The Contribution of Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits to Mental and Behavioral Health Among a Diverse Group of Young People

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health Indicators

2.2.2. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits

2.2.3. Demographic Characteristics

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Classes of SDOH Deficits

3.2. SDOH and Health Indicators by Different Marginalized Identities

3.3. Youth Social Identity Characteristics and Health Indicators Across Classes

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Health Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daly, M. Prevalence of depression among adolescents in the US from 2009 to 2019: Analysis of trends by sex, race/ethnicity, and income. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Hou, D.; Huang, X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 912441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Pastore, M.; Palladino, B.E.; Reime, B.; Warth, P.; Menesini, E. The development of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) during adolescence: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, F.; Amini, J.; Sinyor, M.; Schaffer, A.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Mitchell, R.H. Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowsky, I.W.; Ireland, M.; Resnick, M.D. Health status and behavioral outcomes for youth who anticipate a high likelihood of early death. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e81–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Lu, W. Cumulative health risk behaviors and adolescent suicide: The moderating role of future orientation. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 1086–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.-W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.-F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberg, A.; Rice, T. Depression and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Med. Clin. 2023, 107, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.M.; Yule, A.M.; Schiff, D.; Bagley, S.M.; Wilens, T.E. Risk factors for drug overdose in young people: A systematic review of the literature. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshin, L.; Hausmann-Stabile, C.; Meza, J.I.; Polanco-Roman, L.; Bettis, A.H.; Reyes-Portillo, J.; Benton, T.D. Suicide and suicidal behaviors among minoritized youth. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2022, 31, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, P.; LaBrenz, C.A.; Asiedua-Baiden, G.; Muehlenkamp, J.J. Examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents: Findings from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 125, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Beletsky, L.; Jordan, A. Surging racial disparities in the US overdose crisis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2022, 179, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinzo, P.N.; Martins, S.S. Racial/ethnic trends in opioid and polysubstance opioid overdose mortality in adolescents and young adults, 1999–2020. Addict. Behav. 2024, 156, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.; Godvin, M.; Shover, C.L.; Gone, J.P.; Hansen, H.; Schriger, D.L. Trends in drug overdose deaths among US adolescents, January 2010 to June 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 1398–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, T.A.; Bettis, A.H.; Barnicle, S.C.; Wang, S.B.; Fox, K.R. Disclosure of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors across sexual and gender identities. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021050255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, E.H.; Peters, J.R.; Brick, L.A.; Killam, M.A.; Yen, S. A daily diary study of minority stressors, suicidal ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury ideation, and affective mechanisms among sexual and gender minority youth. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2023, 132, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, M.T.; Davis, C.G. Out of sight but on my mind: Distal stressors, identity concealment, proximal stress, and mental health among sexual or gender minorities. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.J.; Michaels, M.S.; Bliss, W.; Rogers, M.L.; Balsam, K.F.; Joiner, T. Suicidal ideation in transgender people: Gender minority stress and interpersonal theory factors. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Pachkowski, M.C.; Shahnaz, A.; May, A.M. The three-step theory of suicide: Description, evidence, and some useful points of clarification. Prev. Med. 2021, 152, 106549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniuka, A.R.; Nanney, E.M.; Robertson, R.; Hoff, R.; Smith, M.; Bowling, J.; Basinger, E.D.; Dahl, A.A.; Cramer, R.J. A grounded theory of sexual and gender minority suicide risk: The sexual and gender minority suicide risk and protection model. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2024. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbach, J.T.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Bagwell, M.; Dunlap, S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prev. Sci. 2014, 15, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, M.C.; Arriaga, A.S.; Gobble, T.; Wille, L. Stress and substance use among sexual and gender minority individuals across the lifespan. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 10, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.; Butler, C.; Cooper, K. Gender minority stress in trans and gender diverse adolescents and young people. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrenholtz, M.S.; Nicholas, J.; Sacco, A.; Bresin, K. Sexual and gender minority stress in nonsuicidal self-injury engagement: A meta-analytic review. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2025, 55, e13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J.; Abel, T.; Campostrini, S.; Cook, S.; Lin, V.K.; McQueen, D.V. The social determinants of health: Time to re-think? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr. Clin. 2016, 63, 985–997. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.; Phillips, G.; Corcoran, P.; Platt, S.; McClelland, H.; O’Driscoll, M.; Griffin, E. The social determinants of suicide: An umbrella review. Epidemiol. Rev. 2025, 47, mxaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Adler, N.E.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Chin, M.H.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Navas-Acien, A.; Thornton, P.L.; Haire-Joshu, D. Social determinants of health and diabetes: A scientific review. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer-Kerwick, M.; Cox, K.; Purohit, I.; Watkins, S.C. The role of social determinants of health in mental health: An examination of the moderating effects of race, ethnicity, and gender on depression through the all of us research program dataset. PLOS Ment. Health 2024, 1, e0000015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, E.R.; Goldbach, J.T.; Blosnich, J.R. Social determinants of sexual and gender minority mental health. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2022, 9, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, P.; Campbell, J.A.; Harris, M.; Egede, L.E. Racial/ethnic differences in social determinants of health and health outcomes among adolescents and youth ages 10–24 years old: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wu, L. Social determinants on suicidal thoughts among young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, P.J.; Shin, J.; Kwak, H.R.; Lee, J.; Jester, D.J.; Bandara, P.; Kim, J.Y.; Moutier, C.Y.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Oquendo, M.A. Social determinants of health and suicide-related outcomes: A review of meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, R.A.; Jiang, R.; Bank, M.; Quarles, J.; Patel, M.; Sun, Y.; Hartman, H.; Zaorsky, N.G.; Jia, A.; Shoag, J. Evaluation of social determinants of health and prostate cancer outcomes among black and white patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2250416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, R.; Forman, R.; Mossialos, E.; Nasir, K.; Kulkarni, A. Social determinants of disparities in mortality outcomes in congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 829902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder, M.E.; Kulie, P.; Jensen, C.; Levett, P.; Blanchard, J.; Dominguez, L.W.; Portela, M.; Srivastava, A.; Li, Y.; McCarthy, M.L. The impact of social determinants of health on medication adherence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, T.; Milis, S.-L.; Vanthomme, K.; Vandenheede, H. The social determinants of health-related quality of life among people with chronic disease: A systematic literature review. Qual. Life Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure-Child Age 11–17. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/assessment-measures (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- National Data Archive. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. National Insttute of Mental Health. Available online: https://nda.nih.gov/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Turner, H.A.; Butler, M.J. Direct and indirect effects of childhood adversity on depressive symptoms in young adults. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, C.; Reise, S.P.; Chorpita, B.F.; Ale, C.; Regan, J.; Young, J.; Higa-McMillan, C.; Weisz, J.R. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Short Version: Scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaufus, L.; Verlinden, E.; Van Der Wal, M.; Kösters, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Chinapaw, M. Psychometric evaluation of two short versions of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Social Needs Screening Tool. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/everyone_project/hops19-physician-form-sdoh.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Florin, P.; Rich, R.C.; Wandersman, A.; Chavis, D.M. Participation and the social and physical environment of residential blocks: Crime and community context. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 83–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Espelage, D.L.; Mitchell, K.J. The co-occurrence of Internet harassment and unwanted sexual solicitation victimization and perpetration: Associations with psychosocial indicators. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S31–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banyard, V.; Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L. Exposure to self-directed violence: Understanding intention to help and helping behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V.; Rousseau, D.; Shockley McCarthy, K.; Stavola, J.; Xu, Y.; Hamby, S. Community-level characteristics associated with resilience after adversity: A scoping review of research in urban locales. Trauma Violence Abus. 2025, 26, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Waygood, E.O.D.; Fullan, J. Subjective well-being of Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of the social and physical environment and healthy movement behaviours. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceatha, N.; Koay, A.C.; Buggy, C.; James, O.; Tully, L.; Bustillo, M.; Crowley, D. Protective factors for LGBTI+ youth wellbeing: A scoping review underpinned by recognition theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard-Garris, N.; Boyd, R.; Kan, K.; Perez-Cardona, L.; Heard, N.J.; Johnson, T.J. Structuring poverty: How racism shapes child poverty and child and adolescent health. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, S108–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Brady, D.; Parolin, Z.; Williams, D.T. The enduring significance of ethno-racial inequalities in poverty in the US, 1993–2017. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 1049–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.S.; Keyes, K.M.; Branas, C.; Cerdá, M.; Gruenwald, P.; Hasin, D. Understanding the differential effect of local socio-economic conditions on the relation between prescription opioid supply and drug overdose deaths in US counties. Addiction 2023, 118, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, D.S.; Schleimer, J.P.; Keyes, K.M.; Branas, C.C.; Cerdá, M.; Gruenwald, P.; Hasin, D. Social and economic determinants of drug overdose deaths: A systematic review of spatial relationships. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, A.; Lund, C.; Araya, R.; Hessel, P.; Sanchez, J.; Garman, E.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Diaz, Y.; Avendano-Pabon, M. The relationship between multidimensional poverty, income poverty and youth depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional evidence from Mexico, South Africa and Colombia. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e006960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.N.; Dunkwu, L.; Tchangalova, N.; McFarlane, S. Associations between policy and health for sexual and gender minority youth in the United States: A scoping review. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 77, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 13–17 years | 2835 | 56.9 |

| 18–22 years | 2146 | 43.1 |

| Mean age (SD) | --- | 17.4 (2.2) |

| Sex at birth | ||

| Male | 1868 | 37.5 |

| Female | 2931 | 58.8 |

| Intersex | 46 | 0.9 |

| Missing | 136 | 2.7 |

| Gender identity a | ||

| Exclusively cisgender | 3074 | 61.7 |

| Transgender | 751 | 15.1 |

| Non-binary, genderqueer, genderfluid, pangender, indigenous | 1206 | 24.2 |

| Agender | 204 | 4.1 |

| Gender variant, questioning | 348 | 7.0 |

| Missing | 85 | 1.7 |

| Sexual identity a | ||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 2005 | 40.3 |

| Gay, lesbian | 674 | 13.5 |

| Bisexual, queer, polysexual, demisexual | 1927 | 38.7 |

| Asexual, no sexuality | 406 | 8.1 |

| Questioning, mostly heterosexual, no labels | 249 | 5.0 |

| Missing | 64 | 1.3 |

| Race a | ||

| White | 3711 | 74.5 |

| Black or African American | 557 | 11.2 |

| Asian | 572 | 11.5 |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 56 | 1.1 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 217 | 4.4 |

| Missing | 394 | 7.9 |

| Hispanic or Latino origin (any race) | ||

| No | 3858 | 77.5 |

| Yes | 1071 | 21.5 |

| Missing | 52 | 1.0 |

| Type of community | ||

| Small town or rural area | 1470 | 29.5 |

| Suburban area next to a city | 2462 | 49.4 |

| Urban or city area | 958 | 19.2 |

| Missing | 91 | 1.8 |

| Family income | ||

| Lower than the average family | 1346 | 27.0 |

| About the same as the average family | 2279 | 45.7 |

| Higher than the average family | 1174 | 23.6 |

| Missing | 182 | 3.7 |

| Class | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | AICc | CAIC | Entropy | VLMR | p > VLMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −27,6225.67 | 55,265.34 | 55,330.48 | 55,265.39 | 55,340.48 | --- | --- | --- |

| 2 | −25,095.98 | 50,233.96 | 50,370.74 | 50,234.15 | 50,391.74 | 0.78 | 5053.38 | <0.001 |

| 3 | −24,863.51 | 49,791.02 | 49,999.45 | 49,791.45 | 50,031.45 | 0.64 | 464.94 | <0.001 |

| 4 | −24,722.11 | 49,530.22 | 49,810.30 | 49,530.99 | 49,853.30 | 0.66 | 282.80 | <0.001 |

| 5 | −24,686.24 | 49,480.48 | 49,832.20 | 49,481.68 | 49,886.20 | 0.70 | 71.75 | <0.001 |

| 6 | −24,665.82 | 49,461.63 | 49,885.00 | 49,463.38 | 49,950.00 | 0.62 | 40.85 | 0.16 |

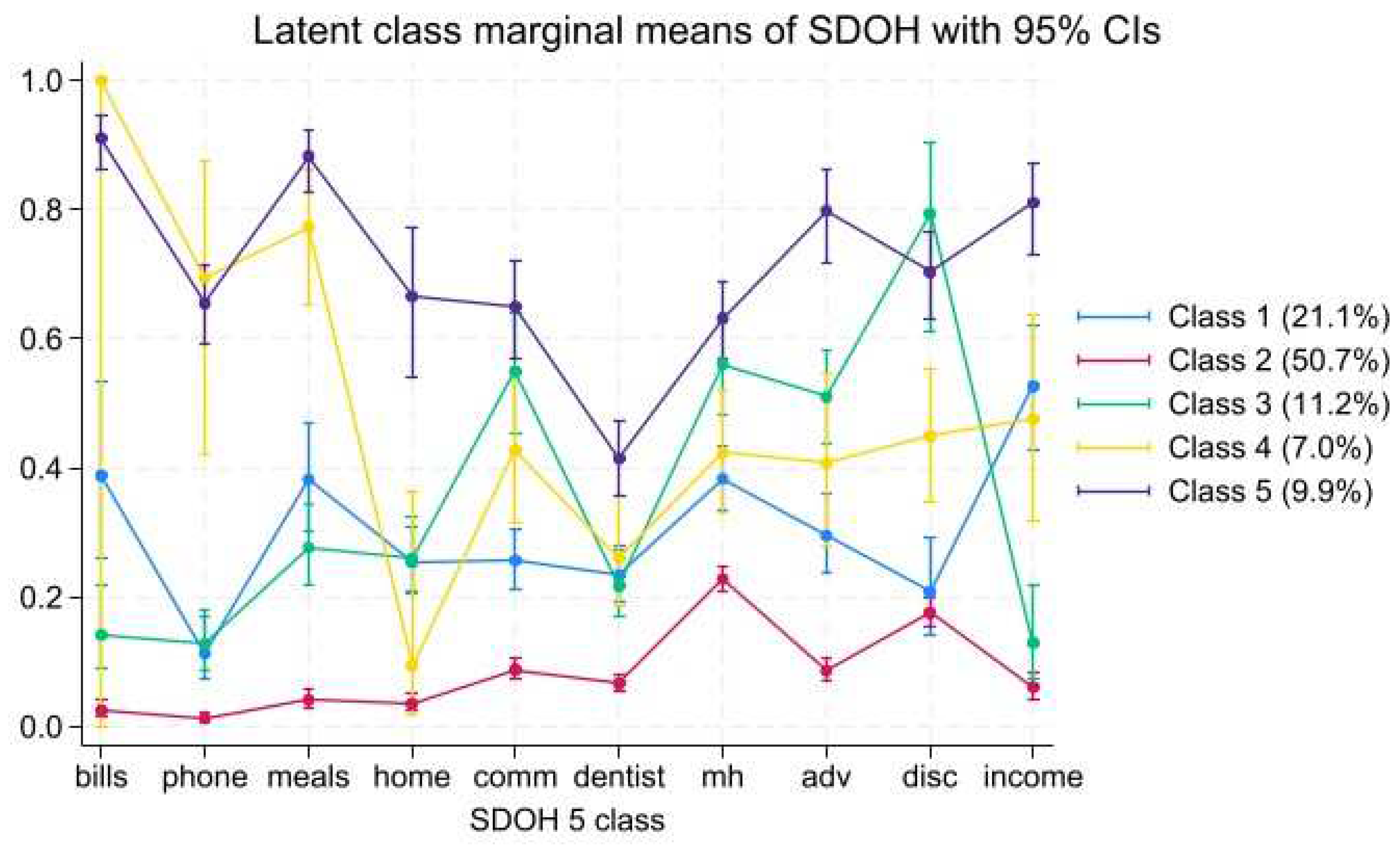

| Characteristic | Class 1 Economic Instability (n = 931) | Class 2 Low Overall SDOH Deficits (n = 2760) | Class 3 High Social SDOH Deficits (n = 454) | Class 4 High Economic SDOH Deficits (n = 339) | Class 5 High Overall SDOH Deficits (n = 497) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Margin (SE) | Margin (SE) | Margin (SE) | Margin (SE) | Margin (SE) | |

| Type of SDOH deficit | |||||

| Economic instability | |||||

| Not enough money to pay the bills | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.02 (0.2) | 0.14 (0.03) | 1.00 (0.001) | 0.91 (0.02) |

| Cell phone turned off | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.65 (0.12) | 0.65 (0.03) |

| Food insecurity | 0.38 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.28 (0.03) | 0.88 (0.05) | 0.88 (0.02) |

| Low income | 0.53 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.47 (0.08) | 0.81 (0.03) |

| Social context | |||||

| Non-victimization adversity | 0.29 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.51 (0.04) | 0.41 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.04) |

| Discrimination | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.79 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.05) | 0.70 (0.03) |

| Healthcare | |||||

| Barriers to mental health care | 0.38 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.56 (0.04) | 0.42 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.03) |

| 2+ years since seeing dentist | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.26 (0.04) | 0.41 (0.03) |

| Neighborhood and built environment | |||||

| Home condition problems | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.67 (0.06) |

| Neighborhood disorder | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.55 (0.05) | 0.43 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.04) |

| All Participants (N = 4981) | Female Assigned at Birth (n = 2931) | Sexual Minority Identity (n = 2909) | Gender Minority Identity (n = 1814) | Black Race (n = 557) | American Indian or Alaska Native Race (n = 217) | Lives in Rural Area (n = 1470) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Type of SDOH | |||||||

| Economic instability | |||||||

| Not enough money to pay the bills | 1349 (27.1) | 839 (28.6) | 850 (29.2) | 559 (30.8) | 208 (37.3) | 99 (45.6) | 444 (30.2) |

| Cell phone turned off | 788 (15.8) | 475 (15.2) | 494 (17.0) | 335 (18.5) | 168 (30.2) | 72 (33.2) | 283 (19.3) |

| Food insecurity | 1366 (27.4) | 833 (28.4) | 898 (30.9) | 596 (32.9) | 218 (39.1) | 99 (45.6) | 434 (29.5) |

| Low income | 1346 (27.0) | 795 (27.1) | 859 (29.5) | 561 (30.9) | 191 (34.3) | 91 (41.9) | 443 (30.1) |

| Social context | |||||||

| Non-victimization adversity | 1349 (27.1) | 827 (28.2) | 953 (32.8) | 669 (36.9) | 166 (29.8) | 113 (52.1) | 454 (30.9) |

| Discrimination | 1610 (32.3) | 941 (32.1) | 1132 (38.9) | 843 (46.5) | 200 (35.9) | 118 (54.4) | 526 (35.8) |

| Healthcare | |||||||

| Barriers to mental health care | 1753 (35.2) | 1132 (38.6) | 1204 (41.4) | 824 (45.4) | 210 (37.7) | 86 (39.6) | 527 (35.9) |

| 2+ years since seeing dentist | 829 (16.6) | 470 (16.0) | 533 (18.3) | 368 (20.3) | 131 (23.5) | 48 (22.1) | 253 (17.2) |

| Neighborhood and built environment | |||||||

| Home condition problems | 864 (17.3) | 544 (18.6) | 592 (20.3) | 401 (22.1) | 102 (18.3) | 63 (29.0) | 318 (21.6) |

| Neighborhood disorder | 1269 (25.5) | 786 (26.8) | 843 (29.0) | 571 (31.5) | 184 (33.0) | 95 (43.8) | 334 (22.7) |

| Average number of SDOH deficits | 2.51 (2.3) | 2.61 (2.4) | 2.87 (2.4) | 3.16 (2.5) | 3.19 (2.4) | 4.07 (2.7) | 2.73 (2.4) |

| Health indicators | |||||||

| Suicide attempt (lt) | 1413 (28.4) | 904 (30.8) | 1085 (37.3) | 806 (44.4) | 153 (27.5) | 97 (44.7) | 431 (29.3) |

| Thoughts of suicide (lt) | 3911 (78.5) | 2366 (80.7) | 2555 (87.8) | 1669 (92.0) | 413 (74.1) | 180 (82.9) | 1160 (78.9) |

| Thoughts of suicide (py) | 2799 (56.2) | 1740 (59.4) | 1845 (63.4) | 1227 (67.6) | 266 (47.8) | 142 (65.4) | 847 (57.6) |

| Drug overdose (lt) | 378 (7.6) | 267 (9.1) | 308 (10.6) | 229 (12.6) | 40 (7.2) | 31 (14.3) | 119 (8.1) |

| Alcohol use (past 2 weeks) | 974 (19.5) | 537 (18.3) | 627 (21.5) | 363 (20.0) | 74 (13.3) | 42 (19.3) | 280 (19.1) |

| NSSI (lt) | 3914 (78.6) | 2409 (82.2) | 2553 (87.8) | 1657 (91.3) | 414 (74.3) | 183 (84.3) | 1177 (80.1) |

| NSSI (py) | 3259 (65.4) | 2031 (69.3) | 2204 (75.8) | 1473 (81.2) | 340 (61.0) | 160 (73.7) | 1006 (68.4) |

| Likelihood of living to age 35 (% (SD)) | 75.6 (26.4) | 74.5 (26.9) | 69.1 (27.7) | 63.5 (28.7) | 77.2 (24.2) | 63.6 (30.1) | 72.7 (27.7) |

| Depression (M (SD)) | 28.9 (14.7) | 31.0 (14.6) | 33.0 (14.1) | 35.6 (13.9) | 28.5 (14.5) | 34.7 (15.9) | 30.1 (14.7) |

| Characteristic | Class 1 Economic Instability n (%) | Class 2 Low Overall SDOH Deficits n (%) | Class 3 High Social SDOH Deficits n (%) | Class 4 High Economic SDOH Deficits n (%) | Class 5 High Overall SDOH Deficits n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | ||||||

| Mean age | 17.95 | 17.26 a | 17.01 a | 17.58 c | 17.76 a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Age category | ||||||

| 13–17 years | 446 (47.9) | 1662 (60.2) a | 289 (63.7) a | 189 (55.7) a,c | 249 (50.1) b,c | <0.001 |

| 18–22 years | 485 (52.1) | 1098 (39.8) | 165 (36.3) | 150 (44.3) | 248 (49.9) | |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||

| Male | 354 (38.8) | 1123 (41.5) | 138 (32.2) a,b | 110 (34.2) a,b | 143 (30.2) a,b | <0.001 |

| Female | 556 (60.9) | 1573 (58.1) | 280 (65.3) | 206 (64.0) | 316 (66.7) | |

| Intersex | 3 (0.3) | 11 (0.4) | 11 (2.6) | 6 (1.9) | 15 (3.2) | |

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Cisgender | 602 (66.7) | 1861 (69.6) a | 186 (42.9) a,b | 192 (60.6) b,c | 212 (44.4) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Transgender | 61 (6.8) | 221 (8.3) | 62 (14.3) | 29 (9.1) | 69 (14.5) | |

| Nonbinary | 153 (17.0) | 352 (13.2) | 107 (24.7) | 62 (19.6) | 123 (25.8) | |

| Agender | 29 (3.2) | 83 (3.1) | 22 (5.1) | 9 (2.8) | 27 (5.7) | |

| Questioning | 57 (6.3) | 156 (5.8) | 57 (13.1) | 25 (7.9) | 46 (9.6) | |

| Any gender minority | ||||||

| No | 623 (66.9) | 1911 (69.3) | 199 (43.8) a,b | 209 (61.7) b,c | 224 (45.1) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Yes | 308 (33.1) | 848 (30.7) | 255 (56.2) | 130 (38.3) | 273 (54.9) | |

| Sexual identity | ||||||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 375 (41.5) | 1260 (46.6) a | 103 (23.4) a,b | 129 (39.2) b,c | 124 (25.9) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Gay or lesbian | 102 (11.3) | 298 (11.0) | 76 (17.3) | 33 (10.0) | 69 (14.4) | |

| Bisexual | 311 (34.4) | 799 (29.5) | 197 (44.8) | 128 (38.9) | 227 (47.5) | |

| Asexual | 69 (7.6) | 184 (6.8) | 25 (5.7) | 18 (5.5) | 33 (6.9) | |

| Questioning | 47 (5.2) | 164 (6.1) | 39 (8.9) | 21 (6.4) | 25 (5.2) | |

| Any sexual minority | ||||||

| No | 396 (42.5) | 1295 (46.9) a | 112 (24.7) a,b | 138 (40.7) b,c | 131 (26.4) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Yes | 535 (57.5) | 1465 (53.1) | 342 (75.3) | 201 (59.3) | 366 (73.6) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 695 (74.7) | 2098 (76.0) | 338 (74.5) | 216 (63.7) a,b,c | 364 (73.2) d | <0.001 |

| Black | 121 (13.0) | 227 (8.2) a | 52 (11.5) b | 74 (21.8) a,b,c | 83 (16.7) b,c | <0.001 |

| Asian | 89 (9.6) | 385 (13.9) a | 47 (10.3) b | 22 (6.5) b | 29 (5.8) a,b,c | <0.001 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 45 (4.8) | 64 (2.3) a | 28 (6.2) b | 25 (7.4) b | 55 (11.1) a,b,c | <0.001 |

| Any race minority | ||||||

| No | 686 (73.7) | 2094 (75.9) | 333 (73.3) | 228 (67.3) a,b | 342 (68.8) a,b | <0.001 |

| Yes | 245 (26.3) | 666 (24.1) | 121 (26.7) | 111 (32.7) | 155 (31.2) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | ||||||

| No | 683 (73.4) | 2259 (81.9) a | 348 (76.7) b | 254 (74.9) b | 366 (73.6) b | <0.001 |

| Yes | 248 (26.6) | 501 (18.1) | 106 (23.3) | 85 (25.1) | 131 (26.4) | |

| Type of community | ||||||

| Rural | 298 (32.5) | 744 (27.2) a | 136 (30.5) b | 116 (37.4) b,c | 176 (36.3) b,c | <0.001 |

| Suburban | 393 (42.9) | 1560 (57.1) | 220 (49.3) | 109 (35.2) | 180 (37.1) | |

| Urban | 226 (24.7) | 428 (15.7) | 90 (20.2) | 85 (27.4) | 129 (26.6) | |

| Health indicators | ||||||

| Suicide attempt (lt) | 272 (29.2) | 545 (19.7) a | 228 (50.2) a,b | 106 (31.3) b,c | 262 (52.7) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Thoughts of suicide (lt) | 766 (82.3) | 2014 (73.0) a | 427 (94.1) a,b | 251 (74.0) a,c | 453 (91.1) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Thoughts of suicide (py) | 527 (56.6) | 1408 (51.0) a | 324 (71.4) a,b | 187 (55.2) c | 353 (71.0) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Drug overdose (lt) | 61 (6.55) | 125 (4.5) a | 66 (14.5) a,b | 35 (10.3) a,b | 91 (18.3) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use (past 2 weeks) | 200 (21.5) | 470 (17.0) a | 91 (20.0) | 69 (20.3) | 144 (29.0) a,b,c,d | <0.001 |

| NSSI (lt) | 758 (81.4) | 2027 (73.4) a | 417 (91.9) a,b | 261 (77.0) c | 451 (90.7) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| NSSI (py) | 620 (66.6) | 1635 (59.2) a | 374 (82.4) a,b | 220 (64.9) b,c | 410 (82.5) a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Likelihood of living to age 35 (%) | 75.95 | 81.46 a | 62.09 a,b | 70.77 a,b,c | 58.45 a,b,d | <0.001 |

| Depression (M) | 28.76 | 24.55 a | 39.80 a,b | 32.24 a,b,c | 41.76 a,b,d | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitchell, K.J.; Banyard, V.; Colburn, D. The Contribution of Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits to Mental and Behavioral Health Among a Diverse Group of Young People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071013

Mitchell KJ, Banyard V, Colburn D. The Contribution of Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits to Mental and Behavioral Health Among a Diverse Group of Young People. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071013

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitchell, Kimberly J., Victoria Banyard, and Deirdre Colburn. 2025. "The Contribution of Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits to Mental and Behavioral Health Among a Diverse Group of Young People" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071013

APA StyleMitchell, K. J., Banyard, V., & Colburn, D. (2025). The Contribution of Social and Structural Determinants of Health Deficits to Mental and Behavioral Health Among a Diverse Group of Young People. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071013