Manifestation and Markings of HIV Stigma in Indonesia: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

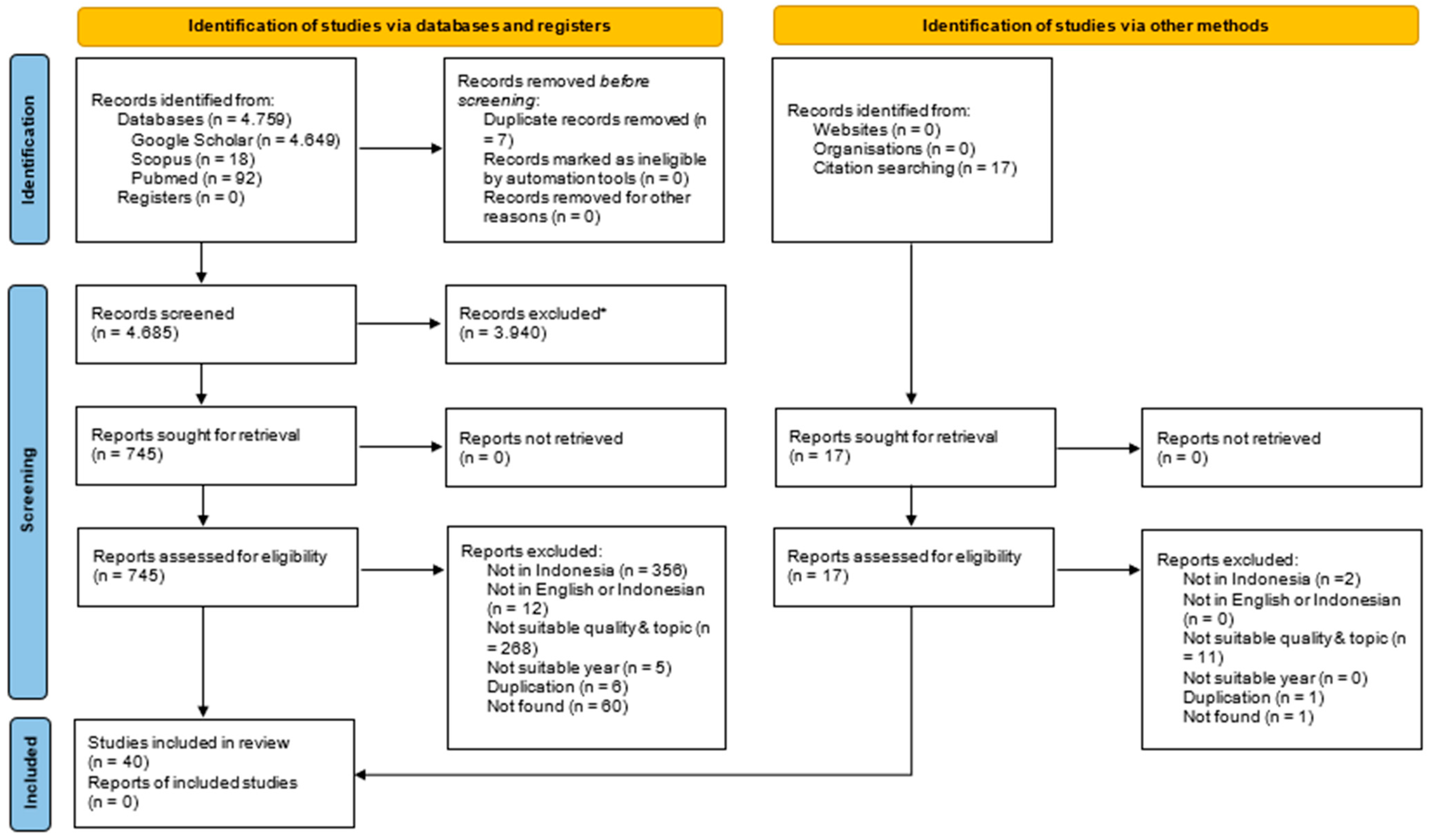

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.1.1. Electronic Databases

2.1.2. Reference List Searches

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Published or conducted between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2023: This criterion was applied to ensure that the data were relevant to the current situation of HIV stigma.

- Written in English: This was performed to enhance the accessibility of the literature for global academic analysis.

- Conducted in Indonesia: This criterion was used to obtain data specific to the context of HIV stigma in Indonesia.

- Contained findings related to the manifestations or forms of HIV stigma in Indonesia, such as the type of stigma that emerged in specific contexts, the level or intensity of stigma in particular settings, and certain characteristics of PLHIV and key populations that were perceived as different by those enacting the stigma, thereby triggering its occurrence. This criterion was used to ensure that the reviewed literature was directly relevant to the main objectives of the review.

- Not review research: Only primary research studies and those using secondary data sources were included, excluding the literature review.

2.3. Literature Selection

2.3.1. Abstract and Title Screening

2.3.2. Full-Article Screening

2.4. Data Charting

2.5. Data Items

2.6. Synthesis Result Method

3. Results

3.1. The Situation of HIV-Related Stigma in Indonesia

3.2. The Manifestations of HIV-Related Stigma in Indonesia

3.2.1. Avoiding Contact with PLHIV as a Common Manifestation of HIV-Related Stigma

3.2.2. Different Treatment by Those Willing to Interact with PLHIV

3.2.3. Negative Social Reactions to PLHIV

3.2.4. Self-Stigma

3.2.5. HIV Stigma Among Children, Adolescents, Pregnant Women, and Key Populations

3.2.6. Gradual Changes in HIV-Related Stigma Within Communities

3.3. The Markings of HIV-Related Stigma in Indonesia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemenkes, R.I. Laporan Eksekutif Perkembangan HIV AIDS dan Penyakit Menular Seksual (PIMS) Triwulan I Tahun 2022. 2023. Available online: https://hivaids-pimsindonesia.or.id/download/file/LaporanTW_I_2023.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Marcus, J.L.; Chao, C.R.; Leyden, W.A.; Xu, L.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Klein, D.B.; Towner, W.J.; Horberg, M.A.; Silverberg, M.J. Narrowing the Gap in Life Expectancy between HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Individuals with Access to Care. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 73, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trickey, A.; May, M.T.; Vehreschild, J.J.; Obel, N.; Gill, M.J.; Crane, H.M.; Boesecke, C.; Patterson, S.; Grabar, S.; Cazanave, C.; et al. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: A collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, e349–e356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Cescon, A.; Hogg, R.S.; Modur, S.P.; Althoff, K.N.; Buchacz, K.; Burchell, A.N.; Cohen, M.; Gebo, K.A.; Gill, M.J.; et al. Closing the gap: Increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, S.; Agung, A.; Sawitri, S.; Putu, L.; Wulandari, L.; Gede, I.; Eka, A.; Ayu, P.; Astuti, S.; Wirawan, D.N.; et al. Mortality among people living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment in Bali, Indonesia: Incidence and predictors. Int. J. STD AIDS 2017, 28, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direktorat Jenderal Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Penyakit Kementerian Kesehatan RI. Laporan Tahunan HIV AIDS 2022. 2023. Available online: https://hivaids-pimsindonesia.or.id/download?kategori=Laporan%20Triwulan (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Irmayati, N.; Yona, S.; Waluyo, A. HIV-related Stigma, Knowledge about HIV, HIV Risk Behavior and HIV Testing Motivation among Women in Lampung, Indonesia. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmah; Andajani, S.; Davies, S.G. Perceptions of and barriers to HIV testing of women in Indonesia. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1848003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutahaean, B.S.H.; Stutterheim, S.E.; Jonas, K.J. Barriers and Facilitators to HIV Treatment Adherence in Indonesia: Perspectives of People Living with HIV and HIV Service Providers. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, K.N.; Hanifah, L.; Rikawarastuti; Wahyuniar, L. Prevention of HIV Transmission from Mother to Child: Challenges to the Successful Program Implementation and Practice in Indonesia. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2021, 20, 23259582211040701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Latifah, E.; Probandari, A.; Effendy, C.; Taxis, K. Daily struggle to take antiretrovirals: A qualitative study in Papuans living with HIV and their healthcare providers. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma; Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Stigma and Discrimination. cdc.gov. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240101014938/https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- UNAIDS. Hiv and Stigma and Discrimination Human Rights Fact Sheet Series 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/07-hiv-human-rights-factsheet-stigma-discrmination (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Babel, R.A.; Wang, P.; Alessi, E.J.; Raymond, H.F.; Wei, C. Stigma, HIV Risk, and Access to HIV Prevention and Treatment Services Among Men Who have Sex with Men (MSM) in the United States: A Scoping Review. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3574–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, K. ‘If I Don’t Take My Treatment, I Will Die and Who Will Take Care of My Child?’: An Investigation into an Inclusive Community-led Approach to Addressing the Barriers to HIV Treatment Adherence by Postpartum Women Living with HIV. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0271294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iott, B.E.; Loveluck, J.; Benton, A.; Golson, L.; Kahle, E.; Lam, J.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Veinot, T.C. The Impact of Stigma on HIV Testing Decisions for Gay, Bisexual, Queer and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.K.; Vu, B.N.; Susa, J.; DeSilva, M. Stigma, Coping Strategies, and Their Impact on Treatment and Health Outcomes Among Young Men Living with HIV in Vietnam: A Qualitative Study. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Perwitasari, D.A.; Islam, M.A.; Taxis, K. The association between ethnicity, stigma, beliefs about medicines and adherence in people living with HIV in a rural area in Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardojo, S.S.I.; Huang, Y.L.; Chuang, K.Y. Determinants of the Quality of Life amongst HIV Clinic Attendees in Malang, Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; Van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barré, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A Global, Crosscutting Framework to Inform Research, Intervention Development, and Policy on Health-Related Stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards A Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.E.; Endres-dighe, S.; Sucaldito, A.D.; Piscalko, H.; Kiriazova, T.; Batchelder, A.W. Measuring and Addressing Stigma Within HIV Interventions for People Who Use Drugs: A Scoping Review of Recent Research. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023, 19, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulawa, M.I.; Rosengren, A.L.; Amico, K.R.; Hightow-Weidman, L.B.; Muessig, K.E. MHealth to Reduce HIV-related Stigma among Youth in the United States: A Scoping Review. mHealth 2021, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geter, A.; Herron, A.R.; Sutton, M.Y. HIV-Related Stigma by Healthcare Providers in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018, 32, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D. Download Publish or Perish. harzing.com, 2024, p. 1. Available online: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish/windows (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for The Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursalam, N.; Sukartini, T.; Kuswanto, H.; Setyowati, S.; Mediarti, D.; Rosnani, R.; Pradipta, R.O.; Ubudiyah, M.; Mafula, D.; Klankhajhon, S.; et al. Investigation of Discriminatory Attitude toward People Living with HIV in the Family Context using Socio-economic Factors and Information Sources: A Nationwide Study in Indonesia. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadarang, R.A.I. Prevalence and Factors Affecting Discrimination Towards People Living with HIV/AIDS in Indonesia. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2022, 55, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Busthomy Rofi’I, A.Y.; Kurnia, A.D.; Bahrudin, M.; Waluyo, A.; Purwanto, H. Determinant Factors Correlated with Discriminatory Attitude towards People Living with HIV in Indonesian Population: Demographic and Health Survey Analysis. HIV AIDS Rev. 2023, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursalam, N.; Sukartini, T.; Arifin, H.; Pradipta, R.O.; Mafula, D.; Ubudiyah, M. Determinants of the Discriminatory Behavior Experienced by People Living with HIV in Indonesia: A Cross-sectional Study of the Demographic Health Survey. Open AIDS J. 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, H.; Ibrahim, K.; Rahayuwati, L.; Herliani, Y.K.; Kurniawati, Y.; Pradipta, R.O.; Sari, G.M.; Ko, N.Y.; Wiratama, B.S. HIV-related Knowledge, Information, and Their Contribution to Stigmatization Attitudes among Females Aged 15–24 Years: Regional Disparities in Indonesia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, G.B.S.; Gustina, N.L.Z.; Januraga, P.P. Open Communication about Reproductive Health Is Associated with Comprehensive HIV Knowledge and a Non-stigmatising Attitude among Indonesian Youth: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2022, 55, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Latifah, E.; Pane, M.; Perwitasari, D.A.; Satibi; Kristina, S.A.; Hastuti, E.B.; Pavlovich, J.; Taxis, K. Knowledge, empathy, and willingness to counsel patients with HIV among Indonesian pharmacists: A national survey of stigma. AIDS Care—Psychol. Socio-Medical Asp. AIDS/HIV 2022, 34, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, M.T.P.L.; Kidd, T.; Muturi, N.; Procter, S.B.; Yarrow, L.; Hsu, W.W. HIV Knowledge and Stigma among Dietetic Students in Indonesia: Implications for the Nutrition Education System. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluyo, A.; Mansyur, M.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Steffen, A.; Herawati, T.; Maria, R.; Culbert, G.J. Exploring HIV stigma among future healthcare providers in Indonesia. AIDS Care—Psychol. Socio-Medical Asp. AIDS/HIV 2022, 34, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langi, G.G.; Rahadi, A.; Praptoraharjo, I.; Ahmad, R.A. HIV-related Stigma and Discrimination Among Health Care Workers During Early Program Decentralization in Rural District Gunungkidul, Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafisah, L.; Riono, P.; Muhaimin, T. Do Stigma and Disclosure of HIV Status are Associated with Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among Men who Have Sex with Men? HIV AIDS Rev. 2021, 19, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovari, I.; Anggreini, S.N.; Wahyuni, F.; Novita, R. Knowledge and reliance on the availability of voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) services relating to the utilization of VCT services by the Man who has Sex with Man community. Gac. Med. Caracas 2022, 130 (Suppl. S5), S990–S996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya, N.A.J.; Nilmanat, K. Experience and management of stigma among persons living with HIV in Bali, Indonesia: A descriptive study. Japan J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 18, e12391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Simbayi, L.C.; Jooste, S.; Toefy, Y.; Cain, D.; Cherry, C.; Kagee, A. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2005, 9, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Ward, P.R.; Hawke, K.; Mwanri, L. HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Perspectives and Personal Experiences of Healthcare Providers in Yogyakarta and Belu, Indonesia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 625787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, L.P.L.; Ruddick, A.; Guy, R.; Kaldor, J. ‘Self-testing sounds more private, rather than going to the clinic and everybody will find out’: Facilitators and barriers regarding HIV testing among men who purchase sex in Bali, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, T.; Jannah, S.R.; Asniar; Tahlil, T.; Susanti, S.S. Stigma experienced by women living with HIV/AIDS in Aceh province: A phenomenological study. Enferm. Clin. 2022, 32, S62–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Gesesew, H.A.; Mwanri, L.; Hawke, K.; Ward, P.R. HIV-related challenges and women’s self-response: A qualitative study with women living with HIV in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes, Y.L.N.; Songwathana, P. Understanding Stigma and Coping Strategies among HIV-negative Muslim Wives in Serodiscordant Relationships in a Javanese Community, Indonesia. Belitung Nurs. J. 2021, 7, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamboro, D.B.; Fauk, N.K.; Ward, P.R.; Merry, M.S.; Siri, T.A.; Mwanri, L. HIV stigma and moral judgement: Qualitative exploration of the experiences of HIV stigma and discrimination among married men living with HIV in Yogyakarta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauk, N.K.; Hawke, K.; Mwanri, L.; Ward, P.R. Stigma and Discrimination towards People Living with HIV in the Context of Families, Communities, and Healthcare Settings: A Qualitative Study in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrina, A.; Ikhtiar, M.; Idris, F.P.; Adam, A.; Alim, A. Community Stigma and Discrimination against the Incidence of HIV and AIDS. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinulingga, E.; Waluyo, A. The Role of the Church Members and Nurses in Improving Self-awareness to Prevent HIV. J. Public health Res. 2021, 10, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.S.; Susanti, H.; Mustikasari, M.; Khoirunnisa, K.; Fitriani, N.; Yosep, I.; Widianti, E.; Ibrahim, K.; Komariah, M.; Maulana, S.; et al. Qualitative Exploration of Experiences and Consequences of Health-related Stigma among Indonesians with HIV, Leprosy, Schizophrenia and Diabetes. Kesmas 2020, 15, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, K.; Swandari, P.; Rahma, G.; Parwati Merati, T.; Bakta, I.M.; Pradnyaparamita Duarsa, D. Nursing Care on HIV/AIDS-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Descriptive Study of Nurse’s Perspective in Indonesia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camellia, A.; Swandari, P.; Rahma, G.; Merati, T.P.; Bakta, I.M.; Duarsa, D.P. A peer-support mini-counseling model to improve treatment in hiv-positive pregnant women in kupang city, east nusa tenggara, Indonesia. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 56, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Herliani, Y.K.; Rahayuwati, L.; Khadijah, S.; Sutini, T. Healthcare needs of people living with human immunodeficiency virus: A qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianturi, E.I.; Latifah, E.; Gunawan, E.; Sihombing, R.B.; Parut, A.A.; Perwitasari, D.A. Adaptive Stigma Coping Among Papuans Living with HIV: A Qualitative Study in One of the Indigenous People, Indonesia. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Merry, M.S.; Mwanri, L.; Hawke, K.; Ward, P.R. Mental Health Challenges and the Associated Factors in Women Living with HIV Who Have Children Living with HIV in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najmah; Davies, S.G.; Kusnan, K.; Davies, T.G. ‘It’s Better to Treat a COVID Patient than a HIV Patient’: Using Feminist Participatory Research to Assess Women’s Challenges to Access HIV Care in Indonesia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ther. Adv. Vaccines 2021, 8, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuardi, E.; Yusuf, A.; Makhfudli; Harianto, S.; Okviasanti, F.; Kartini, Y. Increasing HIV treatment access, uptake and use among men who have sex with men in urban Indonesia: Evidence from a qualitative study in three cities. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Yusuf, A.; Makhfudli; Harianto, S.; Okviasanti, F.; Kartini, Y. Living experiences of people living with HIVAIDS from the client’s perspective in nurseclient interaction in Indonesia: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulung, N.; Asyura, R. The Analysis of Spirituality of Patients with HIV/AIDS in Taking Lessons and Self-acceptance. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2019, 25, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qur’aniati, N.; Sweet, L.; De Bellis, A.; Hutton, A. Diagnosis, disclosure and stigma: The perspectives of Indonesian children with HIV and their families. J. Child Health Care 2022, 28, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, L.G.; Erasmus, V.; Krier, S.E.; Reviagana, K.P.; Laksmono, P.A.; Widihastuti, A.; Richardus, J.H. Alarmingly High HIV Prevalence Among Adolescent and Young Men Who have Sex with Men (MSM) in Urban Indonesia. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3687–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugroho, A.; Erasmus, V.; E Krier, S.; Reviagana, K.P.; A Laksmono, P.; Widihastuti, A.; Richardus, J.H. Client perspectives on an outreach approach for HIV prevention targeting Indonesian MSM and transwomen. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Direktorat Jenderal Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Penyakit. Laporan Perkembangan HIV AIDS & Penyakit lnfeksi Menular Seksual (PIMS) Triwulan I Tahun 2021; Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Direktorat Jenderal Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Penyakit: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021.

- Valdivieso, P.A.; Alecchi, B.A.; Arévalo-Avecillas, D. Factors that Influence the Individual Research Output of University Professors: The Case of Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia. J. Hispanic High. Educ. 2021, 21, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, S. What Drive Publication Productivity in German Business Faculties? Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2015, 67, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayol, N.; Matt, M. Individual and collective determinants of academic scientists’ productivity. Inf. Econ. Policy 2006, 18, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Network of People Living with HIV. People Living with HIV Stigma Index 2.0: Global Report 2023; Global Network of People Living with HIV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, S.; Hardy, N.; Hogan, J.; DeLong, A.; Kyaw, A.; Tun, M.S.; Aung, K.W.; Kantor, R. Characterization of HIV-Related Stigma in Myanmar. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 2751–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, K.B.; Turan, B.; Whitfield, S.; Kay, E.S.; Budhwani, H.; Fifolt, M.; Hauenstein, K.; Ladner, M.D.; Sewell, J.; Payne-Foster, P.; et al. Patient and Provider Perspectives on HIV Stigma in Healthcare Settings in Underserved Areas of the US South: A Mixed Methods Study. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26 (Suppl. S1), 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Treatment as Prevention. cdc.gov. 2023. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20240101155125/https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- WHO. Patient Safety Rights Charter; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat, J.; Chen, M.Y.; Maulina, R.; Nurbaya, S. Factors Associated with HIV-Related Stigma Among Indonesian Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 31, E295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.; Scott, J.; Ball, M.; Minichiello, V. Deploying Nationalist Discourses to Reduce Sex-, gender and HIV-related Stigma in Thailand. Biosocieties 2022, 17, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2024; CHS: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023; pp. 1–120. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2021-coding-guidelines-updated-12162020.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 27 Tahun 2017 Tentang Pedoman Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Infeksi di Fasilitas Pelayanan Kesehatan; Kementerian Kesehatan RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017.

| Category | Sub-Category | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | 2019 | 4 (10%) |

| 2020 | 7 (18%) | |

| 2021 | 11 (28%) | |

| 2022 | 13 (32%) | |

| 2023 | 5 (12%) | |

| Research Method | Qualitative | 25 (63%) |

| Quantitative | 15 (37%) | |

| Data Source Type | Primary | 34 (85%) |

| Secondary | 6 (15%) | |

| Research Locations 1 | Ten provinces with the most PLHIV on ARV | 16 (40%) |

| Other provinces | 15 (38%) | |

| General Indonesia | 9 (23%) | |

| Detail 10 provinces with the most PLHIV on ARV 1 | DKI Jakarta | 5 (12%) |

| East Java | 2 (5%) | |

| West Java | 5 (12%) | |

| Central Java | 0 (0%) | |

| Bali | 3 (7%) | |

| Papua | 3 (7%) | |

| North Sumatera | 1 (2%) | |

| South Sumatera | 2 (5%) | |

| Banten | 1 (2%) | |

| Riau Island | 0 (0%) | |

| Study population 2 | PLHIV | 20 (50%) |

| Key population | 5 (13%) | |

| at-risk population | 4 (10%) | |

| Students | 3 (8%) | |

| General community | 7 (18%) | |

| Healthcare workers | 8 (20%) | |

| Other | 2 (5%) | |

| Findings 3 | Manifestation | 30 (75%) |

| Marking | 11 (27%) | |

| Stigma score instrument | The AIDS-related stigma scale | 1 (3%) |

| Developed questionnaire | 1 (3%) | |

| Nursing’ attitudes AIDS scale | 1 (3%) | |

| No stigma score | 37 (91%) | |

| N = 40 | ||

| Stigma Setting | Family | Comunnity | Healthcare Workers | Workplace Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of stigma manifestations | ||||

| Avoiding contact | ||||

| Different treatment | ||||

| Negative social reactions | ||||

| Types of stigma markings | ||||

| Bad/dirty/immoral person | Not found | |||

| Dangerous person | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sudastri, N.K.; Wulandari, L.P.L.; Januraga, P.P. Manifestation and Markings of HIV Stigma in Indonesia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060840

Sudastri NK, Wulandari LPL, Januraga PP. Manifestation and Markings of HIV Stigma in Indonesia: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060840

Chicago/Turabian StyleSudastri, Ni Kadek, Luh Putu Lila Wulandari, and Pande Putu Januraga. 2025. "Manifestation and Markings of HIV Stigma in Indonesia: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060840

APA StyleSudastri, N. K., Wulandari, L. P. L., & Januraga, P. P. (2025). Manifestation and Markings of HIV Stigma in Indonesia: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060840