Need for Recovery and Work–Family Conflict in the Armed Forces: A Latent Profile Analysis of Job Demands and Resources

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Role of Workload and the Perception of Work-Related Risks

1.2. The Role of Social Relationships, Feedback, and Meaningful Work

1.3. Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

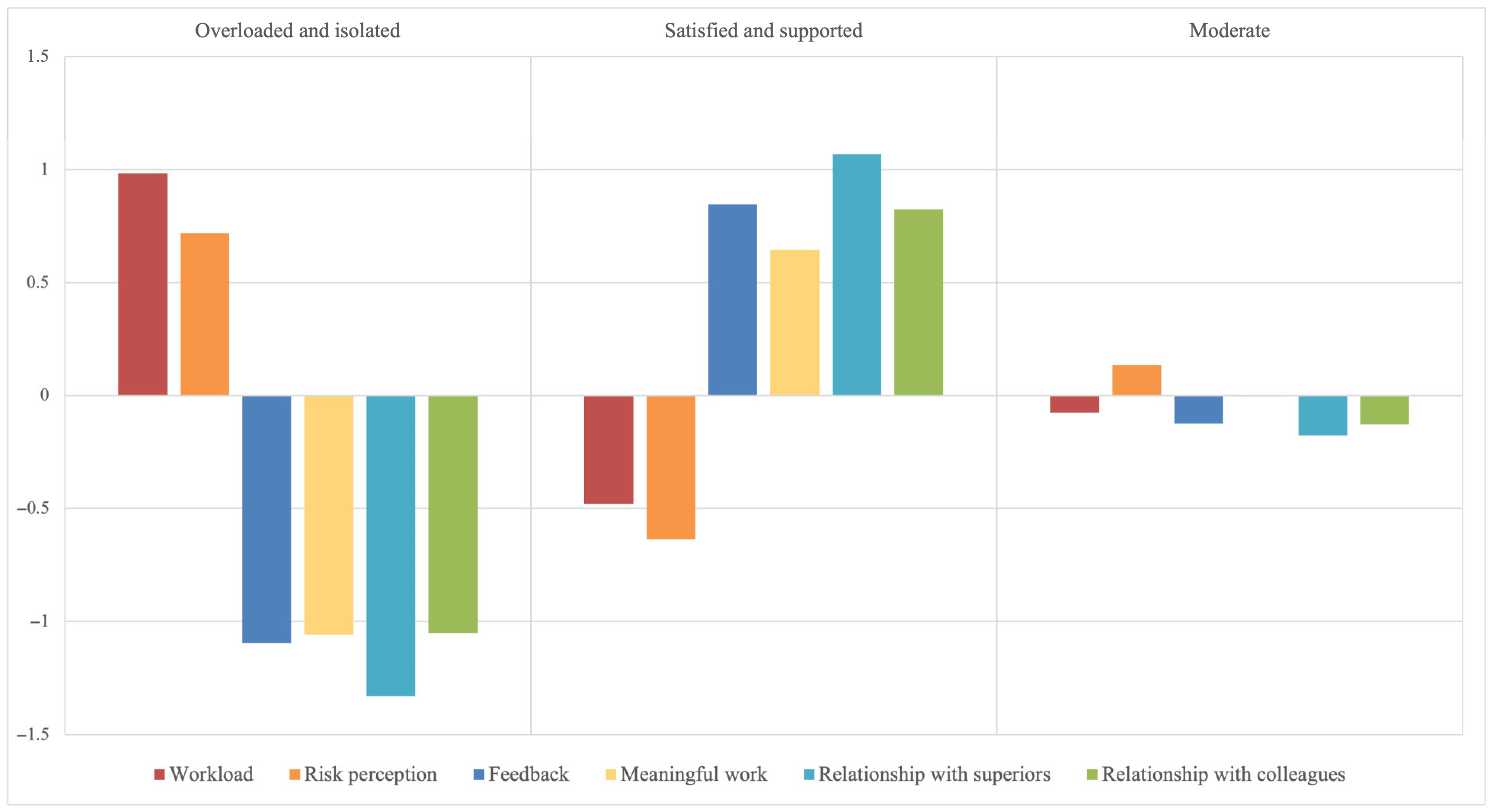

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, S. Occupational Stress in the Armed Forces: An Indian Army Perspective. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2015, 27, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevelink, S.A.M.; Jones, N.; Jones, M.; Dyball, D.; Khera, C.K.; Pernet, D.; MacCrimmon, S.; Murphy, D.; Hull, L.; Greenberg, N.; et al. Do Serving and Ex-Serving Personnel of the UK Armed Forces Seek Help for Perceived Stress, Emotional or Mental Health Problems? Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1556552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, M.K.; Bauer, G.F.; Gutzwiller, F.; Hämmig, O. Persistent Work-Life Conflict and Health Satisfaction—A Representative Longitudinal Study in Switzerland. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.A.; McCombs, K.M. Understanding Employee Work-life Conflict Experiences: Self-leadership Responses Involving Resource Management for Balancing Work, Family, and Professional Development. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2023, 96, 807–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, C.B.; Egan, J.; Bogue, J.; Sarma, K.M. Military Personnels’ Experience of Deployment: An Exploration of Psychological Trauma, Protective Influences, and Resilience. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Zijlstra, F.R.H. Job Characteristics and Off-Job Activities as Predictors of Need for Recovery, Well-Being, and Fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahern, J.; Worthen, M.; Masters, J.; Lippman, S.A.; Ozer, E.J.; Moos, R. The Challenges of Afghanistan and Iraq Veterans’ Transition from Military to Civilian Life and Approaches to Reconnection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvodic, A.; Dedic, G. Quality of Life and Anxiety in Military Personnel. Serbian J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019, 20, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, E.; Österberg, J.; Nilsson, J. Work-Life Balance among Newly Employed Officers—A Qualitative Study. Health Psychol. Rep. 2020, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Clements, A.J.; Hart, J. Working Conditions, Work–Life Conflict, and Well-Being in U.K. Prison Officers: The Role of Affective Rumination and Detachment. Crim. Justice Behav. 2017, 44, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Clements, A.J.; Hart, J. Job Demands, Resources and Mental Health in UK Prison Officers. Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, N.; Kinman, G. Job Demands, Resources and Work-Related Well-Being in UK Firefighters. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.S.; Son Hing, L.S.; Gnanakumaran, V.; Weiss, S.K.; Lero, D.S.; Hausdorf, P.A.; Daneman, D. Inspired but Tired: How Medical Faculty’s Job Demands and Resources Lead to Engagement, Work-Life Conflict, and Burnout. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 609639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, I.; Shelef, L.; Yavnai, N.; Todder, D.; Sarid, O. Burnout among Health Professionals in the IDF. J. Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamayantie, E. Contribution of Work and Family Demands on Job Satisfaction Through Work-Family Conflict. J. Manag. Mark. Rev. 2017, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Di Sipio, A. When Does Work Interfere with Teachers’ Private Life? An Application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G. Gender Differences in the Relationship between Work–Life Balance, Career Opportunities and General Health Perception. Sustainability 2021, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Jiménez, M.C.; Laguía, A.; Recio, P.; García-Guiu, C.; Pastor, A.; Edú-Valsania, S.; Molero, F.; Mikulincer, M.; Moriano, J.A. Secure Base Leadership in Military Training: Enhancing Organizational Identification and Resilience through Work Engagement. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1401574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, C.; Vandenberghe, C. Are They Created Equal? A Relative Weights Analysis of the Contributions of Job Demands and Resources to Well-Being and Turnover Intention. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 392–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Fernández-Martínez, M.D.M. Burnout in Spanish Security Forces during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, J.; Forbes, H.; Fear, N.T.; Dandeker, C.; Wessely, S. The Impact of the Conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan: A UK Perspective. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2011, 23, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.; Lambert, E.G.; Qureshi, H. Examining Police Officer Work Stress Using the Job Demands–Resources Model. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2017, 33, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, K.J.E.; Scheibe, S.; Frenzel, A.C.; Keller, M.M. Exceptional Circumstances: Changes in Teachers’ Work Characteristics and Well-Being during COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, F.; Panatik, S.A.; Sukor, M.S.M.; Rusbadrol, N. A Job Demand–Resource Model of Satisfaction with Work–Family Balance Among Academic Faculty: Mediating Roles of Psychological Capital, Work-to-Family Conflict, and Enrichment. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211006142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, C.; Soeters, J. Self-Perceptions of Soldiers under Threat: A Field Study of the Influence of Death Threat on Soldiers. Mil. Psychol. 2009, 21, S16–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elafandy, A.; El-Tantawy, A.; Bahi-Eldin, M.; Sayed, H. Burnout, Psychiatric Symptoms and Social Adjustment among Military Personnel. Suez Canal Univ. Med. J. 2021, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedtofte, M.S.; Elrond, A.F.; Erlangsen, A.; Nielsen, A.B.S.; Stoltenberg, C.D.G.; Marott, J.L.; Nissen, L.R.; Madsen, T. Combat Exposure and Risk of Suicide Attempt Among Danish Army Military Personnel. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 37375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva-Martinova, T.; Villeneuve, M.; Strickland, L.; Matheson, K. Occupational Role Stress in the Canadian Forces: Its Association with Individual and Organizational Well-Being. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2002, 34, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, R.M.; Camlin, C.S.; Fairbank, J.A.; Dunteman, G.H.; Wheeless, S.C. The Effects of Stress on Job Functioning of Military Men and Women. Armed Forces Soc. 2001, 27, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Tsai, B.-K. Effects of Social Support on the Stress-Health Relationship: Gender Comparison among Military Personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debets, M.; Scheepers, R.; Silkens, M.; Lombarts, K. Structural Equation Modelling Analysis on Relationships of Job Demands and Resources with Work Engagement, Burnout and Work Ability: An Observational Study among Physicians in Dutch Hospitals. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e062603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soucek, R.; Rupprecht, A. Supervisor Feedback as a Source of Work Engagement? The Contribution of Day-to-Day Feedback to Job Resources and Work Engagement. Eur. Work. Organ. Psychol. Pract. 2020, 14, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepito, C.L. The Effects of Work-Family Conflict on the Work Performance of Married Female Military Personnel of the Philippine Air Force. Int. J. Res. Publ. 2023, 136, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowhan, J.; Pike, K. Workload, Work–Life Interface, Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Job Demand–Resource Model Study during COVID-19. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 44, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisler, S.; Omansky, R.; Alenick, P.R.; Tumminia, A.M.; Eatough, E.M.; Johnson, R.C. Work-life Conflict and Employee Health: A Review. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2018, 23, e12157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimell, J.; Van Den Berg, M. Advancing an Understanding of the Body amid Transition from a Military Life. Cult. Psychol. 2020, 26, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Zippay, A. The Juggling Act: Managing Work-Life Conflict and Work-Life Balance. Fam. Soc. 2011, 92, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, K.A.; Richardson, S.M.; Pflieger, J.C.; Hawkins, S.A.; Stander, V.A. Influence of Work and Life Stressors on Marital Quality among Dual and Nondual Military Couples. J. Fam. Issues 2020, 41, 2045–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, M. Distress, Support, and Relationship Satisfaction during Military-Induced Separations: A Longitudinal Study among Spouses of Dutch Deployed Military Personnel. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, D.S.; Thompson, M.J.; Crawford, W.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Spillover and Crossover of Work Resources: A Test of the Positive Flow of Resources through Work–Family Enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, J.; Österberg, J. A Question of Time? Deployments, Dwell Time, and Work-Life Balance for Military Personnel in Scandinavia. Mil. Psychol. 2023, 35, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Mulé, E.; Courtright, S.H.; DeGeest, D.; Seong, J.-Y.; Hong, D.-S. Channeled Autonomy: The Joint Effects of Autonomy and Feedback on Team Performance Through Organizational Goal Clarity. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 2018–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G.M. Challenge versus Hindrance Job Demands and Well-being: A Diary Study on the Moderating Role of Job Resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. Examining Mediation Effects of Work Engagement Among Job Resources, Job Performance, and Turnover Intention. Perform. Improv. Q. 2017, 29, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Ropponen, A.; De Witte, H.; Schaufeli, W.B. Testing Demands and Resources as Determinants of Vitality among Different Employment Contract Groups. A Study in 30 European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Turunen, J. The Relative Importance of Various Job Resources for Work Engagement: A Concurrent and Follow-up Dominance Analysis. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2024, 27, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden-Eyiusta, C. Job Resources, Engagement, and Proactivity: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, R.; Mohd Asri, N.A.; Alias, N.E.; Jahya, A.; Koe, W.-L.; Krishnan, R. The Effect of Job Resources on Work Engagement: Does This Matter among Academics in Malaysia? Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nae, E.Y.; Moon, H.K.; Choi, B.K. Seeking Feedback but Unable to Improve Work Performance? Qualified Feedback from Trusted Supervisors Matters. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, M.; Van Der Heijden, B.; Rombaut, T.; Van Thielen, T. The Role of Feedback Quality and Organizational Cynicism for Affective Commitment Through Leader–Member Exchange. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.U.; Ye, B.J.; Kim, B.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.W. Association between Supervisors’ Behavior and Wage Workers’ Job Stress in Korea: Analysis of the Fourth Korean Working Conditions Survey. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 29, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazan, A.; Truţă, C.; Pavalache-Ilie, M. The Work-Life Conflict and Satisfaction with Life: Correlates and the Mediating Role of the Work-Family Conflict. Rom. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 21, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, T.; Lewin, A.; Woodall, K.; Cruz-Cano, R.; Thoma, M.; Stander, V.A. Gender Differences in Marital and Military Predictors of Service Member Career Satisfaction. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 1515–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkkinen, J.; Auvinen, E.; Mauno, S. Meaningful Work Protects Teachers’ Self-Rated Health under Stressors. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 4, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G.; Russo, L. Meaningful Work, Pleasure in Working, and the Moderating Effects of Deep Acting and COVID-19 on Nurses’ Work. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G.; Randazzo, N.A.; Macaluso, V. Teachers’ Work-Related Well-Being in Times of COVID-19: The Effects of Technostress and Online Teaching. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Murphy, W.; Singh, P. Reverse Mentoring, Job Crafting and Work-Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2021, 26, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.J.; Jiang, L. Reaping the Benefits of Meaningful Work: The Mediating versus Moderating Role of Work Engagement: Reaping the Benefits of Meaningful Work. Stress Health 2017, 33, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Lores, I.; Rolo-González, G.; Suárez, E.; Chinea-Montesdeoca, C. Meaningful Work, Work and Life Satisfaction: Spanish Adaptation of Work and Meaning Inventory Scale. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12151–12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Sinnott, S.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Carney, L.M.; Park, C.L.; Mazure, C.M.; Hoff, R. Meaningful Military Engagement among Male and Female Post-9/11 Veterans: An Examination of Correlates and Implications for Resilience. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2167–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusmargono, C.A.; Jaya, W.K.; Hadna, A.H.; Sumaryono, S. The Effect of Authentic Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior Mediated by Work Meaningfulness. J. Psychol. Behav. Stud. 2023, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, S. Female Managers’ Meaningful Work and Commitment: Organizational Contexts and Generational Differences. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, F.O.; Onyishi, I.E. Linking Perceived Organizational Frustration to Work Engagement: The Moderating Roles of Sense of Calling and Psychological Meaningfulness. J. Career Assess 2017, 26, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R.T.; Annen, H.; Eggimann, N.; Schneider, A.; Ruch, W. Assessing the “Good Life” in a Military Context: How Does Life and Work-Satisfaction Relate to Orientations to Happiness and Career-Success Among Swiss Professional Officers? Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.S.; Hawkins, S.A.; Gilreath, T.D.; Castro, C.A. Mental Health Outcomes Associated with Profiles of Risk and Resilience among U.S. Army Spouses. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neal, C.W.; Lavner, J.A.; Jensen, T.M.; Lucier-Greer, M. Mental Health Profiles of Depressive Symptoms and Personal Well-being among Active-duty Military Families. Fam. Process 2024, 63, 2367–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciotto, G. Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work: Uno Strumento per la Valutazione del Benessere nei Luoghi di Lavoro. Validazione e Applicazione dell’Adattamento Italiano. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10447/600254 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- van Veldhoven, M.J.P.M.; Prins, J.; van der Laken, P.A.; Dijkstra, L. QEEW 2.0: 42 Short Scales for Survey Research on Work, Well-Being and Performance; SKB: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, L.; Ghisleri, C. The Work-To-Family Conflict: Theories and Measures. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 15, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, B.E.; Perander, J.; Smecko, T.; Trask, J. Measuring Perceptions of Workplace Safety. J. Saf. Res. 1998, 29, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making Part I; MacLean, L.C., Ziemba, W.T., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2013; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S.L.; Moore, E.W.G.; Hull, D.M. Finding Latent Groups in Observed Data: A Primer on Latent Profile Analysis in Mplus for Applied Researchers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Auxiliary Variables in Mixture Modeling: Three-Step Approaches Using MPlus. Struct. Equ. Model. 2014, 21, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyn, K.E. Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling. In The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods: Statistical Analysis; Little, T.D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 551–611. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tein, J.-Y.; Coxe, S.; Cham, H. Statistical Power to Detect the Correct Number of Classes in Latent Profile Analysis. Struct. Equ. Model. 2013, 20, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, P.D.; Krasikova, D.V.; Vanhove, A.J.; Herian, M.N.; Lester, P.B. Stress and Emotional Well-Being in Military Organizations. In Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being; Perrewé, P.L., Rosen, C.C., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2013; Volume 11, pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Boga, D. Military Leadership and Resilience. In Handbook of Military Sciences; Sookermany, A.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Maddi, S.R. Relevance of Hardiness Assessment and Training to the Military Context. Mil. Psychol. 2007, 19, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reivich, K.J.; Seligman, M.E.P.; McBride, S. Master Resilience Training in the U.S. Army. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Workload | 2.13 (0.52) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Risk perception | 3.18 (0.87) | 0.376 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Meaningful work | 3.24 (0.44) | −0.273 ** | −0.167 * | 1 | |||||

| 4. Feedback | 2.63 (0.67) | −0.267 ** | −0.336 ** | 0.532 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Relationship with colleagues | 3.27 (0.52) | −0.340 ** | −0.312 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.412 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Relationship with superiors | 3.09 (0.61) | −0.455 ** | −0.426 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.562 ** | 0.599 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. Need for recovery | 1.85 (0.53) | 0.638 ** | 0.436 ** | −0.278 ** | −0.230 ** | −0.327 ** | −0.427 ** | 1 | |

| 8. Work–life conflict | 2.30 (0.62) | 0.695 ** | 0.538 ** | −0.304 ** | −0.292 ** | −0.354 ** | −0.507 ** | 0.743 ** | 1 |

| Models | Model Fit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | |

| 1-factor model | 3440.772 | 860 | 0.473 | 0.447 | 0.119 (0.115–0.123) | 0.122 |

| 2-factor model | 2858.950 | 858 | 0.592 | 0.571 | 0.105 (0.101–0.109) | 0.116 |

| 6-factor model | 1254.602 | 832 | 0.915 | 0.906 | 0.049 (0.043–0.055) | 0.078 |

| Models | AIC | BIC | SABIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-class model | 2021.260 | 2105.975 | 2028.741 | 0.79 |

| 3-class model | 1909.701 | 2036.849 | 1916.465 | 0.85 |

| 4-class model | 1906.305 | 2077.917 | 1915.352 | 0.84 |

| Profiles | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Need for Recovery | Work–Family Conflict | |

| Profile 1 “Overloaded and isolated” | 2.25 (0.59) | 2.83 (0.55) |

| Profile 2 “Satisfied and supported” | 1.58 (0.44) | 1.95 (0.62) |

| Profile 3 “Moderate” | 1.86 (0.44) | 2.31 (0.50) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pace, F.; Moavero, C.; Cusimano, G.; Sciotto, G. Need for Recovery and Work–Family Conflict in the Armed Forces: A Latent Profile Analysis of Job Demands and Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050795

Pace F, Moavero C, Cusimano G, Sciotto G. Need for Recovery and Work–Family Conflict in the Armed Forces: A Latent Profile Analysis of Job Demands and Resources. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050795

Chicago/Turabian StylePace, Francesco, Cristina Moavero, Giuditta Cusimano, and Giulia Sciotto. 2025. "Need for Recovery and Work–Family Conflict in the Armed Forces: A Latent Profile Analysis of Job Demands and Resources" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050795

APA StylePace, F., Moavero, C., Cusimano, G., & Sciotto, G. (2025). Need for Recovery and Work–Family Conflict in the Armed Forces: A Latent Profile Analysis of Job Demands and Resources. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050795