Mental Health in Construction Industry: A Global Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

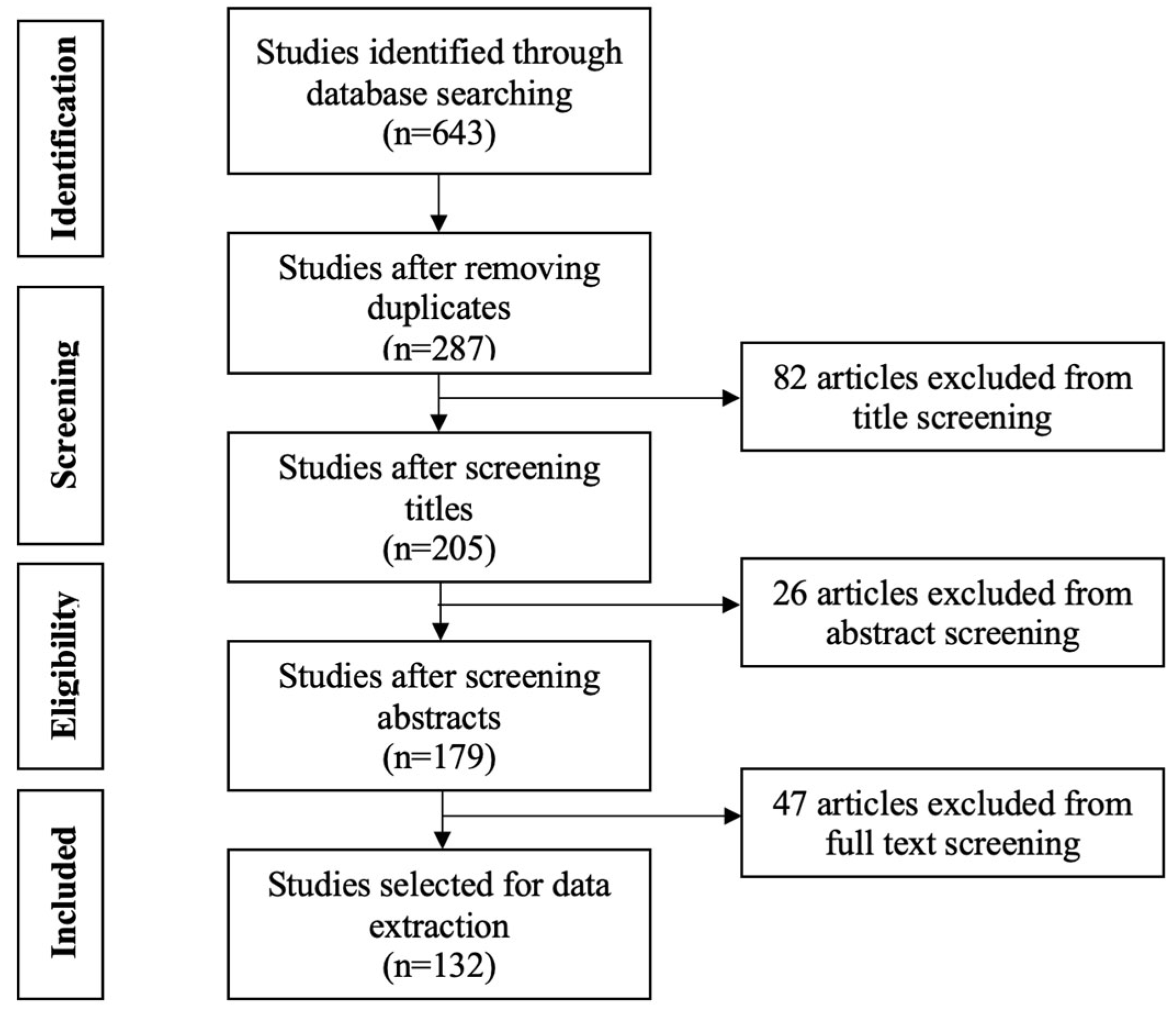

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identifying and Classifying the Risk Factors That Affect the Mental Health of Construction Workforce

3.1.1. Diversity and Equity Risk Factors (DR)

| ID | Risk Factor | Description | Source | Frequency | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR1 | Gender inequality | Men have more opportunities for advancement and are treated more fairly than women. | [21,22] | 29 | 1 |

| DR2 | Sexual Harassment | Female workers experience many types of harassment, including sexual, verbal, and physical assault. | [23,24] | 25 | 2 |

| DR3 | Limited job opportunities for women | Limited job opportunities hinder career growth for female construction workers. | [22,28] | 22 | 3 |

| DR4 | Language barriers | Language barriers prevent effective communication with supervisors and colleagues. | [26,27] | 15 | 4 |

| DR5 | Racial discrimination | Racial discrimination is prevalent on construction sites. | [5,16] | 9 | 5 |

| DR6 | Age discrimination | Younger workers face significant challenges in construction workplaces. | [2,29] | 5 | 6 |

| DR7 | Cultural value conflicts | Conflicts arise from differences in cultural values. | [1,26] | 2 | 7 |

3.1.2. Health-Related Risk Factors (HR)

| ID | Risk Factor | Description | Source | Frequency | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR1 | Poor working environment | Environments that are not ergonomically designed, lack adequate lighting, are not clean, or have other physical deficiencies | [2,5] | 24 | 1 |

| HR2 | Ill-fitting PPE | PPE that does not fit properly and has the potential to cause discomfort, physical strain, and injury | [25,28] | 21 | 2 |

| HR3 | Occupational injuries | Injuries that occur as a direct result of job-related activities, including accidents, falls, cuts, and other physical harm | [30,32] | 18 | 3 |

| HR4 | Musculoskeletal pain | Muscle, nerve, tendon, joint, or spinal disc injuries or pain caused by repetitive strain or overuse | [33,34] | 11 | 4 |

| HR5 | Personal traumas | Emotional or psychological injuries resulting from accidents, violence, or loss, which affect an individual’s mental health | [8,35] | 5 | 5 |

| HR6 | Poor medical services | Lack of adequate medical services | [5,29] | 2 | 6 |

3.1.3. Job-Demand Risk Factors (JR)

3.1.4. Organizational Risk Factors (OR)

| ID | Risk Factor | Description | Source | Frequency | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR1 | Poor work-life balance | An excessive amount of time and effort is devoted to professional responsibilities at the expense of personal commitments | [47,48] | 41 | 1 |

| OR2 | Low job control | Lack of decision-making opportunities | [20,33] | 33 | 2 |

| OR3 | Lack of environment that promotes career development | Environment that lacks opportunities and/or support for career development and promotions | [29,50] | 27 | 3 |

| OR4 | Low job support | Lack of sufficient support from supervisors and colleagues | [30,52] | 25 | 4 |

| OR5 | Procedural prejudice | Inequitable decision-making processes | [36,54] | 19 | 5 |

| OR6 | Lack of recognition | Inadequate rewards or recognition of employee accomplishments | [55,56] | 14 | 6 |

| OR7 | Job insecurity | Lack of job stability | [41,49] | 11 | 7 |

| OR8 | Inadequate freedom of expression | Limited opportunities to express thoughts, opinions, or ideas freely and openly | [50,57] | 7 | 8 |

| OR9 | Lack of training | Lack of job training | [17,25] | 4 | 9 |

| OR10 | Lack of feedback | Lack of feedback on improving performance | [11,58] | 3 | 10 |

| OR11 | Poor communication | Lack of or unclear communication among project teams | [40,59] | 2 | 11 |

| OR12 | Lack of human resources | Shortage of project team members/workers | [8,60] | 2 | 12 |

3.1.5. Personal Factors (PR)

3.2. Strategies to Improve the Mental Health of a Construction Workforce

| ID | Strategies | Risk Factors | Prevention Type | Directed Level | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Develop policies to eliminate harassment and bullying. | DR2 | Primary | I, O | [60] |

| S2 | Implement policies to promote equality regardless of gender, age, and race. | DR1, DR6, DR7, DR8 | Primary | I, O | [30] |

| S3 | Provide resources for assistance in coping with stressors such as financial, marital, and family issues. | PR6, PR7 | Tertiary | I | [18] |

| S4 | Offer workplace training opportunities. | OR7, OR9 | Secondary | O | [39] |

| S5 | Promote prompt resolution of workplace conflicts. | JR4 | Secondary | O | [54] |

| S6 | Implement measures to enhance cooperation between supervisors and subordinates. | OR4, PR3 | Primary | I, O | [69] |

| S7 | Foster strong workplace relationships. | OR4 | Primary | I, O | [70] |

| S8 | Redesign tasks to reduce interdependency. | JR7 | Secondary | I | [71] |

| S9 | Streamline tasks and shifts. | JR1 | Primary | I | [26] |

| S10 | Hire more personnel to reduce individual workloads. | JR1, OR12 | Primary | O | [20] |

| S11 | Provide counseling or other tools for managing mental health problems. | OR7 | Tertiary | O | [68] |

| S12 | Provide workers with constructive feedback. | OR10, PR9 | Secondary | I | [46] |

| S13 | Provide a supportive physical working environment. | HR1, HR2 | Primary | O | [72] |

| S14 | Provide opportunities for employees to express their opinions and participate in decision-making. | OR2, OR8 | Secondary | I | [66] |

| S15 | Provide opportunities for growth and promotion at work. | DR3 | Primary | I | [4] |

| S16 | Provide opportunities for workers to utilize their abilities and skills. | JR5 | Primary | I | [73] |

| S17 | Provide clear instructions, information, and work objectives. | JR2, JR3 | Primary | O | [9] |

| S18 | Implement a fair decision-making process. | OR5 | Primary | O | [10] |

| S19 | Provide adequate materials and equipment for performing assigned tasks. | DR4 | Primary | O | [26] |

| S20 | Promote cordial relationships with coworkers. | PR1, PR5 | Primary | I, O | [69] |

| S21 | Offer fair and adequate compensation. | PR6 | Primary | O | [10] |

| S22 | Provide opportunities for rewards and recognition. | OR6, PR9 | Primary | O | [53] |

| S23 | Foster a flexible work environment. | OR1 | Primary | I, O | [74] |

| S24 | Encourage open and transparent communication between team members. | OR11 | Primary | I, O | [75] |

| S25 | Implement better recruitment strategies. | DR1 | Primary | O | [56] |

| S26 | Increase opportunities for career development. | OR3 | Primary | O | [42] |

| S27 | Encourage task prioritization. | JR6 | Primary | I, O | [70] |

| S28 | Offer resources and support for managing stress. | JR8 | Secondary | O | [43] |

| S29 | Implement a thorough contract review process. | JR10 | Primary | O | [76] |

| S30 | Provide training on effective communication skills. | JR9, DR5 | Primary | O | [77] |

| S31 | Offer access to employee assistance programs. | PR2, PR8 | Secondary | O | [78] |

| S32 | Offer education and awareness programs. | PR4 | Primary | O | [5,79] |

4. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.; Feng, Y.; London, K. Theorizing to improve mental health in multicultural construction industries: An intercultural coping model. Buildings 2021, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Boadu, E.F. Domains of psychosocial risk factors affecting young construction workers: A systematic review. Buildings 2022, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherratt, F. Shaping the discourse of worker health in the UK construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, L. Uncovered: The Truth behind Construction’s Mental Health. Available online: https://www.constructionnews.co.uk/health-and-safety/mind-matters/uncovered-the-truth-behind-constructions-mental-health-27-04-2017/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- BCBuildingTrades. 83% of Construction Workers Have Experienced a Mental Health Issue. 2020. Available online: https://bcbuildingtrades.org/83-of-construction-workers-have-experienced-a-mental-health-issue/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Blair Winkler, R.; Middleton, C.; Remes, O. A Review on the Prevalence of Poor Mental Health in the Construction Industry. Healthcare 2020, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Impact of Covid-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepu, N.; Kermanshachi, S.; Pamidimukkala, A. Long-Term Physical and Mental Health Impacts of COVID-19 on Construction Workers. In International Conference on Transportation and Development 2024; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; pp. 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- London, K.A.; Meade, T.; McLachlan, C. Healthier Construction: Conceptualising Transformation of Mental Health Outcomes through an Integrated Supply Chain Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Tetteh, M.O. Staff resilience and coping behavior as protective factors for mental health among construction tradesmen. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 20, 671–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.M.; Buckner-Petty, S.; Evanoff, B.A.; Gage, B.F. Predictors of long-term opioid use and opioid use disorder among construction workers: Analysis of claims data. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.; Iacono, A.; Kolla, G.; Nunez, E.; Leece, P.; Wang, T.; Campbell, T.; Auger, C.; Boyce, N.; Doolittle, M.; et al. Lives Lost to Opioid Toxicity Among Ontarians Who Worked in Construction; Ontario Drug Policy Research Network: Toronto, ON, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, W.S.; Roelofs, C.; Punnett, L. Work environment factors and prevention of opioid-related deaths. Am. J. Public health 2020, 110, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental ill-health risk factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Boadu, E.F.; Dansoh, A.; Fagbenro, R.K. A scoping review of research on mental health conditions among young construction workers. Constr. Innov. 2023, 25, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A systematic review of mental stressors in the construction industry. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Hon, C.K.; Darko, A. Review of global mental health research in the construction industry: A science mapping approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hon, C.K.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B. The relationship between psychosocial hazards and mental health in the construction industry: A meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzad, H.; Teimoory, A.; Mousavi, S.J.; Bayramova, A.; Edwards, D.J. Mental Health Causation in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Review Employing a Psychological Safety Climate Model. Buildings 2023, 13, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S.; Rasagopalasingam, V. The causes and effects of work stress in construction project managers: The case in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2017, 17, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.; Oyeyipo, O.; Ojelabi, R.; Patience, T.O. Balancing the female identity in the construction industry. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 24, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotimi, F.E.; Burfoot, M.; Naismith, N.; Mohaghegh, M.; Brauner, M. A systematic review of the mental health of women in construction: Future research directions. Build. Res. Inf. 2023, 51, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, L.; Conroy, N.; Barr, W. What late-career and retired women engineers tell us: Gender challenges in historical context. Eng. Stud. 2019, 11, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Occupational challenges of women in construction industry: Development of overcoming strategies using Delphi technique. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2023, 15, 04522028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, M.; Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S.; Akhavian, R. Investigation of the barriers and their overcoming solutions to women’s involvement in the U.S. Construction industry. In Construction Research Congress 2020; El Asmar, M., Grau, D., Tang, P., Eds.; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 810–818. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Feng, Y.; London, K.; Zhang, P. Influence of personal characteristics and environmental stressors on mental health for multicultural construction workplaces in Australia. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaskati, D.; Kermanshachi, S.; Pamidimukkala, A. A Review on the Mental Health Stressors of Construction Workers. In International Conference on Transportation and Development 2024; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Regis, M.F.; Alberte, E.P.V.; dos Santos Lima, D.; Freitas, R.L.S. Women in construction: Shortcomings, difficulties, and good practices. Engineering. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 26, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T.; Giggins, H.; Ranasinghe, U. A critical analysis of risk factors and strategies to improve mental health issues of construction workers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.O.; Jones, W.; Unuigbe, M. Occupational stress management for UK construction professionals Understanding the causes and strategies for improvement. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 17, 819–832. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsoom, A.; Mughees, A.; Safdar, U.; Afsar, B.; Badar ul Ali, Z. Intrinsic psychosocial stressors and construction worker productivity: Impact of employee age and industry experience. Ekon. Istraz. 2018, 31, 1880–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhu, F.; Sun, X. Influencing factors of construction professionals’ burnout in China: A sequential mixed-method approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 3215–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Chiang, Y.H.; Wong, F.K.W.; Liang, S.; Abidoye, F.A. Work–life balance for construction manual workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, M.T.; Romo, P.E.; de la Hoz, R.E.; Villamor, J.M.; Mahíllo-Fernández, I. Anxiety and depression predict musculoskeletal disorders in health care workers. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2017, 72, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, S.G.; Herrero, C.; Egbu, C.; Fong, D. Integrated model for the stressors, stress, stress-coping behaviour of construction project managers in the UK. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 761–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.; Sun, C.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B.; Biggs, H.C. Psychosocial hazards affecting mental health in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 31, 3165–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.; Govender, R.; Edwards, P.; Cattell, K. Work-related contact, work-life conflict, psychological distress, and sleep problems experienced by construction professionals: An integrated explanatory model. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 36, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodanwala, T.C.; Shrestha, P.; Santoso, D.S. Role conflict related job stress among construction professionals: The moderating role of age and organization tenure. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.; Samanmali, R.; De Silva, H.L. Managing occupational stress of professionals in large construction projects. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Y. The effect of political skill on relationship quality in construction projects: The mediating effect of cooperative conflict management styles. Proj. Manag. J. 2021, 52, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H.; Zhang, R.P. Job quality and construction workers’ mental health: Life course perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Wang, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X. Psychosocial factors for safety performance of construction workers: Taking stock and looking forward. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, T.; Hasan, A.; Kamardeen, I. A systematic review of factors influencing the implementation of health promotion programs in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 2554–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimmieson, N.L.; Tucker, M.K.; Bordia, P. An Assessment of Psychosocial Hazards in the Workplace. 2016. Available online: https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/12317/paw-report.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Rodriguez, F.S.; Spilski, J.; Hekele, F.; Beese, N.O.; Lachmann, T. Physical and cognitive demands of work in building construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 27, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Poudel, L.; Bhandari, N.; Adhikari, N.; Shrestha, B.; Poudel, B.; Bishwokarma, A.; Kuikel, B.S.; Timalsena, D.; Paneru, B.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among construction workers in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Arango, D.; Vasquez-Hernandez, A.; Botero-Botero, L.F. Assessment of subjective workplace well-being of construction workers: A bottom-up approach. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 36, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Sheffield, D. Mental health shame of UK construction workers: Relationship with masculinity, work motivation, and self-compassion. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Y Organ. 2019, 35, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, R.R.; Sawang, S. Construction workers’ well-being: What leads to depression, anxiety, and stress? J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, R.; Duncan, A. Mental Health in the Construction Industry Scoping Study; BRANZ: Jugeford, New Zealand, 2018; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, O.; Loosemore, M.; Fini, A.A.F. Construction workforce’s mental health: Research and policy alignment in the Australian construction industry. Buildings 2023, 13, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. Mental health in the construction industry. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Frimpong, S.; Su, Z. Work stressors, coping strategies, and poor mental health in the Chinese construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Xiaohua, J.; Osei-Kyei, R. Critical analysis of mental health research among construction project professionals. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 19, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Z.M.; San Santoso, D.; Dodanwala, T.C. Effects of demotivational managerial practices on job satisfaction and job performance: Empirical evidence from Myanmar’s construction industry. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2023, 67, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, M.; Gambatese, J.; Hernandez, S. What do construction workers really want? A study about representation, importance, and perception of US construction occupational rewards. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyllon, M.; Vallas, S.P.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Garverich, S.; Weinstein, D.; Owens, K.; Lincoln, A.K. Mental health stigma and wellbeing among commercial construction workers: A mixed methods study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of job stressors and stress on the safety behavior and accidents of construction workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Turner, M. Promoting construction workers’ health: A multi-level system perspective. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, G.K.; Adeyeye, G.M.; Opawole, A.; Kajimo-Shakantu, K. Gender differences in workplace stress response strategies of quantity surveyors in Southwestern Nigeria. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2019, 37, 718–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerlein, J.T.; Eyllon, M.; Garverich, S.; Weinstein, D.; Manjourides, J.; Vallas, S.P.; Lincoln, A.K. Associations between work-related factors and psychological distress among construction workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Natarajan, R.; Dasgupta, C. Prevalence and risk factors for depression, anxiety, and stress among foreign construction workers in Singapore—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Lingard, H. Examining the interaction between bodily pain and mental health of construction workers. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.; Maheen, H.; Currier, D.; LaMontagne, A.D. Male suicide among construction workers in Australia: A qualitative analysis of the major stressors precipitating death. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, H.; Bullock, H.; Chouliara, N. Enablers and barriers to mental health initiatives in construction SMEs. Occup. Med. 2023, 73, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurelius, K.; Söderberg, M.; Wahlström, V.; Waern, M.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Åberg, M. Perceptions of mental health, suicide and working conditions in the construction industry—A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.A.; Gunning, J.G. Strategies to improve mental health and well-being within the UK construction industry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Manag. Procure. Law 2020, 173, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaraweera, A.; Jayasanka, T.A.D.K.; Gamage, V.; Alankarage, S.; Rameezdeen, R. Conceptual Framework for Suicide Prevention Process in Construction. In Proceedings of the 45th Australasian Universities Building Education Association Conference, Liverpool City, Australia, 23–25 November 2022; pp. 757–766. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Naslund, J.A. Measures to improve the mental health of construction personnel based on expert opinions. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C.; Leduc, C.; Maxwell, M.; Aust, B.; Amann, B.L.; Cerga-Pashoja, A.; Coppens, E.; Couwenbergh, C.; O’Connor, C.; Arensman, E.; et al. Evidence for implementation of interventions to promote mental health in the workplace: A systematic scoping review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enshassi, A.; Al-Swaity, E.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Choudhry, R. Coping behaviors to deal with stress and stressor consequences among construction professionals. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2018, 23, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Leung, M.-Y.; Cooper, C. Focus group study to explore critical factors for managing stress of construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, J.; Ajayi, S.O.; Oyegoke, A.S. Alcohol and substance misuse in the construction industry. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 27, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardeen, I.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Personal Characteristics Moderate Work Stress in Construction Professionals. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Akinyemi, T.A. Conceptualizing the dynamics of mental health among construction supervisors. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2593–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Lim, S.; Chi, S. Impact of work environment and occupational stress on safety behavior of individual construction workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.; Naslund, J.A.; Hon, C.K.; Belonwu, C.; Yang, J. Exploring the barriers to and motivators for using digital mental health interventions among construction personnel in Nigeria: Qualitative study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e18969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.C. Evaluation of multi-level intervention strategies for a psychologically healthy construction workplace in Nigeria. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 19, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, M.; Szóstak, M. Impact of alcohol on occupational health and safety in the construction industry at workplaces with scaffoldings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Risk Factor | Description | Source | Frequency | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JR1 | Work overload | Heavy workload demands that require working under pressure at a rapid pace for extended periods of time | [5,36] | 32 | 1 |

| JR2 | Role ambiguity | Ill-defined job duties | [27,38] | 27 | 2 |

| JR3 | Role conflict | Assignment of incompatible tasks | [38,39] | 25 | 3 |

| JR4 | Interpersonal conflict | Tensions and disagreements between employees in the workplace | [19,40] | 20 | 4 |

| JR5 | Work underload | Underutilization of skills, boring and repetitive work | [41,42] | 16 | 5 |

| JR6 | Task interdependency | Two or more tasks that depend on one another to complete a goal | [2,43] | 13 | 6 |

| JR7 | Cognitive demands | Work demands that require high levels of cognitive vigilance and alertness | [44,45] | 7 | 7 |

| JR8 | Emotional demands | Work demands that require dealing with people in different interpersonal contexts | [44,46] | 4 | 8 |

| JR9 | Client demand | Clients’ expectations and requirements pertaining to project costs and schedules | [36] | 1 | 9 |

| JR10 | Contract pressure | Stress induced by contractual obligations | [36] | 1 | 10 |

| ID | Risk Factor | Description | Source | Frequency | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR1 | Lack of social support | Poor social interaction with co-workers, friends, and family | [5,61] | 22 | 1 |

| PR2 | Type A behavior | Type A behavior is manifested in competitive, aggressive, and time-driven actions. | [29,62] | 18 | 2 |

| PR3 | Problem(s) with superior | Poor relationship with supervisor | [12,63] | 13 | 3 |

| PR4 | Alcohol and drug use | Substance use caused by job-related physical illnesses and/or stress | [64] | 11 | 4 |

| PR5 | Social isolation | The feeling of being alone or disconnected from others | [31,59] | 6 | 5 |

| PR6 | Financial insecurity | Fears regarding inadequate income | [35,37] | 4 | 6 |

| PR7 | Marital Status | Stress based on relationship problems | [16,30] | 4 | 7 |

| PR8 | Family conflicts | Disputes or strained relationships with family | [35,43] | 3 | 8 |

| PR9 | Loss of control | The degree to which individuals perceive the relationship between their personal actions and outcomes | [27,54] | 2 | 9 |

| PR10 | Fear of failure | Fear of experiencing negative outcomes | [51,55] | 2 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Almaskati, D.N. Mental Health in Construction Industry: A Global Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050802

Pamidimukkala A, Kermanshachi S, Almaskati DN. Mental Health in Construction Industry: A Global Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050802

Chicago/Turabian StylePamidimukkala, Apurva, Sharareh Kermanshachi, and Deema Nabeel Almaskati. 2025. "Mental Health in Construction Industry: A Global Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050802

APA StylePamidimukkala, A., Kermanshachi, S., & Almaskati, D. N. (2025). Mental Health in Construction Industry: A Global Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050802