A University’s Role in Developing a Regional Network of Dementia Friendly Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Dementia Care and Stigma Concerns

1.2. The Importance of Community Engagement

1.2.1. Dementia Friendly America

1.2.2. A University’s Role

1.3. The Current Project/Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Network Development

Description of Participating Communities

2.2. Retrospective Evaluation Methods

3. Results

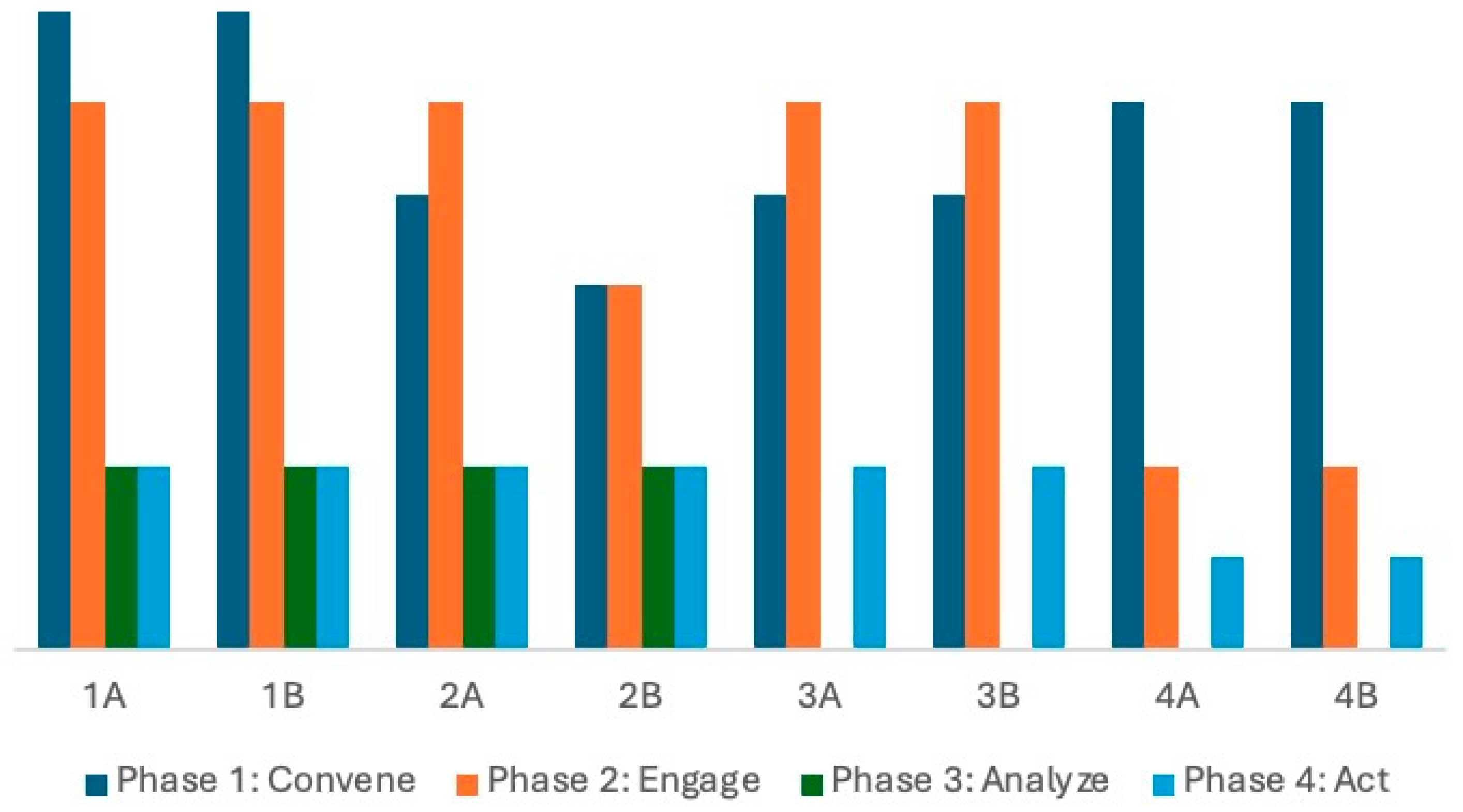

3.1. Adherence to the DFC Community Change Process

3.1.1. Phase One: Convene

3.1.2. Phase Two: Engage

3.1.3. Phase Three: Analyze

| Cohort and Community Identifier | DFA Community Engagement Tool | BKAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sectors | Participants | Sectors | Participants | |

| 1A | 3 | 9 | 7 | 27 |

| 1B | 4 | 14 | 8 | 35 |

| 2A | 1 | 1 | 6 | 21 |

| 2B | 3 | 18 | 5 | 12 |

| 3A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

3.1.4. Phase Four: Act

3.2. Adherence to DFC Guiding Principles

3.2.1. Principle One

3.2.2. Principle Two

3.3. Alignment with National DFC Efforts

- Increase awareness and understanding of dementia and PLWD

- Address the changing needs of PLWD and care partners.

- Increase awareness and understanding of brain health and risk reduction

- Improve the physical environment in public places.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Calls for Urgent Transformation of Care and Support Systems for Older People. 1 October 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-10-2024-who-calls-for-urgent-transformation-of-care-and-support-systems-for-older-people (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- United Nations. Progress Report on the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing, 2021–2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240079694 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Giblin, J.C. Successful aging: Choosing wisdom over despair. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2011, 49, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noriega, C.; Velasco, C.; López, J. Perceptions of grandparents’ generativity and personal growth in supplementary care providers of middle-aged grandchildren. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 37, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badache, A.C.; Hachem, H.; Mäki-Torkko, E. The perspectives of successful ageing among older adults aged 75+: A systematic review with a narrative synthesis of mixed studies. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 1203–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, L.; Hall, D.; Cridland, E.; Fleming, R.; Brennan-Horley, C.; Guggisberg, N.; Frost, D.; Hasan, H. Involvement of people with dementia in raising awareness and changing attitudes in a Dementia Friendly Community pilot project. Dementia 2019, 18, 2679–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafighi, K.; Villeneuve, S.; Rosa Neto, P.; Badhwar, A.; Poirier, J.; Sharma, V.; Medina, Y.I.; Silveira, P.P.; Dube, L.; Glahn, D.; et al. Social isolation is linked to classical risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Towards a Dementia-Inclusive Society: WHO Toolkit for Dementia-Friendly Initiatives (DFIs); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Sideman, A.B.; Al-Rousan, T.; Tsoy, E.; Escudero, S.D.P.; Pintado-Caipa, M.; Kanjanapong, S.; Mbakile-Mahlanza, L.; De Oliveira, M.O.; De La Cruz-Puebla, M.; Zygouris, S.; et al. Facilitators and barriers to dementia assessment and diagnosis: Perspectives from dementia experts within a global health context. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 769360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; White, E.M.; Mills, C.; Thomas, K.S.; Jutkowitz, E. Rural-urban differences in diagnostic incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, A.; Smith, J.; Taylor, R. Dementia-friendly initiatives for individuals living with dementia, care partners, and communities. J. Dement. Care 2023, 47, 1–11. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48749041 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kramarow, E.A. Diagnosed Dementia in Adults Age 65 and Older: United States CDC 2022 Data. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr203.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Dhana, K.; Beck, T.; Desai, P.; Wilson, R.S.; Evans, D.A.; Rajan, K.B. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease dementia in the 50 US states and 3142 counties: A population estimate using the 2020 bridged-race postcensal from the National Center for Health Statistics. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 4388–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.R.; Kulibert, D.; McFadden, S.H. Effects of dementia knowledge and dementia fear on comfort with people having dementia: Implications for dementia-friendly communities. Dementia 2020, 19, 2542–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Shen, D.; Gao, J.; Li, Z.; Lv, Y.; Shi, X.; Mao, C. Analysis of changes in social isolation, loneliness, or both, and subsequent cognitive function among older adults: Findings from a nationwide cohort study. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 5674–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, P.; Young, C.B.; Ezeh, C.; Lacayo, B.; Seblova, D.; Andrews, R.M.; Gibbons, L.; Kraal, A.Z.; Turney, I.; Deters, K.D.; et al. Loneliness, cerebrovascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and cognition. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 7113–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. It’s Time to Harness the Power of Connection for Our Health and Well-Being. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/it-s-time-to-harness-the-power-of-connection-for-our-health-and-well-being (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Waldinger, R.J.; Schulz, M.S. What’s love got to do with it? Social functioning, perceived health, and daily happiness in married octogenarians. Psychol. Aging 2010, 25, 422–431. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2896234/ (accessed on 20 January 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 123–145. Available online: https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Sari, D.W.; Igarashi, A.; Takaoka, M.; Yamahana, R.; Noguchi-Watanabe, M.; Teramoto, C.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Virtual reality program to develop dementia-friendly communities in Japan. Australas. J. Ageing 2020, 39, e352–e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, C.D.; Robinson, M.T.; Willis, F.B.; Albertie, M.L.; Wainwright, J.D.; Fudge, M.R.; Parfitt, F.C.; Lucas, J.A. Creating a Dementia Friendly Community in an African American neighborhood: Perspectives of people living with dementia, care partners, stakeholders, and community residents. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, R.; Bennett, K.; Preece, T.; Phillipson, L. The development and testing of the Dementia Friendly Communities environment assessment tool (DFC EAT). Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 29, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersma, E.C.; Denton, A. From social network to safety net: Dementia-friendly communities in rural northern Ontario. Dementia 2016, 15, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.H. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Harrison, K.L.; Ritchie, C.S.; Patel, K.; Hunt, L.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Yaffe, K.; Smith, A.K. Care settings and clinical characteristics of older adults with moderately severe dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, C.J.; Somerville, C.; Greenfield, E.A.; Coyle, C. Organizational characteristics of senior centers and engagement in Dementia Friendly Communities. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, igad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, C.; Inagaki, H.; Sugiyama, M.; Miyamae, F.; Edahiro, A.; Ito, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Sasai, H.; Okamura, T.; Hirano, H.; et al. A neighbour to consult with is important in dementia-friendly communities: Associated factors of self-efficacy allowing older adults to continue living alone in community settings. Psychogeriatrics 2024, 24, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathie, E.; Antony, A.; Killett, A.; Darlington, N.; Buckner, S.; Lafortune, L.; Mayrhofer, A.; Dickinson, A.; Woodward, M.; Goodman, C. Dementia-friendly communities: The involvement of people living with dementia. Dementia 2022, 21, 1250–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, L.; Hudson, A.; Gregorio, M.; Jackson, L.; Mann, J.; Horne, N.; Berndt, A.; Wallsworth, C.; Wong, L.; Phinney, A. Creating Dementia-Friendly Communities for social inclusion: A scoping review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211013596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dementia Friendly America. Overview—Dementia Friendly America. Available online: https://dfamerica.org/overview/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- ACT on Alzheimer’s. Dementia Friendly Communities Toolkit. Available online: https://www.actonalz.org/dementia-friendly-toolkit (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Novak, L.; Horne, E.; Brackett, J.; Meyer, K.; Ajtai, R. Dementia Friendly Communities: A Review of current literature and reflections on implementation. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2020, 9, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, A.; Mansor, N.N.A. Sustainability of community engagement—In the hands of stakeholders? Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chung, J.E.; Li, J.; Robinson, B.; Gonzalez, F. A case study of community—Academic partnership in improving the quality of life for asthmatic urban minority children in low-income households. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medved, P.; Ursic, M. The benefits of university collaboration within university-community partnerships in Europe. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2021, 25, 79, eISSN 2164–8212. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.W.; Jumper-Thurman, P.; Plested, B.A.; Oetting, E.R.; Swanson, L. Community Readiness: Research to Practice. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, A.; Meza, R.D.; Brikho, B.; Naaf, M.; Estabillo, J.A.; Gomez, E.D.; Vejnoska, S.F.; Dufek, S.; Stahmer, A.C.; Aarons, G.A. Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q. 2016, 94, 163–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, A.; Hasche, L.; Talamantes, M.; Bernhardt, M. The impact of intergenerational engagement on social work students’ attitudes toward aging: The example of Clermont College. Health Soc. Work 2020, 45, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fields, N.L.; Cassidy, J.; Daniel, K.M.; Cipher, D.J.; Troutman, B.A. Attitudes toward aging among college students: Results from an intergenerational reminiscence project. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 538. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10376671/pdf/behavsci-13-00538.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ehlman, M.C.; Nimkar, S.; Nolan, B.; Thomas, P.; Caballero, C.; Snow, T. Health Workers’ Knowledge and Perceptions on Dementia in Skilled Nursing Homes: A Pilot Implementation of Teepa Snow’s Positive Approach to Care Certification Course. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2018, 38, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Art Is In”—A Professionally Curated Art Program for Patients and Care Partners at Home: The Memory Center at The University of Chicago Medicine. Available online: https://thememorycenter.uchicago.edu/artisin/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- What Is a Dementia-Friendly Campus—And How Do We Create That? Human Resources. 14 August 2023. Available online: https://hr.wisc.edu/blog/what-is-a-dementia-friendly-campus-and-how-do-we-create-that/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Scher, C.; Greenfield, E.A. Dementia-Friendly Community Initiatives: Voices from Practice Leaders in Massachusetts. Available online: https://socialwork.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/2023-03/Dementia-Friendly%20Report%20FINAL%2003.04.22.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Dementia Friendly Iowa: Supporting Dementia Friendliness in Iowa. Available online: https://dementiafriendlyiowa.org/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- DEER Program. Welcome to Dementia Friendly Nevada. DEER Program 2025. January 7. Available online: https://deerprogram.org/dementia-friendly-nevada/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Wiese, L.K.; Williams, C.L.; Tappen, R.M.; Newman, D. An updated measure for investigating basic knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease in underserved rural settings. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 24, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dementia Friendly America. DFA Community Toolkit—Dementia Friendly America. Available online: https://dfamerica.org/community-toolkit/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Oetting, E.R.; Plested, B.A.; Edwards, R.W.; Thurman, P.J.; Kelly, K.J.; Beauvais, F.; Stanley, L.R. Community readiness for community change. In Tri-Ethnic Center Community Readiness Handbook, 2nd ed.; Sage Hall, Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2014; Available online: https://tec.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CR_Handbook_8-3-15.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kehl, M.; Brew-Sam, N.; Strobl, H.; Tittlbach, S.; Loss, J. Evaluation of community readiness for change prior to a participatory physical activity intervention in Germany. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, ii40–ii52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, P.J.; Plested, B.A.; Edwards, R.W.; Foley, R.; Burnside, M. Community readiness: The journey to community healing. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2003, 35, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilenski, S.M.; Greenberg, M.T.; Feinberg, M.E. Community readiness as a multidimensional construct. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 35, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Planning for Health Assessment: Frameworks & Tools | Public Health Gateway | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/public-health-strategy/public-health-strategies-for-community-health-assessment-models-frameworks-tools.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Breitenstein, S.M.; Gross, D.; Garvey, C.A.; Hill, C.; Fogg, L.; Resnick, B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Hu, J.; Weiss, J.; Knopman, D.S.; Albert, M.; Windham, B.G.; Walker, K.A.; Sharrett, A.R.; Gottesman, R.F.; Lutsey, P.L.; et al. Lifetime risk and projected burden of dementia. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohort and Community Identifier | Date of DFC Designation | Population Density * | Medical Designation * | Original Geographic Scope | Sector Represented by the DFC Coordinator ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | January 2021 | Rural | MUA | Town | AAA |

| 1B | January 2021 | Rural | MUA | Town | AAA |

| 2A | February 2022 | Rural | MUA | Town | LTC |

| 2B | December 2021 | Urban | Not MUA | Neighborhood | University |

| 3A | October 2022 | Urban | Mixed | Neighborhood | LTC |

| 3B | December 2022 | Urban | Not MUA | County | LTC |

| 4A | November 2023 | Rural | Not MUA | County | LTC |

| 4B | May 2024 | Mixed | Mixed | County | LTC |

| DFA Model Step | Key GWEP DFC Activities | University Technical Support |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Convene key community leaders and members, known as an action team, to understand dementia effects |

|

|

| Step 2: Engage key leaders to conduct a community assessment of the factors supportive of PLWD and those that are barriers |

|

|

| Step 3: Analyze assessment results to determine stakeholder issues and set community goals |

|

|

| Step 4: Create a community action plan that includes specific objectives, activities, leadership, and timelines |

|

|

| DFC | PLWD Representation | Caregiver Representation |

|---|---|---|

| 1A | 1 | 1 |

| 1B | 1 | 2 |

| 2A | 0 | 0 |

| 2B | 0 | 1 |

| 3A | 0 | 0 |

| 3B | 0 | 0 |

| 4A | 0 | 0 |

| 4B | 0 | 3 |

| Community Identifier | Number of Action Team Members | Number of Sectors Represented | Geographic Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 17 | 6 | County |

| 1B | 11 | 6 | County |

| 2A | 11 | 4 | City |

| 2B | 6 | 2 | (Merged with 3A) |

| 3A | 11 | 5 | County |

| 3B | 13 | 5 | County |

| 4A | 14 | 4 | County |

| 4B | 8 | 3 | County |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Standiford Reyes, L.; Ehlman, M.C.; Leahy, S.; Lawrence, R. A University’s Role in Developing a Regional Network of Dementia Friendly Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050721

Standiford Reyes L, Ehlman MC, Leahy S, Lawrence R. A University’s Role in Developing a Regional Network of Dementia Friendly Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050721

Chicago/Turabian StyleStandiford Reyes, Laurel, M. C. Ehlman, Suzanne Leahy, and Reagan Lawrence. 2025. "A University’s Role in Developing a Regional Network of Dementia Friendly Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050721

APA StyleStandiford Reyes, L., Ehlman, M. C., Leahy, S., & Lawrence, R. (2025). A University’s Role in Developing a Regional Network of Dementia Friendly Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050721