Culturally Adapted, Clinician-Led, Bilingual Group Exercise Program for Older Migrant Adults: Single-Arm Pre–Post-Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Program Adaptation Framework

2.2. Intervention Description

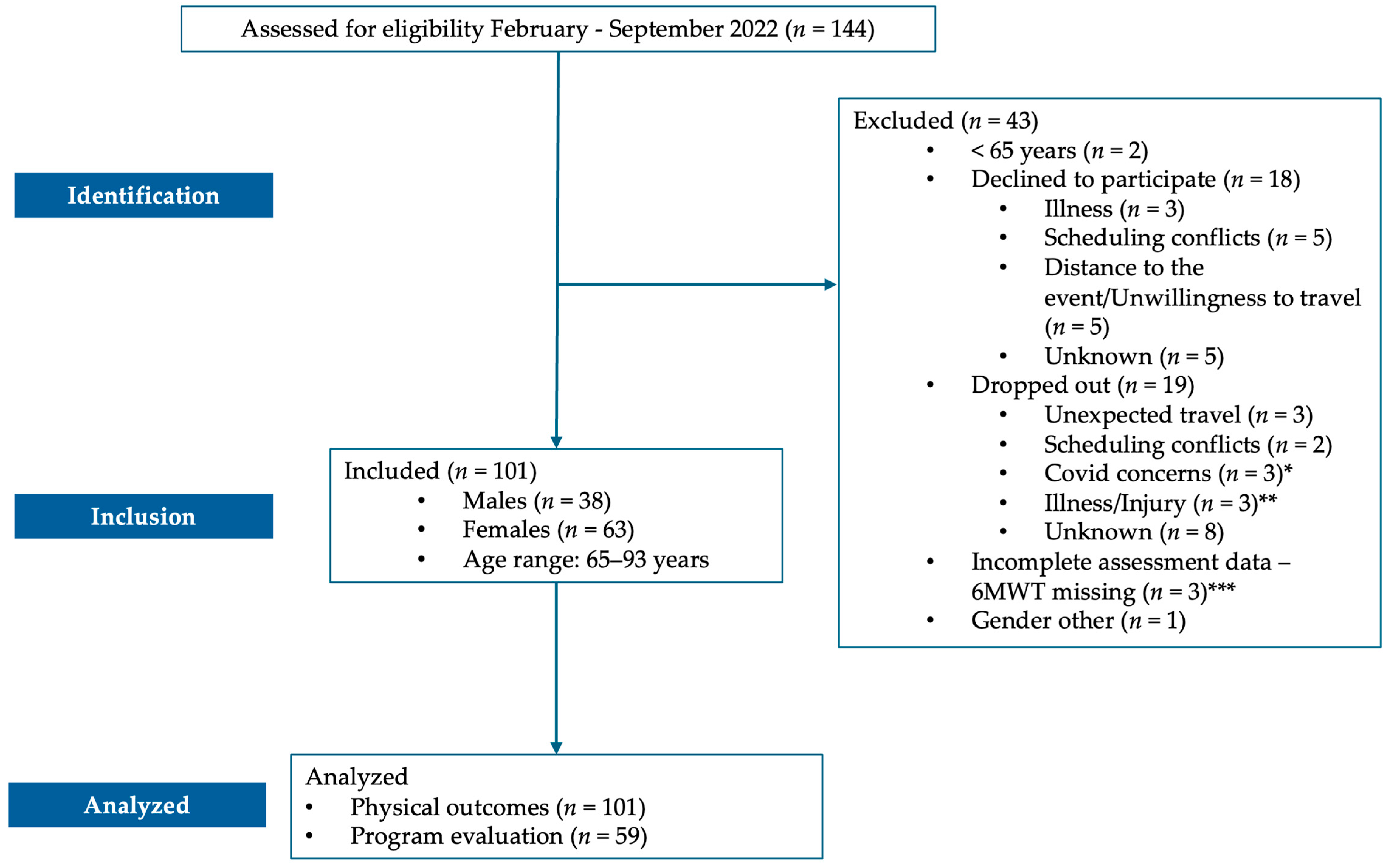

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Measures and Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Move Together MADI Results

3.2. Move Together Participants’ Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australia’s Population by Country of Birth. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. People and Communities. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Olofsson, J.; Rämgård, M.; Sjögren-Forss, K.; Bramhagen, A.-C. Older migrants’ experience of existential loneliness. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Dowsey, M.M.; Woodward-Kron, R.; O’Brien, P.; Hawke, L.; Bunzli, S. Physical activity amongst culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia: A scoping review. Ethn. Health 2023, 28, 1195–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhammer, B.; Bergland, A.; Rydwik, E. The Importance of Physical Activity Exercise Among Older People. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7856823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Das, P.; Horton, R. Physical activity—Time to take it seriously and regularly. Lancet 2016, 388, 1254–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.; Fairhall, N.J.; Wallbank, G.K.; Tiedemann, A.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Howard, K.; Clemson, L.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD012424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Ju, Y.; Min, S.-K.; Cho, J.; Kim, H.; Ha, Y.-C.; Rhee, Y.; Kim, Y.-P.; et al. Position Statement: Exercise Guidelines for Osteoporosis Management and Fall Prevention in Osteoporosis Patients. J. Bone Metab. 2023, 30, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, J.; Montiel-Rojas, D.; Nilsson, A.; Kadi, F. Engagement in Muscle-Strengthening Activities Lowers Sarcopenia Risk in Older Adults Already Adhering to the Aerobic Physical Activity Guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Wang, P. Optimal exercise dose and type for improving sleep quality: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1466277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescatello, L.S.; MacDonald, H.V.; Lamberti, L.; Johnson, B.T. Exercise for Hypertension: A Prescription Update Integrating Existing Recommendations with Emerging Research. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, G.A.; Taylor, B.A.; MacDonald, H.V.; Johnson, B.T.; Zaleski, A.L.; Livingston, J.; Thompson, P.D.; Pescatello, L.S. Can Exercise Improve Cognitive Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahor, M.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Blair, S.; Bonds, D.E.; Church, T.S.; Espeland, M.A.; Fielding, R.A.; Gill, T.M.; Groessl, E.J.; et al. Effect of Structured Physical Activity on Prevention of Major Mobility Disability in Older Adults: The LIFE Study Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, S.; Nunan, D.; Dixon, A.; Maruthappu, M.; Butler, K.; Gray, M. Focus on physical activity can help avoid unnecessary social care. BMJ 2017, 359, j4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasenius, N.S.; Isomaa, B.A.; Östman, B.; Söderström, J.; Forsén, B.; Lahti, K.; Hakaste, L.; Eriksson, J.G.; Groop, L.; Hansson, O.; et al. Low-cost exercise interventions improve long-term cardiometabolic health independently of a family history of type 2 diabetes: A randomized parallel group trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020, 8, e001377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijneveld, S.A. Promotion of health and physical activity improves the mental health of elderly immigrants: Results of a group randomised controlled trial among Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands aged 45 and over. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, G.; Robertson, C.; Hartmann, T.; Rossiter, R. Effectiveness and Benefits of Exercise on Older People Living with Mental Illness’ Physical and Psychological Outcomes in Regional Australia: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 31, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, B.; Rosenwax, L.; Lee, E.A.; Same, A. Evaluation of a healthy ageing intervention for frail older people living in the community. Australas. J. Ageing 2016, 35, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, T.; Flaxman, S.; Guthold, R.; Semenova, E.; Cowan, M.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C.; Stevens, G.A.; Country Data Author Group. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1232–e1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.; Kendall, E.; See, L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: A systematic literature review: The effectiveness to manage or prevent chronic disease in CALD communities. Health Soc. Care Community 2011, 19, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, J.; Sevoyan, M.; Pate, R.R. Acculturation and leisure-time physical activity among Asian American adults in the United States. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 1900–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.B.; Assefa, Y. Access to health services among culturally and linguistically diverse populations in the Australian universal health care system: Issues and challenges. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.; Kendall, E. Culturally and linguistically diverse peoples’ knowledge of accessibility and utilisation of health services: Exploring the need for improvement in health service delivery. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2011, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, E.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Wan, C.S.; Goh, A.M.Y.; Curran, E.; Chong, T.W.H.; Anstey, K.J.; Hanna, F.; Ellis, K.A. Ethnic Differences in Barriers and Enablers to Physical Activity Among Older Adults. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 691851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caperchione, C.M.; Kolt, G.S.; Mummery, W.K. Examining Physical Activity Service Provision to Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Communities in Australia: A Qualitative Evaluation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Tong, C.; Macdonald, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Adapting an Effective Health-Promoting Intervention-Choose to Move-for Chinese Older Adults in Canada. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2024, 32, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, S.; Shah, S.; Patel, M.; Tamim, H. Effectiveness of a Tai Chi Intervention for Improving Functional Fitness and General Health Among Ethnically Diverse Older Adults with Self-Reported Arthritis Living in Low-Income Neighborhoods: A Cohort Study. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 38, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, M.; Chiu, C.L.; Laing, T.; Chowdhury, N.; Gwynne, K. A Web-Delivered, Clinician-Led Group Exercise Intervention for Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Single-Arm Pre-Post Intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, M.; Chiu, C.L.; Hay, M.; Laing, T. Community-Based Exercise and Lifestyle Program Improves Health Outcomes in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, M.; Gwynne, K.; Laing, T.; Hay, M.; Chowdhury, N.; Chiu, C.L. Can Health Improvements from a Community-Based Exercise and Lifestyle Program for Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Be Maintained? A Follow up Study. Diabetology 2022, 3, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; DiPierro, M.; Chen, L.; Chin, R.; Fava, M.; Yeung, A. The evaluation of a culturally appropriate, community-based lifestyle intervention program for elderly Chinese immigrants with chronic diseases: A pilot study. J. Public Health 2014, 36, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Masri, A.; Kolt, G.S.; George, E.S. Physical activity interventions among culturally and linguistically diverse populations: A systematic review. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Nathan, A.; Choi, W.K.; Ngan, W.; Yin, S.; Thornton, L.; Barnett, A. Built and social environmental factors influencing healthy behaviours in older Chinese immigrants to Australia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montayre, J.; Neville, S.; Dunn, I.; Shrestha-Ranjit, J.; Clair, V.W. What makes community-based physical activity programs for culturally and linguistically diverse older adults effective? A systematic review. Australas. J. Ageing 2020, 39, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnicow, K.; Baranowski, T.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Braithwaite, R.L. Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethn. Dis. 1999, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yancey, A.K.; Ory, M.G.; Davis, S.M. Dissemination of Physical Activity Promotion Interventions in Underserved Populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.A.; Moore, J.E.; Wiltsey Stirman, S.; Birken, S.A. Towards a comprehensive model for understanding adaptations’ impact: The model for adaptation design and impact (MADI). Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed.; Liguori, G., Feito, Y., Fountaine, C.J., Roy, B., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-1-9751-5018-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Development and Validation of Criterion-Referenced Clinically Relevant Fitness Standards for Maintaining Physical Independence in Later Years. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chung, P.-K.; Wang, S. Functional fitness norms and trends of community-dwelling older adults in urban China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Neubeck, L.; Gullick, J.; Koo, F.; Ding, D. Marked differences in cardiovascular risk profiles in middle-aged and older Chinese residents: Evidence from a large Australian cohort. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Guo, Q.Q.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, Z.X.; Li, Y.Y. The Evolutionary Stage of Cognitive Frailty and Its Changing Characteristics in Old Adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtin, E.; Knapp, M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.D.; Tu, Q.; Bickford, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. The Experiences of Older Chinese Migrants with Chronic Diseases During COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 8264936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Kennedy, M.; Salma, J. A Scoping Review on Community-Based Programs to Promote Physical Activity in Older Immigrants. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2023, 31, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, J.M.; Wagnild, J.M.; Pollard, T.M.; Roberts, T.R.; Ahkter, N. Effectiveness of diet and physical activity interventions among Chinese-origin populations living in high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Piliae, R.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Waters, C.M.; Froelicher, E.S. Change in perceived psychosocial status following a 12-week Tai Chi exercise programme. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 54, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagroep, W.; Cramm, J.M.; Denktaș, S.; Nieboer, A.P. Behaviour change interventions to promote health and well-being among older migrants: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Chen, D.; Swartz, M.C.; Sun, H. A Pilot Study of a Culturally Tailored Lifestyle Intervention for Chinese American Cancer Survivors. Cancer Control 2019, 26, 1073274819895489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.-C.; Heo, M.; Suchday, S.; Wong, A.; Poon, E.; Liu, G.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program for diabetes risk reduction in Chinese immigrants in New York City. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titler, M. Translation Research in Practice: An Introduction. OJIN Online J. Issues Nurs. 2018, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adaptation Areas | Mediating/Moderating Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Program | Beat It (In Person) | Move Together |

| Facilitator training | 12 h of online learning; 1-day in-person practical training | Additional 2 h of online training covering social isolation and inclusion, Move Together program logistics, facilitator requirements, and key considerations |

| Marketing | Direct mail (via post), email, and website (English only) | Digital—email and website, print marketing (English and simplified Chinese), radio advertising, and community outreach via new and established links with community leaders and Chinese community groups |

| Participant resources | Beat It participant handbook Home exercise resource Theraband | All participant-facing resources are culturally adapted and translated by Mandarin-speaking health professional staff of Chinese background and translated into simplified Chinese (written Mandarin script) through an external translation company with community review of translated materials included to ensure accuracy and cultural appropriateness Move Together participant handbook Education session topics altered to suit general population attendees rather than diabetes-specific information Removal of diabetes-specific content e.g., blood glucose level logs Simplified-Chinese-translated Guide to Healthy Eating brochure Theraband |

| Trainer resources | Beat It in-person delivery manual Beat It facilitator manual (education sessions) | Move Together delivery manual adapted from Beat It Additional information on the purpose of the program and ways to promote social inclusion Adjustment to program inclusion criteria to suit > 65-year-old Mandarin-speaking participants Changes to program timeline and requirements Adapted Move Together facilitator manual Changes to content to reflect educational topics Inclusion of language-specific and culturally adapted resources to use during education and exercise sessions |

| Medical clearance | Standardized medical clearance form, including recommended program inclusion/exclusion criteria, medical history, medications, and latest HbA1c and lipid test results Participants typically bring a physical copy of a medical clearance form to the initial consultation with the Beat It trainer | Additional considerations and exclusion criteria for determining suitability to join the Move Together program including 65 years or older (requirement of funding to tailor the program for people over 65 years of age); Mandarin-speaking person |

| Pre-program | Pre-program resources sent including a welcome letter confirming program registration, medical clearance, and initial consultation process Beat It trainer books initial assessment appointment | Participant materials sent translated into simplified Chinese Confirmation letter Medical clearance Schedule template Move Together trainer books initial assessment |

| Initial and final assessment | Conducted in person Obtain medical clearance, participant informed consent, and emergency contact information and complete pre-screening questionnaire Complete baseline measurements, including height, weight, waist circumference, BP, and HR Complete exercise tests, including 6-min walk test (6MWT), 30-s sit-to-stand, 30-s seated arm curl test, seated sit and reach, and single-leg stance test Goal setting | Conducted in person in Mandarin (or preferred language relative to the individual) Initial assessment normative data adapted to Asian population group in testing protocols resource Complete pre- and post-evaluation data outlining impact of program on social inclusion |

| Exercise sessions | Capped at 12 participants per session In-person exercise sessions consist of a warm-up, followed by a combination of aerobic, resistance, balance, and flexibility exercises tailored to participants’ abilities, followed by a cool-down period | Capped at 12 participants per session delivered in Mandarin Trainers encouraged to factor social inclusion into structure of sessions, e.g., group activities, “pairing” participants together, the general promotion of conversation, and relationship building |

| Education sessions | 6 × 30 min person-centered education sessions on various lifestyle and diabetes management topics delivered in person | 4 × 30 min person-centered education sessions on various lifestyle management topics delivered in person in Mandarin Removal of diabetes-specific information and topics to ensure suitability to general population Focus on prevention of conditions like diabetes through physical activity, healthy eating, and mental health management |

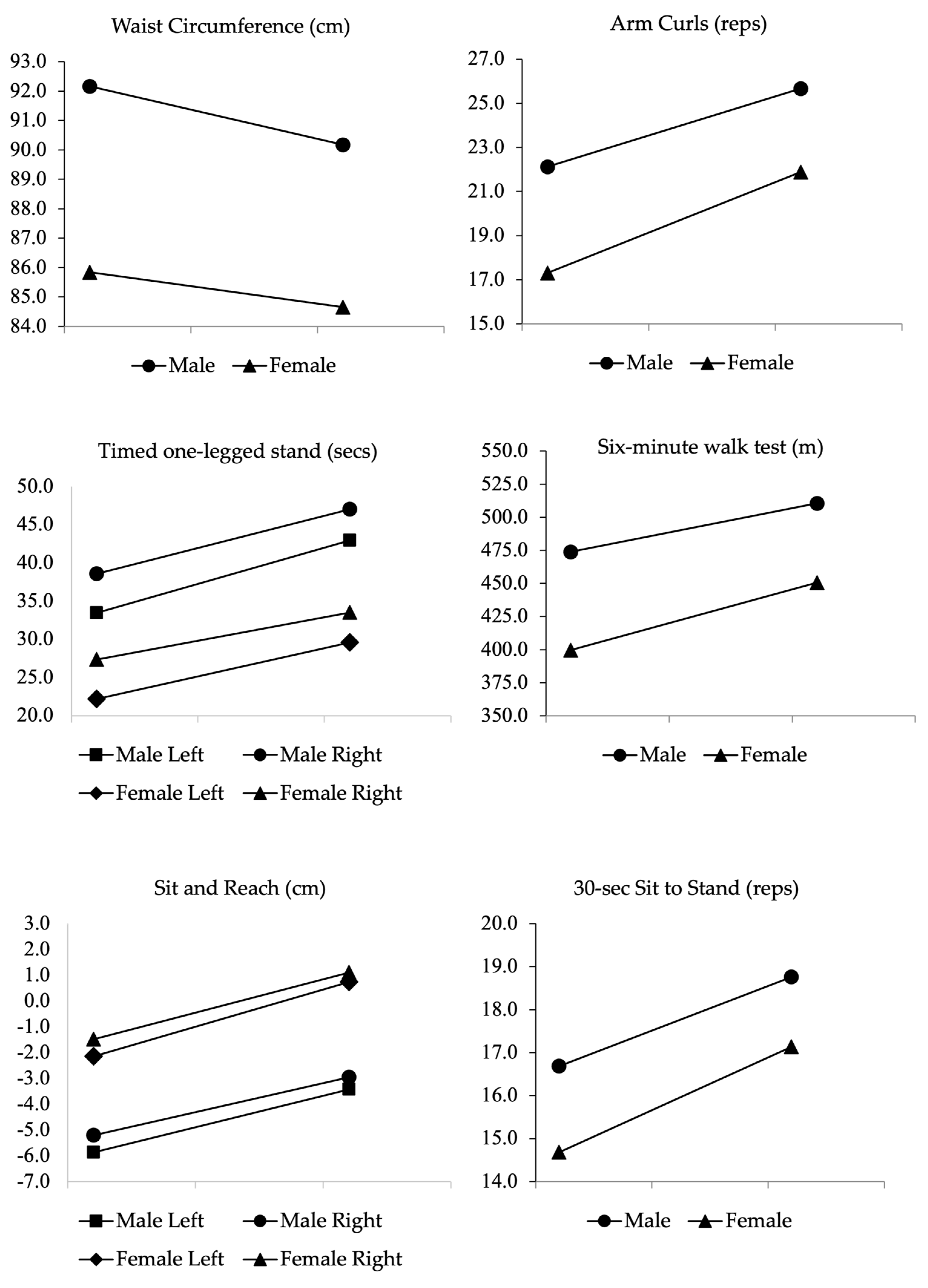

| Male (n = 38) | Female (n = 63) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 9-Week Mean (SD) | 99% CI; p-Value | Baseline Mean (SD) | 9-Week Mean (SD) | 99% CI; p-Value | |

| Weight (kg) | 70.7 (8.2) | 70.6 (8.1) | [−0.41–0.60]; 0.61 | 56.2 (7.0) | 56.04 (6.9) | [−0.16–0.47]; 0.19 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.71 (2.0) | 24.68 (1.9) | [−0.14–0.21]; 0.61 | 23.05 (3.0) | 22.99 (3.0) | [−0.07–0.2]; 0.19 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92.17 (6.0) | 90.18 (6.0) | [0.23–3.75]; 0.004 | 85.85 (8.7) | 84.66 (8.5) | [0.47–1.9]; <0.001 |

| Sit and reach–left (cm) | −5.87 (9.1) | −3.42 (8.9) | [−3.96–-0.93]; <0.001 | −2.14 (8.9) | 0.74 (8.0) | [−4.08–−1.68]; <0.001 |

| Sit and reach–right (cm) | −5.2 (8.6) | −2.95 (8.2) | [−3.87–−0.63]; <0.001 | −1.49 (9.0) | 1.1 (8.3) | [−3.77–−1.42]; <0.001 |

| 30 sec sit to stand (reps) | 16.68 (4.8) | 18.76 (4.4) | [−3.47–−0.68]; <0.001 | 14.68 (4.7) | 17.13 (4.8) | [−3.32–−1.57]; <0.001 |

| One-legged stand–L (sec) | 33.45 (22.0) | 42.92 (21.6) | [−15.62–−3.33]; <0.001 | 22.16 (17.9) | 29.56 (20.7) | [−11.89–−2.90]; <0.001 |

| One-legged stand–R (sec) | 38.55 (22.3) | 47.03 (20.6) | [−14.78–−2.17]; <0.001 | 27.32 (22.2) | 33.48 (20.5) | [−9.89–−2.42]; <0.001 |

| Arm curl (reps) | 22.13 (4.8) | 25.66 (5.4) | [−5.43–−1.63]; <0.001 | 17.3 (5.4) | 21.89 (5.4) | [−5.83–−3.35]; <0.001 |

| Six-minute walk distance (m) | 474 (130.9) | 510.66 (128.2) | [−72.69–−0.63]; 0.01 | 399.54 (117.7) | 450.63 (138.5) | [−74.29–−27.9]; <0.001 |

| Male (n = 38) | Female (n = 63) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Count (%) | 9-Week Count (%) | p-Value | Baseline Count (%) | 9-Week Count (%) | p-Value | |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Normal (18.5–22.9) | 9 (24) | 9 (24) | 33 (52) | 33 (52) | ||

| Overweight (23.0–24.9) | 13 (34) | 13 (34) | 17 (27) | 17 (27) | ||

| Class I obesity (25–29.9) | 15 (39) | 15 (39) | 11 (18) | 11 (18) | ||

| Class II obesity (≥30) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | ||||||

| Normal range | 11 (29) | 16 (42) | 15 (24) | 17 (27) | ||

| Risk of chronic disease | 27 (71) | 22 (58) | 0.06 | 48 (76) | 46 (73) | 0.50 |

| Sit and reach (cm) | ||||||

| Below standard | 22 (58) | 19 (50) | 48 (76) | 43 (68) | ||

| Met or were above standard | 16 (42) | 19 (50) | 0.25 | 15 (24) | 20 (32) | 0.18 |

| 30 sec sit to stand (reps) | ||||||

| Below standard | 15 (40) | 6 (16) | 32 (51) | 19 (30) | ||

| Met or above standard | 23 (60) | 32 (84) | 0.12 | 31 (49) | 44 (70) | <0.001 |

| 30 sec arm curl (reps) | ||||||

| Below standard | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 23 (37) | 9 (14) | ||

| Met or above standard | 36 (95) | 38 (100) | 40 (63) | 54 (86) | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirwan, M.; Chiu, C.L.; Fermanis, J.; Allison, K.; Laing, T.; Gwynne, K. Culturally Adapted, Clinician-Led, Bilingual Group Exercise Program for Older Migrant Adults: Single-Arm Pre–Post-Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060888

Kirwan M, Chiu CL, Fermanis J, Allison K, Laing T, Gwynne K. Culturally Adapted, Clinician-Led, Bilingual Group Exercise Program for Older Migrant Adults: Single-Arm Pre–Post-Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060888

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirwan, Morwenna, Christine L. Chiu, Jonathon Fermanis, Katie Allison, Thomas Laing, and Kylie Gwynne. 2025. "Culturally Adapted, Clinician-Led, Bilingual Group Exercise Program for Older Migrant Adults: Single-Arm Pre–Post-Intervention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060888

APA StyleKirwan, M., Chiu, C. L., Fermanis, J., Allison, K., Laing, T., & Gwynne, K. (2025). Culturally Adapted, Clinician-Led, Bilingual Group Exercise Program for Older Migrant Adults: Single-Arm Pre–Post-Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060888