Learn to Live Again: A Pilot Study to Support Women Experiencing Domestic Violence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

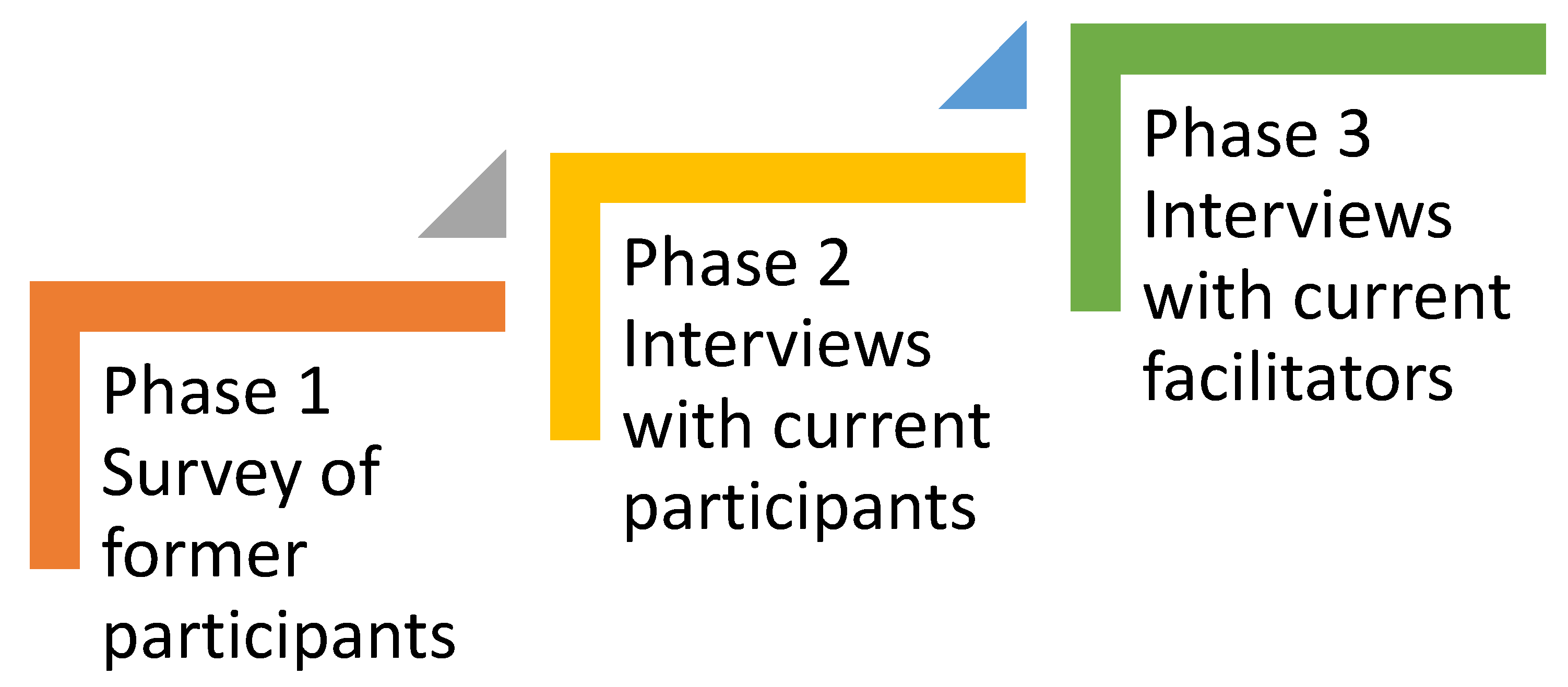

2.1. Study Design

- Data Collection: Gathering quantitative and qualitative data from various sources, such as surveys, interviews, and performance metrics.

- Analysis: Assessing the data to understand how well the pilot program met its objectives and identifying any challenges or successes.

- Feedback: Using the insights gained to make informed decisions about the program’s future, including potential adjustments or broader implementation.

2.2. Study Recruitment

2.3. Study Data Collection

2.4. Study Analysis

2.5. Study Ethics

2.6. Study Intervention

“Please persevere and keep going, this group will change your entire mindset and allow you to be able to live again, to be happy and feel safe, because you deserve to be free, and you are worthy of happiness”.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

- “I felt supported in a safe environment”;

- “The more knowledge I had I felt stronger in myself”;

- “Learning new things”;

- “The opportunity to recover and regain my self worth”;

- “It had a lot of helpful information for learning to live again”.

“I was going through a horrible separation which saw myself and my children live in refuges as my children’s father sold our family home leaving us homeless. I was referred to Barnardos by one of the caseworkers I was working with as they believed I would benefit from the program.”

“I needed to continue my life after leaving my husband and be able to talk to other women from domestic violence situations. I needed to be happy again.”

- n = 24 women found the program beneficial.

- n = 18 women reported the program delivery structure including group size, group duration, topics, and activities were appropriate.

- n = 13 women rated their overall experience as very good or excellent.

- n = 11 women reported a strong level of engagement in the program and rated their engagement as ‘very’ engaged.

- n = 7 reported the program met their expectations.

3.2. Interview Results

L2LA Participants

3.3. “Get Some Light on Everything”

3.3.1. Making Connections

“It is a really special group because we were around people who have experienced similar things, and it definitely made you feel better and more confident in sharing some of the things you had been through”(Participant 6).

“The support is the biggest word like the sense of community and support that were in it together and that we are here as a team, it was a team environment it wasn’t like I was just a customer taking what I wanted, like I felt like I was there to contribute just as much as I’d like to receive.”(Participant 2—Online)

“to hear some of the stuff that they had been through, even though I had gone through almost the same, for some things in particular, hearing it come from somebody else, gives you a different kind of empathy to reflect on yourself.”(Participant 1—Online)

3.3.2. Providing a Safe and Nurturing Environment

“It was nice to come into such a positive and nurturing environment where everyone was so connected, it was something I looked forward to coming to”(Participant 6).

“I feel like it was a part of learning to know that I could deserve such a nice thing”(Participant 5).

“…it really helps when you’re stuck in a mindset, and someone will say something or bring it out in a different way and change the way you think about it”(Participant 3).

“…I felt really validated as well that I could share stuff that had happened, and they could stand up and be like yeah that’s shit, that’s not how life is meant to be and how I feel is similar”(Participant 2 Online).

3.3.3. Facilitators’ Connection with Women

“I never got rushed or hurried when I was having particularly bad weeks when I just wanted to talk about stuff. They always had time for me and others to offload whatever we had to talk about during that week. It was always enough time to hear us out and listen”(Participant 2).

“I feel these women are amazing and the way they can gently prompt us to grow and heal is so clever and it’s such a different approach. It sets the body up for long-term healing, it’s planting so many seeds and you take that with you for life”(Participant 5).

“…what you need when you are going through what we have gone through”(Participant 2).

3.4. “Came Together as a Perfect Puzzle”

3.4.1. Practical Activities

“We did a really good exercise where we had to pick up a rock and throw that and get rid of something we were holding onto; I suppose when you put in into something physical rather than thinking about it in your mind or doing something physically to get that out, I think it really helps”(Participant 3).

“I really liked when we spoke about our emotions/feelings and how to control them.”(Participant 1)

“…those tangible things that we were given, were really helpful in visualising things in our lives”(Participant 1 Online).

“I already knew I was pouring from an empty cup, but until you see it with the water, you don’t, it wasn’t as obvious to me until them… it was a bit sad coming to terms that there wasn’t anyone to put in my jar”(Participant 1 Online).

3.4.2. Self-Care

“Now, I wake up every morning and I try to give myself at least 10 min of meditation…it’s been super beneficial for my day not being so stressful… like I thought I was doing all the right things but after that course I could actually spoke to my friend and said I feel like I woke up, I’m actually me again”(Participant 2 Online).

“The ladies would always try to pamper us you know even just making us a cup of tea that was really nice like you felt really important”(Participant 2).

3.4.3. Accessibility

“I wouldn’t have had access to the face-to-face version so I would have completely missed out on the whole thing, and it’s completely changed the way that I, it’s just really had a profound impact on my life”.

“I was able to have the kids in the other room whilst I was in the group, I didn’t have to stress about finding a babysitter for the kids, which would have been a difficulty an prevented me from engaging in the program if I was in a face-to-face group”(Participant 1 Online).

“I wish it was easier for me with my kids, I have been given every opportunity with the childminder here, but I think with my kids being so clingy and attached to my hip it can be a bit distracting as I am not able to fully focus”(Participant 5).

3.5. “Moving on and Moving Forward”

3.5.1. Improving Wellbeing and Healing

“Given such an invaluable opportunity to be a part of something like this. I felt very lucky to be here and I saw it as a great opportunity to move forward for me and my kids”(Participant 5).

“I feel there are not enough support services to access out in the community that are like this one”(Participant 6).

3.5.2. Recommending L2LA

“I would definitely recommend to any person experiencing domestic violence whether in their past, present, or future because I came out with such valuable skills and tools that I can use and very simple ones too that I can use going forward”(Participant 2).

“I genuinely really want to make a difference and am because I’m kind of on the other side, I am a kind of a strong woman and the shit that I have gone through is really messed up… I’m safe now and I know I am completely safe now. So, for them to see me having a positive life as well”(Participant 2 Online).

3.6. Differences Between Online and Face-to-Face Programs

3.6.1. Scheduling of L2LA

“…at first I thought it was too long 3–4 h but I think I enjoyed it that much and I got that much out of it that I felt we could have gone longer”(Participant 6).

“Like this obviously had a really big impact on, but I think that there could’ve had been even a bit more time to share around our mutual sessions. So, at the end of session because each session only goes for half an hour”(Participant 2 Online).

3.6.2. Concerns

“When you talk over the phone at the same time, like in person we can talk at the same time, and you know who’s talking and like with this you sort of have to hold yourself and some things are missed being said because you’re waiting”(Participant 2 Online).

3.7. Facilitators

3.8. “Sitting in the Space”

3.8.1. Creating Safe Spaces

“We want them to turn up because even sitting within the space allows us to create safety and supports them… We don’t force them to do any activity because obviously, that’s the circumstance they’ve come from”(Facilitator 3).

“It is more around hopes that they feel a sense of connection and the hope is that the facilities are able to create a safe space where there’s some space for healing and that at the end of it, the participants have some strategies that will support them.”(Facilitator 1).

“…we want everything to be about their own choice and own power in the information and messengers that they are getting and receiving and giving as well…if they want to come, they can answer, they can talk when they want to, they don’t have to…”(Facilitator 1 Online).

“… if someone starts talking about a recent incident of violence and we know that that’s going to be a massive trigger probably for the whole group, how we then allow her to tell her story, but then safely wrap it back up and reflect it on the issues is a challenge”(Facilitator 3).

“The most challenging components of facilitating is managing a range of trauma and managing the different dynamics of women. We often get a few that are big talkers and others are more introverted so finding the space for everyone to share if there are those powerful personalities is definitely one of the challenging parts of facilitating”(Facilitator 2).

3.8.2. Supporting Women to Support Children

“Lots of the groups in the Illawarra don’t offer childcare that runs alongside it. So, one of the things that we’ve tried really hard to do, even though we have no money is to use one of our other workers from our programs for childcare to be with the children in the adjoining space because it’s more that the women are likely to attend if they can be safe and together with their child”(Facilitator 3).

“I would prefer it to be more of like that Theraplay style of stuff supporting the children rather than calling it childcare. So, when mum comes in and she’s really like anxious or having really overwhelming fear feelings. Then what we’re saying from the worker that’s sitting with the children is that the children are reflecting that.”(Facilitator 3).

“… it was when kids would want to come in and out of the room… it was a challenge in terms of how that mum was then able to express herself, speak freely, and how the other women may have felt comfortable speaking with the children there”(Facilitator 4).

3.8.3. Being Flexible

“What I think worked really well was how adaptable the program can be, so we had our plans or rough guideline of what each week was meant to be about, but it was very tailored to the group and where they were at on that particular day.”(Facilitator 4).

“…it’s so easy to reach people in an online format, you know I can run this program anywhere, from anywhere to anyone anywhere, so I think it is an amazing way being able to deliver it”(Facilitator 2 Online).

“…some women may not have their children in their care anymore and in week 7 we do a letter to your child so that might be quite triggering so we might not do that or adapt that”(Facilitator 2).

3.8.4. Enhancing Wellbeing

“My favourite week is Rock Week. I like Rock Week because it’s one of the ones where they get to do lots of weighted activities. So, we use really heavy rocks and channel emotions and energy into these rocks and the women get to say whatever they want to these rocks, and they absolutely launch them outside”(Facilitator 3).

“… the toolbox is like a list or a tonne of little activities or experiences that you use throughout the eight weeks of the program, but it is not specifically scripted into a week”(Facilitator 3).

“…women were talking about how I don’t really know what love is and loves shit and loves this and loves that, so we go ok, the heart toolbox. So we go into our toolbox as facilitators and then we say to them, can you draw a heart and then we get them to on their page of their journal and we say put on the inside of your heart after so many weeks, what you think is actually love. And then on the outside, what you thought was love or what that person perceived to give you as love when it’s actually not”(Facilitator 3).

“…essential oil they could put on before they did the group, the little chocolate, the cup of tea or the coffee…which enriches the experience if it feels personalised for them and just you know, having it so easy to just grab what week you’re in”(Facilitator 2).

3.9. Processes

3.9.1. Pre-Group Interviews

“… we do the pre-group interview so we understand their trauma and it makes us aware of potential triggers that there might be”(Facilitator 2).

“We offer a space where they can fall out to if they need time out to process something and then one of the facilitators has done the pre-group interview, so we know whether or not that person needs to be followed to that safe space within that moment or if you give them 5–10 min and then go in and check”(Facilitator 3).

“… that is what part of the pre-interview is to identify but there’s always an element of risk or things can change for them along the way”(Facilitator 1).

“We are really checking in as we go along, we’re not leaving it straight away till the end, so that builds some rapport for the group even though it’s quite refined”(Facilitator 1 Online).

3.9.2. Post-Referral Process

“We do try really hard to make sure if they haven’t already got another support in place that they do that during the group, so that when it is over they are moving into something else, and we are not just kind of leaving them. Or we refer them onto one of our other groups like a parenting group”(Facilitator 4).

3.9.3. Facilitator Debrief

“It was really important for the facilitators to debrief each week and have some space after the group. We definitely need to debrief and get together to plan for the next week given what had happened in that particular week. Having the time to do that is vital”(Facilitator 1).

“…if there is anything that came up for either of us, we discuss it in that space and if needs be we follow up with our manager. We are quite mindful of having that time after so you are not carrying their trauma with you, and you can offload together and move on”(Facilitator 2).

3.9.4. Program Scheduling

“Most women would like it to run longer than eight weeks and it is sad when it ends but eight weeks feels long enough, we get through a lot of material in that time and I don’t think we need it to be any longer and I don’t think it can be any shorter because some women need that amount of time to build confidence in the people around them and trust to share and begin to do that healing”(Facilitator 2).

“We do it from 10:30-1 because it allows them to not be rushed in the morning and get to the venue on time. We also try to do it within a 10 or 11-week term but not starting week one of the term … so that if women have children in school or going to childcare that they can still get their kids to school”(Facilitator 3).

“Thirty minutes for a group program is a really small amount of time, once you check in with everyone, once we you know allow them to have a discussion after the weekly activity occurred… it did not feel long enough. The women were pretty good to go over a lot of the time, which we needed, just to allow for them to have space to speak about their experiences”(Facilitator 2 Online).

3.9.5. Safety Planning

“We didn’t know if the perpetrator would be within the home environment with them, when these calls were taking place… generally with the technology and the phone use, the calls can be deleted, taken off when they are checking their phone. But generally, if the perpetrator has access to their technology, they can usually see, whether it be their emails, or logging into Facebook if they doing a meeting that way…”(Facilitator 1 Online).

“I had to talk to her about that and how it was not ok for her to keep coming back to the group as it would have been quite damaging for the other women”(Facilitator 1).

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Respect Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety, Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/personal-safety-australia/2021-22 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Potter, C.; Morris, R.; Hegarty, K.; García-Moreno, C.; Feder, G. Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, A. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia: Continuing the National Story 2019; AIHW: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2019.

- Karakurt, G.; Smith, D.; Whiting, J. Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Mental Health. J. Fam. Violence 2014, 29, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedovskiy, K.; Higgins, S.; Paranjape, A. Intimate Partner Violence: How Does it Impact Major Depressive Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder among Immigrant Latinas. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2008, 10, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, E.; Kaltman, S.; Goodman, L.; Dutton, M. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. J. Trauma. Stress 2008, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, A. The Choice: Violence or Poverty; University of Technology Sydney: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krigel, K.; Benjamin, O. Women working in the shadow of violence: Studying the temporality of work and violence embeddedness (WAVE). Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2021, 84, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; McGiffert, M.; Fusco, R.; Kulkarni, S. “The Propellers of My Life” The Impact of Domestic Violence Transitional Housing on Parents and Children. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2023, 40, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Feder, G. Help-seeking amongst women survivors of domestic violence: A qualitative study of pathways towards formal and informal support. Health Expect 2016, 19, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, L.; Toone, E.; Wendt, S.; Taft, A.; Humphreys, C. Recover—Reconnecting Mothers and Children After Family Violence: The Child–Parent Psychotherapy Pilot; ANROWS: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.; Chami, G.; Udit, A. A Study on How Domestic Violence Impacts on the Physical, Psychological, and Financial Conditions of Women and Children in Trinidad and Tobago. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work. 2021, 7, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Van Ee, E. Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, M. Children’s Exposure to Domestic and Family Violence—Key Issues and Responses; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015.

- Campo, M. Domestic and Family Violence in Pregnancy and Early Parenthood—Overview and Emerging Interventions; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015.

- Korab-Chandler, E.; Kyei-Onanjiri, M.; Cameron, J.; Hegarty, K.; Tarzia, L. Women’s experiences and expectations of intimate partner abuse disclosure and identification in healthcare settings: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naismith, I.; Ripoll, K.; Pardo, V. Group Compassion-Based Therapy for Female Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence and Gender-Based Violence: A Pilot Study. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutty, L.; Babins-Wagner, R.; Rothery, M. Women in IPV Treatment for Abusers and Women in IPV Survivor Groups: Different or Two Sides of the Same Coin? J. Fam. Violence 2017, 32, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.; Robertson, E.; Patin, G. Improving Emotional and Cognitive Outcomes for Domestic Violence Survivors: The Impact of Shelter Stay and Self-Compassion Support Groups. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP598–NP624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, N.; Cameron, J.; Baloch, S.; Tarzia, L.; Hegarty, K. Health practitioners’ perceptions of structural barriers to the identification of intimate partner violence: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoebotham, A.; Coulson, N. Therapeutic Affordances of Online Support Group Use in Women with Endometriosis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e109/1–e109/11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Matos, M.; Machado, A. Effectiveness of a Group Intervention Program for Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Small Group Res. 2017, 48, 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, L.; Driessen, M.; Lewis-Dmello, A. An Evaluation of a Parent Group for Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, N.; Fitz-Gibbon, K.; Meyer, S. Responding to women experiencing domestic and family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring experiences and impacts of remote service delivery in Australia. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2022, 27, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndungu, J.; Ngcobo-Sithole, M.; Gibbs, A. Learners’ viewpoints on the possibilities and limitations imposed by social contexts on online group-based participatory interventions to address violence. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 3894–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, E.; Knyahnytska, Y.; Omrani, M.; Nikjoo, N.; Stephenson, C.; Layzell, G.; Simpson, A.; Alavi, N. Benefits of Digital Mental Health Care Interventions for Correctional Workers and Other Public Safety Personnel: A Narrative Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 921527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, L.; von Gruner, C.; Zhang, X.; Margraf, J.; Totzeck, C. Positive Emotions Training (PoET) as an online intervention to improve mental health: A feasibility study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webelhorst, C.; Jepsen, L.; Rummel-Kluge, C. Utilization of e-mental-health and online self-management interventions of patients with mental disorders—A cross-sectional analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; McDonnell, D.; Chen, H.; Ahmad, J.; Šegalo, S.; Da Veiga, C. Technology-Based Mental Health Interventions for Domestic Violence Victims Amid COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health Pilot Studies: Common Uses and Misuses. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/grants/pilot-studies-common-uses-and-misuses (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- CDC Approach to Program Evaluation. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/evaluation/php/about/index.html (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumivero. NVivo 12; Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, P.; Kline, M.; Ardino, V. Use of Somatic Experiencing Principles as a PTSD Prevention Tool for Children and Teens during the Acute Stress Phase Following an Overwhelming Event. In Post-Traumatic Syndromes in Childhood and Adolescence: A Handbook of Research and Practice; Ardino, V., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, A. Small Acts of Living: Everyday Resistance to Violence and Other Forms of Oppression. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 1997, 19, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, D. Safe and Together; DVRCV Advocate: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2013; pp. 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, M.; Arinero, M.; Soberon, C. Analysis of Effectiveness of Individual and Group Trauma-Focused Interventions for Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, R.; Eisma, M. Barriers and Facilitators of Disclosing Domestic Violence to the Healthcare Service: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 29, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniccia, D.; Leone, J. Theoretical Framework and Protocol for the Evaluation of Strong Through Every Mile (STEM), a Structured Running Program for Survivor’s of Intimate Partner Violence. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohn, E.; Tenkorang, E. Motivations and Barriers to Help-Seeking Among Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in Ghana. Violence Against Women 2022, 30, 524–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosi, M.; Rolling, E.; Gaffney, C.; Kitch, B. Beyond Resilience: Glimpses into Women’s Posttraumatic Growth after Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2020, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, C.; Tomasetto, C.; Guardabassi, V. Evaluating interventions with victims of intimate partner violence: A community psychology approach. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabold, N.; O’Malley, A.; Rizzo, L.; Russell, E. A gateway to healing: A community-based brief intervention for victims of violence. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, H. Online Group Psychotherapy: Challenges and Possibilities During COVID-19—A Practice Review. Group Dyn. 2020, 24, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsing, K.; Tonsing, J.; Orbuch, T. Domestic Violence, Social Support, Coping and Depressive Symptomatology amoung South Asian Women in Hong Kong. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 26, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenney, A.; Scott, K.; Wall, M. Mothers in Mind: Exploring the Efficacy of a Dyadic Group Parenting Intervention for Women Who Have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence and Their Young Children. Int. J. Child Maltreat. 2021, 5, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, L.; Kaspiew, R.; Taft, A. Domestic and Family Violence and Parenting: Mixed Methods Insights into Impact and Support Needs: State of Knowledge; ANROWS: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, L.; Strand, J.; Jutengren, G.; Tidefors, I. Perceptions and Experiences of an Attachment-Based Intervention for Parents Troubled by Intimate Partner Violence. Clin. Soc. Work 2016, 45, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.; Abrahams, H. A Review of the Provision of Intervention Programs for Female Victims and Survivors of Domestic Abuse in the United Kingdom. Fem. Inq. Soc. Work 2014, 29, 129–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, N.; Zemlak, J.; Celius, L.; Willie, T.; Kershaw, T.; Alexander, K. ‘If the Partner Finds Out, then there’s Trouble’: Provider Perspectives on Safety Planning and Partner Interference When Offering HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (Prep) to Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 2266–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, B.; Tharmarajah, S.; Njie-Carr, V.; Messing, J.; Loerzel, E.; Arscott, J.; Campbell, J. Safety Planning with Marginalized Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: Challenges of Conducting Safety Planning Intervention Research with Marginalized Women. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 23, 1728–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, C.; Healey, L.; Mandel, D. Case Reading as a Practice and Training Intervention in Domestic Violence and Child Protection. Aust. Soc. Work 2017, 71, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnardos Learn to Live Again Program Final Barnardos NSW, 2020.

- Wathen, N.; Mantler, T. Trauma-and Violence-Informed Care: Orienting Intimate Partner Violence Interventions to Equity. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2022, 9, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumarali, S.; Nnawulezi, N.; Eldridge, K.; Murphy, C.; Engleton, J. Survivors’ Perspectives on Relationship Violence Intervention Programs. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 38, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.; Eriksen, S.; Elklit, A. Effects of an Intervention Program for Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence on Psychological Symptoms and Perceived Social Support. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 24797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, L.; Goodman, L. What Is Empowerment Anyway? A Model for Domestic Violence Practice, Research, and Evaluation. Psychol. Violence 2015, 5, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valpied, J.; Cini, A.; O’Doherty, L.; Taket, A.; Hegarty, K. “Sometimes cathartic. Sometimes quite raw”: Benefit and harm in an intimate partner violence trial. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Milne-Ives, M.; Swancutt, D.; Burns, L.; Pinkney, J.; Tarrant, M.; Calitri, R.; Chatterjee, A.; Meinert, E. The Effectiveness and Usability of Online, Group-Based Interventions for People With Severe Obesity: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e26619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, A.; Drew, P.; Bower, P.; Brooks, H.; Gellatly, J.; Armitage, C.; Barkham, M.; McMillan, D.; Bee, P. Are there interactional differences between telephone and face-to-face psychological therapy? A systematic review of comparative studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, M.; Eng, L.; Gammon, D. Combining online and offline peer support groups in community mental health care settings: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Skinner, K.; Middleton, L.; Xiong, B.; Fang, M. Engaging Hard-to-Reach, Hidden, and Seldom-Heard Populations in Research. In Knowledge, Innovation, and Impact: A Guide for the Engaged Health Researcher: A Guide for the Engaged Health Researcher; Sixsmith, A., Sixsmith, J., Mihailidis, A., Fang, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

| Topic | Aim | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Introduction—what to expect | Gain an understanding of the program and how it supports participants | Group agreement Mindfulness activity (meditation) Islands of Safety activity; what does freedom from violence look like (use empty cup and supportive jar to visualise Islands of Safety) Introduce weekly journal |

| Week 2: Felt sense—turning into yourself | Explore personal strengths and help participants to begin to reconnect to their bodies | Strengths cards activity Islands of Safety: visited by women Mindfulness activity |

| Week 3: The Healing Tree—strength through growth | Builds on week 2 to help participants connect with their body to later help participants to learn to process trauma they have experienced | Strengths card activity Healing tree meditation Healing tree activity identifies individual’s supports, skills, beliefs/values, strengths, hopes, and dreams |

| Week 4: Letting go—the weight has lifted | Participants engage in activities to help them let go of negative energy | Strengths card activity Islands of Safety Release activity: release rock into a box/bucket Create individual or family identity shield |

| Week 5: Pathways of change—love myself | Participants identify their positive qualities and hopes and dreams for the future | Quality cards activity Islands of Safety Pathway of change activity: identifies supports, strategies and mechanisms for positive change and triggers for returning to perpetrator Love letter to yourself |

| Week 6: Patchwork life—goals and reality | Participants explore qualities that will support themselves and their children and identify goals | Breathing activity Island of Safety Cutting the cords and sharing wisdom Patchwork of Life Activity: create patchwork of identity diagram |

| Week 7: My kids & 1—giving and receiving love | Participants explore their strengths and their children’s strengths and the love that will help them to reconnect with their children | Strengths card activity: identify parenting strengths and children’s strengths Meditation activity Letter/card to children |

| Week 8: Reflection—pathways of change revisited | Participants reflect on their experiences of the program | Reflection and evaluation Review Pathway of change diagram |

| All weeks: Share morning tea with other participants, children and facilitators | Helps participants to develop sense of safety and trust between each other and with the facilitators | Journal time |

| Online Version of L2LA | Face-to-Face Version of L2LA | Total | Type of Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Former participants | 16 | 8 | 24 | Survey |

| Current participants | 2 | 6 | 8 | Interview |

| Current facilitators | 2 | 4 | 6 | Interview |

| Total | 20 | 18 | 38 |

| What motivated you to complete the program? Did you find this program beneficial? Do you feel the program’s delivery (including duration of sessions, the topic of sessions, and activities) was facilitated appropriately? Overall, how would you rate your experience taking part in the L2LA program? How engaged in the program did you feel? Did the program meet your expectations regarding what you hoped to get out of it? What topic did you find the least helpful? What topic did you find the most helpful? |

| Themes | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Get some light on everything”

|

|

| 2. | “Came together as a perfect puzzle”

|

|

| 3. | “Moving on and moving forward”

|

|

| 4. | Differences between the Online and Face-to-Face Facilitation

|

|

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| The focus is on how the program creates safe spaces, supporting women to support their children, being flexible and enhancing wellbeing. |

| Focuses on the practical processes the facilitators identified as important to the program’s success including the pre-group interview, post-referral process, the scheduling of the program, and safety planning. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cameron, J.; Rambaldini-Gooding, D.; Vezinias, K.; Smith, B.; Corsiglia, M.; Beale, S. Learn to Live Again: A Pilot Study to Support Women Experiencing Domestic Violence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050714

Cameron J, Rambaldini-Gooding D, Vezinias K, Smith B, Corsiglia M, Beale S. Learn to Live Again: A Pilot Study to Support Women Experiencing Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050714

Chicago/Turabian StyleCameron, Jacqui, Delia Rambaldini-Gooding, Kirsty Vezinias, Brooke Smith, Maria Corsiglia, and Sarah Beale. 2025. "Learn to Live Again: A Pilot Study to Support Women Experiencing Domestic Violence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050714

APA StyleCameron, J., Rambaldini-Gooding, D., Vezinias, K., Smith, B., Corsiglia, M., & Beale, S. (2025). Learn to Live Again: A Pilot Study to Support Women Experiencing Domestic Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050714