Exploring Cultural and Age-Specific Preferences to Develop a Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention for CHamorus and Filipinos in Guam—Findings from a Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment and Eligibility

2.2. Method

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Focus Group Themes

3.2.1. Primary Source of Knowledge About CRC and Screening Is Derived from Family Experiences

“More recently, my knowledge became much more personal when my nephew was diagnosed several years ago at the age of 37 with stage four colorectal cancer. He died two years later…so I learned a lot about the personal impact on an individual, especially a young man and the family through that experience.”—Female, aged 50+

“It’s kind of, we lived through the same experience. I live vicariously through him. And it gave a face to—it became more concrete…more understandable. Now it’s something that I can repeat myself. Right? I can tell others the story. Because there’s a personal touch to it. There’s an emotion attached to it. I understand it more. And I remember it more.”—Female, 40–49 years old

3.2.2. More Awareness and Outreach Needed for Men

“I’m not too familiar with it, but actually, had a friend who died from prostate cancer. But, you know, I know it’s from the same area there (laughs). That’s pretty much what I know about it.”—Male, 40–49 years old

“Now we’re having all sorts of society evolving around that to make sure that we watch women as they go through. Men seem to stay away from that space. ‘If I’m fine, I’m good,’ until a moment in time when you actually have to go in. And then you find out that two years ago, or last year that could have been picked [up].”—Male, aged 50+

“We always hear breast cancer awareness. What about men? I mean, no offense to the female aspect. But like I know more about breasts than that what’s going on with us…... My sisters, they share it, you know, “We’re gonna go get our mammograms,” I-I never said I’m gonna go get, “you know”, to my family. I think the emphasis is not more with the men, but with the women…maybe more awareness with us, you know?”—Male, 40–49 years old

“My husband, who’s 65, he had to ask for his colonoscopy. It was not something that his primary physician who—my husband’s very happy with him, but my husband just underwent a colonoscopy, two weeks ago. I asked him, I said, “Did your doctor bring it up or did you have to ask for it?” And he said, “I had to ask. It wasn’t brought up.” And so I do think that there’s perhaps a gender difference in terms of who gets routinely asked or routinely educated and who doesn’t.”—Female, aged 50+

“Well…I mean, I’m 48. My doc, I don’t think that my doctor’s ever brought that up one time with me that maybe I should get screened.”—Male, 40–49 years old

“Just speaking on behalf of my uncle, who’s [sic] never went to the doctor. Never and then just recently, he almost died. He was like, ‘No, I’m still okay. And he went to the doctor and they found out that, you know, he was bleeding inside…and for the years that he’s never been to the doctor and we always ask him why you don’t want to go to the doctor. He said, just like that, “I’m a guy, I don’t need to. I’m okay. I’m okay.” But inside, you know, you’re really hurting. But they just suck it in and drive on, you know?”—Male, 40–49 years old

“There’s the modern-day Chamorro culture that—I grew up in where, you know, you have to be hard, you know, you have to pro-project this image of, you know, a tough guy image and sometimes—That works towards your detriment.”—Male, 40–49 years old

“Other people have this kind of false equivocation with going to the doctor where, ‘Well, I know people who are healthy until they went to the doctor and then…’ And so it might be…a fear of what the doctor will tell you.”—Male, 40–49 years old

“Some people I know do not want to know. Of what they might find. If they do the colonoscopy. It’s like that in itself is daunting, outta sight, out of mind type mentality. And yet I think that, that, continues to let colorectal cancer be the second leading cancer among men.”—Male, aged 50+

“The doctor should be telling us, almost like a two minute warning. It’s like, ‘Hey man, you know, you’re how old, okay. In two years, you know don’t forget, you’re gonna have to do this n-next year.’ ‘Hey, it’s you know, maybe next year you might want to consider doing this.’ And then the year happens like, ‘Okay, so, this year, you know, you should be doing this.’”—Male, 40–49 years old

“I would like for my doctor, any, even if it’s, based on the numbers of people that are contracting it or acquiring it or whatever the case may be on Guam…if I fit that demographic, can you please bring it up to me? You please let me know.”—Male, 40–49 years old

3.2.3. Hearing Personal Narratives About CRC Makes a Difference

“When you’re talking about colorectal cancer, it’s—you’re talking about a very uncomfortable part of one’s body image. We don’t have a comfortable language to talk about it. So being able to hear other people’s stories, it sort of melts the ice and it creates a comfort and sense of “Hey, it’s, it’s okay.” Okayness to talk about something which in our cultures we’re raised to think of as being very, very private, anything related to elimination or sexuality is either very personal and private or it’s made fun of, made jokes about.”—Female, aged 50+

“I’m especially big on, that you’d want to develop more storytellers, except the story is real. They would not be telling some make believe thing but, their personal accounts or people’s personal accounts of, surviving or in some cases, people, their loved one’s not surviving, you know? And that you don’t need a degree. You don’t need extensive training. You need to just really have the passion that will move people. Cause that’s the biggest thing. I think the personal, the personal connection that you make that will move people.”—Male, aged 50+

“When I had coworkers who were older than I was, who never—and whenever we talk about this they’re so ‘No, I would never do this.’ So adamant. ‘I would never do this. They’re never gonna do that to me. It’s not manly for them (light laughter in the group) to do this to me.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, until you get that thing, and then you find out that you’re going to die.’ I got both of them- my coworkers to go do it. And one of them had to have numerous polyps removed! And I remember him coming back to me and saying, ‘You know what, thank you for that really, real life talk about the, consequences- if we don’t get checked.’”—Male, aged 50+

3.2.4. Screening Is Motivated by Strong Family Values and an Intergenerational Consciousness

“Because like my mom died of cancer. And when we found that she had cancer, we were there with her as a unit, as a family, the moment that she found out until the day she died, you know? So I think it’s best for my family. We did it as a family unit. So if let’s say I found out that I do have it, then at least my family unit—now we need to kick on the bucket and start learning what’s going on, what needs to be done.”—Male, 40–49 years old

“So in my family, how we talk about health issues is, um, looking again at how we value our family…But the conversation also begins with, how old are your children or, oh your daughter is gonna get married. You know, we’d like you to stay longer. We’d like you to be with us. And when you’re with us, we’d like you to be healthy. So if this is something that we need to do and no matter how inconvenient and unpleasant it is, but- if it means we’re gonna enjoy the family more because you’ll be here longer and you’ll be healthy with a good quantity of life, then it’s something that we have to do. And so we always go back to not just ourselves, but who are going to be affected by the choices that we make, by the health choices that we make now. And so that’s how we deal with it with our family.”—Female, aged 50+

“I think an important message to get across because of the family focus is to emphasize love. And what I mean by that is to get across the message, that screening is one of the most loving things you can do for your family. You know, they want you to be around, you wanna be around for your family…I remember when I began using that messaging in my own family and at first, you know, they would laugh at me and think that was sort of funny. But now we talk about it as sort of something, we kind of remind each other, taking care of yourself, screening is about taking care of yourself and it’s the most loving thing you can do for your family.”—Female, aged 50+

“I think the incentive, for everyone is—it’s true that we tend to not want to confront things or put things off. But the incentive is to think about your family or your spouse or your friends, or the people that rely on you that who would not be there. If you have co—polyps and you never have it checked. Because the impact to them is tremendous. I mean, you would, you wanna be there for them. For many, many, many reasons. And I think that’s a message that we can all promote in all kinds of different ways.”—Male, aged 50+

“I still think that family is still highly valued. You know, so if my mom back then were kind of resisting to getting screened [sic]. It’d be like, well, don’t, you wanna see me graduate, address your grandchildren, you know, grow up and get married…It like not just what impacts you. But how it impacts your other family, whether it’s your spouse or your children, you wanna be around for the long haul. And knowing that if you can get screened early and- they can, you know, again, get screened early and deal with the issue then? Then you have a better chance of, I guess, you know, meeting that goal.”—Female, aged 50+

3.3. Focus Group Poll Results

3.3.1. Community Health Educator (CHE) Characteristics

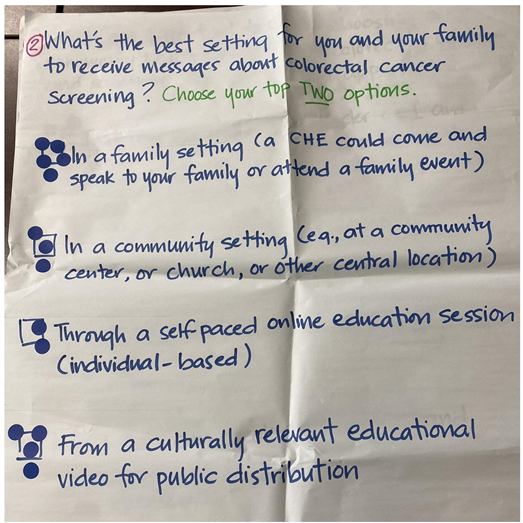

3.3.2. Preferred Methods of Intervention Delivery

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHE | Community Health Educator |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| EOCRC | Early Onset Colorectal Cancer |

| FG | Focus Groups |

| U.S. | United States of America |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Interview Guide Questions

| Initial Question | Follow-Up Probes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix A.2. Example of Paper Poll Used Within Focus Groups

References

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER). Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Bhimla, A.; Mann-Barnes, T.; Park, H.; Yeh, M.C.; Do, P.; Aczon, F.; Ma, G. Effects of neighborhood ethnic density and psychosocial factors on colorectal cancer screening behavior among Asian American adults, greater Philadelphia and New Jersey. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, J.B.; Chen, J.J.; Braun, K.L. Colorectal cancer screening compliance among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavidez, G.A.; Zgodic, A.; Zahnd, W.E.; Eberth, J.M. Disparities in meeting USPSTF breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening guidelines among women in the United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Diaz, T.P.; Badowski, G.; Bordallo, R.; Mummert, A.; Palaganas, H.; Teria, R.; Dulana, L. Guam Cancer Facts and Figures: 2013–2017; Guam Department of Public Health and Social Services: Hagatña, Guam, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. 2020 Island Areas Censuses Data on Demographic, Social, Economic and Housing Characteristics Now Available for Guam. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/2020-island-areas-guam.html (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health. BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/ (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Nagata, M.; Miyagi, K.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Kuwada, S.K. Multiethnic Trends in Early Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badowski, G.; Teria, R.; Nagata, M.; Legaspi, J.; Dulana, L.J.; Bordallo, R.; Hernandez, B. Ethnic disparities in early-onset colorectal cancer incidence, screening rates and risk factors prevalence in Guam. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 43, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasako-Schmucker, D.L.; Peng, Y.; Cobb, J.; Buchanan, L.R.; Xiong, K.Z.; Mercer, S.L.; Sabatino, S.A.; Melillo, S.; Remington, P.L.; Kumanyika, S.K.; et al. Community health workers to increase cancer screening: 3 Community guide systematic reviews. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 64, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuaresma, C.F.; Sy, A.U.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ho, R.C.S.; Gildengorin, G.L.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Jo, A.M.; Tong, E.K.; Kagawa-Singer, M.; Stewart, S.L. Results of a lay health education intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among Filipino Americans: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2018, 124 (Suppl. S7), 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, M.A.; Cadet, D.; Hunley, R.; Retnam, R.; Arezo, S.; Sheppard, V.B. Health equity and colorectal cancer awareness: A community health educator initiative. J. Cancer Educ. 2023, 38, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, T.; Chan, D.N.S.; Nguyen, K.T.; Choi, K.C.; So, W.K.W. Effectiveness of community health worker-led initiatives in enhancing colorectal cancer screening uptake in racial and ethnic minority populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2024, 47, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, D.E.; Snyder, F.R.; Miguel-Majors, S.S.; Bailey, L.O.; Springfield, S. Screen to save: Results from NCI’s colorectal cancer outreach and screening initiative to promote awareness and knowledge of colorectal cancer in racial/ethnic and rural populations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark Prev. 2020, 29, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, R.; Peters, R.; Beck, L.L.; Fifita, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Guevara, L.; Palmer, P.H.; Tanjasiri, S.P. A Pacific Islander organization's approach towards increasing community colorectal cancer knowledge and beliefs. Californian J. Health Promot. 2013, 11, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Archibald, J.-A.; Lee-Morgan, J.; De Santolo, J.; Smith, L.T. (Eds.) Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vaka, S.; Brannelly, T.; Huntington, A. Getting to the heart of the story: Using talanoa to explore Pacific mental health. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 37, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaioleti, T.M. Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato J. Educ. 2006, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecun, A.; Hafoka, I.; ‘Ulu‘ave-Hafoka, M. Talanoa: Tongan epistemology and Indigenous research method. AlterNative 2018, 14, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, K.L.; Stately, A.; Evans-Campbell, T.; Simoni, J.M.; Duran, B.; Schultz, K.; Guerrero, D. The Field Research Survival Guide; “Indigenist” Collaborative Research Efforts in Native American Communities; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 146–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descript Version 49.1.1; Descript Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.descript.com/transcription?pscd=get.descript.com&ps_partner_key=c2VtYW50aWNsYWJz&sid=1-b-2f2172be737d192bb76f15cd13a9ca50&msclkid=2f2172be737d192bb76f15cd13a9ca50&ps_xid=7Gi38USi0GzIiE&gsxid=7Gi38USi0GzIiE&gspk=c2VtYW50aWNsYWJz (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Cornish, F.; Gillespie, A.; Zittoun, T. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. In Collaborative Analysis of Qualitative Data; SAGE Publications: Ventura County, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedoose Version 9.0.17; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: www.dedoose.com (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Camacho, S.G.; Ta, W.; Haitsuka, K.; Velasco, S.; Ablao, R.A.; Fuamatu, F.J.B.; Cruz, E.; Kanuha, V.K.; Spencer, M. Honoring inágofli’e’ and alofa: Developing a culturally grounded health promotion model for queer and transgender Pacific Islanders. Genealogy 2024, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Iyechad, L. Inafa’maolek: Striving for Harmony. Available online: https://www.guampedia.com/inafamaolek/ (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Macaraeg, J.; Bersamira, C.S. Intersecting kapwa, resilience, and empowerment: A case study of Filipinos in Hawai‘i during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Am. J. Psychol 2024, 15, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, V.; Beasley, D.; Ye, C.; Halpin, S.N.; Gauthreaux, N.; Escoffery, C.; Chawla, S. Barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening in African-American Men. Dig. Sci. Dis. 2022, 67, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, C.M.; Vargas, N.; Bradley, S.; Parra-Medina, D. Barriers and facilitators of colonoscopy screening among Latino men in a colorectal cancer screening promotion program. Am. J. Mens. Health 2023, 17, 15579883231179325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldman, R.E.; Diaz, J.A.; Kim, I. Perspectives of colorectal cancer risk and screening among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans: Stigma and misperceptions. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, M.L.; Bowman, I.K. Histories of wonder, futures of wonder: Chamorro activist identity, community, and leadership in “The Legend of Gadao” and “The Women Who Saved Guåhan from a Giant Fish”. Marvels Tales 2016, 30, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K.A.; Pritchard, D.; McElfish, P.A. An intersectional mixed methods approach to Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander men’s health. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2019, 10, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennelly, M.O.; Sly, J.R.; Villagra, C.; Jandorf, L. Narrative message targets within the decision-making process to undergo screening colonoscopy among Latinos: A qualitative study. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Reeder, T.; Abel, G. I can’t get my husband to go and have a colonoscopy’: Gender and screening for colorectal cancer. Health 2012, 16, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, A.M. Meeting Chamorro women’s health care needs: Examining the cultural impact of mamahlao on gynaecological screening. Pac. Health Dialog 2010, 16, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- DeLisle, C.T. Unequal Sisters. In A History of Chamorro Nurse-Midwives in Guam and a “Placental Politics” for Indigenous Feminism; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 309–327. Available online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue37/delisle.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Yoo, G.J.; Le, M.-N.; Vong, S.; Lagman, R.; Lam, A. Cervical cancer screening attitudes and behaviors of young Asian American women. J. Cancer Educ. 2024, 26, 740–746. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3880118/ (accessed on 15 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, J.B.B.; Laurino, M.Y.; San Juan, M.D.; Cauyan, J.M.L.; Tumulak, M.J.R.; Ventura, E.R. Risk perception and screening behavior of Filipino women at risk for breast cancer: Implications for cancer genetic counseling. J. Community Genet. 2019, 10, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromhead, C.; Wihongi, H.; Sherman, S.M.; Crengle, S.; Grant, J.; Martin, G.; Maxwell, A.; McPherson, G.; Puloka, A.; Reid, S.; et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling among never-and under-screened Indigenous Māori, Pacific and Asian women in Aotearoa New Zealand: A feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Fredericks, B.; Mills, K.; Anderson, D. “Yarning” as a method for community-based health research with indigenous women: The indigenous women’s wellness research program. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.L.; Lee, N.; Anderson, K.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; Cunningham, J.; Condon, J.R.; Garvey, G.; Tong, A.; Moore, S.; Maher, C.; et al. Under-screened Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s perspectives on cervical screening. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briant, K.J.; Halter, A.; Marchello, N.; Escareño, M.; Thompson, B. The power of digital storytelling as a culturally relevant health promotion tool. Health Promot Pract. 2016, 17, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, V.; Kandahari, N.; Curiel, D.; Carter, A.; Somkin, C.P.; Allen, A.M. Digital storytelling as a tool to increase colorectal cancer screening intention in a Latinx church community. J. Cancer Educ. 2023, 38, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.; Barrington, W.E.; Briant, K.J.; Kupay, E.; Carosso, E.; Gonzalez, N.E.; Gonzalez, V.J. Educating Latinas about cervical cancer and HPV: A pilot randomized study. Cancer Causes Control 2019, 30, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacic, M.B.; Gertz, S.E. Leveraging stories to promote health and prevent cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2022, 15, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Hyams, T.; Laurino, M.; Woolley, T.; Cohen, S.; Leppig, K.A.; Jarvik, G. Development of FamilyTalk: An intervention to support communication and educate families about colorectal cancer risk. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lowery, J.T.; Horick, N.; Kinney, A.Y.; Finkelstein, D.M.; Garrett, K.; Haile, R.W.; Lindor, N.M.; Newcomb, P.A.; Sandler, R.S.; Burke, C.; et al. A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Participants (n = 25) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 14 | 56 |

| Men | 11 | 44 |

| Age | ||

| 40–49 | 11 | 44 |

| 50 and above | 14 | 56 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| CHamoru | 15 | 60 |

| Filipino | 8 | 32 |

| Mixed CHamoru/Filipino | 2 | 1 |

| Healthcare Access | ||

| Has regular clinic | 23 | 92 |

| Has regular provider | 21 | 84 |

| Has health insurance | 24 | 96 |

| CRC Screening | ||

| Ever had a FIT/FOBT | 6 | 24 |

| Ever had a colonoscopy | 14 | 56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diaz, T.P.; Camacho, S.G.; Elmore, E.J.; Aguon, C.T.; Sy, A. Exploring Cultural and Age-Specific Preferences to Develop a Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention for CHamorus and Filipinos in Guam—Findings from a Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050746

Diaz TP, Camacho SG, Elmore EJ, Aguon CT, Sy A. Exploring Cultural and Age-Specific Preferences to Develop a Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention for CHamorus and Filipinos in Guam—Findings from a Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050746

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaz, Tressa P., Santino G. Camacho, Elizabeth J. Elmore, Corinth T. Aguon, and Angela Sy. 2025. "Exploring Cultural and Age-Specific Preferences to Develop a Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention for CHamorus and Filipinos in Guam—Findings from a Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050746

APA StyleDiaz, T. P., Camacho, S. G., Elmore, E. J., Aguon, C. T., & Sy, A. (2025). Exploring Cultural and Age-Specific Preferences to Develop a Community-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Intervention for CHamorus and Filipinos in Guam—Findings from a Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050746