Predictors of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Long COVID: Systematic Review of Prevalence

Abstract

1. Introduction

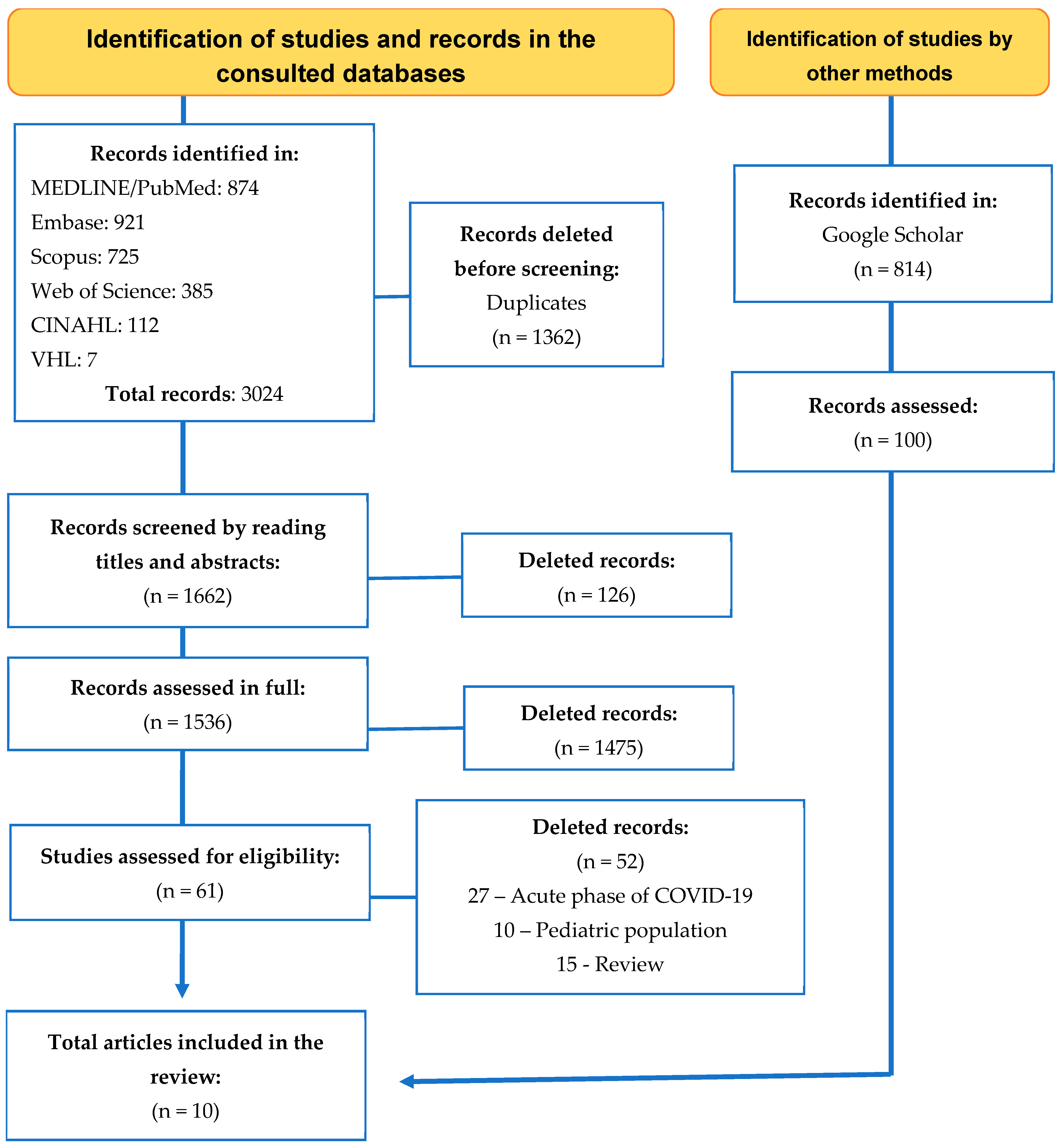

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc, H.C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G. Long COVID and its Management. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4768–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballering, A.V.; van Zon, S.K.R.; Hartman, T.C.O.; Rosmalen, J.G.M. Lifelines Corona Research Initiative. Persistence of somatic symptoms after COVID-19 in the Netherlands: An observational cohort study. Lancet 2022, 400, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Otterson, L. Post–COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18–64 and ≥65 years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Bowe, B.; Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Bosworth, M.L.; King, S.; Pouwels, K.B.; Glickman, M.; Nafilyan, V.; Zaccardi, F.; Khunti, K.; Alwan, N.A.; Walker, A.S. Risk of Long COVID in People Infected With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 After 2 Doses of a Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine: Community-Based, Matched Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macêdo Rocha, D.; Pedroso, A.O.; Sousa, L.R.M.; Gir, E.; Reis, R.K. Predictors for Anxiety and Stress in Long COVID: A Study in the Brazilian Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cano, H.J.; Moreno-Murguía, M.B.; Morales-López, O.; Crow-Buchanan, O.; English, J.A.; Lozano-Alcázar, J.; Somilleda-Ventura, S.A. Anxiety, depression, and stress in response to the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. Cir. Cir. 2020, 88, 562–568. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Quan, L.; Chavarro, J.E.; Slopen, N.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Koenen, K.C.; Kang, J.H.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Branch-Elliman, W.; Roberts, A.L. Associations of Depression, Anxiety, Worry, Perceived Stress, and Loneliness Prior to Infection With Risk of Post-COVID-19 Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Choi, D.; Lee, J.J. Depression, anxiety, and stress in Korean general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol. Health 2022, 44, e2022018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM 2020, 113, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Kulzhabayeva, D.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Gill, H.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Lui, L.M.; Cao, B.; Mansur, R.B.; Ho, R.C.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination for the prevention and treatment of long COVID: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 111, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.M.; Sousa, L.R.M.; Silveira, R.C.C.P.; Gir, E.; Reis, R.K. Anxiety, depression and stress in long COVID syndrome: A systematic review protocol. Cent. Open Sci. 2023, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, F.O. Estresse no Cotidiano. In Comércio e Representações; Pancast Ed.: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D.; Tripathy, S.; Kar, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Verma, S.K.; Kaushal, V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, M. Comparison of Prevalence and Associated Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among People Affected by versus People Unaffected by Quarantine During the COVID-19 Epidemic in Southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e924609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, D.L.; Holdsworth, L.; Jawad, N.; Gunasekera, P.; Morice, A.H.; Crooks, M.G. Post-COVID-19 Symptom Burden: What is Long-COVID and How Should We Manage It? Lung 2021, 199, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.G.; De Lorenzo, R.; Conte, C.; Poletti, S.; Vai, B.; Bollettini, I.; Melloni, E.M.T.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P.; et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Yao, Q.; Gu, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, P.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; et al. 1-Year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taquet, M.; Dercon, Q.; Luciano, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Husain, M.; Harrison, P.J. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: A 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanichkachorn, G.; Newcomb, R.; Cowl, C.T.; Murad, M.H.; Breeher, L.; Miller, S.; Trenary, M.; Neveau, D.; Higgins, S. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (Long Haul Syndrome): Description of a Multidisciplinary Clinic at Mayo Clinic and Characteristics of the Initial Patient Cohort. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, D.A.P.d.; Gomes, S.V.C.; Filgueiras, P.S.; Corsini, C.A.; Almeida, N.B.F.; Silva, R.A.; Medeiros, M.I.V.A.R.C.; Vilela, R.V.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Grenfell, R.F.Q. Long COVID-19 syndrome: A 14-months longitudinal study during the two first epidemic peaks in Southeast Brazil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Tomasoni, D.; Falcinella, C.; Barbanotti, D.; Castoldi, R.; Mulè, G.; Augello, M.; Mondatore, D.; Allegrini, M.; Cona, A.; et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 611.e6–611.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, S.J.; Winters, M.F.; Pizzagalli, D.A.; Olmstead, M.C. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: Evidence of mood & cognitive impairment. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 17, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsitani, L.; Vassalini, P.; Koukopoulos, A.; Borrazzo, C.; Alessi, F.; Di Nicolantonio, C.; Serra, R.; Alessandri, F.; Ceccarelli, G.; Mastroianni, C.M.; et al. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Among COVID-19 Survivors at 3-Month Follow-up After Hospital Discharge. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1702–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE | ((((((((((((“Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome”) OR (“Long-COVID”)) OR (“Post-COVID-19 syndrome”)) OR (“Long Haul Syndrome COVID-19”)) OR (“long-haul COVID”)) OR (“post-acute COVID syndrome”)) OR (“persistent COVID-19”)) OR (“long COVID”)) OR (“long haul COVID”)) OR (“chronic COVID syndrome”))) OR (“COVID survivor”)) AND ((((((Anxiety) OR (Anxiousness)) OR (Depression)) OR (“Depressive Symptoms”)) OR (((((“Stress Disorders, Traumatic”) OR (“Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”)) OR (“Traumatic Stress Disorder”)) OR (“Stress, Psychological”)) OR (“Psychological Stress”)))) |

| Web of Science | (ALL = (“Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome”) OR ALL = (“Long-COVID”) OR ALL = (“Post-COVID-19 syndrome”) OR ALL = (“Long Haul Syndrome COVID-19”) OR ALL = (“long-haul COVID”) OR ALL = (“post-acute COVID syndrome”) OR ALL = (“persistent COVID-19”) OR ALL = (“long COVID”) OR ALL = (“long haul COVID”) OR ALL = (“chronic COVID syndrome”) OR ALL = (“COVID survivor”)) AND (ALL = (Anxiety) OR ALL = (Anxiousness) OR ALL = (Depression) OR ALL = (“Depressive Symptoms”) OR ALL = (“Stress Disorders, Traumatic”) OR ALL = (“Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”) OR ALL = (“Traumatic Stress Disorder”) OR ALL = (“Stress, Psychological”) OR ALL = (“Psychological Stress”)) |

| Scopus | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Long-COVID”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Post-COVID-19 syndrome”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Long Haul Syndrome COVID-19”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“long-haul COVID”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“post-acute COVID syndrome”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“persistent COVID-19”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“long COVID”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“long haul COVID”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“chronic COVID syndrome”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“COVID survivor”))) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (anxiety) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (anxiousness) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (depression) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Depressive Symptoms”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Stress Disorders, Traumatic”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Traumatic Stress Disorder”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Stress, Psychological”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Psychological Stress”))) |

| Embase | (‘post-acute COVID-19 syndrome’ OR ‘long-COVID’ OR ‘long COVID’ OR ‘post-COVID-19 syndrome’ OR ‘long haul syndrome COVID-19’ OR ‘long-haul COVID’ OR ‘post-acute COVID syndrome’ OR ‘persistent COVID-19’ OR ‘long haul COVID’ OR ‘chronic COVID syndrome’ OR ‘COVID survivor’) AND (anxiety OR ‘anxiety disorder’ OR anxiousness OR depression OR ‘depressive symptoms’ OR ‘posttraumatic stress disorder’ OR ‘stress disorders, traumatic’ OR ‘stress disorders, post-traumatic’ OR ‘traumatic stress disorder’ OR ‘mental stress’ OR ‘stress, psychological’ OR ‘psychological stress’) |

| LILACS, BDENF and IBECS via VHL | ((“Síndrome pós-COVID-19”) OR (“Síndrome pós-aguda de COVID-19”) OR (“COVID longa”) OR (“Síndrome de longo curso COVID-19”) OR (“COVID-19 persistente”) OR (“COVID de longa duração”) OR (“síndrome de COVID crônica”) OR (“sobrevivente de COVID”) OR (“Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome”) OR (“Long-COVID”) OR (“Post-COVID-19 syndrome”) OR (“Long Haul Syndrome COVID-19”) OR (“long-haul COVID”) OR (“post-acute COVID syndrome”) OR (“persistent COVID-19”) OR (“long COVID”) OR (“long haul COVID”) OR (“chronic COVID syndrome”) OR (“COVID survivor”)) AND ((mh:(Ansiedade)) OR (Ansiedade) OR (Angústia) OR (mh:(Depressão)) OR (Depressão) OR (“Sintomas Depressivos”) OR (mh: (“Estresse Psicológico”)) OR (“Estresse Psicológico”) OR (Estresse) OR (Anxiety) OR (Anxiousness) OR (Depression) OR (“Depressive Symptoms”) OR (“Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”) OR (“Stress Disorders, Traumatic”) OR (“Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic”) OR (“Traumatic Stress Disorder”) OR (“Stress, Psychological”) OR (“Stress, Psychological”) OR (“Psychological Stress”)) |

| Author, Year, Periodical | Objective | Country | Design and Sample | Assessment Time Assessment Tool | Outcome (Prevalence) and Predictor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sykes DL et al. [21]. 2021 Lung | Report the lasting burden of symptoms in patients admitted with COVID-19 | England | Observational N = 134 Male: 65.7% Mean age: 59.6 Treated in wards: 80% Intensive Care Unit (ICU): 20% | 113 days after hospital discharge Standardized Assessment Form and 5-level EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D-5L) | Anxiety (47.8%) and depression (37.3%) Predictors: Being female There were no significant differences in symptom duration based on level of care, maximum oxygen, or respiratory support received |

| Huang et al. [22]. 2021 Lancet | Describe the long-term consequences in patients with COVID-19 who have been discharged from hospital | China | Cohort N = 1733 Male: 52% Mean age: 57.0 | 6 months after the onset of symptoms Self-reported symptoms questionnaire, EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, and EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) | Anxiety or depression (23%) Predictors: Being female, disease severity, use of supplemental oxygen |

| Mazza et al. [23]. 2020 Brain Behav Immun. | Investigate the psychopathological impact on COVID-19 survivors | Italy | Cross-sectional N = 402 Male: 56.7% Mean age: 57.80 | One month after hospital treatment Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZSDS), 13-item Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-13), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y (STAI-Y) | Anxiety (42%), depression (28%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (28%). Predictors: Being female, previous psychiatric diagnosis, home treatment |

| Huang et al. [24]. 2021 Lancet | Compare outcomes between 6 months and 12 months after symptom onset among hospital survivors with COVID-19 | China | Cohort 1276 Median age 59.0 years (IQR 49.0–67.0) 681 (53%) were men | 6 months and 12 months after symptom onset Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) score and HRQoL | 6 months Anxiety or depression (23%) 12 months Anxiety or depression (26%) Predictors: Being female, infection severity |

| Taquet et al. [25]. 2021 PLoS Med | Estimate the incidence, occurrence, and evolution of COVID-19 6 months after diagnosis | USA | Retrospective cohort N = 273,618 Female: 55.6% Mean age: 46.30 | 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis. TriNetX Analytics to analyze demographics, diagnoses, and measurements | Anxiety or depression (15.49%) Predictor: Young adults |

| Vanichkachorn et al. [26]. 2021 Mayo Clin Proc. | Describe the characteristics of prolonged symptoms after COVID-19 infection | USA | Cohort N = 100 Female: 68% Mean age: 45.40 | 93 days after infection Electronic Health Records, EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale | Depression or anxiety (34%) |

| Miranda et al. [27]. 2022 Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. | Analyze the profile and symptoms suggestive of Long COVID | Brazil | Longitudinal N = 646 Female: 53.9% Mean age: 50.26 | Up to 14 months Questionnaire and electronic medical records | Anxiety (7.1%) and depression (2.8%). Predictors: Age, disease severity, presence of comorbidities—high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, smoking, alcoholism |

| Bai et al. [28]. 2022 Clin Microbiol Infect | Identify the predictors of Long COVID | Italy | Prospective cohort N = 377 | 44 days Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R) | Anxiety (18.8%), depression (10.6%), post-traumatic stress disorder (31%) Predictors: Being female and advanced age |

| Lamontagne, et al. [29]. 2021 Brain Behavior I. Health | Analyze mood and cognitive functioning after COVID-19 infection | USA Canada | Cohort N = 100 Female: 58.0% Mean age: 30.80 | 1–4 months Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS), and the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ) | Anxiety (33%), perceived stress (23%), and depression (17%). Predictor: Headache in the acute phase |

| Tarsitani et al. [30]. 2021 J Gen Intern Med. | Assess the prevalence and risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection | Italy | Cohort N = 115 Male: 54% | 3 months PCL-5 | Post-traumatic stress disorder (10.4%) Predictor: Being female, previous psychiatric diagnosis, obesity |

| Study/Assessment Criteria | Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used to Measure the Condition? | Were Confounding Factors Identified? | Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sykes DL et al., 2021 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Huang et al., 2021 [22] | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5/8 |

| Mazza et al., 2020 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Huang et al., 2021 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Taquet et al., 2021 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Vanichkachorn et al., 2021 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Miranda et al., 2022 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Bai et al., 2022 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Lamontagne, et al., 2021 [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

| Tarsitani et al., 2021 [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6/8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha, D.d.M.; Pedroso, A.O.; Menegueti, M.G.; Silveira, R.C.d.C.P.; Sousa, L.R.M.; Gir, E.; Reis, R.K. Predictors of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Long COVID: Systematic Review of Prevalence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060867

Rocha DdM, Pedroso AO, Menegueti MG, Silveira RCdCP, Sousa LRM, Gir E, Reis RK. Predictors of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Long COVID: Systematic Review of Prevalence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060867

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha, Daniel de Macêdo, Andrey Oeiras Pedroso, Mayra Gonçalves Menegueti, Renata Cristina de Campos Pereira Silveira, Laelson Rochelle Milanês Sousa, Elucir Gir, and Renata Karina Reis. 2025. "Predictors of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Long COVID: Systematic Review of Prevalence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060867

APA StyleRocha, D. d. M., Pedroso, A. O., Menegueti, M. G., Silveira, R. C. d. C. P., Sousa, L. R. M., Gir, E., & Reis, R. K. (2025). Predictors of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Long COVID: Systematic Review of Prevalence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060867