Dementia Education and Training for In-Patient Health Care Support Workers in Acute Care Contexts: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Evaluation

Abstract

1. Background

Aim

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. The Intervention

- What are the levels of dementia knowledge, attitudes, and confidence among acute care support staff?

- Is DWEAC an effective educational intervention to improve dementia knowledge, attitudes, confidence, and person-centred care practices?

- How do acute care support staff perceive the content and quality of DWEAC?

- How does DWEAC need to be tailored further to ensure relevance for acute care support staff?

2.3. Sampling and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.1.1. Participant Demographics

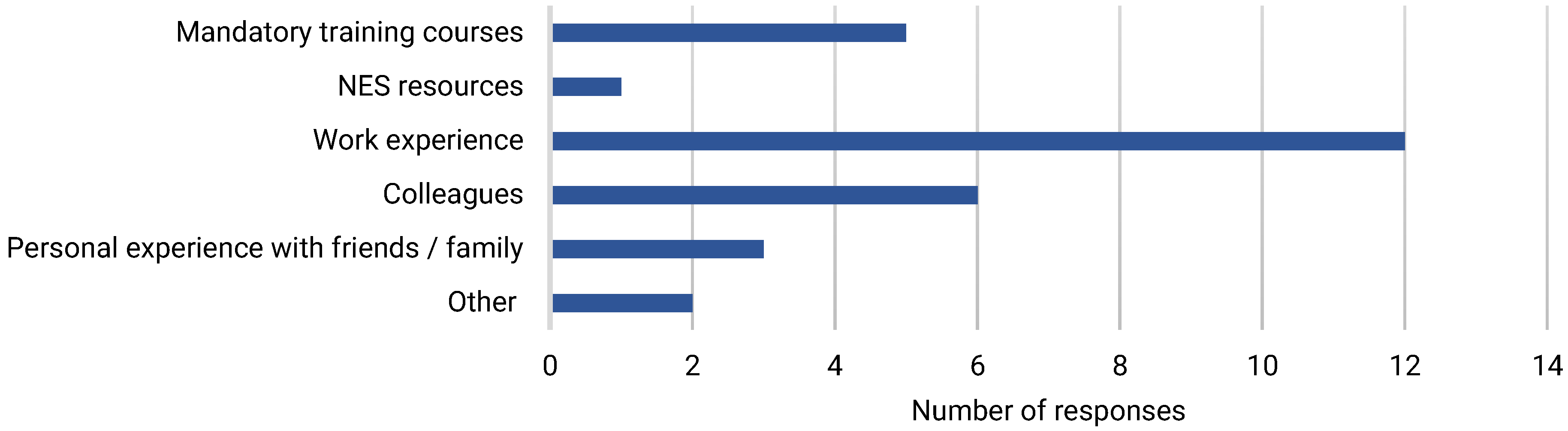

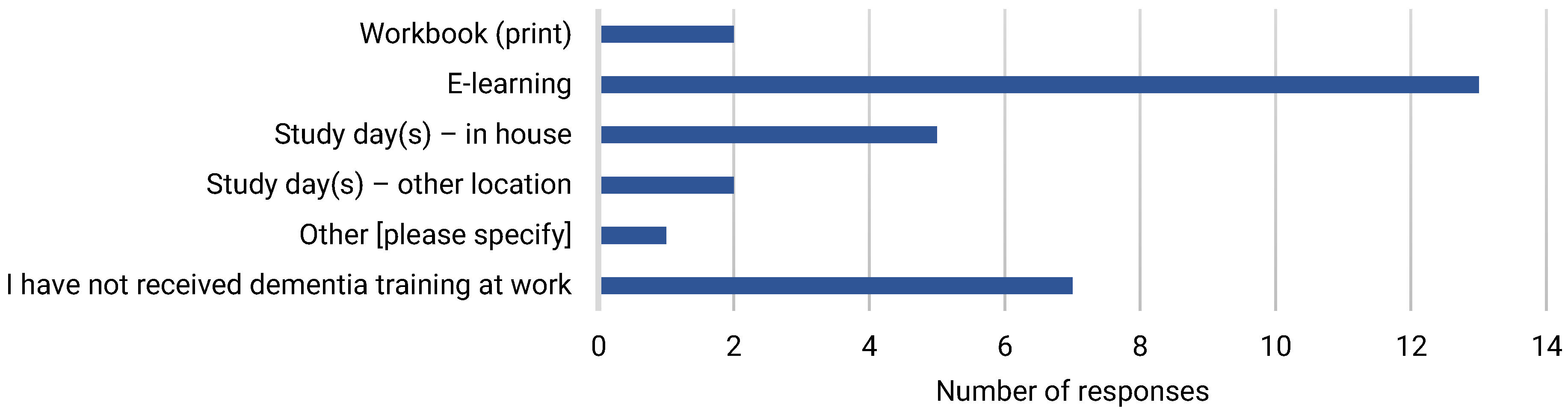

3.1.2. Experience of Dementia Care and Motivation for Learning

3.1.3. Dementia Knowledge

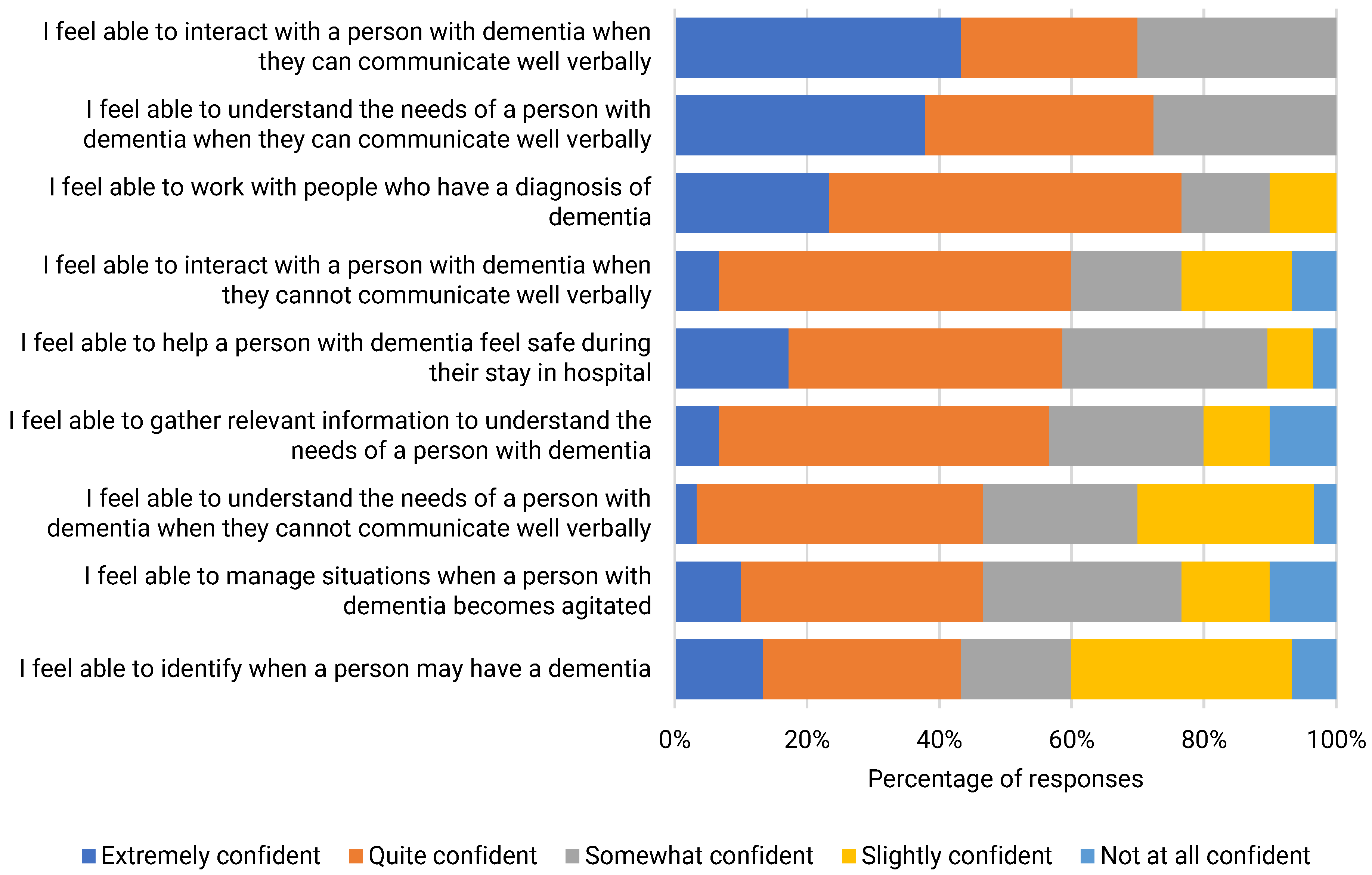

3.1.4. Dementia Care Confidence

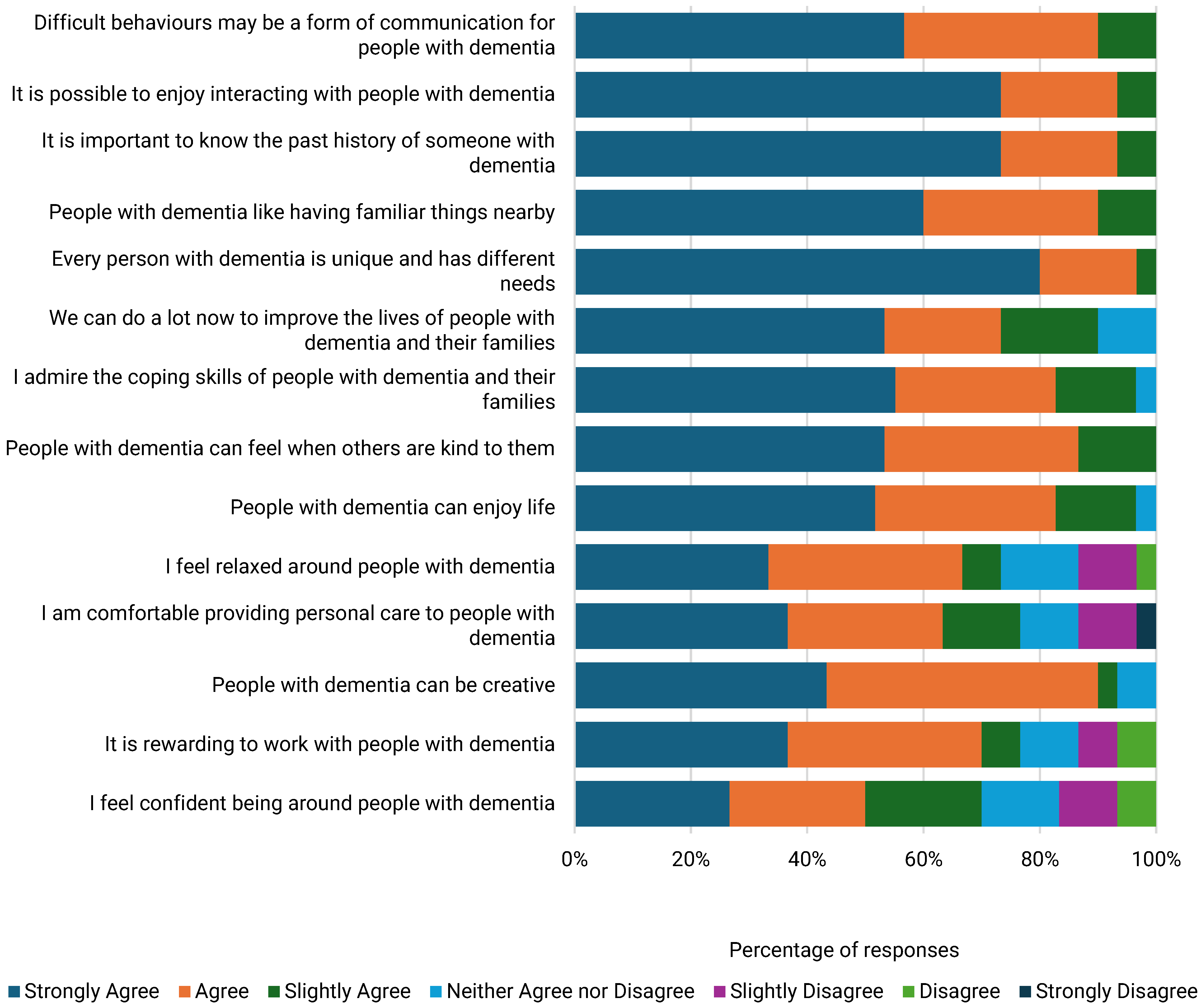

3.1.5. Dementia Care Attitudes

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Participants

3.2.2. Themes

3.2.3. Dementia Care Practice in the Acute Care Setting

3.2.4. Motivation for Attending DWEAC

“Also, for the job that I was doing because where I am now, albeit that I’m in a [acute] ward, our ward’s fast becoming, on a daily basis, just an MOE ward”.P2.

“I did a one-day thing, in fact it wasn’t even a whole day … it was within the [Hospital], but it wasn’t very detailed”.P1.

“Rather than just touching on the surface, I wanted to get more in-depth information about different types and, you know, and just to also improve my skills when dealing, my knowledge when dealing with these patients, you know, and hopefully being able to help them, you know, and I wouldn’t say understand but, you know, like to be able to like communicate better with them and have a better understanding of what they’re going through”.P2.

“My mum’s got dementia so … trying to deal with my mum like better, you know, and maybe understanding what she’s going through … trying to take away bits and pieces”.P2.

3.3. A Four-Level Evaluation of DWEAC

3.3.1. Satisfaction

3.3.2. Learning Gains

3.3.3. Behaviours

“I would have just been going on my instinct and just tapping into who’s been looking after him and reading about what matters to him in his wee folder”.P2.

“My first point of contact would have been going to my nurse in charge or the nurse who’s looking after that patient”.P2.

“I would deal with her a bit better and with more understanding … more empathy”.P3.

3.3.4. Results

“I’d been put on a different base and the relative asked if I could go and work on the other base because her mum seemed much, more settled when I was around … what an honour that was”.P1.

“For you giving me the opportunity to be on this course, I’ve now passed a lot of that information on, on the ward, since I’ve been back on the ward”.P2.

“I’ve already started putting a booklet together for the setting”.P1.

“I like a display … I think visual stuff I’m better at … it encourages conversations…people have been asking me, coming up to me and asking me questions”.P2.

“When I finished the course … my Band 7 had asked me would I do a presentation to the team … I did a presentation for the team a couple of weeks ago which seemed to go down really quite well”.P3.

“It would depend on how many were there … I don’t mind doing it for kind of the smaller groups … bigger groups, that would maybe kind of phase me but, you know, smaller groups… I wouldn’t be phased by it”.P3.

3.4. Mixed Methods Interpretation [Please See Supplementary Files S1–S3]

3.4.1. The Need for Dementia Education in Acute Care

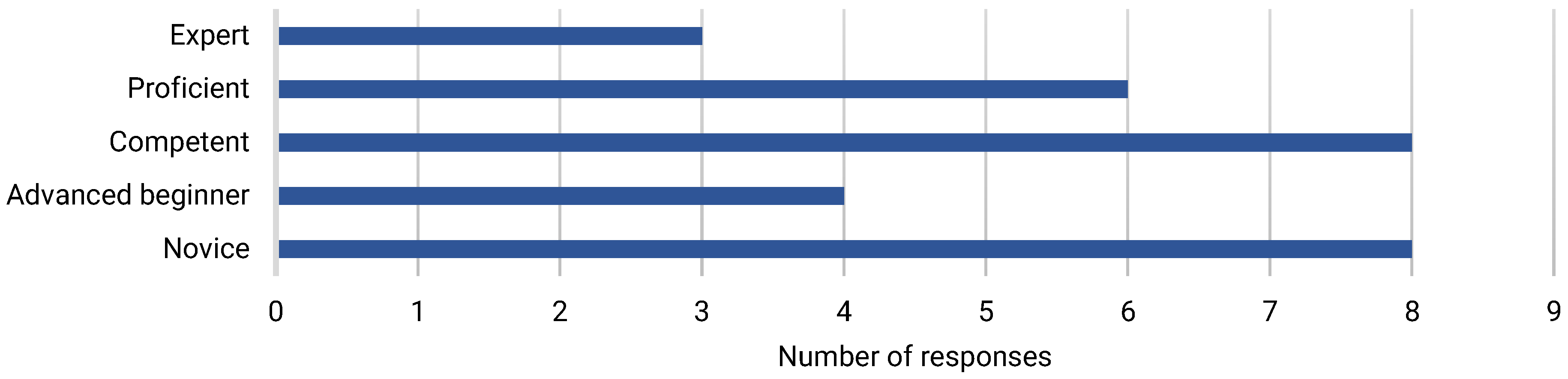

3.4.2. Dementia Care Confidence and Competence Before DWEAC

3.4.3. Dementia Care Confidence and Competence After DWEAC

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Implications for Environmental and Public Health Practice

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Orginization. Dementia. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. Dementia Statistics Hub. Available online: https://dementiastatistics.org/about-dementia/prevalence-and-incidence/?_gl=1*1p5laji*_ga*MTY0MTM0ODQ2OC4xNzA5ODEyNzQ3*_ga_TR76MGPH49*MTcwOTgxMjg4NC4xLjEuMTcwOTgxNDE3NS41NS4wLjA (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Wittenberg, R.; Hu, B.; Barraza-Araiza, L.; Rehill, A. Projections of Older People with Dementia and Costs of Dementia Care in the United Kingdom, 2019–2040. 2019. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/cpec/assets/documents/cpec-working-paper-5.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Chen, Y.; Bandosz, P.; Stoye, G.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lobanov-Rostovsky, S.; French, E.; Kivimaki, M.; Livingston, G.; Liao, J.; et al. Dementia incidence trend in England and Wales, 2002–2019, and projection for dementia burden to 2040: Analysis of data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e859–e867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, C. The Economic Impact of Dementia [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.carnallfarrar.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Alz-report.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. National Audit of Dementia Care in General Hospitals 2018–2019: Round Four Audit Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/national-audit-of-dementia/r4-resources/reports%2D%2D-core-audit/national-audit-of-dementia-round-4-report-online.pdf?sfvrsn=f75c5b75_12 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Chater, K.; Hughes, N. Strategies to deliver dementia training and education in the acute hospital setting. J. Res. Nurs. 2013, 18, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Long, S.; Vincent, C. How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013, 106, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Deming, K.A.; Danaher, T.S. Improving Nonclinical and Clinical-Support Services: Lessons from oncology. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 2, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowdell, F. The care of older people with dementia in acute hospitals. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2010, 5, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evripidou, M.; Charalambous, A.; Middleton, N.; Papastavrou, E. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes about dementia care: Systematic literature review. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 55, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.H.P.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Goldberg, R.J.; Yuan, Y.; Gurwitz, J.H.; Nguyen, H.L.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes and Confidence in Providing Dementia Care to Older Adults Among Nurses Practicing in Hanoi, Vietnam: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2024, 19, e12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dookhy, J.; Daly, L. Nurses’ experiences of caring for persons with dementia experiencing responsive behaviours in an acute hospital: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2021, 16, e12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2010; The Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2010.

- Scottish Government. Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2013–2016. 2013. Available online: https://webarchive.nrscotland.gov.uk/3000/https://www.gov.scot/Resource/0042/00423472.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Scottish Government. National Dementia Strategy: 2017–2020. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-national-dementia-strategy-2017-2020/pages/3/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Scottish Government. New Dementia Strategy for Scotland: Everyone’s Story. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/new-dementia-strategy-scotland-everyones-story/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Scottish Government. Promoting Excellence 2021: A Framework for All Health and Social Services Staff Working with People with Dementia, Their Families and Carers. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/promoting-excellence-2021-framework-health-social-services-staff-working-people-dementia-families-carers/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Baillie, L.; Sills, E.; Thomas, N. Educating a health service workforce about dementia: A qualitative study. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2016, 17, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surr, C.; Gates, C.; Irving, D.; Oyebode, J.; Smith, S.; Parveen, S.; Drury, M.; Dennison, A. Effective Dementia Education and Training for the Health and Social Care Workforce: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 966–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Sarah, J.S.; Sass, C.; Jan, R.O.; Capstick, A.; Dennison, A.; Surr, C.A. Impact of dementia education and training on health and social care staff knowledge, attitudes and confidence: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e039939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toubøl, A.; Moestrup, L.; Thomsen, K.; Ryg, J.; Hansen, D.L.; Foldager, M.; Jakobsen, S.; Nielsen, D.S. The impact of an education intervention on the approach of hospital staff to patients with dementia in a Danish general hospital setting: An explanatory sequential mixed-methods study. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 42, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Standard of Care for Dementia in Scotland. 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/standards-care-dementia-scotland-action-support-change-programme-scotlands-national-dementia-strategy/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Macaden, L. Being Dementia Smart (BDS): A Dementia Nurse Education Journey in Scotland. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2016, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaden, L.; Muirhead, K. Dementia Education for Workforce Excellence: Evaluation of a Novel Bichronous Approach. Healthcare 2024, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, G.; Agnelli, J. Person-centred care for people with dementia: Kitwood reconsidered. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 30, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, M.R.; Davies, S.; Brown, J.; Keady, J.; Nolan, J. Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: A new vision for gerontological nursing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC. Online Surveys. 2023. Available online: https://onlinesurveys.jisc.ac.uk/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Elvish, R.; Burrow, S.; Cawley, R.; Harney, K.; Graham, P.; Pilling, M.; Gregory, J.; Roach, P.; Fossey, J.; Keady, J. ‘Getting to Know Me’: The development and evaluation of a training programme for enhancing skills in the care of people with dementia in general hospital settings. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.L.; McFadden, S.H. Development and Psychometric Validation of the Dementia Attitudes Scale. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 2010, 454218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, D. Great Ideas Revisited. Techniques for Evaluating Training Programs. Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s four-level model. Train. Dev. 1996, 50, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Adewuyi, M.; Morales, K.; Lindsey, A. Impact of experiential dementia care learning on knowledge, skills and attitudes of nursing students: A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 62, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surr, C.A.; Sass, C.; Burnley, N.; Drury, M.; Smith, S.; Parveen, S.; Burden, S.; Oyebode, J. Components of impactful dementia training for general hospital staff: A collective case study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukadam, N.; Sampson, E.L. A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older general hospital inpatients. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surr, C.; Gates, C. What works in delivering dementia education or training to hospital staff? A critical synthesis of the evidence. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 75, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossard Saxell, T.; Ingvert, M.; Lethin, C. Facilitators for person-centred care of inpatients with dementia: A meta-synthesis of registered nurses’ experiences. Dementia 2021, 20, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, T.; Gardiner, P. Communication and interaction within dementia care triads: Developing a theory for relationship-centred care. Dementia 2005, 4, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.; Nolan, M.; Reid, D.; Enderby, P. Using the Senses Framework to achieve relationship-centred dementia care services: A case example. Dementia 2008, 7, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwadiugwu, M. Early-onset dementia: Key issues using a relationship-centred care approach. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 97, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austen, L. Increasing emotional support for healthcare workers can rebalance clinical detachment and empathy. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, M.; Gurbutt, R.; Carson, J. Qualities, teaching, and measurement of compassion in nursing: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 63, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasper, A. Strategies to promote the emotional health of nurses and other NHS staff. Br. J. Nurs. 2020, 29, 248–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, K.; Macaden, L.; Smyth, K.; Chandler, C.; Clarke, C.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C. Establishing the effectiveness of technology-enabled dementia education for health and social care practitioners: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.E.; Wong Shee, A.; West, E.; Morvell, M.; Theobald, M.; Versace, V.; Yates, M. Impact of the Dementia Care in Hospitals Program on acute hospital staff satisfaction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, P.; Vandenhouten, C.; Purvis, S.; Zupanc, T. The Impact of Education on Certified Nursing Assistants’ Identification of Strategies to Manage Behaviours Associated with Dementia. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2018, 34, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, E.L.; Vickerstaff, V.; Lietz, S.; Orrell, M. Improving the care of people with dementia in general hospitals: Evaluation of a whole-system train-the-trainer model. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkioka, M.; Schneider, J.; Kruse, A.; Tsolaki, M.; Moraitou, D.; Teichmann, B. Evaluation and Effectiveness of Dementia Staff Training Programs in General Hospital Settings: A Narrative Synthesis with Holton’s Three-Level Model Applied. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 1089–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C.A.; Hojat, M.; Gonnella, J.S. Volunteer bias in medical education research: An empirical study of over three decades of longitudinal data. Med. Educ. 2007, 41, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimova, S.; Prideaux, R.; Ball, S.; Harshfield, A.; Carpenter, A.; Marjanovic, S. Enabling NHS staff to contribute to research: Reflecting on current practice and informing future opportunities. Rand Health Q. 2020, 8, RR-2679. [Google Scholar]

- Surr, C.A.; Parveen, S.; Smith, S.J.; Drury, M.; Sass, C.; Burden, S.; Oyebode, J. The barriers and facilitators to implementing dementia education and training in health and social care services: A mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia. Prepared to Care: Challenging the Dementia Skill Gap; All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Dementia: A Public Health Priority; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Towards a Dementia-Inclusive Society: WHO Toolkit for Dementia-Friendly Initiatives (DFIs); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

| Classroom Sessions | Associated Workbooks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | Themes | Duration | Facilitator | |

| 1 | Introduction to DWEAC and Workbooks | 30 min | 1, 2 | |

| The Human Brain | 1 h | 1 | Dementia Care Essentials | |

| Memory & Sensory Changes in Dementia | 1 h | 1 | ||

| Insights on Living with Dementia | 30 min | 1, 2 | ||

| Person-centred Dementia Care | 30 min | 1, 2 | ||

| Living with Dementia | 45 min | 3 | ||

| Family Carers’ Perspectives | 45 min | 3 | ||

| 2 | Stages of the Dementia Journey | 1 h | 1, 2 | Dementia Care Priorities |

| Dementia, Delirium, and Depression | 45 min | 1, 2 | ||

| Stress & Distress in Dementia | 45 min | 1 | ||

| Dementia Inclusive and Enabling Environments | 1 h | 1 | ||

| 3 | Advanced Dementia a | 45 min | 1, 2 | Dementia Care Enablers |

| Relationship-centred Dementia Care b | 45 min | 1 | ||

| Commitments & Pledges for Dementia Care | 1 h | 1, 2 | ||

| Age | n [%] | Years of Acute Care Experience | n [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16–20 | 1 [3.3] | 1–5 years | 14 [46.7] |

| 21–30 | 5 [16.7] | 5–10 years | 7 [23.3] |

| 31–40 | 5 [16.7] | 10–20 years | 5 [16.7] |

| 41–50 | 12 [40.0] | More than 20 years | 3 [10.0] |

| 51–60 | 3 [10.0] | Missing | 1 [3.3] |

| >60 | 4 [13.3] | ||

| Department | n [%] | Years of dementia care experience | n [%] |

| General Medicine | 11 [36.7] | 1–5 years | 12 [40.0] |

| Medicine of the Elderly | 11 [36.7] | 5–10 years | 5 [16.7] |

| Department of Clinical Neuroscience | 3 [10.0] | 10–20 years | 8 [26.7] |

| Orthopaedics | 3 [10.0] | More than 20 years | 5 [16.7] |

| Stroke Medicine | 2 [6.7] | ||

| Role | n [%] | Frequency of dementia care | n [%] |

| Clinical Support Worker | 14 [46.7] | On a daily basis | 12 [40.0] |

| Healthcare Assistant/Care Assistant | 5 [16.7] | At least on a weekly basis | 13 [43.3] |

| OT Assistant | 3 [10.0] | At least on a monthly basis | 4 [13.3] |

| PT Assistant | 2 [6.7] | Missing | 1 [3.3] |

| Other | 6 [20.0] | ||

| Experience of informal dementia care | n [%] | Attended DWEAC training | n [%] |

| Yes | 5 [16.7] | Yes | 4 [13.3] |

| No | 23 [76.7] | No | 26 [86.7] * |

| Missing | 2 [6.7] | ||

| All Participants | Did Not Attend DWEAC | Attended DWEAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Correct n [%] | Response n | Correct n [%] | Response | Correctn n [%] | |

| 1. Anger and hostility occur in dementia mostly because the “aggression” part of the brain has been affected | 30 | 18 [60] | 26 | 16 [62] | 4 | 2 [50] |

| 2. Dementia is a general term which refers to a number of different diseases | 30 | 23 [77] | 26 | 20 [77] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 3. Dementia can be caused by a number of small strokes | 30 | 18 [60] | 26 | 17 [65] | 4 | 1 [25] |

| 4. People with dementia will eventually lose all their ability to communicate | 30 | 17 [57] | 26 | 14 [54] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 5. A person with dementia’s history and background plays a significant part in their behaviour | 28 | 23 [82] | 24 | 20 [83] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 6. A person with dementia is less likely to receive pain relief than a person without dementia when they are in hospital | 30 | 23 [77] | 26 | 19 [73] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 7. People with dementia who are verbally aggressive nearly always become physically aggressive | 30 | 23 [77] | 26 | 20 [77] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 8. When people with dementia walk around it is usually aimless | 29 | 22 [76] | 25 | 19 [76] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 9. Permanent changes to the brain occur in most types of dementia | 30 | 29 [97] | 26 | 25 [96] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 10. Brain damage is the only factor that is responsible for the way people with dementia behave | 30 | 28 [93] | 26 | 24 [92] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 11. Physical pain may result in a person with dementia becoming aggressive or withdrawn | 30 | 29 [97] | 26 | 26 [100] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 12. People who have dementia will usually show the same symptoms | 30 | 25 [83] | 26 | 22 [85] | 4 | 3 [75] |

| 13. Currently, most types of dementia cannot be cured | 30 | 30 [100] | 26 | 26 [100] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 14. People with dementia never get depressed | 30 | 29 [97] | 26 | 25 [96] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 15. My perception of reality may be different from that of a person with dementia | 29 | 29 [100] | 25 | 25 [100] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| 16. It is possible to catch dementia from other people | 30 | 28 [93] | 26 | 24 [92] | 4 | 4 [100] |

| Did Not Attend [n = 26] | Attended [n = 4] | |

|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | |

| I feel able to … | ||

| Identify when a person may have a dementia | 3 [2,4] | 4 [3.5,4] |

| Understand the needs of a person with dementia when they cannot communicate well verbally | 3 [2,4] | 4 [4,4] |

| Manage situations when a person with dementia becomes agitated | 3 [2.25,4] | 4 [3.75,4] |

| Interact with a person with dementia when they cannot communicate well verbally | 4 [2.25,4] | 4 [4,4] |

| Work with people who have a diagnosis of dementia | 4 [3.25,4.75] | 4 [4,4] |

| Help a person with dementia feel safe during their stay in hospital | 4 [3,4] | 3.5 [3,4] |

| Gather relevant information to understand the needs of a person with dementia | 4 [3,4] | 4 [3.5,4] |

| Interact with a person with dementia when they can communicate well verbally | 4 [3,5] | 4 [4,4.25] |

| Understand the needs of a person with dementia when they can communicate well verbally | 4 [3,5] | 4 [4,4.25] |

| Total | 4 [3,4] | 4 [4,4] |

| Did Not Attend [n = 26] | Attended [n = 4] | |

|---|---|---|

| Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | |

| Positive items | ||

| I feel confident being around people with dementia | 5 [4,6] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| It is rewarding to work with people with dementia | 6 [4.25,7] | 6.5 [6,7] |

| People with dementia can be creative | 6 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| I am comfortable providing personal care to people with dementia | 6 [4.25,6.75] | 7 [7,7] |

| I feel relaxed around people with dementia | 6 [4,6.75] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| People with dementia can enjoy life | 6 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| People with dementia can feel when others are kind to them | 6 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| I admire the coping skills of people with dementia and their families | 6.5 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| We can do a lot now to improve the lives of people with dementia and their families | 6.5 [5,7] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| Every person with dementia is unique and has different needs | 7 [7,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| People with dementia like having familiar things nearby | 7 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| It is important to know the past history of someone with dementia | 7 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| It is possible to enjoy interacting with people with dementia | 7 [6,7] | 7 [7,7] |

| Difficult behaviours may be a form of communication for people with dementia | 7 [6,7] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| Negative items | ||

| I feel frustrated because I do not know how to help people with dementia and their families | 3 [3,5.75] | 5 [3.5,6.25] |

| I feel afraid being around people with dementia | 6 [4,6] | 6 [6,6.25] |

| I cannot imagine taking care of someone with dementia | 6 [4,6] | 6.5 [6,7] |

| I would avoid an agitated person with dementia | 6 [4,6] | 7 [7,7] |

| I feel uncomfortable being around people with dementia | 6 [4,6] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| I am not very familiar with dementia | 6 [5,6] | 7 [6.75,7] |

| All items | 6 [6,6.625] | 7 [7,7] |

| Quote | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| “When the pandemic hit … I wasn’t aware as of as many people, but now … if you went round every ward, they’ve all got, you know, quite a healthy number of elderly people with dementia”. P2. | Interview participants described an increasing prevalence of patients with dementia in acute care wards, which were considered similar to MOE wards in terms of patient demographics, with this trend more apparent since the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| “The beauty of the clinical support worker is they’re afforded the time more to talk to the patient because they’re making the bed, they’re doing the personal care … you help them, you sit them down, you do all the things, but you learn an awful lot about them when you’re able to talk to them”. P2. | ACSS were well placed to provide good-quality dementia care given their unique opportunities to get to know patients well. |

| “The holistic side wasn’t there, and not because nurses and doctors don’t want to do that, they just are so driven by time and pressure … we’re bursting at the seams with people coming in the hospital”. P2. | The participants often strived to provide good-quality dementia care but were often constrained by busy workloads and time demands in practice. |

| “Some people are just what I would call textbook nurses … they’ve gave them their medicine … they’ve gave them their fluids … they’ve gave them a basin … to me are not going the extra mile they need to go to find out what it is actually going on because, again, they’re, for me, removed from the dementia side”. P2. | A significant barrier was the task-orientated nature of the acute care environment. |

| “I don’t think I thought I’d meet so many people, get so much, you know, true life representation of dementia, I thought it was more sort of lecture based if you know what I mean”. P1 |

| “I found it really, really insightful … because of the depth it went into”. P3. |

| “I think that was really useful … we had the time … after the first day, right, you go away and you think well there’s questions that I’ll ask the second”. P3. “Having the workbooks to fall back on, or read before, you know, before coming … and we’ve obviously got that as a reference now as well”. P3. |

| “I think it was good the way it was broken down into the different sections and it made you think about things a bit differently rather than seeing it holistically”. P3. |

| “I like things in front of me … I would have liked a sort of workbook so that I could highlight in … something printed”. P1. |

| “It’s great getting information, you know, online … but it’s good to be able to say to somebody, well, you know, hang on a minute I don’t agree with that … everybody’s got a different skills level, everybody got a different, you know, take on it, or experience”. P3. |

| “To know that if I’ve got any concerns … I would like to be able to think that I could come to you and say well how do we deal with this?”. P2. |

| “Listening to their story and, you know, having them standing in front of you, it wasn’t a piece of paper you were reading … they were standing in front of you … it gave you a complete insight as to day-to-day life actually living, and actually, it was quite positive, they were very positive, it wasn’t all negative” P1. |

| “I felt annoyed with myself because, you know, here’s these two wonderful people standing at the front, you know, sharing their story with us and I’m bubbling in the background”. P1. “They were bringing a tear to your eye … just because of their stories”. P3. |

| Theme | Code | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Dementia subtypes | “I didnae realise there was so many different types of dementia, I mean I knew some of them cause there’s a kind of common ones right, but I didnae realise that there was, you know, there was so many”. P3. |

| Person-centred care | The course did get me thinking a lot more about the person-centred … it just kind of came to the forefront … given me a better understanding of what the person-centred approach was going to be”. P3. | |

| Relationship-centred care | “The information you’re going to find out from their families could be key”. P1. | |

| Informal dementia care | “I think it’s Lewy bodies that my mum’s got … it gave me a wee bit more understanding … it’s helped me professionally and yeah in my personal life”. P3. | |

| General | “Oh, it’s like night and day … I feel like I have a much better understanding now”. P1. | |

| Skills | Communication | “It’s trying to listen to people and take on board what their saying rather than just your perception”. P3. |

| General | “I feel much more equipped to be able to do my job and care for them the best way I can”. P1. | |

| Confidence | General | “I’m less scared when I go in for a shift and I look at the handover sheet and it says that somebody’s got dementia … not scared for myself but scared in the fact that I’m not going to do the best by that patient”. P1. |

| Attitudes | General | “Hopefully my attitude and my dealing with people has changed for the better… I do have a bit more understanding, a bit more empathy for them”. P3. |

| Mary is an 86-year-old lady living on her own with moderate dementia. She has been admitted to an MOE ward following a fall at home. She has bruises and pain but is deemed medically fit and is waiting for a care package before discharge. Staff have noticed a change in Mary’s presentation over the past 24 h. She is much more confused and believes that someone in the ward is trying to hurt her. What would be your assessment of Mary’s situation? | BEFORE DWEAC “Before the training you would have just maybe just put it down to her, you know, dementia, and not looked at the bigger picture” |

| AFTER DWEAC “I would have thought, kind of put the dementia to one side and … maybe took a urine sample and seen if she had a urine infection or delirium maybe” |

| On a visit to my dad Charlie, he was particularly agitated, ill at ease with himself and everyone around him. His language was ‘industrial’ at best. Staff thought that he was being aggressive but chose to ignore his agitation rather than try to get to the cause. Charlie was totally deaf in one ear and had a hearing aid in his other ear. We were asked whether it would be ok to increase his medication to sedate him more. What do you think is happening for Charlie, and how would you manage this situation? | BEFORE DWEAC “I would be just going with my instinct with someone like that before this training course” |

| AFTER DWEAC “If they canny walk properly there’s a reason … if they canny hear there’s a reason … if their eyesight’s bad and they’ve not got their glasses, where’s their glasses? If they’ve not got their teeth, how can they eat their food? So, all those things became more evident” |

| Elsie is 82 years old and usually lives at home on her own following the death of her husband five years ago. She was diagnosed with moderate dementia three years ago and has a package-of-care three times a day. Her two daughters and three grandchildren visit regularly and help with appointments and shopping. Elsie was admitted to hospital five weeks ago after developing sepsis secondary to an untreated urinary tract infection and has started to recover well. There have been incidents over the past five days where Elsie has been found banging on the ward door and trying to leave. Elsie believes that she needs to get home to collect her children from school. Attempts to reorientate Elsie have been unsuccessful and have resulted in her becoming very distressed and mistrusting of the ward staff. What do you think is happening for Elsie, and how would you manage this situation? | BEFORE DWAC “I might have just, you know, tried to … appease her, and just, you know, ‘right come on Elsie’, you know, ‘you need to come back to your room’, or … ‘come on get a cup of tea’ … trying to calm her down but just, you know, well yes calm her down … just trying to get her to settle down” |

| AFTER DWEAC “If I didnae already know what her family background was, trying to get her family story from her as much as you could” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macaden, L.; Muirhead, K.; MacArthur, J.; Blair, S. Dementia Education and Training for In-Patient Health Care Support Workers in Acute Care Contexts: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060860

Macaden L, Muirhead K, MacArthur J, Blair S. Dementia Education and Training for In-Patient Health Care Support Workers in Acute Care Contexts: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060860

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacaden, Leah, Kevin Muirhead, Juliet MacArthur, and Siobhan Blair. 2025. "Dementia Education and Training for In-Patient Health Care Support Workers in Acute Care Contexts: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Evaluation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060860

APA StyleMacaden, L., Muirhead, K., MacArthur, J., & Blair, S. (2025). Dementia Education and Training for In-Patient Health Care Support Workers in Acute Care Contexts: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060860