Relationships Between Misinformation Variables and Nutritional Health Strategies: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

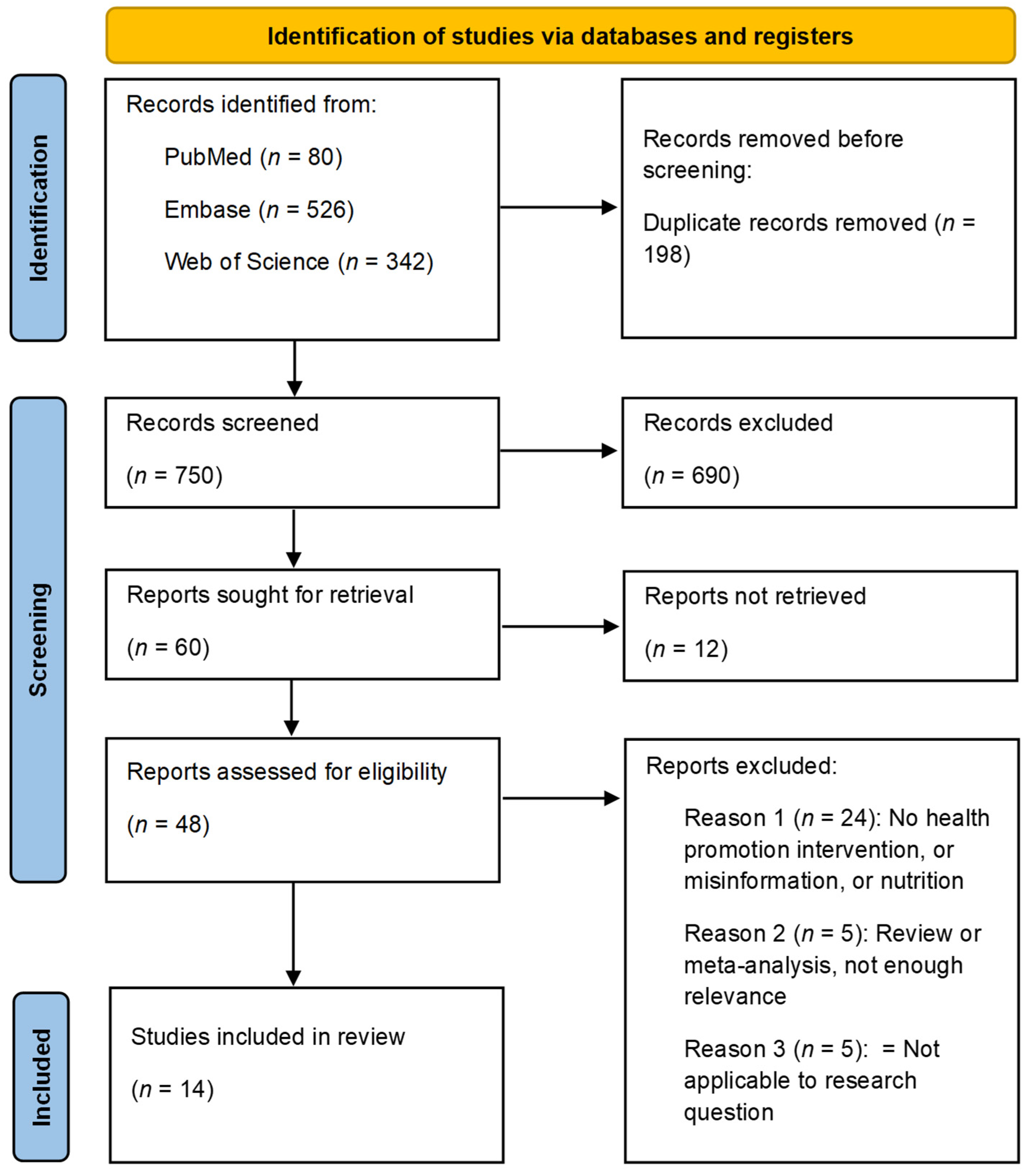

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. The Studies’ Aims

3.2. Study Designs and Methods

3.3. Populations and Samples

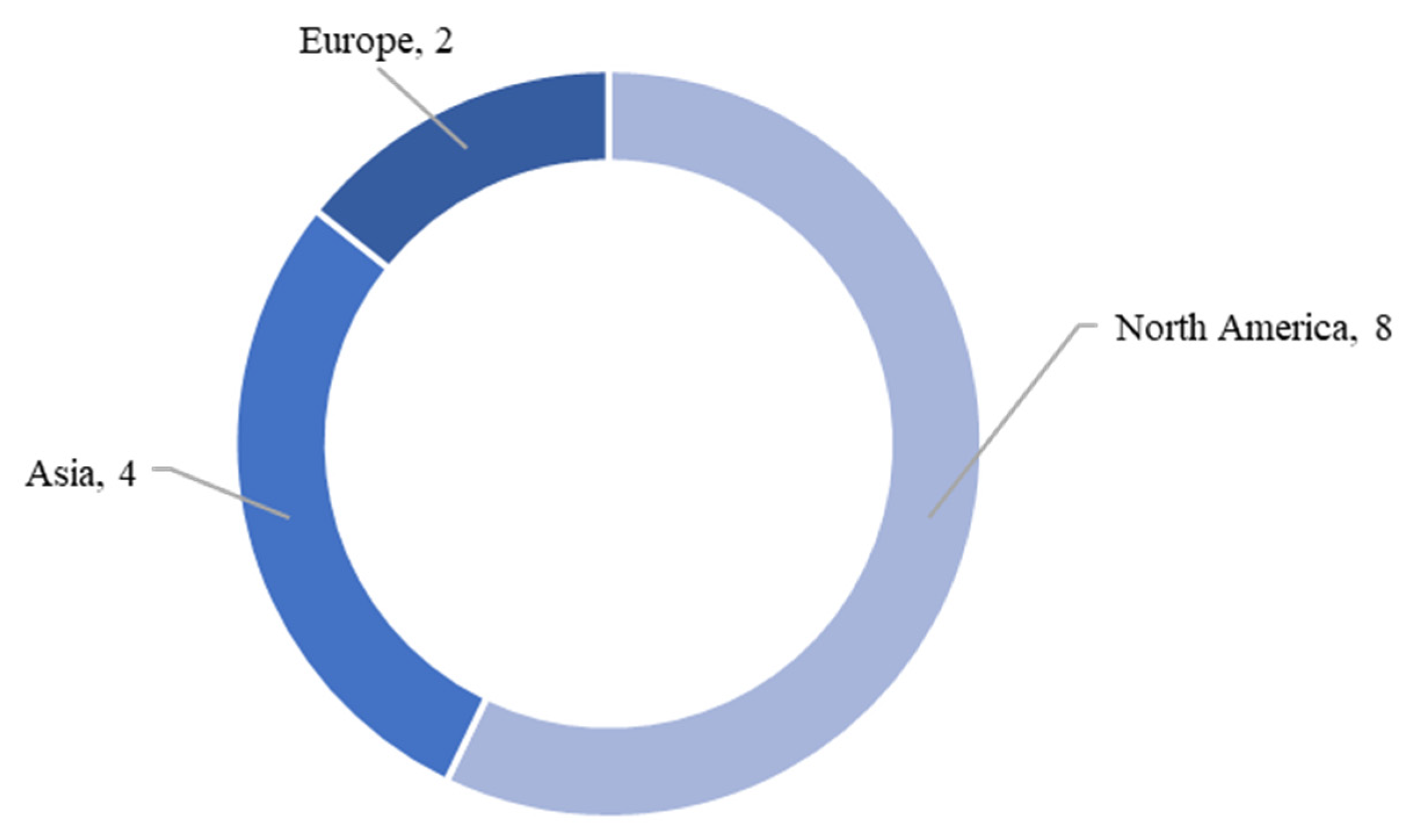

3.4. Geographical Locations

3.5. Health Strategies

3.5.1. National or State-Wide Health Strategies

3.5.2. Multi-Phase Interventions

3.5.3. Social Media Campaigns

3.5.4. Development of Physical and E-Health Communication Tools

3.6. Sources of Potential Misinformation

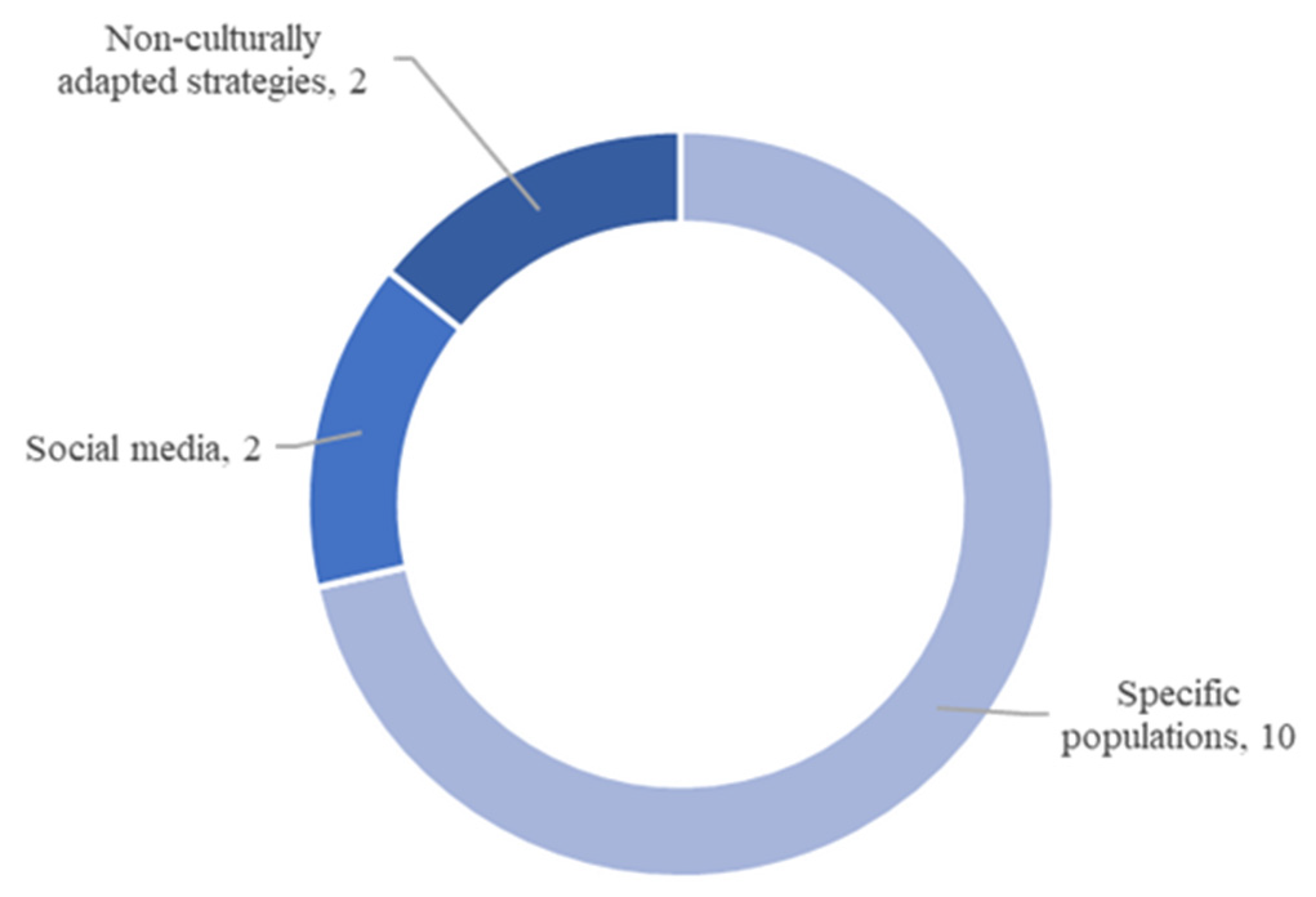

3.6.1. Information Spread Among Specific Populations

3.6.2. Social Media

3.6.3. Non-Culturally Adapted Nutritional Health Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.1.1. Mobilization of Information

4.1.2. Poor Adaptation and Implementation of Strategies

4.1.3. Poor Quality of Information

4.1.4. Importance and Effectiveness of Strategies in Addressing Potential Misinformation

4.2. Limitations and Gaps in the Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruxton, C.H.; Ruani, M.A.; Evans, C.E. Promoting and disseminating consistent and effective nutrition messages: Challenges and opportunities. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeles-Agdeppa, I.; Monville-Oro, E.; Gonsalves, J.F.; Capanzana, M.V. Integrated school based nutrition programme improved the knowledge of mother and schoolchildren. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2019, 15, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ knowledge of healthy diets and its correlation with dietary behaviour. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, D.; Wells, C. Disinformation as Political Communication. Polit. Commun. 2020, 37, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruani, M.A.; Reiss, M.J. Susceptibility to COVID-19 Nutrition Misinformation and Eating Behavior Change during Lockdowns: An International Web-Based Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lledo, V.; Alvarez-Galvez, J. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, N.; Jerin, S.I.; Mu, D. Using TikTok to Educate, Influence, or Inspire? A Content Analysis of Health-Related EduTok Videos. J. Health Commun. 2023, 28, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K.; Civen, R.; Equils, O. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Misinformation and perceptions of vaccine safety. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1950504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Seifert, C.M.; Schwarz, N.; Cook, J. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Fang, Y.; Lian, Y.; He, Y. Gluten-free diet on video platforms: Retrospective infodemiology study. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076231224594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association for Media Literacy Education. Media Literacy Defined. Available online: https://namle.org/resources/media-literacy-defined/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Kaiser, C.K.; Edwards, Z.; Austin, E.W. Media Literacy Practices to Prevent Obesity and Eating Disorders in Youth. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraak, V.I.; Story, M.; Wartella, E.A.; Ginter, J. Industry Progress to Market a Healthful Diet to American Children and Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, R.; Martin-Biggers, J.; Berhaupt-Glickstein, A.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Fruit-related terms and images on food packages and advertisements affect children’s perceptions of foods’ fruit content. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2722–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negowetti, N.; Ambwani, S.; Karr, S.; Rodgers, R.; Austin, S. Digging up the dirt on “clean” dietary labels: Public health considerations and opportunities for increased Federal oversight. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduci, E.; Vizzuso, S.; Frassinetti, A.; Mariotti, L.; Del Torto, A.; Fiore, G.; Marconi, A.; Zuccotti, G.V. Nutripedia: The Fight against the Fake News in Nutrition during Pregnancy and Early Life. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedhamzeh, S.; Nedjat, S.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Doustmohammadian, A.; Hosseini, H.; Dorosty Motlagh, A. Nutrition labels’ strengths & weaknesses and strategies for improving their use in Iran: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salka, B.; Aljamal, M.; Almsaddi, F.; Kaakarli, H.; Nesi, L.; Lim, K. TikTok as an Educational Tool for Kidney Stone Prevention. Cureus 2023, 15, e48789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Hershey, M.S.; Zazpe, I.; Trichopoulou, A. Transferability of the Mediterranean diet to non-Mediterranean countries. What is and what is not the Mediterranean diet. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvecchio Arenas, A.; González, W.; Théodore, F.L.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Alvarado, R.; Fernández-Gaxiola, A.C.; Rawlinson, C.J.; de la Vega, A.V.; Neufeld, L.M. Translating Evidence-Based Program Recommendations into Action: The Design, Testing, and Scaling up of the Behavior Change Strategy EsIAN in Mexico. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 2310S–2322S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.O.; Power, T.G.; Beck, A.D.; Betz, D.; Goodell, L.S.; Hopwood, V.; Jaramillo, J.A.; Lanigan, J.; Martinez, A.D.; Micheli, N.; et al. Twelve-Month Efficacy of an Obesity Prevention Program Targeting Hispanic Families With Preschoolers From Low-Income Backgrounds. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, T.; McGloin, A.F.; Faughnan, M.; Foley-Nolan, C.; Dwyer, V. “Babies know the facts about folic”: A behavioural change campaign utilising digital and social media. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, E253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.R.; Moore, C.; Parks, L.; Taveras, E.M.; Wiehe, S.E.; Carroll, A.E. Human-centered designed communication tools for obesity prevention in early life. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 35, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, N.M.; Kay, M.C. Perspectives on healthy eating practices and acceptance of WIC-approved foods among parents of young children enrolled in WIC. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, W.; Bailey, W.; Braun, P.; Weiss, K.; Heichelbech, J. Busting the Baby Teeth Myth and Increasing Children’s Consumption of Tap Water: Building Public Will for Children’s Oral Health in Colorado. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oli, N.; Vaidya, A.; Eiben, G.; Krettek, A. Effectiveness of health promotion regarding diet and physical activity among Nepalese mothers and their young children: The Heart-health Associated Research, Dissemination, and Intervention in the Community (HARDIC) trial. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1670033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Olickal, J.J. Effectiveness of nutrition education in improving fruit and vegetable consumption among selected college students in urban Puducherry, South India. A pre-post intervention study. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020, 34, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, M.K.; Nigg, C.R.; Fialkowski, M.K.; Braun, K.L.; Li, F.; Novotny, R. Influence of Teachers’ Personal Health Behaviors on Operationalizing Obesity Prevention Policy in Head Start Preschools: A Project of the Children’s Healthy Living Program (CHL). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Pei, Y. Linking social media overload to health misinformation dissemination: An investigation of the underlying mechanisms. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2022, 8, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Associated Terms | Exclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Misinformation | Disinformation; misinformation; misconceptions; lack of health literacy; unawareness; being uninformed | – |

| Health prevention strategies | Active promotion; defined and named campaign/intervention/strategy; social media hashtag campaigns that aimed to tackle misconceptions | Excluding campaigns that are management, not prevention; excluding guidelines—not active promotion; food labeling that was not prevention or that was discussed generally, e.g., on a national level |

| Nutrition | Supplements, probiotics, mineral intake, breastfeeding, nutrients, diet, calories | – |

| Title, Date, Country/Region | Author | Study Aim | Study Design | Population and Sample Size | Intervention | Source of Potential Misinformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutripedia: The Fight against the Fake News in Nutrition during Pregnancy and Early Life, 2021, Italy (Online) | Verduci et al. [19] | Introduced novel tools of e-health communication with the scope of counteracting nutritional fake news concerning pregnancy | Interventional study using e-health communication tools (both qualitative and quantitative) | Parents Website engagement: 220,000 total views Social Media Reach: 9 million Chatbot: 14,698 downloads | Promoted new e-health communication tools, i.e., Nutripedia website and Chatbot app via non-governmental organization outreach, digital media sources, and scientific society conferences. Delivered general population advice, as well as individualized information and intervention. Information focused on nutritional knowledge (preconception, pregnancy, children up to 3 years). | Fake news concerning pregnancy and first 1000 days of life. Lack of support for new parents and obstacles in nutritional knowledge could leave them susceptible to inaccurate online information. Parents’ nutritional knowledge was affected by online tools, social environment, peers’ advice, medical assistance, and personal convictions. |

| Nutrition labels’ strengths & weaknesses and strategies for improving their use in Iran: A qualitative study, 2020, Iran | Seyedhamzeh et al. [20] | Explained the strengths and weaknesses of the traffic light label, and nutrition fact label and the strategies for improving their use in Iran | Qualitative Study—Focus Group Discussions | Mothers, n = 63; food quality control expert (FQC), n = 10; nutritionists, n = 6; and food industry experts, n = 8 | Traffic light label (TLL) and nutrition facts label (NFL) | Mothers: Lack of trust in information provided by the manufacturers, incompatibility with the culture Otherwise, labels misleading the consumer, discrepancies in coloring reported by different laboratories, different approaches adopted by regulatory experts, ambiguity, and lack of supervision and consistency. |

| TikTok as an Educational Tool for Kidney Stone Prevention, 2023, USA | Salka et al. [21] | Evaluated the reach and quality of kidney stone prevention information on TikTok | Cross-sectional analysis | TikTok users Videos, English, related to hashtag/topic, with >1000 views, 87 videos, 8.75 million views | TikTok campaign #kidneystoneprevention | The majority of the TikTok videos, which did not meet American Urological Association recommendations for diet therapies in stone prevention. |

| Transferability of the Mediterranean diet to non-Mediterranean countries. What is and what is not the Mediterranean diet, 2017, USA | Martínez-González et al. [22] | Presented strategies necessary for promoting MedDiet to non-Med context, i.e., Americans | Cumulative meta-analysis | Those at risk for cardiovascular disease, 27 articles | Mediterranean Diet | Popular definitions of MedDiet were not in line with traditional diet, leading to myths/misconceptions and the promotion of foods that are not in line with MedDiet benefits. |

| Translating Evidence-Based Program Recommendations into Action: The Design, Testing, and Scaling Up of the Behavior Change Strategy EsIAN in Mexico, 2019, Mexico | Bonvecchio Arenas et al. [23] | Described the process and evidence-based approach used to design and rollout the EsIAN at scale. Focused on the behavior change communication component. | Mixed methods | Mothers/caregivers of children aged < 5 years, healthcare providers, experts, up to n = 1387, depending on the phase of the study | Integrated strategy for attention to nutrition, specifically the implementation of the behavior change communication (BCC) strategy component | Mothers: Misconceptions during pregnancy and breastfeeding, e.g., ‘they should eat for two during pregnancy’. Cultural beliefs could stem from mothers, mothers-in-law, fathers, and grandparents. Primary healthcare providers also sometimes lacked the knowledge concerning nutrition advice during pregnancy and lactation. Recommendations did not always align with global and national guidelines for mothers/caregivers. |

| Twelve-Month Efficacy of an Obesity Prevention Program Targeting Hispanic Families With Preschoolers From Low-Income Backgrounds, 2021, USA | Hughes et al. [24] | Assessed effects of an obesity prevention program which promoted eating self-regulation and healthy preferences | Randomized control trial | Hispanic preschool children (parents + families with low incomes) Families recruited from Head Start across 2 sites, 255 families randomized (prevention n = 136; control n = 119) | SEEDS (Strategies for Effective Eating Development) obesity prevention program. Curriculum aiming to change feeding knowledge/practices/styles (parent); BMI percentile, eating self-regulation, trying new foods, and fruit/vegetable consumption (child). | Mothers were sometimes a source of feeding misconceptions. |

| “Babies know the facts about folic”: A behavioral change campaign utilizing digital and social media, 2016, Ireland (Hybrid) | Flaherty et al. [25] | Assessed if the “Babies Know the Facts about Folic” campaign changed women’s knowledge, attitudes and behavior towards folic acid supplements | Online survey was conducted pre- and post-campaign. Home face-to-face interviews were conducted three months after the campaign. | Women of a childbearing age who were sexually active and could become pregnant online survey: n = 656/738, interviews: n = 424 | “Safefood” launched a social and digital media campaign in 2015. | Misconceptions of women concerning the supplementation of folic acid prior to and during pregnancy could lead to low consumption of the supplement despite benefits. |

| Human-centered designed communication tools for obesity prevention in early life, 2023, USA (Indianapolis) | Cheng et al. [26] | Developed tools to ease the provider–parent communication about obesity prevention in a pediatric setting | Co-designed workshops with parents and pediatricians | Parents and caregivers of children aged 0–24 months, n = 13; and pediatricians, n = 13 | Activities based on a human-centered design, involving parents and pediatricians. Activity 1: Discussion of communication barriers/facilitators in child obesity prevention. Activity 2: Creation of visual aids to facilitate the parent–provider communication. | There were knowledge barriers and misconceptions relating to infant feeding. In a needs assessment of parents of children aged 0–24 months, only a few parents viewed obesity in early life as a health issue. |

| Perspectives on healthy eating practices and acceptance of WIC-approved foods among parents of young children enrolled in WIC, 2023, USA | Hammad and Kay [27] | Analyzed what parents consider healthy food habits, their acceptance of certain food categories, and the acknowledgement of digital tools to improve diet quality | Qualitative interviews | Parents or caregivers of children aged 0–2 years who received benefits from the “Special Supplement Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children”, had a cell phone, and spoke English, n = 13 | The “Special Supplement Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children” aimed to improve nutritional intake of low-income mothers and their 0–5-year-old children. Food packages containing vouchers for nutrient-rich foods were distributed to the intervention’s beneficiaries. However, the program has lately faced a decrease in participation, retention, and the redemption of food packages. | Mothers had different definitions of healthy versus unhealthy eating, possibly due to the variety of sources consulted to find nutrition information, e.g., social media, Google, YouTube, nutritionist from the intervention, friends, family, partners, cooking shows, research, and own common sense. |

| Busting the Baby Teeth Myth and Increasing Children’s Consumption of Tap Water: Building Public Will for Children’s Oral Health in Colorado, 2017, USA | Hornsby et al. [28] | Evaluated if a communication campaign could change behavior to limit children’s fruit juice consumption and increase tap water consumption to improve oral health | Pre- and post-campaign surveys applying quantitative methods | Low-income families living in Colorado who had a child between 6 months and 6 years of age, n = 603 (2014)/600 (2015) | “Cavities Get Around” is a statewide communication campaign including television and radio advertisements, social media, health promoters, educational programs, text messaging, and community partnerships to increase children’s consumption of tap water and decrease consumption of fruit juice and other sugary drinks. | Fruit juice was commonly regarded as healthy, although it contains a lot of sugar and therefore increases the risk for tooth decay in infants and children. Moreover, many parents underestimated the importance of baby teeth, regarding them as less important than adult teeth. Many parents did not know that cavities could spread from baby to adult teeth. |

| Effectiveness of health promotion regarding diet and physical activity among Nepalese mothers and their young children: The Heart-health Associated Research, Dissemination, and Intervention in the Community, 2019, Nepal (HARDIC) trial | Oli et al. [29] | Assessed the effectiveness of a health promotion intervention on mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and their children’s behavior regarding diet and physical activity | Baseline and follow-up survey (quantitative methods) | Mothers of children aged 1–9 living in one of the two neighboring villages of Duwakot (intervention area) or Jhaukhel (control area), n = 323 mothers completed round 1 of the intervention n = 105 mothers completed round 2 of the intervention | The “Heart-health Associated Research, Dissemination, and Intervention in the Community”, (HARDIC) is a community-based health education program designed to improve diet and physical activity as part of cardiovascular health promotion. A total of 47 peer mothers were trained to conduct five education classes for about 10 mothers each. | There were widespread misconceptions by mothers who did not always understand the composition of healthy food. |

| Effectiveness of nutrition education in improving fruit and vegetable consumption among selected college students in urban Puducherry, South India. A pre-post intervention study, 2020, India (Puducherry) | Patel et al. [30] | Evaluated the effectiveness of nutrition education in improving the daily intake of fruit and vegetable servings and stage of behavior change among college students | Randomized control trial | Urban college students, n = 150 | Intervention Group: 30 min nutrition education program Control Group: Pamphlets regarding healthy dietary intake | Initially, there was less knowledge regarding portion sizes, and average daily servings of fruit and vegetable intake among college students. |

| Gluten-free diet on video platforms: Retrospective infodemiology study, 2024, China | Ye et al. [11] | Examined the trends, content, and quality of information on two social media platforms | Mixed Methods: Mann–Kendall tests, DISCERN, HONcode | Videos using #GFD on TikTok and BiliBili, TikTok, n = 49 BiliBili, n = 86 | Gluten-free diet videos | The quality of health information videos on Chinese video platforms were poor. The majority of them were not rigorous enough, containing misleading messaging that could promote unproven treatments with no discussion of possible side effects. |

| Influence of Teachers’ Personal Health Behaviors on Operationalizing Obesity Prevention Policy in Head Start Preschools: A Project of the Children’s Healthy Living Program (CHL), 2016, Hawaii | Esquivel et al. [31] | Quantified the Head Start (HS) teacher mediating and moderating influence on the effect of a wellness policy intervention | Intervention trial within a larger randomized community trial | Teachers from 23 Head Start (HS) classrooms, n = 46 | Seven-month multi-component intervention with policy changes to food served and service style, initiatives for employee wellness, classroom activities for preschoolers promoting physical activity (PA) and healthy eating, and training and technical assistance | Knowledge, beliefs, priorities, and misconceptions around child nutrition among teachers could influence child nutrition and obesity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero, A.; Chapi-Nitcheu, C.; Vallan, L.; Flahault, A.; Hasselgard-Rowe, J. Relationships Between Misinformation Variables and Nutritional Health Strategies: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060891

Caballero A, Chapi-Nitcheu C, Vallan L, Flahault A, Hasselgard-Rowe J. Relationships Between Misinformation Variables and Nutritional Health Strategies: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060891

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero, Andrea, Cassandra Chapi-Nitcheu, Laura Vallan, Antoine Flahault, and Jennifer Hasselgard-Rowe. 2025. "Relationships Between Misinformation Variables and Nutritional Health Strategies: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060891

APA StyleCaballero, A., Chapi-Nitcheu, C., Vallan, L., Flahault, A., & Hasselgard-Rowe, J. (2025). Relationships Between Misinformation Variables and Nutritional Health Strategies: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060891