Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall EU Population

3.2. Proportionate Mortality

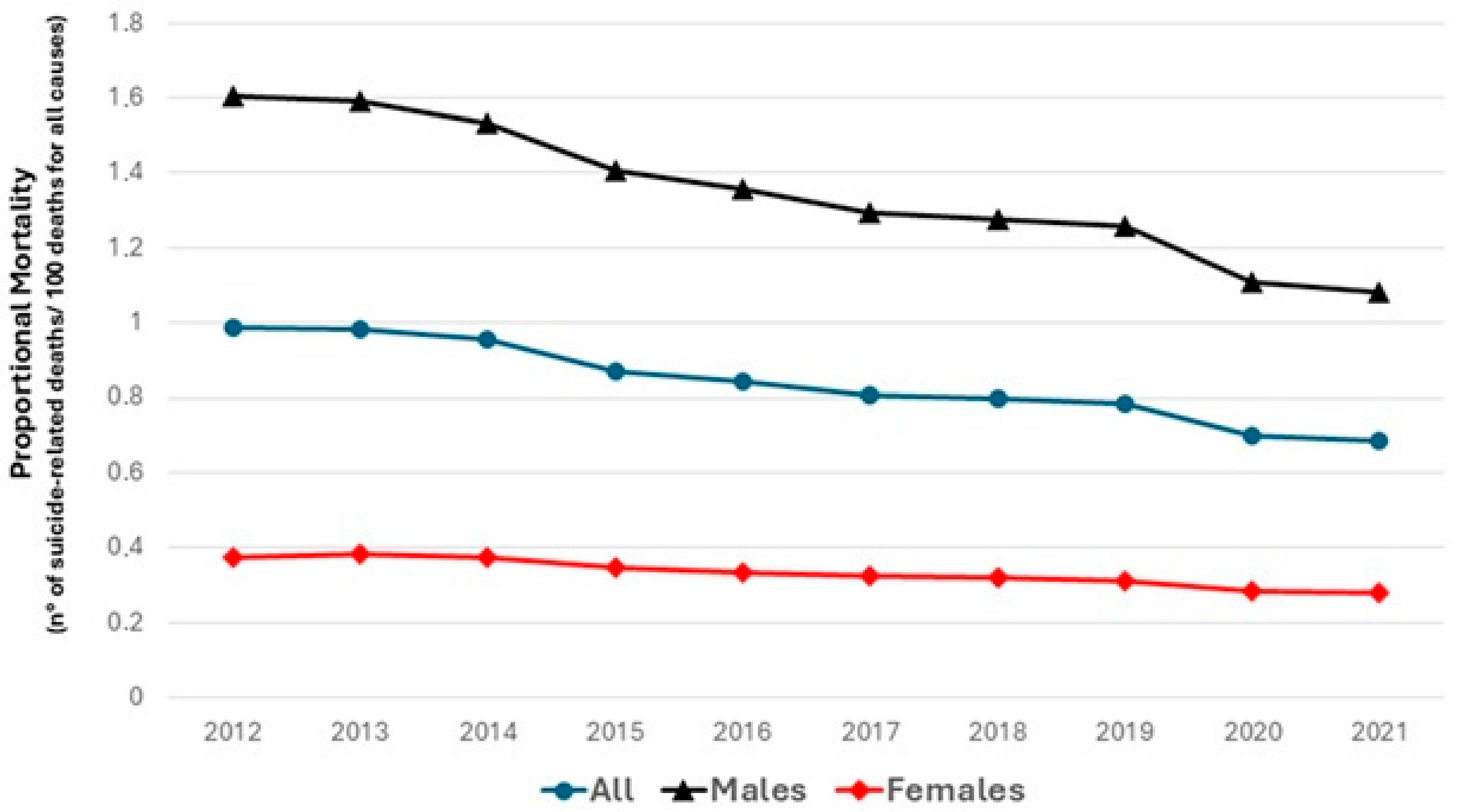

3.3. Sex

3.4. Age

3.5. Trends in Suicide-Related Mortality by European Sub-Regions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henry, M. Suicide prevention: A multisectorial public health concern. Prev. Med. 2021, 152, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, D.; Giannotti, A.V. Suicide in late life: A viewpoint. Prev. Med. 2021, 152, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arensman, E.; Scott, V.; De Leo, D.; Pirkis, J. Suicide and Suicide Prevention from a Global Perspective. Crisis 2020, 41, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 9789241564779. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. LIVE LIFE: An Implementation Guide for Suicide Prevention in Countries; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 9789240026629. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/demo_mor_esms.htm (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Naghavi, M. Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019, 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-manuals-and-guidelines/-/ks-ra-13-028 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Kim, H.; Fay, M.; Yu, B.; Barrett, M.; Feuewr, E. Comparability of segmented line regression models. Biometrics 2004, 60, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.A.; Kaplan, M.S.; Stone, D.M.; Zhou, H.; Stevens, M.R.; Simon, T.R. Suicide Among Males Across the Lifespan: An Analysis of Differences by Known Mental Health Status. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 63, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; Feigelman, W.; Rosen, Z. Association of high traditional masculinity and risk of suicide death: Secondary analysis of the add health study. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretta, R.F.; McKee, S.A.; Rhee, T.G. Gender differences in risks of suicide and suicidal behaviors in the USA: A narrative review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D. Late-life suicide in an aging world. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, S.; Erlangsen, A.; Waern, M.; De Leo, D.; Oyama, H.; Scocco, P.; Gallo, J.; Szanto, K.; Conwell, Y.; Draper, B.; et al. A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis 2011, 32, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D.; Draper, B.M.; Snowdon, J.; Kõlves, K. Suicides in older adults: A case-control psychological autopsy study in Australia. J. Psychiatr Res. 2013, 47, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, D. Ageism and suicide prevention. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 192–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, M.; Haro, J.M.; Bernert, S.; Brugha, T.; de Graaf, R.; Bruffaerts, R.; Lépine, J.P.; de Girolamo, G.; Vilagut, G.; Gasquet, I.; et al. Risk factors for suicidality in Europe: Results from the ESEMED study. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 101, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Suicide Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e189–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das-Munshi, J.; Thornicroft, G. Failure to tackle suicide inequalities across Europe. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Resurrección, D.M.; Antunes, A.; Frasquilho, D.; Cardoso, G. Impact of economic crises on mental health care: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 29, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, P.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Roberts, H.; Helbich, M. Is suicide mortality associated with neighbourhood social fragmentation and deprivation? A Dutch register-based case-control study using individualised neighbourhoods. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2020, 74, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, L.; Wagner, B. Efficacy of an online gatekeeper program for relatives of men at risk of suicide—A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.E.; Stewart, C.C.; Gary, M.C.; Richards, J.E. Detecting and Assessing Suicide Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2021, 47, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, C.; Wakefield, J.R.H. Financial distress and suicidal behaviour during COVID-19: Family identification attenuates the negative relationship between COVID-related financial distress and mental Ill-health. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, N.; Mudhar, M.; Munksgaard, F.S. ‘Let communities do their work’: The role of mutual aid and self-help groups in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Disasters 2021, 45 (Suppl. S1), S146–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegerl, U.; Wittenburg, L.; Arensman, E.; Van Audenhove, C.; Coyne, J.C.; McDaid, D.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Gusmão, R.; Kopp, M.; Maxwell, M.; et al. Optimizing suicide prevention programs and their implementation in Europe (OSPI Europe): An evidence-based multi-level approach. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Patton, G.; Berk, M.; Patel, V. Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in low-income and middle-income countries: Systematic review and theory of change. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1729–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Er, S.T.; Demir, E.; Sari, E. Suicide and economic uncertainty: New findings in a global setting. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 22, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalsman, G.; Hawton, K.; Wasserman, D.; van Heeringen, K.; Arensman, E.; Sarchiapone, M.; Carli, V.; Höschl, C.; Barzilay, R.; Balazs, J.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Apter, A.; Bertolote, J.; Beautrais, A.; Currier, D.; Haas, A.; Hegerl, U.; Lonnqvist, J.; Malone, K.; Marusic, A.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA 2005, 294, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Williams, D.J.; Feinstein, J.A.; Grijalva, C.G.; Zhu, Y.; Dickinson, E.; Stassun, J.C.; Sekmen, M.; Tanguturi, Y.C.; Gay, J.C.; et al. Positive predictive value of ICD-10 Codes to identify acute suicidal and self harm behaviors. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, e207–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabella, B.A.; Hume, B.; Li, L.; Mabida, M.; Costich, J. Multi-site medical record review for validation of intentional self-harm coding in emergency departments. Inj. Epidemiol. 2022, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.S.; Taylor, L.G.; Braver, E.R.; Liu, W.; Pinheiro, S.P.; Mosholder, A.D. A systematic review of validated suicide outcome classification in observational studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J.B.; Martin, C.E.; Pearson, J.L. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockett, I.R.; Lian, Y.; Stack, S.; Ducatman, A.M.; Wang, S. Discrepant comorbidity between minority and white suicides: A national multiple cause-of-death analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate (per 100,000) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | AAPC | 95% CI | p | Joinpoints | APC Period 1 (Years); APC (95% CI); p | APC Period 2 (Years); APC (95% CI); p | |

| Europe | 12.3 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.2 | −2.2 | −2.7 to −1.8 | <0.001 | 0 | - | - |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Europe Men | 20.7 | 20.6 | 20.2 | 19.5 | 18.7 | 17.7 | 17.2 | 16.8 | 16.7 | 16.6 | −2.4 | −2.9 to −2.0 | <0.001 | 1 | [2012–2017] −3.4 (−5.4 to −2.7) p < 0.001 | [2017–2021] −1.0 (−2.3 to 1.7) p = 0.33 |

| Europe Women | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | −1.9 | −2.7 to −1.0 | <0.001 | 0 | - | - |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| <65 years | 10.8 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 9 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.6 | −2.7 | −3.0 to −2.3 | <0.001 | 0 | - | - |

| ≥65 years | 18.8 | 18.7 | 18.2 | 17.9 | 17.0 | 16.6 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 16.5 | 16.8 | −1.3 | −1.9 to −0.9 | <0.001 | 1 | [2012–2019] −2.2 (−3.8 to −1.7) p = 0.003 | [2019–2021] 1.9 (−1.2 to 3.7) p = 0.30 |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality Rate (per 100,000) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | AAPC | 95% CI | p | Joinpoints | APC Period 1 (Years); APC (95% CI); p | APC Period 2 (Years); APC (95% CI); p | P for Parallelism | |

| All | North vs West p = 0.06 North vs West p = 0.004 North vs South p = 0.003 West vs East p = 0.01 West vs South p = 0.55 East vs South p = 0.04 | ||||||||||||||||

| North | 12.6 | 14.4 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.3 | 11.8 | −0.8 | −1.7 to 0.1 | 0.06 | 0 | - | - | |

| West | 15.5 | 15.1 | 15.0 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 11.4 | −2.6 | −3.6 to −1.6 | <0.001 | 0 | - | - | |

| East | 18.3 | 18.1 | 17.3 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 14.0 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 12.3 | −3.8 | −4.7 to −3.0 | <0.001 | 1 | (2012–2013) 0.1 (−3.9 to 4.6) p = 0.72 | (2013–2021) −4.7 (−8.0 to −4.0) p < 0.001 | |

| South | 9.6 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.9 | −2.0 | −3.7 to −0.3 | 0.02 | 0 | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuin, M.; de Leo, D. Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060890

Zuin M, de Leo D. Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060890

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuin, Marco, and Diego de Leo. 2025. "Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060890

APA StyleZuin, M., & de Leo, D. (2025). Suicide-Related Mortality Trends in Europe, 2012–2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060890