Patterns of ICT Use and Technological Dependence in University Students from Spain and Japan: A Cross-Cultural Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Evaluation Method

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics Committee

3. Results

3.1. Perception of Academic Performance After the COVID-19 Pandemic

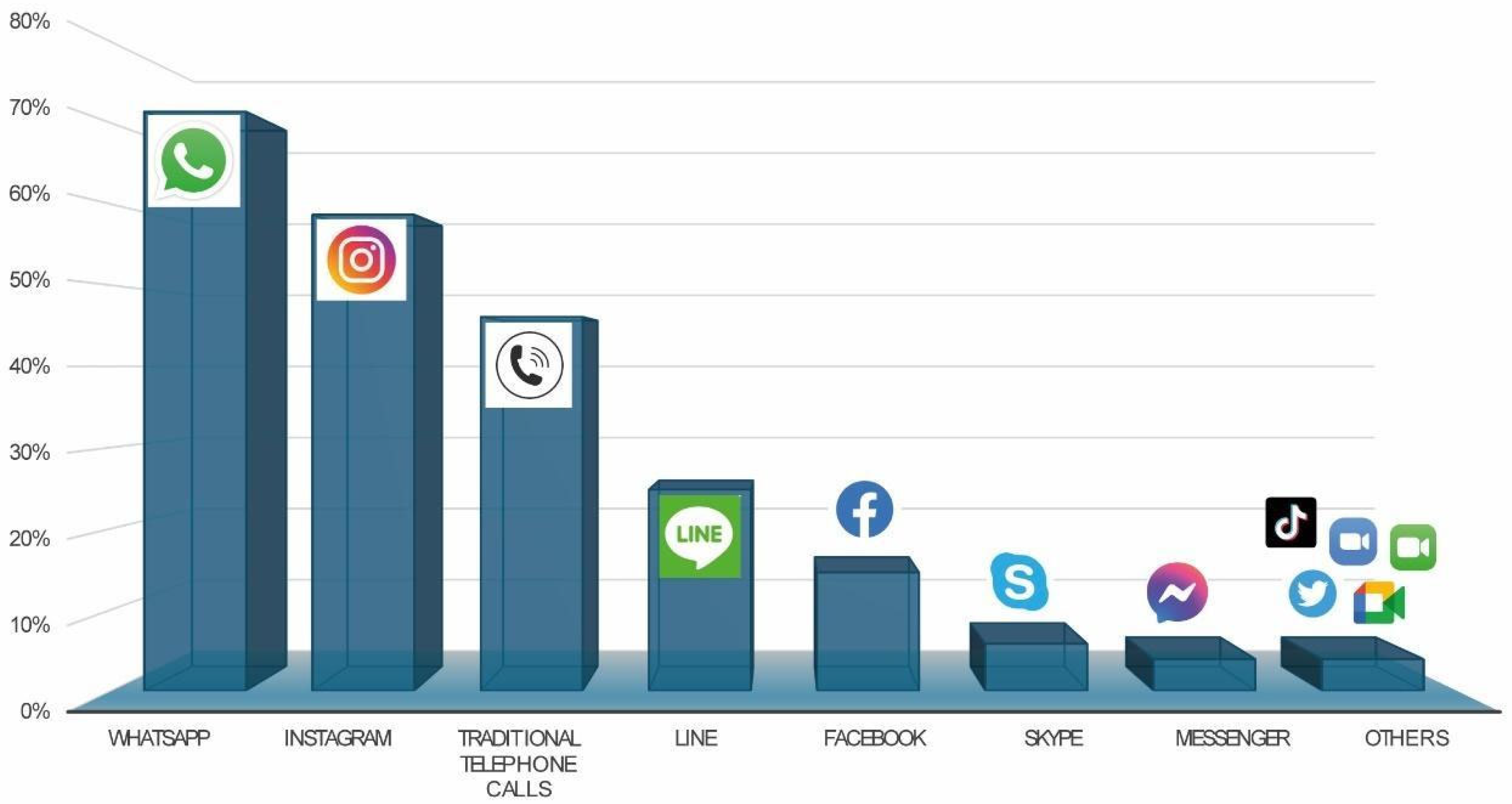

3.2. General Use of Information and Communication Technologies

3.3. Abusive Use of the Internet in Spanish and Japanese Universities

3.4. Abusive Use of Mobile Phones in Spanish and Japanese Universities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the dependence on ICTs in the lives of university students, raising the need to proactively address the potential negative effects of this increased exposure to technology. Negative impacts were observed on the academic performance of university students and their habits, suggesting the need to implement prevention and awareness strategies to encourage healthy use of technology.

- Significant increases have been reported in ICT addiction among young adults, with almost 30% being pathological internet users and 25.2% considered pathological mobile phone users.

- There is a clear association between excessive use of the internet and abusive use of mobile phones, with women being the most abusive users. Significant differences are evident in the use of ICT between men and women, which highlights the importance of considering gender approaches when designing interventions related to the use of ICTs in educational environments.

- Despite the adaptations in teaching during the pandemic, most participants (68.9%) did not perceive improvements in their academic performance, which suggests the need to review and adjust educational strategies in virtual environments.

- There are significant differences in the use of the internet and mobile phones between Spanish and Japanese students, which highlights the influence of cultural factors on technological dependence. These disparities can have an impact on the academic performance and mental health of young people.

- Increased use of ICTs during the pandemic has led to increased problematic use of the internet and mobile phones. These findings suggest the need to address ICT addiction and its potential consequences on mental health and academic performance.

5.1. Study Biases and Limitations

5.2. Implications of This Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martín Herrero, J.A. Bio-Psycho-Social Intervention in Addictions; McGraw Hill: Aula Magna, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brailovskaia, J. The «Vicious Circle of addictive Social Media Use and Mental Health» Model. Acta Psychol. 2024, 247, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Liu, J.; Bai, W.; Cao, T. Social pressures and their impact on smartphone use stickiness and use habit among adolescents. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Observatory of Drugs and Addictions. Report on Behavioral Disorders. Gambling with Money, Use of Video Games and Compulsive Use of the Internet in Surveys of Drugs and Other Addictions in Spain Ages and Studies; Ministry of Health, Government Delegation for the National Drug Plan: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- López-Fernández, O.; Honrubia-Serrano, M.L.; Freixa-Blanxart, M. Development and validation of the problematic use of new technologies (UPNT) questionnaire. Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- López-Fernández, O.; Honrubia-Serrano, M.; Freixa-Blanxart, M. Spanish adaptation of the “Mobile Phone Problem Use Scale” for the adolescent population. Addictions 2012, 24, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carbonell, X.; Fargues, M.B.; Rosell, M.C.; Lusar, A.C.; Oberst, U. Internet and mobile addiction: Fad or disorder? Addictions 2008, 20, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Montalvo, J.; López-Goñi, J.J. Addictions Without Drugs: Characteristics and Methods of Intervention; FOCAD. Continuing Distance Learning; General Council of Official Colleges of Psychologists: Madrid, Spain, 2010; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Arab, L.E.; Díaz, G.A. Impact of social networks and the internet on adolescence, positive and negative aspects. Las Condes Clin. Med. Mag. 2015, 26, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Salgado, P.; Rial Boubeta, A.; Braña Tobío, M.T.; Varela Mallou, J.; Barreiro Couto, C. Evaluation and early detection of problematic Internet use in adolescents. Psychothema 2014, 1, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chóliz, M. Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction 2010, 105, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeburúa, E.; Labrador, F.J.; Becoña, E. Addiction to New Technologies in Young People and Adolescents; Pyramid: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, A.; Phillips, J.G. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamibeppu, K.; Sugiura, H. Impact of the mobile phone on junior high-school students’ friendships in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, E.; Rodríguez, M.T.; Ruíz, J.M. Mobile phone addiction or abuse. Literature review. Addictions 2012, 24, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weare, K. What impact is having information technology on our young people’s health and well-being? Health Educ. 2004, 104, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Barkley, J.E.; Karpinski, A.C. The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of US college students. Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015573169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindell, D.R.; Bohlander, R.W. The use and abuse of cell phones and text messaging in the classroom: A survey of college students. Coll. Teach. 2012, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Hu, Z. COVID-19 lockdown stress and problematic social networking sites use among quarantined college students in China: A chain mediation model based on the stressor-strain-outcome framework. Addict. Behav. 2023, 146, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimadevilla, R.; Jenaro, C.; Flores, N. Impact of internet and mobile phone abuse on psychological health in a Spanish sample of high school students. Argent. J. Psychol. Clin. 2019, XXVIII, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, X.; Fúster, H.; Chamarro, A.; Oberst, U. Internet and mobile addiction: A review of Spanish empirical studies. Psychol. Pap. 2012, 33, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Gómez-Vela, M.; González-Gil, F.; Caballo, C. Problematic internet and cell-phone use: Psychological, behavioral, and health correlates. Addict. Res. Theory 2007, 15, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martínez, M.; Otero, A. Factors associated with cell phone use in adolescents in the community of Madrid (Spain). CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, A.; Golpe, S.; Gómez, P.; Barreiro, C. Variables associated with problematic Internet use among adolescents. Health Addict. 2015, 15, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Olivares, R.; Lucena, V.; Pino, M.J.; Herruzo, J. Analysis of behaviors related to the use/abuse of the Internet, mobile phone, shopping and gaming in university students. Addictions 2010, 22, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Villa, T.; Alguacil, J.; Almaraz, A.; Cancela, J.M.; Delgado, M.; García, M. Problematic Internet use in university students: Associated factors and gender differences. Addictions 2015, 27, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Abbouyi, S.; Bouazza, S.; El Kinany, S.; El Rhazi, K.; Zarrouq, B. Depression and anxiety and its association with problematic social media use in the MENA region: A systematic review. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2024, 60, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. Survey on Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Homes Year 2022. Press Releases. 2022; pp. 1–15. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/tich_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Touloupis, T.; Sofologi, M.; Tachmatzidis, D. Pattern of Facebook use by university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Relations with loneliness and resilience. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; Pan-American Medical: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp [Computer Software]: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- Kapahi, A.; Ling, C.; Ramadass, S.; Abdullah, N. Internet Addiction in Malaysia Causes and Effects. iBusiness 2013, 5, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrador, F.J.; Villadangos, S.M. Addiction to new technologies in adolescents and young people. In Addiction to New Technologies in Young People and Adolescents; Echeburúa, E., Labrador, F.J., Becoña, E., Eds.; Pyramid: Madrid, Spain, 2009; pp. 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Á.M.Ú.; Ferrandiz, D.A.; Valdecasas, B.F.G.; De la Cruz Campos, J.C. Comparative study on the use of new technologies between two Andalusian faculties of Education. Interuniversity magazine of teacher training. Contin. Old Norm. Sch. Mag. 2022, 36, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Su, L. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: Prevalence and psychological features. Child Care Health Dev. 2006, 33, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilt, J.A.; de Korniejczuk, R.B.; Collins, E. Internet addiction in Mexican university students. Univ. Res. J. 2015, 4, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T.; Peng, Z.W. Effect of pathological use of the internet on adolescent mental health: A prospective study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Calderón, G. Gender and internet addiction in Mexican university students. Sci. Future 2021, 11, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, M.; Brunelle, N.; Tremblay, J.; Leclerc, D.; Cousineau, M.M.; Khazaal, Y.; Légaré, A.A.; Rousseau, M.; Berbiche, D. Gender Difference in Internet Use and Internet Problems among Quebec High School Students. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.M.; Hwang, W.J. Gender Differences in Internet Addiction Associated with Psychological Health Indicators Among Adolescents Using a National Web-based Survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2014, 12, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, B.; Karthik, S.; Krushna, G.; Menon, V. Gender Variation in the Prevalence of Internet Addiction and Impact of Internet Addiction on Reaction Time and Heart Rate Variability in Medical College Students. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, CC01–CC04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, A.M.; Idemudia, E.S. Gender difference, class level and the role of internet addiction and loneliness on sexual compulsivity among secondary school students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2018, 23, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Ghazanfari, F.; Ebrahimzadeh, F.; Ghavi, S.; Badrizadeh, A. Investigate the relationship between cell-phone over-use scale with depression, anxiety and stress among university students. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, S.M.; Yee, A.; Ramachandran, V.; Sazlly Lim, S.M.; Wan Sulaiman, W.A.; Foo, Y.L.; Hoo, F.K. Validation of a Malay Version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale among Medical Students in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

| How much has your average monthly online spending increased since the start of the pandemic? | ||

| Between EUR 20 and EUR 50 (or the equivalent in your local currency) | 118 | 57.3% |

| Between EUR 51 and EUR 100 (or the equivalent in your local currency) | 31 | 15.0% |

| More than EUR 100 (or the equivalent in your local currency) | 8 | 3.9% |

| I do not make online purchases | 49 | 23.8% |

| Has the use of ICT changed your eating habits? | ||

| Yes, I eat more fast food or takeout | 25 | 12.1% |

| Yes, I eat more snacks, sweets, soft drinks, etc. | 14 | 6.8% |

| Yes, I eat healthier | 27 | 13.1% |

| No, I have the same eating habits | 140 | 68.0% |

| How many hours have you slept a day since the start of the pandemic? | ||

| More than 8 h | 29 | 14.1% |

| Between 7 and 8 h | 123 | 59.7% |

| Between 5 and 6 h | 48 | 23.3% |

| Less than 5 h | 6 | 2.9% |

| Never | Hardly Ever | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always | Always | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOS | n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % |

| item 1 | 32 | 15.5% | 63 | 30.6% | 76 | 36.9% | 18 | 8.7% | 11 | 5.3% | 6 | 2.9% |

| item 2 | 56 | 27.2% | 82 | 39.8% | 46 | 22.3% | 14 | 6.8% | 7 | 3.4% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 3 | 16 | 7.8% | 67 | 32.5% | 71 | 34.5% | 38 | 18.4% | 9 | 4.4% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 4 | 89 | 43.2% | 56 | 27.2% | 42 | 20.4% | 9 | 4.4% | 5 | 2.4% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 5 | 164 | 79.6% | 22 | 10.7% | 14 | 6.8% | 2 | 1.0% | 2 | 1.0% | 2 | 1.0% |

| item 6 | 63 | 30.6% | 61 | 29.6% | 49 | 23.8% | 19 | 9.2% | 8 | 3.9% | 6 | 2.9% |

| item 7 | 148 | 71.8% | 42 | 20.4% | 12 | 5.8% | 4 | 1.9% | - | - | - | - |

| item 8 | 52 | 25.2% | 49 | 23.8% | 68 | 33.0% | 17 | 8.3% | 15 | 7.3% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 9 | 80 | 38.8% | 40 | 19.4% | 54 | 26.2% | 18 | 8.7% | 9 | 4.4% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 10 | 64 | 31.1% | 57 | 27.7% | 53 | 25.7% | 19 | 9.2% | 9 | 4.4% | 4 | 1.9% |

| item 11 | 60 | 29.1% | 62 | 30.1% | 55 | 26.7% | 12 | 5.8% | 9 | 4.4% | 8 | 3.9% |

| item 12 | 120 | 58.3% | 64 | 31.1% | 17 | 8.3% | 2 | 1.0% | 2 | 1.0% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 13 | 170 | 82.5% | 26 | 12.6% | 9 | 4.4% | - | - | 1 | 0.5% | - | - |

| item 14 | 116 | 56.3% | 59 | 28.6% | 27 | 13.1% | 2 | 1.0% | 2 | 1.0% | - | - |

| item 15 | 118 | 57.3% | 46 | 22.3% | 34 | 16.5% | 6 | 2.9% | 2 | 1.0% | - | - |

| item 16 | 67 | 32.5% | 47 | 22.8% | 59 | 28.6% | 16 | 7.8% | 12 | 5.8% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 17 | 153 | 74.3% | 40 | 19.4% | 10 | 4.9% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 18 | 147 | 71.4% | 40 | 19.4% | 14 | 6.8% | 4 | 1.9% | 1 | 0.5% | - | - |

| item 19 | 19 | 9.2% | 17 | 8.3% | 73 | 35.4% | 42 | 20.4% | 41 | 19.9% | 14 | 6.8% |

| item 20 | 79 | 38.3% | 53 | 25.7% | 51 | 24.8% | 18 | 8.7% | 5 | 2.4% | - | - |

| item 21 | 28 | 13.6% | 37 | 18.0% | 59 | 28.6% | 41 | 19.9% | 29 | 14.1% | 12 | 5.8% |

| item 22 | 36 | 17.5% | 39 | 18.9% | 66 | 32.0% | 30 | 14.6% | 23 | 11.2% | 12 | 5.8% |

| item 23 | 82 | 39.8% | 56 | 27.2% | 50 | 24.3% | 9 | 4.4% | 7 | 3.4% | 2 | 1.0% |

| QUESTIONNAIRE | SEX | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | Japanese | Women | Man | ||||

| IOS | Light | n | 48 | 19 | 46 | 21 | 67 |

| % within IOS | 71.6% | 28.4% | 68.7% | 31.3% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 57.1% | 43.2% | 49.5% | 60.0% | 52.3% | ||

| Heavy | n | 36 | 25 | 47 | 14 | 61 | |

| % within IOS | 59.0% | 41.0% | 77.0% | 23.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 42.9% | 56.8% | 50.5% | 40.0% | 47.7% | ||

| Total | n | 84 | 44 | 93 | 35 | 128 | |

| % within IOS | 65.6% | 34.4% | 72.7% | 27.3% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Never | Hardly Ever | Sometimes | Often | Almost Always | Always | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COS | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| item 1 | 42 | 20.4% | 44 | 21.4% | 72 | 35.0% | 25 | 12.1% | 16 | 7.8% | 7 | 3.4% |

| item 2 | 71 | 34.5% | 77 | 37.4% | 47 | 22.8% | 9 | 4.4% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 3 | 37 | 18.0% | 77 | 37.4% | 62 | 30.1% | 22 | 10.7% | 4 | 1.9% | 4 | 1.9% |

| item 4 | 106 | 51.5% | 57 | 27.7% | 32 | 15.5% | 7 | 3.4% | 1 | 0.5% | 3 | 1.5% |

| item 5 | 159 | 77.2% | 34 | 16.5% | 8 | 3.9% | 3 | 1.5% | 2 | 1.0% | - | - |

| item 6 | 86 | 41.7% | 52 | 25.2% | 45 | 21.8% | 10 | 4.9% | 7 | 3.4% | 6 | 2.9% |

| item 7 | 148 | 71.8% | 42 | 20.4% | 12 | 5.8% | 3 | 1.5% | 1 | 0.5% | - | - |

| item 8 | 65 | 31.6% | 43 | 20.9% | 66 | 32.0% | 17 | 8.3% | 10 | 4.9% | 5 | 2.4% |

| item 9 | 90 | 43.7% | 49 | 23.8% | 37 | 18.0% | 17 | 8.3% | 10 | 4.9% | 3 | 1.5% |

| item 10 | 69 | 33.5% | 60 | 29.1% | 40 | 19.4% | 24 | 11.7% | 7 | 3.4% | 6 | 2.9% |

| item 11 | 78 | 37.9% | 64 | 31.1% | 40 | 19.4% | 14 | 6.8% | 4 | 1.9% | 6 | 2.9% |

| item 12 | 126 | 61.2% | 53 | 25.7% | 24 | 11.7% | 2 | 1.0% | 1 | 0.5% | - | - |

| item 13 | 169 | 82.0% | 27 | 13.1% | 8 | 3.9% | 2 | 1.0% | - | - | - | - |

| item 14 | 107 | 51.9% | 52 | 25.2% | 32 | 15.5% | 11 | 5.3% | 3 | 1.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 15 | 125 | 60.7% | 47 | 22.8% | 24 | 11.7% | 8 | 3.9% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 16 | 75 | 36.4% | 61 | 29.6% | 40 | 19.4% | 20 | 9.7% | 9 | 4.4% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 17 | 169 | 82.0% | 26 | 12.6% | 8 | 3.9% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 18 | 135 | 65.5% | 44 | 21.4% | 18 | 8.7% | 5 | 2.4% | 3 | 1.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 19 | 27 | 13.1% | 24 | 11.7% | 63 | 30.6% | 39 | 18.9% | 34 | 16.5% | 19 | 9.2% |

| item 20 | 73 | 35.4% | 54 | 26.2% | 57 | 27.7% | 18 | 8.7% | 3 | 1.5% | 1 | 0.5% |

| item 21 | 37 | 18.0% | 34 | 16.5% | 55 | 26.7% | 44 | 21.4% | 22 | 10.7% | 14 | 6.8% |

| item 22 | 37 | 18.0% | 46 | 22.3% | 65 | 31.6% | 30 | 14.6% | 17 | 8.3% | 11 | 5.3% |

| item 23 | 87 | 42.2% | 49 | 23.8% | 48 | 23.3% | 13 | 6.3% | 6 | 2.9% | 3 | 1.5% |

| QUESTIONNAIRE | SEX | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | Japanese | Women | Man | ||||

| IOS | Light | N | 35 | 18 | 36 | 17 | 53 |

| % within IOS | 66.0% | 34.0% | 67.9% | 32.1% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 48.6% | 54.5% | 45.6% | 65.4% | 50.5% | ||

| Heavy | N | 37 | 15 | 43 | 9 | 52 | |

| % within IOS | 71.2% | 28.8% | 82.7% | 17.3% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 51.4% | 45.5% | 54.4% | 34.6% | 49.5% | ||

| Total | N | 72 | 33 | 79 | 26 | 105 | |

| % within IOS | 68.6% | 31.4% | 75.2% | 24.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % within questionnaire or sex | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| COS CLASSIFICATION | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Heavy | ||||

| IOS CLASSIFICATION | Light | n | 38 | 0 | 38 |

| % within IOS | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within COS | 86.4% | 0.0% | 44.7% | ||

| % of the total | 44.7% | 0.0% | 44.7% | ||

| Heavy | n | 6 | 41 | 47 | |

| % within IOS | 12.8% | 87.2% | 100.0% | ||

| % within COS | 13.6% | 100.0% | 55.3% | ||

| % of the total | 7.1% | 48.2% | 55.3% | ||

| Total | n | 79 | 26 | 105 | |

| % within IOS | 51.8% | 48.2% | 100.0% | ||

| % within COS | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % of the total | 51.8% | 48.2% | 100.0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín Herrero, J.A.; Torres García, A.V.; Vega-Hernández, M.C.; Iglesias Carrera, M.; Kubo, M. Patterns of ICT Use and Technological Dependence in University Students from Spain and Japan: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050737

Martín Herrero JA, Torres García AV, Vega-Hernández MC, Iglesias Carrera M, Kubo M. Patterns of ICT Use and Technological Dependence in University Students from Spain and Japan: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050737

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín Herrero, José Antonio, Ana Victoria Torres García, María Concepción Vega-Hernández, Marcos Iglesias Carrera, and Masako Kubo. 2025. "Patterns of ICT Use and Technological Dependence in University Students from Spain and Japan: A Cross-Cultural Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050737

APA StyleMartín Herrero, J. A., Torres García, A. V., Vega-Hernández, M. C., Iglesias Carrera, M., & Kubo, M. (2025). Patterns of ICT Use and Technological Dependence in University Students from Spain and Japan: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050737