Longitudinal Associations Between Sources of Uncertainty and Mental Health Amongst Resettled Refugees During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

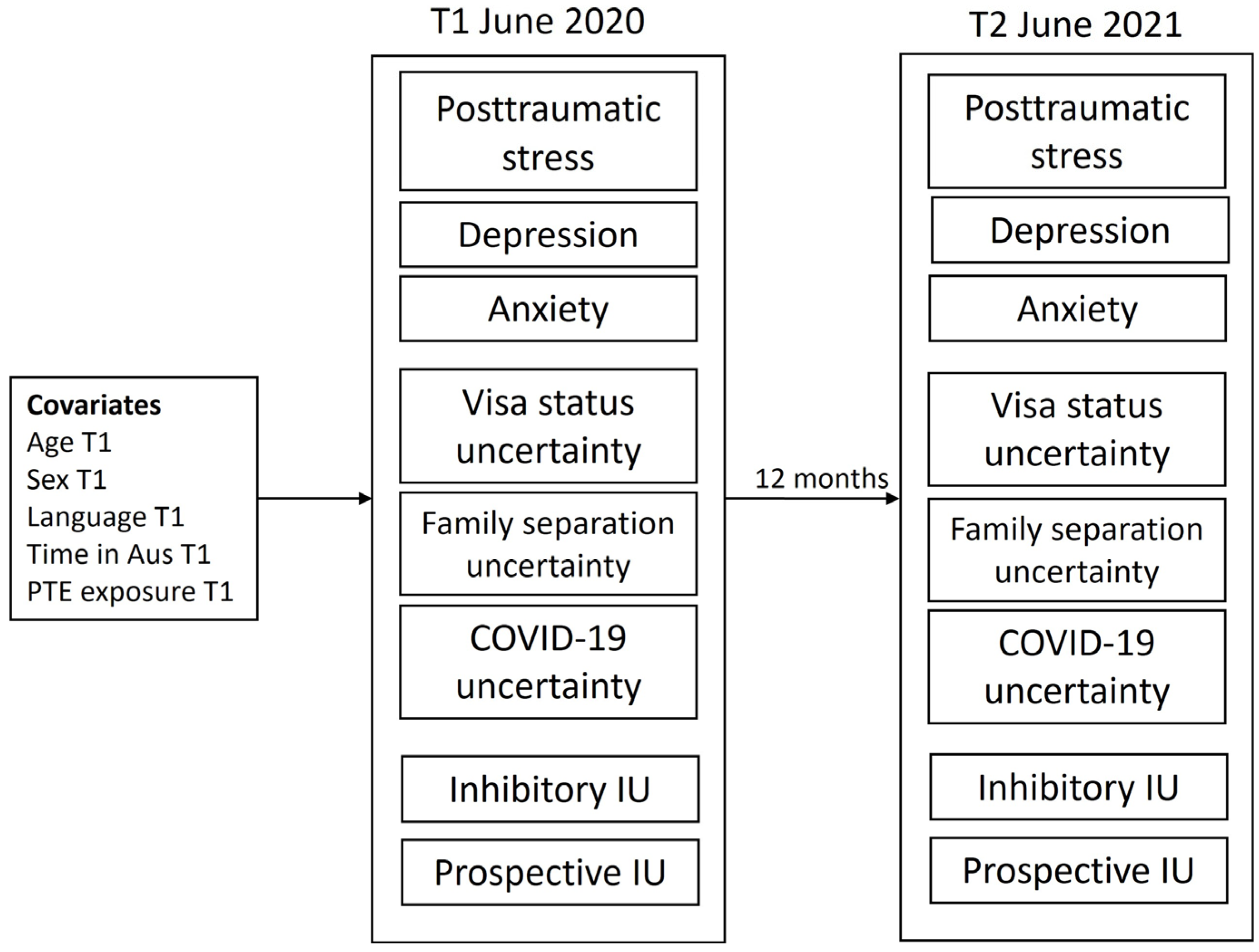

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Measures

2.2.2. Psychological Symptoms Measures

2.2.3. Visa Status, Family Separation, and COVID-19 Stress Measurement

2.2.4. Intolerance of Uncertainty (IU)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

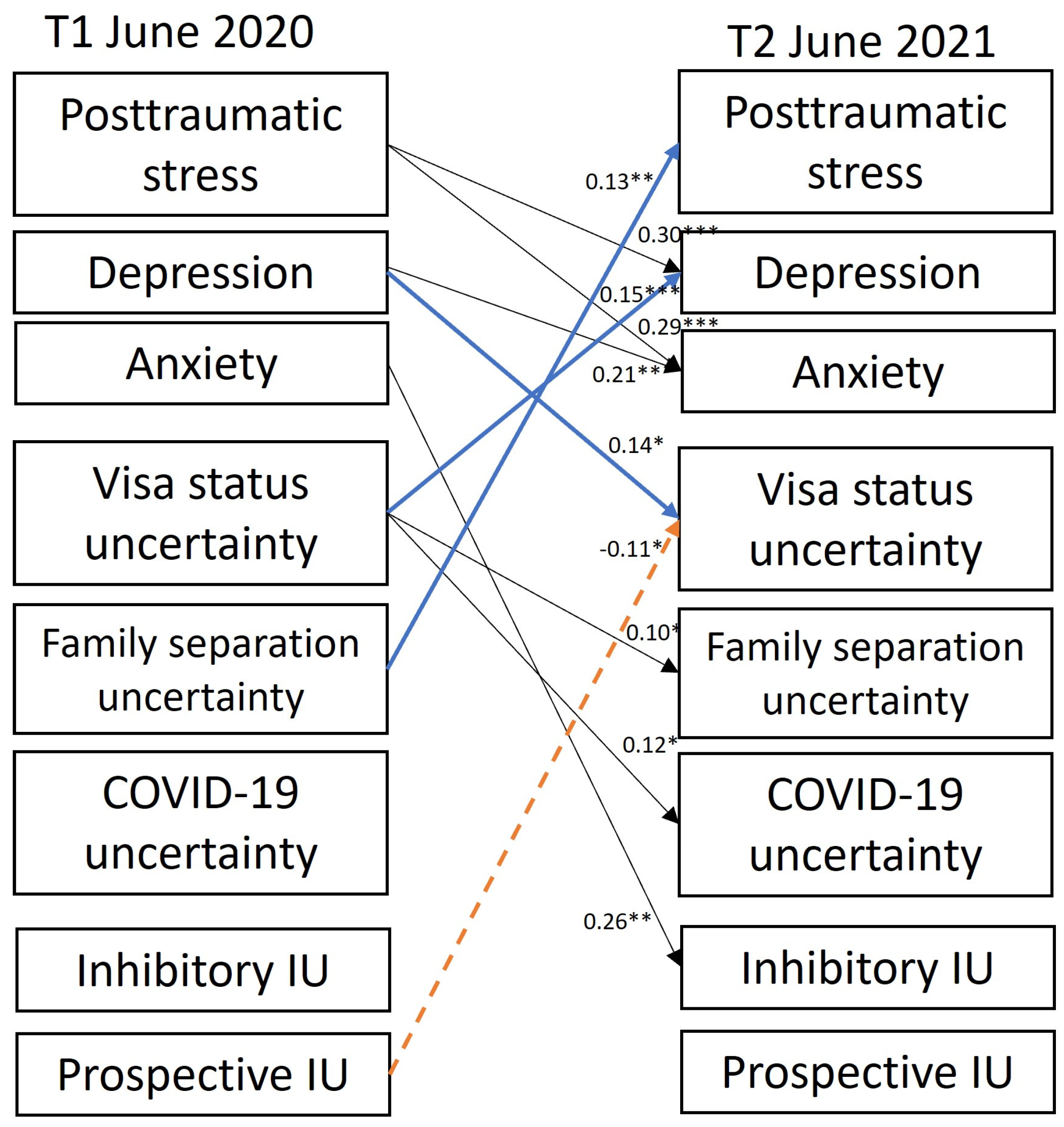

3.2. Cross-Lag Panel Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual |

| GAD | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| IU | Intolerance of uncertainty |

| PTS | Post-traumatic stress |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| T1 | Time 1 |

| T2 | Time 2 |

References

- Steel, Z.; Liddell, B.J.; Bateman Steel, C.; Zwi, A. Global protection and the health impact of migration interception. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T.; Tan, N.F. The end of the deterrence paradigm? Future directions for global refugee policy. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2017, 5, 28–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew and Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law. Research Brief: Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) and Safe Haven Enterprise Visas (SHEVs). 2022. Available online: www.unsw.edu.au/content/dam/pdfs/unsw-adobe-websites/kaldor-centre/2023-09-research-briefs/2023-09-Research-Brief_TPV_SHEV_Aug2018.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Nickerson, A.; Byrow, Y.; O’Donnell, M.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Pajak, R.; Li, S.-L.; Hamilton, A.; Minihan, S.; Liu, C.; et al. The association between visa insecurity and mental health, disability and social engagement in refugees living in Australia. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1688129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Byrow, Y.; O’Donnell, D.A.; Mau, V.; Batch, N.; McMahon, T.; Bryant, R.A.; Nickerson, A. Mechanisms underlying the mental health impact of family separation on resettled refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Byrow, Y.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Hoffman, J.; Mastrogiovanni, N.; Specker, P.; Liddell, B.J. The mental health effects of changing from insecure to secure visas for refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.; Hess, J.M.; Bybee, D.; Goodkind, J.R. Understanding the mental health consequences of family separation for refugees: Implications for policy and practice. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, E.A.; Pearman, A.; Olinga-Shannon, S.; Nickerson, A. The mental health effects of visa insecurity for refugees and people seeking asylum: A latent class analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.; Fisher, J. COVID-19 and the mental health of people from refugee backgrounds. Int. J. Health Serv. 2020, 50, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.G.; de Sales, J.P.; Moreira, M.M.; Pinheiro, W.R.; Lima, C.K.T.; Neto, M.L.R. A crisis within the crisis: The mental health situation of refugees in the world during the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 288, 113000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; O’Donnell, M.L.; Bryant, R.A.; Murphy, S.; Byrow, Y.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Benson, G.; Nickerson, A. The association between COVID-19 related stressors and mental health in refugees living in Australia. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1947564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momartin, S.; Steel, Z.; Coello, M.; Aroche, J.; Silove, D.; Brooks, R. A comparison of the mental health of refugees with temporary versus permanent protection visas. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z.; Silove, D.; Brooks, R.; Momartin, S.; Alzuhairi, B.; Susljik, I. Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 188, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, R.; Wells, R.; Solaimani, J.; Berle, D.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Silove, D.; Nickerson, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R.; McFarlane, A.; et al. The mental health of Farsi-Dari speaking asylum-seeking children and parents facing insecure residency in Australia. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 27, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, Z.; Momartin, S.; Silove, D.; Coello, M.; Aroche, J.; Tay, K.W. Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Steel, Z.; Bryant, R.; Brooks, R.; Silove, D. Change in visa status amongst Mandaean refugees: Relationship to psychological symptoms and living difficulties. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 187, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Bryant, R.A.; Steel, Z.; Silove, D.; Brooks, R. The impact of fear for family on mental health in a resettled Iraqi refugee community. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, R.; Melville, F.; Steel, Z.; Lacherez, P. Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogden, G.; Berle, D.; Steel, Z. The impact of family separation and worry about family on psychological adjustment in refugees resettled in Australia. J. Traumatic Stress 2020, 33, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Malhi, G.S.; Felmingham, K.L.; Den, M.L.; Das, P.; Outhred, T.; Nickerson, A.; Askovic, M.; Coello, M.; Aroche, J.; et al. Activating the attachment system modulates neural responses to threat in refugees with PTSD. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Batch, N.; Hellyer, S.; Bulnes-Diez, M.; Kamte, A.; Klassen, C.; Wong, J.; Byrow, Y.; Nickerson, A. Understanding the effects of being separated from family on refugees in Australia: A qualitative study. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procter, N. The Local-Global Nexus and Mental Health of Transnational Communities; Hawke Institute, University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif-Esfahani, P.; Hoteit, R.; El Morr, C.; Tamim, H. Fear of COVID-19 and depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD among Syrian refugee parents in Canada. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Bawaneh, A.; Awwad, M.; Al-Hayek, H.; Sijbrandij, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Bryant, R.A. A longitudinal study of mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Syrian refugees. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Zihnioglu, O. Effects of COVID-19-related life changes on mental health in Syrian refugees in Turkey. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, J.; Finucane, M.L.; Locker, A.R.; Baird, M.D.; Roth, E.A.; Collins, R.L. A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2021, 143, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Ruhm, C.J.; Puac-Polanco, V.; Hwang, I.H.; Lee, S.; Petukhova, M.V.; Sampson, N.A.; Ziobrowski, H.N.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Zubizarreta, J.R. Estimated prevalence of and factors associated with clinically significant anxiety and depression among US adults during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2217223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettman, C.K.; Abdalla, S.M.; Cohen, G.H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N. Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raines, A.M.; Oglesby, M.E.; Walton, J.L.; True, G.; Franklin, C.L. Intolerance of uncertainty and DSM-5 PTSD symptoms: Associations among a treatment seeking veteran sample. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019, 62, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.; Exline, J.J.; Fletcher, T.L.; Teng, E.J. Intolerance of uncertainty prospectively predicts the transdiagnostic severity of emotional psychopathology: Evidence from a Veteran sample. J. Anxiety Disord. 2022, 86, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Mulvogue, M.K.; Thibodeau, M.A.; McCabe, R.E.; Martin, A.M.; Amsmundson, G.J.G. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.; Steel, Z.; Harb, M.; Mahoney, C.; Berle, D. Changes in intolerance of uncertainty over the course of treatment predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in an inpatient sample. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2022, 29, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelen, P.A. Intolerance of uncertainty predicts analogue posttraumatic stress following adverse life events. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, A.; Hoffman, J.; Keegan, D.; Kashyap, S.; Argadianti, R.; Tricesaria, D.; Pestalozzi, Z.; Nandyatama, R.; Khakbaz, M.; Nilasari, N.; et al. Intolerance of uncertainty, posttraumatic stress, depression, and fears for the future among displaced refugees. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 94, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriss, J.; Zuj, D.V.; Mertens, G. The role of intolerance of uncertainty in classical threat conditioning: Recent developments and directions for future research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2021, 166, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Hoffman, J.; Keegan, D.; Kashyap, S.; Tricesaria, D.; Pestalozzi, Z.; Argadianti Rachmah, R.; Nandyatama, R.; Khakbaz, M.; Nilasari, N.; et al. Context, coping, and mental health in refugees living in protracted displacement. J. Traumatic Stress 2022, 35, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millroth, P.; Frey, R. Fear and anxiety in the face of COVID-19: Negative dispositions towards risk and uncertainty as vulnerability factors. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 83, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A.; Geffen, L.; Koslowsky, M. Life under the COVID-19 lockdown: On the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. Psychol. Traumatic 2021, 13, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R.; Caspi-Yavin, Y.; Bollini, P.; Truong, T.; Tor, S.; Lavelle, J. The harvard trauma questionnaire; validating a cross cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder in Indochina refugees. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1992, 180, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Byrow, Y.; Rasmussen, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R.; Murphy, S.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Benson, G.; Liddell, B. Profiles of exposure to potentially traumatic events in refugees living in Australia. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E. Posttraumatic Diagnostic Manual; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, D.; Steel, Z.; McGorry, P.; Mohan, P. Trauma exposure, postmigration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum-seekers: Comparison with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1998, 97, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z.; Silove, D.; Bird, K.; McGorry, P.; Mohan, P. Pathways from war trauma to posttraumatic stress symptoms among tamil asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants. J. Traumatic Stress 1999, 12, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, M.A.; Asmundson, G.J. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specker, P.; Liddell, B.J.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Byrow, Y.; Nickerson, A. The longitudinal association between posttraumatic stress disorder, emotion dysregulation, and postmigration stressors among refugees. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 12, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus Version 8. 1998–2023. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Procter, N.; Kenny, M.; Eaton, H.; Grech, C. Lethal hopelessness: Understanding and responding to asylum seeker distress and mental deterioration. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddell, B.J.; Das, P.; Malhi, G.S.; Nickerson, A.; Felmingham, K.; Askovic, M.; Aroche, J.; Coello, M.; Cheung, J.; Den, M.; et al. Refugee visa insecurity disrupts the brain’s default mode network. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2213595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali-Naqvi, O.; Alburak, T.A.; Selvan, K.; Abdelmeguid, H.; Malvankar-Mehta, M.S. Exploring the impact of family separation on refugee mental health: A systematic review and meta-narrative Analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2023, 94, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, A.E.; McEvoy, P.M. Trait versus situation-specific intolerance of uncertainty in a clinical sample with anxiety and depressive disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2012, 41, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.F. Exposure to the stressor environment prevents the temporal dissipation of behavioral depression/learned helplessness. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angehrn, A.; Krakauer, R.L.; Carleton, R.N. The impact of intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety sensitivity on mental health among public safety personnel: When the uncertain is unavoidable. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khaz’Aly, H.; Jim, S.; Liew, C.H.; Zamudio, G.; Jin, L. Relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and mental wellness: A cross-cultural examination. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2023, 37, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Batch, N.; Bulnez-Diez, M.; Hellyer, S.; Kamte, A.; Wong, J.; Byrow, Y.; Nickerson, A. The Effects of Family Separation on Forcibly Displaced People in Australia: Findings from a Pilot Research Project; Australian Red Cross and UNSW Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.E.; Rasmussen, A. The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: An ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunn, M.; Khanna, D.; Farmer, E.; Esbrook, E.; Ellis, H.; Richard, A.; Weine, S. Rethinking mental healthcare for refugees. SSM Ment. Health 2023, 3, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baganz, E.; McMahon, T.; Khorana, S.; Magee, L.; Culos, I. ‘Life would have been harder, harder and more in chaos, if there wasn’t internet’: Digital inclusion among newly arrived refugees in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun. Res. Pract. 2024, 11, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.F.A.; Hess, J.M.; Goodkind, J.R. Family Separation and the Impact of Digital Technology on the Mental Health of Refugee Families in the United States: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, A. Refugee integration and social media: A local and experiential perspective. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 21, 1588–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurs, K. Communication rights from the margins: Politicising young refugees’ smartphone pocket archives. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2017, 79, 674–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A. Scalable interventions for refugees. Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Byrow, Y.; O’Donnell, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Benson, G.; Liddell, B.J. Cognitive mechanisms underlying the association between trauma exposure, mental health and social engagement in refugees: A longitudinal investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 307, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Timepoint 1 (T1) June 2020 N = 656 | Timepoint 2 (T2) June 2021 N = 560 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | ||

| Age (years) | 42.83 | 12.32 | 43.68 | 12.53 | |

| Sex | Male | 333 | 50.8% | 278 | 49.6% |

| Female | 323 | 49.2% | 282 | 50.4% | |

| Language | Arabic | 514 | 78.4% | 411 | 73.4% |

| Farsi | 65 | 9.9% | 45 | 8.0% | |

| English | 59 | 9.0% | 48 | 8.6% | |

| Tamil | 18 | 2.7% | 56 | 10% | |

| Country of origin | Iraq | 406 | 61.9% | 356 | 63.6% |

| Syria | 118 | 18.0% | 82 | 14.6% | |

| Iran | 67 | 10.2% | 62 | 11.1% | |

| Sri Lanka | 20 | 3.0% | 23 | 4.1% | |

| Afghanistan | 10 | 1.5% | 10 | 1.8% | |

| Other | 35 | 5.3% | 27 | 4.8% | |

| Marital status | Married/partnered | 503 | 76.7% | 424 | 75.7% |

| Widow/widower | 17 | 2.6% | 19 | 3.4% | |

| Divorced/separated | 21 | 3.2% | 20 | 3.6% | |

| Single/never married | 113 | 17.2% | 95 | 17.0% | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Visa status | Secure visa | 541 | 82.5% | 451 | 80.5% |

| Insecure visa | 110 | 16.8% | 102 | 18.2% | |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.8% | 6 | 1.1% | |

| Time in Australia (years) | 4.60 | 3.81 | 5.71 | 1.71 | |

| PTE exposure (experienced/witnessed) | 3.88 | 4.08 | - | - | |

| Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PDS; DSM-5); mean | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.66 | |

| Depression symptoms (PHQ-9); mean | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.74 | |

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7); mean | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.76 | |

| Visa status uncertainty stressors; mean | 1.59 | 1.09 | 1.65 | 1.13 | |

| Family separation uncertainty stressors; mean | 2.36 | 1.25 | 2.44 | 1.28 | |

| COVID-19 uncertainty stressors; mean | 2.05 | 0.78 | 2.05 | 0.83 | |

| Inhibitory IU; mean | 2.54 | 0.87 | 2.44 | 0.91 | |

| Prospective IU; mean | 2.80 | 0.77 | 2.71 | 0.84 | |

| B (s.e) | β | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoregressive Paths | |||||

| T1 PTSD symptoms → | T2 PTSD symptoms | 0.62 (0.06) | 0.69 | 10.06 | <0.001 |

| T1 depression symptoms → | T2 depression symptoms | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.39 | 6.02 | <0.001 |

| T1 anxiety symptoms → | T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.29 | 4.22 | <0.001 |

| T1 visa uncertainty → | T2 visa uncertainty | 0.78 (0.04) | 0.77 | 21.39 | <0.001 |

| T1 family separation uncertainty → | T2 family separation uncertainty | 0.67 (0.04) | 0.69 | 15.75 | <0.001 |

| T1 COVID-19 uncertainty → | T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | 0.54 (0.05) | 0.53 | 10.26 | <0.001 |

| T1 inhibitory IU → | T2 inhibitory IU | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.30 | 4.60 | <0.001 |

| T1 prospective IU → | T2 prospective IU | 0.34 (0.07) | 0.32 | 5.18 | <0.001 |

| Cross-lagged paths | |||||

| T1 PTSD symptoms → | T2 depression symptoms | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.30 | 4.68 | <0.001 |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.30 (0.07) | 0.29 | 4.27 | <0.001 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.844 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | −0.09 (0.12) | −0.05 | −0.77 | 0.442 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.597 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.667 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.08 | 0.91 | 0.363 | |

| T1 depression symptoms → | T2 PTSD symptoms | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.01 | 1.37 | 0.172 |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.21 (0.07) | 0.21 | 3.03 | 0.002 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.14 | 2.25 | 0.025 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | 0.16 (0.12) | 0.09 | 1.33 | 0.183 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.12 | 1.40 | 0.162 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | 0.09 (0.12) | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.389 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.04 (0.10) | 0.04 | 0.432 | 0.665 | |

| T1 anxiety symptoms → | T2 PTSD symptoms | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.05 | −0.65 | 0.518 |

| T2 depression symptoms | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.482 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | −0.04 (0.10) | −0.03 | −0.40 | 0.688 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | 0.07 (0.11) | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.527 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.957 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | 0.31 (0.10) | 0.26 | 3.01 | 0.003 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.18 (0.10) | 0.16 | 1.83 | 0.068 | |

| T1 visa uncertainty → | T2 PTSD symptoms | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.03 | −0.82 | 0.414 |

| T2 depression symptoms | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.15 | 3.97 | <0.001 | |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.05 | 1.17 | 0.243 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.10 | 2.40 | 0.016 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.12 | 2.56 | 0.010 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.328 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.624 | |

| T1 family separation uncertainty → | T2 PTSD symptoms | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.13 | 2.76 | 0.006 |

| T2 depression symptoms | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.07 | 1.53 | 0.126 | |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.002 (0.03) | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.952 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 | −0.20 | 0.844 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.01 | −0.24 | 0.810 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.07 | −1.15 | 0.251 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.569 | |

| T1 COVID-19 uncertainty → | T2 PTSD symptoms | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.04 | −0.75 | 0.454 |

| T2 depression symptoms | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.05 | −1.13 | 0.258 | |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.06 | −1.23 | 0.217 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 | 0.123 | 0.902 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | −0.06 (0.07) | −0.04 | −0.86 | 0.392 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.08 | −1.31 | 0.189 | |

| T2 prospective IU | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.04 | −0.76 | 0.448 | |

| T1 inhibitory IU → | T2 PTSD symptoms | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 | 0.78 | 0.438 |

| T2 depression symptoms | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.07 | 1.31 | 0.191 | |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 | 1.19 | 0.232 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.647 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | 0.03 (0.08) | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.680 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.01 | −0.15 | 0.880 | |

| T2 prospective IU | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.404 | |

| T1 prospective IU → | T2 PTSD symptoms | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.08 | −1.68 | 0.093 |

| T2 depression symptoms | −0.07(0.04) | −0.08 | −1.64 | 0.100 | |

| T2 anxiety symptoms | −0.002 (0.05) | −0.002 | −0.04 | 0.966 | |

| T2 visa uncertainty | −0.16 (0.07) | −0.11 | −2.52 | 0.012 | |

| T2 family separation uncertainty | −0.05 (0.07) | −0.03 | −0.69 | 0.490 | |

| T2 COVID-19 uncertainty | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.02 | −0.40 | 0.690 | |

| T2 inhibitory IU | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.08 | 1.27 | 0.205 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liddell, B.J.; Murphy, S.; Byrow, Y.; O’Donnell, M.; Mau, V.; McMahon, T.; Bryant, R.A.; Specker, P.; Nickerson, A. Longitudinal Associations Between Sources of Uncertainty and Mental Health Amongst Resettled Refugees During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060855

Liddell BJ, Murphy S, Byrow Y, O’Donnell M, Mau V, McMahon T, Bryant RA, Specker P, Nickerson A. Longitudinal Associations Between Sources of Uncertainty and Mental Health Amongst Resettled Refugees During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060855

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiddell, Belinda J., Stephanie Murphy, Yulisha Byrow, Meaghan O’Donnell, Vicki Mau, Tadgh McMahon, Richard A. Bryant, Philippa Specker, and Angela Nickerson. 2025. "Longitudinal Associations Between Sources of Uncertainty and Mental Health Amongst Resettled Refugees During the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060855

APA StyleLiddell, B. J., Murphy, S., Byrow, Y., O’Donnell, M., Mau, V., McMahon, T., Bryant, R. A., Specker, P., & Nickerson, A. (2025). Longitudinal Associations Between Sources of Uncertainty and Mental Health Amongst Resettled Refugees During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060855