2 (8) | 14 (56) | |

| Mex | NR | 3 (12) | 5 (20) | 5 (20) | 2 (8) | 8 (32) | 7 (28) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 7 (28) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) |

| AR | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 3 (3) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 4 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | |

| CL | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 5 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 6 (24) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 8 (32) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (16) | |

| Total N | NR | 8 (32) | 12 (48) | 11 (44) | 5 (20) | 17 (68) | 16 (64) | 11 (44) | 2 (8) | 11 (44) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 15 (60) | 9 (36) | 1 (4) |

| AR | 7 (28) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 2 (8) | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 4 (16) | 7 (28) | 8 (32) | 7 (28) | 0 (0) | 5 (20) | 13 (52) | 6 (24) | |

| CL | 10 (40) | 11 (44) | 11 (44) | 18 (72) | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | 10 (40) | 16 (64) | 6 (24) | 15 (60) | 2 (24) | 5 (20) | 3 (12) | 18 (72) | |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | ω2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Model | 703 | 4 | 175.7 | 3.37 | 0.030 | |

| Anxious/Depressed Risk Levels YSR | 206 | 2 | 103.0 | 1.97 | 0.166 | 0.058 |

| Nationality | 124 | 1 | 124.3 | 2.38 | 0.139 | 0.041 |

| Anxious/Depressed Risk Levels YSR ✻ Nationality | 372 | 1 | 372.5 | 7.14 | 0.015 | 0.183 |

| Residuals | 991 | 19 | 52.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno Méndez, J.H.; Rozo Sánchez, M.M.; Maldonado Avendaño, N.; Santacoloma Suárez, A.M.; Vélez Belmonte, J.; Figueroa Hernández, J.A.; Tanus Minutti, S.; León Hernández, R.C. Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Cultural Study in Colombian and Mexican Adolescents with Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060932

Moreno Méndez JH, Rozo Sánchez MM, Maldonado Avendaño N, Santacoloma Suárez AM, Vélez Belmonte J, Figueroa Hernández JA, Tanus Minutti S, León Hernández RC. Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Cultural Study in Colombian and Mexican Adolescents with Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060932

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno Méndez, Jaime Humberto, María Margarita Rozo Sánchez, Natalia Maldonado Avendaño, Andrés Mauricio Santacoloma Suárez, Julieta Vélez Belmonte, Jesús Adrián Figueroa Hernández, Stephanie Tanus Minutti, and Rodrigo César León Hernández. 2025. "Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Cultural Study in Colombian and Mexican Adolescents with Eating Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060932

APA StyleMoreno Méndez, J. H., Rozo Sánchez, M. M., Maldonado Avendaño, N., Santacoloma Suárez, A. M., Vélez Belmonte, J., Figueroa Hernández, J. A., Tanus Minutti, S., & León Hernández, R. C. (2025). Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: A Cross-Cultural Study in Colombian and Mexican Adolescents with Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060932