The Body as a Battleground: A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Violence, Body Shaming, and Self-Harm in Adolescents with a History of Suicide Attempts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Purpose

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Setting and Data Source

3.2. Participants

3.3. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis and Frequencies

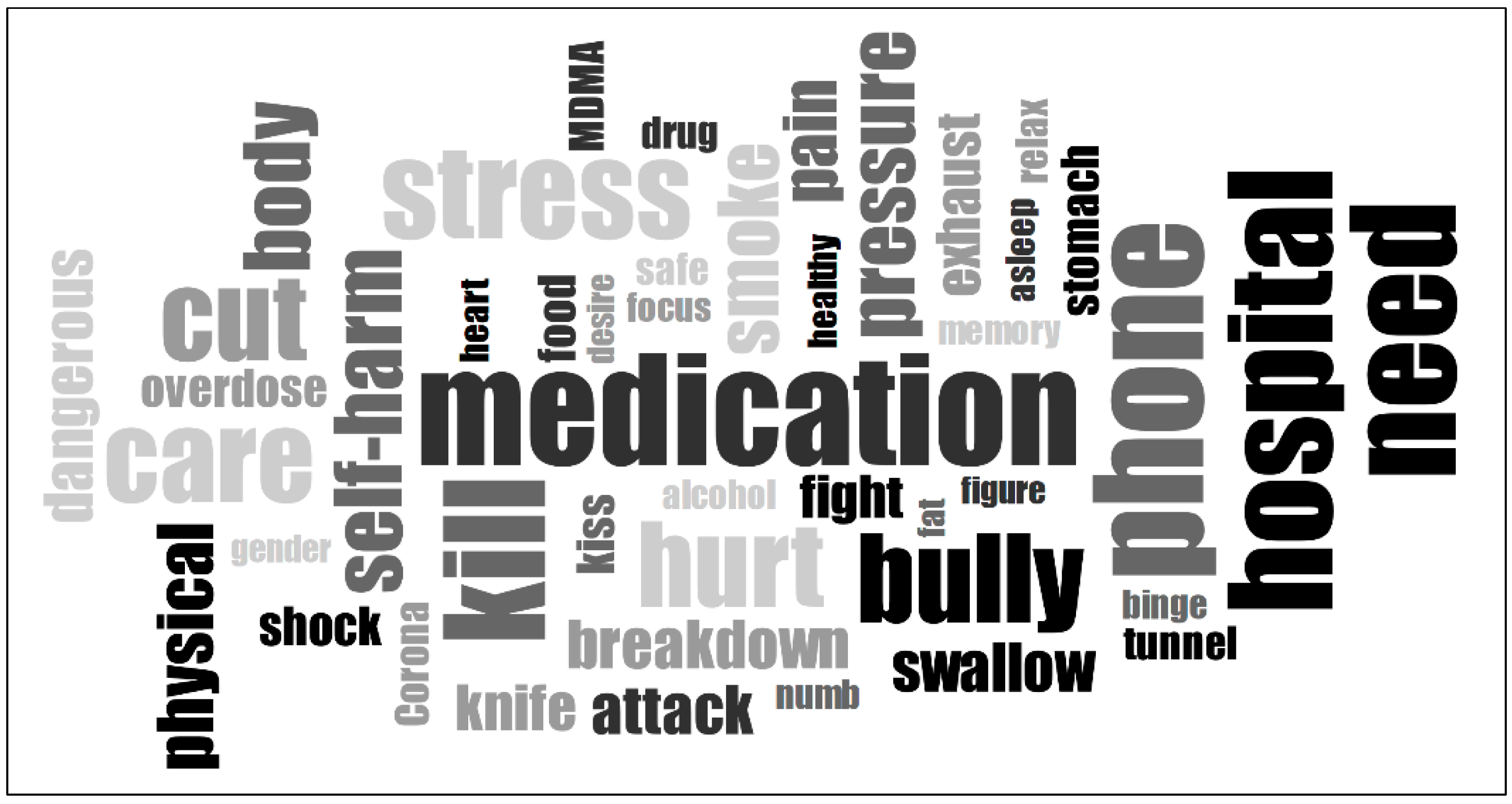

4.2. Linguistic Analysis (Word Cloud)

4.3. Content Analysis

“I asked myself why I was always unlucky. I had nothing but bad luck during this time after the suicide attempt. I was bullied, I was harassed, I was robbed, I was touched even though I didn’t want to be. I have experienced so much adversity that I asked myself again why I am still alive and why I continue to endure this. I actually wanted to die. I simply should not have survived”.(Participant Z003)

4.3.1. Violence and Traumatic Experiences

“But after one or two years, it wasn’t just light teasing anymore; it actually turned into bullying—with violence. […] I tried with all my energy not to show it at home, so that I wouldn’t be a burden. […] I used to lie and say I walked through some bushes, which is why I had scratches, and that I fell, which is why I was all bruised”.(Participant P001)

“At home, I was beaten by my parents and also brutally bullied. ((…)) It was also emotional abuse. After an argument, they ignored me for two weeks. Afterward, they acted as if it didn’t happen. So, it’s very toxic. […] And then I thought to myself, if life goes on like this and people treat me this way, why should I continue living? (--) That same year, I also attempted suicide”.(Participant Z001)

“My older brother tried to rape or sexually harass me. I don’t want to go into detail or determine exactly what it was because one is a crime, and the other is not. I think it’s normal after such things, but I couldn’t sleep anymore out of fear that it would happen again. […] I didn’t wake up the next morning right away, and when I did, I couldn’t move. I was completely paralyzed. I couldn’t sleep at all for the next few days. I kept trying to wash the dirt off my body. My dislike for my body became much stronger because I felt like it was now dirty or something. ((…)) Since I considered myself responsible for raising my brothers, I took the blame for what happened”.(Participant P050)

“And then I found out that I had been sexually harassed. A guy from my class took pictures of my butt and sent them around […] I used to sit next to him at school and he just took pictures of me and then texted strangers about raping me and that sort of things. And that completely destroyed my childish self. I was so little; I was 12 years old when that happened”.(Participant P043)

“I started to feel like people were following me all the time, like at the train station. […] I got stuck in this thought: “What if I have killed someone?” […] That’s how things got to the point where I didn’t want to live anymore”.(Participant P035)

“I had tried to run away and was already restrained in the ambulance, they restrained me again in the hospital, tying me to a bed. I didn’t want any more help—I just wanted to die. […] At home, I kept having flashbacks of how the police restrained me, how I actually felt in my body”.(Participant Z001)

“Then I ran out (of the isolation room) because I couldn’t stand being in there, as I have trauma from the isolation room. The nurses ran after me. Then I got angry and threw a chair […] I just screamed and raged, shaking with anger. They stood in front of me and I couldn’t talk to them. I just shouted at them”.(Participant Z002)

“Since then, I’ve had constant paranoia about being raped, which is why I’ve introduced almost obsessive control rituals, such as checking the door”.(Participant P050)

“I realized that he (the perpetrator) was doing similar things (sexual assault) to a friend of mine as well. So, we called the police again because we wanted to do something about it. And at some point, I realized that I had no control over it. Knowing that made everything worse because I couldn’t change it. And then I started having homicidal thoughts […] and I would think: “Oh, I’ll just take a knife to school and stab him”. My parents didn’t realize how serious I was about it”.(Participant P045)

4.3.2. Body Shaming and Body Dissatisfaction

“I also went through puberty earlier. That was in the 4th grade, while others were still so little, and I was already growing. I got wider hips and all that. The girls commented, “She’s wearing a bra” or “Ugh, she’s got her period”. And the boys laughed at my breasts. […] I never really liked my body. Then, during the quarantine (COVID-19), I gained weight. I was around 65 kg, and that was more on the overweight side, as my doctor confirmed. […] I didn’t like my body, and I also hid myself in big clothes and so on. At some point—at the end of September—I just stopped eating consciously. […] I lived almost exclusively on cornflakes and Diet Coke. […] In the end, I was even underweight”.(Participant P049)

“I just wanted to lose weight around my stomach. I saw it on the internet or in a fashion magazine and was like ’Wow, the model had a really nice flat stomach’. I knew that it was photoshopped or fake, but it still subconsciously influenced me to try to lose weight, and it just got worse and worse, so I got more and more restrictive”.(Participant P044)

“I was only five when I realized that my parents were talking critically about my sister’s body. […] That made an impression, and I memorized that calories are associated with something bad. […] My parents started body-shaming me when I was 11. When I was 12, it got really bad, and I had to get on the scales in front of my mum, and she said I already weighed more than her […] I started eating less and vomiting”.(Participant Z005)

4.3.3. Body-Damaging Coping Mechanisms

- (a)

- Self-harm

“I cut my neck once and thought, if it happens, it happens, and if not, then not. I did it several times, and I did the same to my arm, at the pulse artery”.(Participant Z005)

“I had to hurt myself because I wanted to see myself bleed or feel pain. But also, because I hate myself and I deserve it”.(Participant P047)

“I called for help. Every time I went to the toilet, the floor was covered in blood, at home, and at school […] Because when I cut myself, I see how it opens up, gapes, and the floor is covered in blood—that relaxes me […] I think it’s cool to show that, it’s actually similar to when you have some kind of addiction—you always have the urge to do it”.(Participant Z001)

- (b)

- Substance Use

“I developed sleep problems and could only sleep three hours a night, so I started smoking weed to cope […] Smoking weed also led to binge eating, causing me to gain 18 kg, which made me feel extremely uncomfortable in my own body […] I used cannabis to escape reality. Eventually, I realized I had to stop because my school performance was deteriorating—my grades kept worsening”.(Participant Z013)

“My only medication is smoking weed, which I actually do every day now. I can sleep better, and I’m in a world where nothing bothers me, and all the problems feel less drastic. It’s much more relaxed, and I don’t always have to think about what’s wrong”.(Participant P043)

“I started using alcohol and cannabis when I was 16. I moved to stronger drugs like LSD later. I used them weekly, and at some point, I even started drinking at school. I had the urge to do it, often with friends who also felt this urge”.(Participant Z003)

“I started with marijuana and progressed to cocaine, MDMA, and LSD. Simply to feel some form of pleasure. That went on for quite a long time, and at some point, I got nasal injuries […] During my last MDMA trip, I hallucinated about my dead grandfather—3 pills at once. I ended up on a bridge, and my friend had to restrain me because I was already leaning over the railing”.(Participant Z034)

- (c)

- Eating Disorders

“I was so afraid of gaining weight that I would vomit after binge eating. I began to develop brutal strategies. If I ate too much, I would vomit. If I did something bad, I would hurt myself. And if I did something wrong, I wanted to kill myself. Those were always my solutions”.(Participant P049)

“I managed to control myself for quite a long time. I would describe myself as very ambitious and a perfectionist, which I maintained for a long time. I ate nothing but corn waffles and similar stuff for days and months”.(Participant P049)

“I noticed that I had gained weight. My plan had failed. I gained 6 kg, and that’s quite a lot for my anorexia. I went home and decided to take painkillers. That was the first thing that came to my mind because I couldn’t control my eating. I felt hungry and I couldn’t resist. And then I swallowed eight 500 mg tablets […] Then, I spent a night in the intensive care unit. I hoped to stay there because I don’t know why, and it may sound sick, but I liked being there. I was with the supervisor, and I got full attention, and getting attention has always been a great need of mine”.(Participant P044)

4.3.4. Acute Physical Warning Signs

“I was completely gone; I don’t know what I did then. I had already been sitting there for two hours, and at some point, I asked, ‘What did I actually do?’ […] Then I suddenly noticed that my shoe was wet and that I had torn out my nail. I was in a suicidal mode. But somehow, it was almost robotic. I saw the rope, I saw the table, and I thought, “Oh, I could hang myself”—and just did it”.(Participant P001)

“I thought I was not needed at all. Basically, I am just a burden to the people around me. And I was like, okay, I don’t want this anymore. I’m tired […] A switch had flipped inside me, and I had no desire anymore. I didn’t want to go to school or anywhere else—I just wanted to leave and took the pills”.(Participant P032)

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

- The Influence of Experienced Violence and Trauma

- The Role of Body Dissatisfaction

- Body-damaging Consequences and Coping Mechanisms

- Self-harm was frequently described as a coping strategy providing temporary relief and a means of managing self-hatred. Several adolescents reported that displaying their scars of self-harm was the only way their distress was recognized, which eventually led to supportive interventions.

- Substance use was often used to numb emotional pain or escape from reality, which in some cases, led to impulsive suicide attempts under the influence of substances. Given the fragile mental health of these participants, it is not surprising that some developed substance use disorders that further impaired their ability to regulate emotions and behavior. The co-occurrence of suicidal ideation and substance use constitutes a particularly high-risk constellation, as the disinhibiting effects of substances can lower the threshold for impulsive suicide attempts and attenuate the innate fear of death, thereby further compromising internal protective barriers and increasing the likelihood of suicidal behaviors.

- Eating disorders frequently served as a means to manage body dissatisfaction or to fulfill a desire for control. The battle against hunger often resulted in perilous cycles of self-punishment and feelings of inadequacy, ultimately including suicidal acts. The significance of eating disorders aligns with the findings of a meta-analysis conducted by Amiri and Khan [29], which revealed an interplay between eating disorders and suicidal behavior, while suicidal ideation was prevalent in 60% of individuals with eating disorders, and suicide attempts were reported in 25% of this population.

- Acute Physical Warning Signs

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

5.3. Implications and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AdoASSIP | Adolescent Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program |

| ASSIP | Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program |

| GAT-2 | “Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2” (Discourse and Conversation-Analytic Transcription System 2) |

| LSD | Lysergic Acid Diethylamide |

| M | Mean |

| MDMA | 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

| n | Sample |

| N | Population |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

Appendix A

Additional Thematic Codebooks

- Reported Stressors

- -

- Psychosocial stressors

- -

- Intrapersonal stressors (e.g., emotional states)

- -

- Performance and future-related pressure

- -

- Stressful live events

- -

- Societal and structural stressors

- -

- Contagion of suicidal ideation (peers, family, media)

- Narrative Styles and Peculiarities

- -

- Onset of symptomatology

- -

- Suicide as relief

- -

- Minimization of suicidality

- -

- Victim positioning

- -

- Dysfunctional vs. functional reflection

- -

- Optimism despite crisis

- -

- Narrative emotionality (e.g., crying, irony)

- Description of Suicidality

- -

- First suicidal thoughts

- -

- Planning and method

- -

- Suicide attempt context (e.g., at home, during hospitalization)

- Post-Attempt Dynamics

- -

- Help seeking

- -

- Social responses

- -

- Medical treatment

- External Influences

- -

- Therapy experiences

- -

- Institutional measures (e.g., placement)

- Demographics, Diagnoses, and Symptom Patterns

References

- WHO. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 9789241564779. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Mental Health of Adolescents; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barrense-Dias, Y.; Chok, L.; Surís, J.-C. A Picture of the Mental Health of Adolescents in Switzerland and Liechtenstein; Unisanté–Centre Universitaire de Médecine Générale et Santé Publique: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylor, E.M. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2023, 72, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Burnett, S.; Dahl, R.E. The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010, 31, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.W.; Wood, A.M.; Maltby, J.; Taylor, P.J.; Tai, S. The prospective role of defeat and entrapment in depression and anxiety: A 12-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 216, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupariello, F.; Curti, S.M.; Coppo, E.; Racalbuto, S.S.; Di Vella, G. Self-harm risk among adolescents and the phenomenon of the “Blue Whale Challenge”: Case series and review of the literature. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 64, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Kuo, P.-H. Effects of perceived stress and resilience on suicidal behaviors in early adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackin, D.M.; Perlman, G.; Davila, J.; Kotov, R.; Klein, D.N. Social support buffers the effect of interpersonal life stress on suicidal ideation and self-injury during adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamarro, A.; Díaz-Moreno, A.; Bonilla, I.; Cladellas, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Limonero, J.T. Stress and suicide risk among adolescents: The role of problematic internet use, gaming disorder and emotional regulation. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, L.; Ebner, C.; Leo, K.; Lindenberg, K. Emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression, anxiety, aggression, and addiction in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2023, 30, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Bo, A.; Liu, T.; Zhang, P.; Chi, I. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisopoulou, T.; Varvogli, L. Stress management methods in children and adolescents: Past, present, and future. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 96, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahar, N.-e.; Saman, M.; Sarwat, Y.; Zaman, K. Role of Self-esteem and Social Support on Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Adolescents. Res. Sq. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yüksel Doğan, R.; Metin, E.N. Exploring the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction in adolescents: The role of social competence and self-esteem. Child Indic. Res. 2023, 16, 1453–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendirkıran, G.; Bilgin, H. The effect of mindfulness intervention on high school students’ eating habits and body image perceptions. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 29707–29723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, G.S.; Sazma, M.A.; Yonelinas, A.P. The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.J.; Nowson, C.A. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition 2007, 23, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, B.; Grealish, A.; Leamy, M. The beauty and the beast of social media: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the impact of adolescents’ social media experiences on their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Liu, R.; Jung, Y.; Barry, A.; Park, J.H. Sex differences among US high school students in the associations of screen time, cyberbullying, and suicidality: A mediation analysis of cyberbullying victimization using the Youth Risk Behavioural Surveillance Survey 2021. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 34, e2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Amit, N.; Suen, M.W.Y. Psychological factors as predictors of suicidal ideation among adolescents in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, N.M.; Brausch, A.M. Body dissatisfaction and symptoms of bulimia nervosa prospectively predict suicide ideation in adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, H.-S.; Chae, H.W. Height and subjective body image are associated with suicide ideation among Korean adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1172940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Rodrigues, T. Being bullied and feeling ashamed: Implications for eating psychopathology and depression in adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. 2015, 44, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Media pressures, internalization of appearance ideals and disordered eating among adolescent girls and boys: Testing the moderating role of body appreciation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, S.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. The impact of teasing and bullying victimization on disordered eating and body image disturbance among adolescents: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 985–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Khan, M.A. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, suicide mortality in eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Disord. 2023, 31, 487–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Moyer, A. Childhood sexual abuse and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Maté, G. When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress; Vintage Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castellví, P.; Miranda-Mendizábal, A.; Parés-Badell, O.; Almenara, J.; Alonso, I.; Blasco, M.; Cebrià, A.; Gabilondo, A.; Gili, M.; Lagares, C. Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.A.; Colburn, D. Independent and cumulative effects of recent maltreatment on suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm in a national sample of youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Harrer, S.; Zwald, M.L.; Leemis, R.W.; Holland, K.M.; Stone, D.M.; Harrison, K.M.; Swedo, E.A. Association of recent violence encounters with suicidal ideation among adolescents with depression. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e231190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, T.; Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Rudd, M.D. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M. Diathesis-Stress Models; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Large, M.; Galletly, C.; Myles, N.; Ryan, C.J.; Myles, H. Known unknowns and unknown unknowns in suicide risk assessment: Evidence from meta-analyses of aleatory and epistemic uncertainty. BJPsych Bull. 2017, 41, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodway, C.; Tham, S.-G.; Turnbull, P.; Kapur, N.; Appleby, L. Suicide in children and young people: Can it happen without warning? J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmond, J.; Kornhaber, R.; Visentin, D.; Cleary, M. A qualitative systematic review of experiences and perceptions of youth suicide. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Russell, A.; Mandy, W.; Butler, C. The phenomenology of gender dysphoria in adults: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 80, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunold, C.; Papandreou, A. Gesundheit von Schüler*innen der Stadt Zürich: Resultate der Befragung Schuljahr 2022/23. 2023. Available online: https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/de/aktuell/publikationen/2023/gesundheitsbefragung-jugendliche.html (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Singh, S.; Thompson, C.J.; Kak, R.; Smith, L.N.; Quainoo, N. Impact of body weight perceptions and electronic bullying on suicide-related risk behaviors among youth: Results from youth risk behavior surveillance system, 2015. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, M.N.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Ramirez, A.; McPherson, C.; Anderson, A.; Munir, A.; Patten, S.B.; McGirr, A.; Devoe, D.J. Non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal thoughts and behaviors in individuals with an eating disorder relative to healthy and psychiatric controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Qian, Y.; Fei, W.; Tian, S.; Geng, Y.; Wang, S.; Pan, C.-W.; Zhao, C.-H.; Zhang, T. Bullying victimization and suicide attempts among adolescents in 41 low-and middle-income countries: Roles of sleep deprivation and body mass. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1064731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Fatima, Y.; Pandey, S.; Tariqujjaman, M.; Cleary, A.; Baxter, J.; Mamun, A.A. Pathways linking bullying victimisation and suicidal behaviours among adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 302, 113992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Michel, K. AdoASSIP Therapiemanual—Ein Präventionsprogramm für Jugendliche nach einem Suizidversuch. 2025; in submission. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd, M.D. The suicidal mode: A cognitive-behavioral model of suicidality. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2000, 30, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysin-Maillart, A.; Soravia, L.; Schwab, S. Attempted suicide short intervention program influences coping among patients with a history of attempted suicide. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, F. Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. Sozialwissenschaftliche Prozessanalyse. Grund. Qual. Sozialforsch. 2016, 1, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ronksley-Pavia, M.; Grootenboer, P. Insights into disability and giftedness: Narrative methodologies in interviewing young people identified as twice exceptional. In Narrative Research in Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Muylaert, C.J.; Sarubbi, V., Jr.; Gallo, P.R.; Neto, M.L.R.; Reis, A.O.A. Narrative interviews: An important resource in qualitative research. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.; Barker, P. The persistence of memory: Using narrative picturing to co-operatively explore life stories in qualitative inquiry. Nurs. Inq. 2007, 14, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, K.; Valach, L. The Narrative Interview with the Suicidal Patient; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Selting, M.; Auer, P.; Barth-Weingarten, D.; Bergmann, J.R.; Bergmann, P.; Birkner, K.; Couper-Kuhlen, E.; Deppermann, A.; Gilles, P.; Günthner, S. Gesprächsanalytisches transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung Online-Z. Verbalen Interakt. 2009, 10, 353–402. [Google Scholar]

- Selting, M.; Barth-Weingarten, D. New Perspectives in Interactional Linguistic Research; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- VERBI, MAXQDA 2022; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeepL Pro, Version X.X; DeepL SE: Cologne, Germany, 2024.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT (Mar 14 Version) [Large Language Model]. 2023. Available online: https://chat.openai.com (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Scite_. Scite AI. 2025. Available online: https://scite.ai/assistant (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Frazier, P.A. Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, P.; Bartels, M.B.; Kieslich, M. Diagnostik und Signifikanzbeurteilung bei Verdacht auf sexuelle Gewalt im Kindes-und Jugendalter. Klin. Pädiatr. 2021, 233, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerson, O.; Baguley, T.; O’Connor, D.B. Childhood trauma and suicide. Crisis 2023, 44, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, H. The impact and long-term effects of childhood trauma. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: A summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenman, P.S.; Renzi, A.; Monaco, S.; Luciani, F.; Di Trani, M. How does trauma make you sick? The role of attachment in explaining somatic symptoms of survivors of childhood trauma. Healthcare 2024, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, M.; Valenza, M.; Iazzolino, A.M.; Longobardi, G.; Di Stefano, V.; Visalli, G.; Steardo, L.; Scuderi, C.; Manchia, M.; Steardo, L., Jr. Exploring the interplay between complex post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder severity: Implications for clinical practice. Medicina 2024, 60, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, A.; Trekels, J.; Eggermont, S. Preadolescents’ reliance on and internalization of media appearance ideals: Triggers and consequences. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 1074–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullsperger, J.M.; Nikolas, M.A. A meta-analytic review of the association between pubertal timing and psychopathology in adolescence: Are there sex differences in risk? Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Nazari, N.; Griffiths, M.D. Self-compassion moderates the association between body dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation in adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 2371–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatcharoenwitthaya, K.; Niltwat, S. The impact of lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of adolescents. Siriraj Med. J. 2022, 74, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, C.M.; dos Santos, J.d.S.; de Paula, E.L.; Oliveira, B.L.; da Costa, G.S.; dos Anjos Santana, E.; de Simões, V.d.A.; de Mattos, B.K.; Guglielmo, L.G.A.; dos Santos Silva, R.J. Association between body dissatisfaction, physical activity and mental health indicators in Brazilian adolescents. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2024, 58, 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, S.E.; Glenn, C.R.; Klonsky, E.D. Is non-suicidal self-injury an “addiction”? A comparison of craving in substance use and non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 197, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Colino, L.; Fajardo, L.; Perteguer-Barrio, R.; De Leon, J. The addictive model of self-harming (non-suicidal and suicidal) behavior. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, G.; Atkin, T.; Zytynski, T.; Wang, S.; Askari, S.; Boruff, J.; Ware, M.; Marmorstein, N.; Cipriani, A.; Dendukuri, N. Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciwoniuk, N.; Wayda-Zalewska, M.; Kucharska, K. Distorted body image and mental pain in anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodell, L.P.; Cheng, Y.; Wildes, J.E. Psychological impairment as a predictor of suicide ideation in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, S.; do Céu Salvador, M. Depression in institutionalized adolescents: The role of memories of warmth and safeness, shame and self-criticism. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornioli, A.; Lewis-Smith, H.; Slater, A.; Bray, I. Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: A prospective study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; McClure, Z.; Tylka, T.L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Body appreciation and its psychological correlates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image 2022, 42, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelef, L. The gender paradox: Do men differ from women in suicidal behavior? J. Men’s Health 2021, 17, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, G. Interpretive Social Research: An Introduction; Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, K.; Valach, L.; Gysin-Maillart, A. A novel therapy for people who attempt suicide and why we need new models of suicide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Participants with Code (n/N) | Overall Frequency of Code (N) |

|---|---|---|

| 50% (11/22) | 21 |

| 1a. Body Dissatisfaction | 31.8% (7/22) | 12 |

| 1b. Experiences of Body Shaming by Adults | 18.2% (4/22) | 5 |

| 1c. Experiences of Body Shaming by Peers | 31.8% (7/22) | 8 |

| 22.7% (5/22) | 85 |

| 2a. Verbal Abuse and Bullying | 72.7% (16/22) | 42 |

| 2b. Violence by Peers | 45.5% (10/22) | 10 |

| 2c. Violence by Adults | 27.3% (6/22) | 13 |

| 2d. Sexual Violence (e.g., Sexual Abuse) | 22.7% (5/22) | 13 |

| 59.1% (13/22) | 33 |

| 72.7% (16/22) | 45 |

| 86.4% (19/22) | 119 |

| 5a. Overburdening Responsibility | 40.9% (9/22) | 13 |

| 5b. Performance Pressure | 81.8% (18/22) | 51 |

| 50.0% (11/22) | 23 |

| 45.5% (10/22) | 59 |

| 7a. Stress from Weight Gain | 22.7% (5/22) | 7 |

| 7b. Fear of Gaining Weight/Calories | 18.2% (4/22) | 6 |

| 7c. Distorted Body Image | 13.6% (3/22) | 3 |

| 7d. Binge Eating | 13.6% (3/22) | 4 |

| 7e. Purging Behaviors | 22.7% (5/22) | 7 |

| 7f. Restrictive Eating/Anorexia | 36.4% (8/22) | 17 |

| 63.6% (14/22) | 59 |

| 8a. Alcohol Use | 18.2% (4/22) | 5 |

| 8b. Cannabis Use | 22.7% (5/22) | 13 |

| 8c. Tobacco Use | 22.7% (5/22) | 6 |

| 8d. Harder Substance Use | 13.6% (3/22) | 9 |

| 8e. Problematic Media Use | 40.9% (9/22) | 11 |

| 8f. Addiction | 22.7% (5/22) | 8 |

| 77.3% (17/22) | 80 |

| 9a. Lack of Physical Activity | 31.8% (7/22) | 14 |

| 9b. Absenteeism and Lack of Structure | 40.9% (9/22) | 18 |

| 9c. Neglect of Self-Care (e.g., Body Hygiene) | 18.2% (4/22) | 6 |

| 90.9% (20/22) | 110 |

| 10a. Suicidal Mode (Physical Aspects only) | 86.4% (19/22) | 70 |

| 10b. Somatic Pain or Discomfort | 27.3% (6/22) | 7 |

| 10c. Tremors, Panic Attacks, and Restlessness | 36.4% (8/22) | 10 |

| 10d. Numbness or Physical Insensibility | 31.8% (7/22) | 8 |

| 10e. Physical Exhaustion | 9.1% (2/22) | 2 |

| 10f. Acute Sleep and Eating Disorders | 22.7% (5/22) | 5 |

| 10g. Language Limitations (e.g., Mutism) | 18.2% (4/22) | 6 |

| 10h. Extreme Sensory Sensations (Hot/Cold) | 9.1% (2/22) | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizk-Hildbrand, M.; Semple, T.; Preisig, M.; Haeberling, I.; Smigielski, L.; Pauli, D.; Walitza, S.; Kleim, B.; Berger, G.E. The Body as a Battleground: A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Violence, Body Shaming, and Self-Harm in Adolescents with a History of Suicide Attempts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060859

Rizk-Hildbrand M, Semple T, Preisig M, Haeberling I, Smigielski L, Pauli D, Walitza S, Kleim B, Berger GE. The Body as a Battleground: A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Violence, Body Shaming, and Self-Harm in Adolescents with a History of Suicide Attempts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060859

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizk-Hildbrand, Marianne, Tara Semple, Martina Preisig, Isabelle Haeberling, Lukasz Smigielski, Dagmar Pauli, Susanne Walitza, Birgit Kleim, and Gregor E. Berger. 2025. "The Body as a Battleground: A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Violence, Body Shaming, and Self-Harm in Adolescents with a History of Suicide Attempts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060859

APA StyleRizk-Hildbrand, M., Semple, T., Preisig, M., Haeberling, I., Smigielski, L., Pauli, D., Walitza, S., Kleim, B., & Berger, G. E. (2025). The Body as a Battleground: A Qualitative Study of the Impact of Violence, Body Shaming, and Self-Harm in Adolescents with a History of Suicide Attempts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060859