Differential Associations Between Individual Time Poverty and Smoking Behavior by Gender, Marital Status, and Childrearing Status Among Japanese Metropolitan Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept and Measurement of Time Poverty

2.2. Time Poverty, Health, and Gender: Evidence and Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

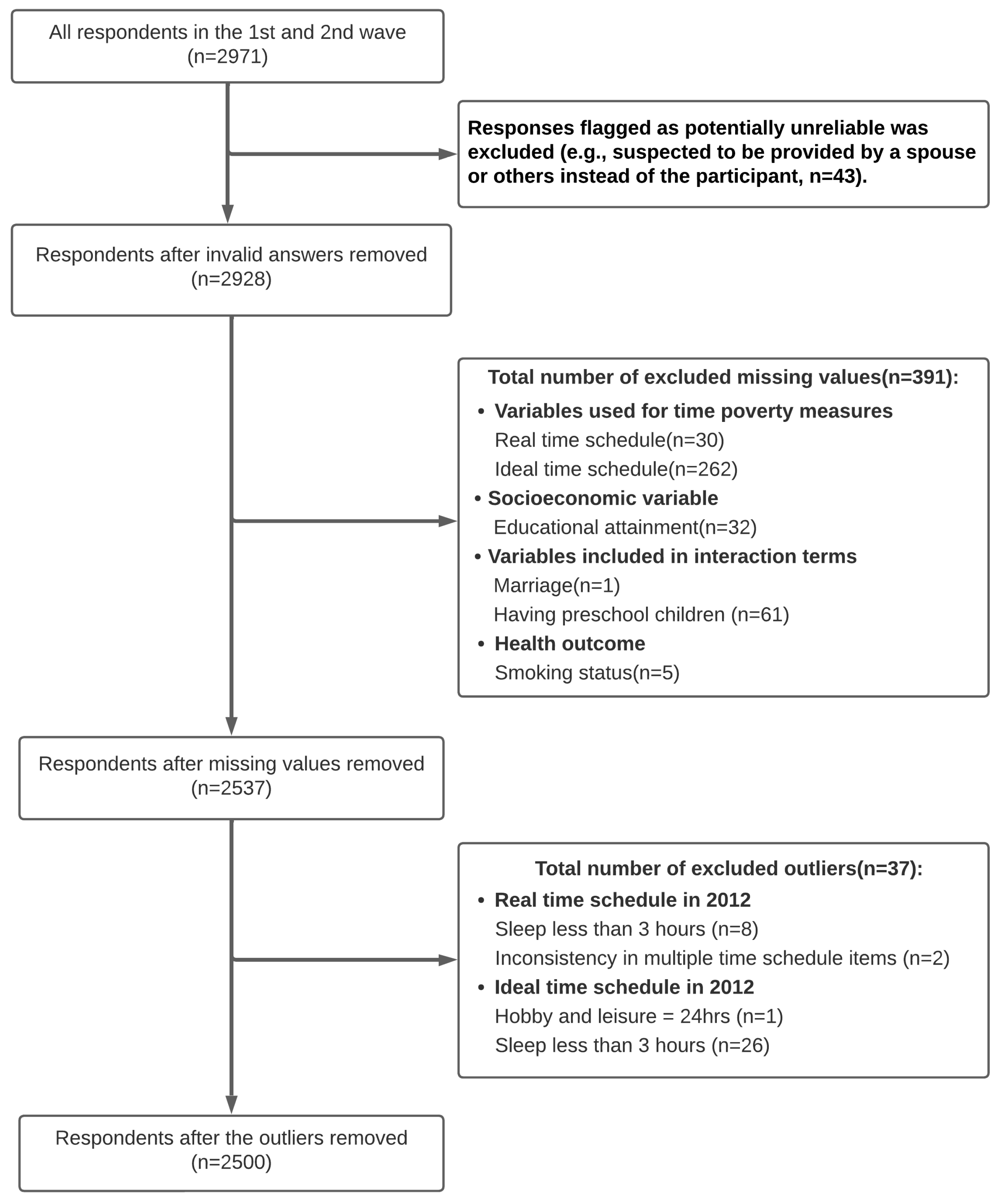

3.1. Data and Analytic Sample

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Explanatory Variable: Time Poverty

- Tr: actual leisure time;

- Ti: ideal leisure time;

- Td: difference between actual and ideal leisure time.

3.2.2. Outcome Variable

3.2.3. Covariates

3.2.4. Outliers and Missing Data

3.2.5. Analytical Method

4. Results

4.1. Basic Statistics

4.2. Smoking Rates by Time Poverty, Stratified by Gender, Marital Status, and Having Preschool-Age Children

4.3. Multivariable Regression Results

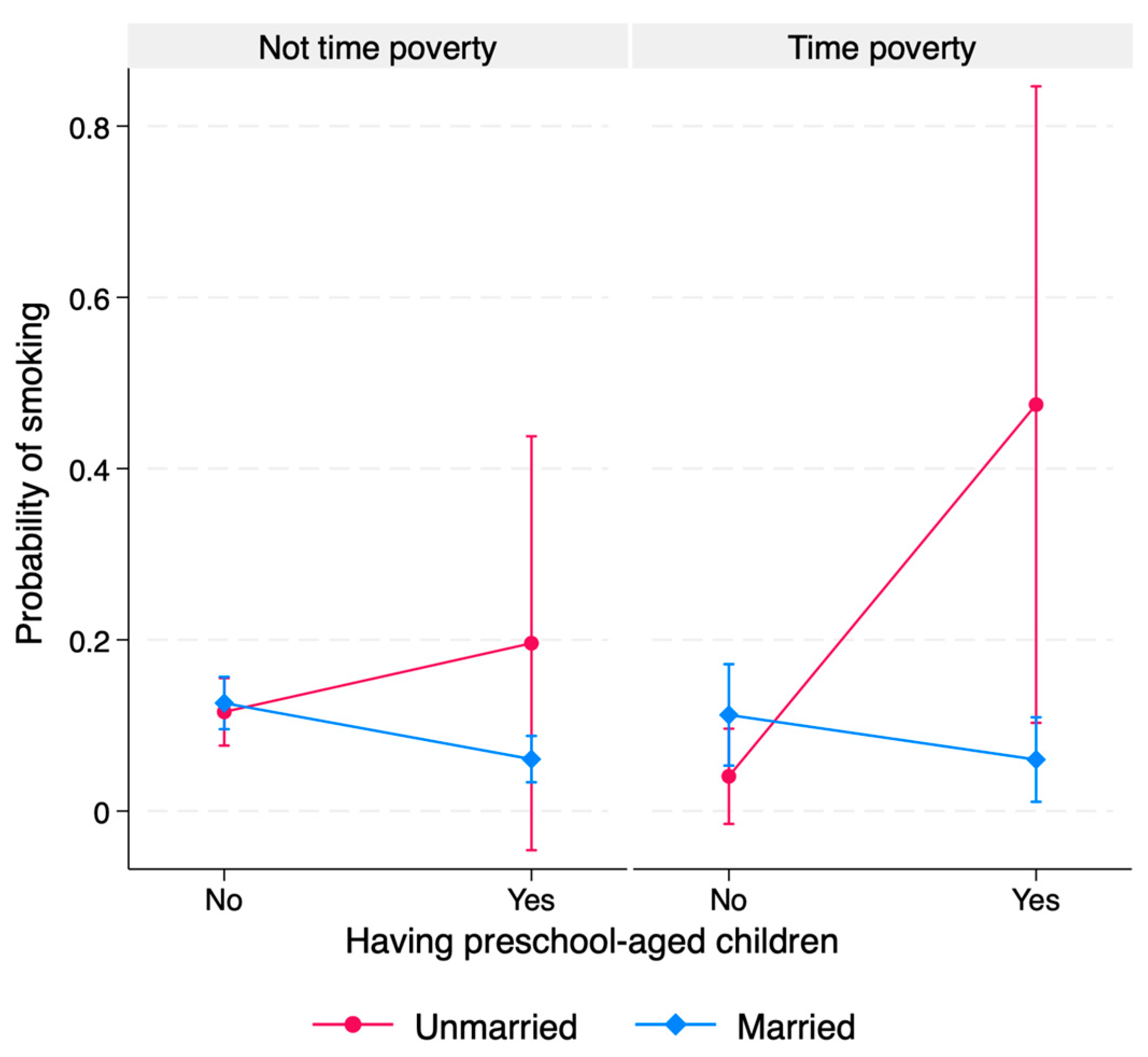

4.4. Heterogeneous Effects on Smoking Behavior

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lushniak, B.D.; Samet, J.M.; Pechacek, T.F.; Norman, L.A.; Taylor, P.A. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2014. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21569 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2012. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/dl/h24-houkoku.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000687163.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Reitsma, M.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Ababneh, E.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abedi, A.; Abhilash, E.S.; Abila, D.B.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Stirbu, I.; Roskam, A.-J.R.; Schaap, M.M.; Menvielle, G.; Leinsalu, M.; Kunst, A.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Altman, I. Handbook of Environmental Psychology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Bittman, M.; Goodin, R.E. An equivalence scale for time. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 52, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, M.; Rahkonen, O.; Karvonen, S.; Lahelma, E. Socioeconomic status and smoking. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 15, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazdins, L.; Welsh, J.; Korda, R.; Broom, D.; Paolucci, F. Not all hours are equal: Could time be a social determinant of health? Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakawa, K.; Wang, W.; Alam, M. Empirical analysis of time poverty and health-related activities in Japan. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 2020, 41, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Socioeconomic factors of multidimensional poverty for Japan’s young generation. Keizai Ronkyu 2016, 154, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheochari, S.; Arber, S. Class, gender and time poverty: A time-use analysis of British workers’ free time resources. Br. J. Sociol. 2012, 63, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès-Franch, I.; Arcas, M.M.; Ollé-Espluga, L.; Pérez, K. Time poverty, health and health-related behaviours in a southern European city: A gender issue. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2024, 78, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenkoski, C.M.; Hamrick, K.S.; Andrews, M. Time poverty thresholds and rates for the US population. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegary, H.; Landy, F.J. The interactions among time urgency, uncertainty, and time pressure. In Time Pressure and Stress in Human Judgment and Decision Making; Svenson, O., Maule, A.J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe, W.; Lyons, K. A predictive model of chronic time pressure in the Australian population: Implications for leisure research. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, S. Subjective time pressure: General or domain specific? Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 47, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickery, C. The time-poor: A new look at poverty. J. Hum. Resour. 1977, 12, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittman, M. Social participation and family welfare: The money and time costs of leisure in Australia. Soc. Policy Adm. 2002, 36, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, T. Time and Income Poverty. 2008. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1401768 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Bó, B. Time availability as a mediator between socioeconomic status and health. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, T. Time, income and substantive freedom: A capability approach. Time Soc. 2010, 19, 318–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.R.; Masuda, Y.J.; Tallis, H. A measure whose time has come: Formalizing time poverty. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalenkoski, C.M.; Hamrick, K.S. How does time poverty affect behavior? A look at eating and physical activity. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2013, 35, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair-Loy, M.; Hochschild, A.; Pugh, A.J.; Williams, J.C.; Hartmann, H. Stability and transformation in gender, work, and family: Insights from the second shift for the next quarter century. Community Work Fam. 2015, 18, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Meulen Rodgers, Y. Time poverty: Conceptualization, gender differences, and policy implications. Soc. Philos. Policy 2023, 40, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, M.J.; Blanchi, S.M. Gender differences in the quantity and quality of free time: The U.S. experience. Soc. Forces 2003, 81, 999–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessing, M. More than Clockwork: Women’s Time Management in Their Combined Workloads. Sociol. Perspect. 1994, 37, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.-J.; Acevedo-Garcia, D. The effect of single motherhood on smoking by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperlich, S.; Nyambura Maina, M.; Noeres, D. The effect of psychosocial stress on single mothers’ smoking. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, M.; Kondo, N.; Hashimoto, H.; J-Shine Data Management Committee. Japanese Study on Stratification, Health, Income, and Neighborhood: Study protocol and profiles of participants. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, J.L.; Graham, J.W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, P. Methods for estimating adjusted risk ratios. Stata J. 2009, 9, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, K.; Kurumatani, N.; Saeki, K. The association between education and smoking prevalence, independent of occupation: A nationally representative survey in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinney, J.; Millward, H. Time and money: A new look at poverty and the barriers to physical activity in Canada. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 99, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, M.J. The association between having children, family size and smoking cessation in adults. Addiction 1996, 91, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppanner, L.; Perales, F.; Baxter, J. Harried and unhealthy? Parenthood, time pressure, and mental health. J. Marriage Fam. 2019, 81, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsteen, K.; Ross, C.E. The perceived burden of children. J. Fam. Issues 1989, 10, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, T.; Lange, S.; Tröster, H. Cumulative stress of single mothers: An exploration of potential risk factors. TFJ 2023, 31, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Parents Under Pressure: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Mental Health & Well-Being of Parents. 2024. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39250580 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK595227 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Allen, M.; Allen, J.; Hogarth, S.; Marmot, M. Working for Health Equity: The Role of Health Professionals. 2013. Available online: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/working-for-health-equity-the-role-of-health-professionals (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- te Braak, P.; van Tienoven, T.P.; Minnen, J.; Glorieux, I. Data quality and recall bias in time-diary research: The effects of prolonged recall periods in self-administered online time-use surveys. Sociol. Methodol. 2023, 53, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihama, Y.; Nakayama, S.F.; Tabuchi, T.; Isobe, T.; Jung, C.-R.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Michikawa, T.; Sekiyama, M.; Taniguchi, Y.; et al. Determination of urinary cotinine cut-off concentrations for pregnant women in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Your Daily Time Use on Weekdays | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commuting to work or school | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Work | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Housework and shopping for daily necessities | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Childcare | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Caregiving (parents, spouse, family) | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Exercise, sports, walking | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Learning and lessons | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Community service, volunteer, political activities | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Hobbies, entertainment, socializing | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Rest and relaxation (excluding sleep) | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Sleep duration | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Meals, personal care, etc. | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Total time per day | X | X | hrs. | X | 0 | min. |

| Total (N = 2500) | Men (N = 1125) | Women (N = 1375) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age (mean ± SD *) | 37.6 | 7.0 | 37.9 | 7.0 | 37.3 | 7.0 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| High | 1892 | 75.7 | 837 | 74.4 | 1055 | 76.7 |

| Unmarried | 687 | 27.5 | 332 | 29.5 | 355 | 25.8 |

| Having preschool-age children | 685 | 27.4 | 318 | 28.3 | 367 | 26.7 |

| Current smoker | 509 | 20.4 | 367 | 32.6 | 142 | 10.3 |

| Time poverty | 412 | 16.5 | 179 | 15.9 | 233 | 16.9 |

| Men | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marriage | Having Preschool-Age Children | Total | Marriage | Having Preschool-Age Children | Total | |||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| Without time poverty | 32.87% | 31.52% | 31.45% | 33.09% | 31.92% | 11.73% | 10.18% | 11.73% | 7.12% | 10.60% |

| With time poverty | 30.43% | 38.35% | 36.03% | 37.21% | 36.31% | 8.33% | 9.19% | 9.52% | 8.14% | 9.01% |

| Total | 32.53% | 32.66% | 32.22% | 33.65% | 32.62% | 11.27% | 10.00% | 11.41% | 7.36% | 10.33% |

| Model 1 | Model 2 (Including Interaction Terms) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-Value | 95% CI | Coef. | p-Value | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| (1) | ||||||||

| Age | −0.00 | 0.80 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.75 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Junior high school/high school (ref.) | ||||||||

| College/graduate school | −0.51 | 0.00 *** | −0.68 | −0.34 | −0.51 | 0.00 *** | −0.68 | −0.35 |

| Married | ||||||||

| Yes (ref.) | ||||||||

| No | 0.04 | 0.70 | −0.18 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.52 | −0.16 | 0.33 |

| Has preschool-age children | ||||||||

| No (ref.) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.05 | 0.62 | −0.16 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.48 | −0.15 | 0.33 |

| Time poverty | ||||||||

| No (ref.) | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.08 | 0.48 | −0.14 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.17 | −0.09 | 0.50 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| 0.26 | 0.65 | −0.86 | 1.37 | ||||

| −0.28 | 0.33 | −0.83 | 0.27 | ||||

| −0.23 | 0.38 | −0.74 | 0.28 | ||||

| NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| (2) | ||||||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Junior high school/high school (ref.) | ||||||||

| College/graduate school | −1.03 | 0.00 *** | −1.34 | −0.72 | −1.01 | 0.00 *** | −1.32 | −0.70 |

| Married | ||||||||

| Yes (ref.) | ||||||||

| No | −0.03 | 0.89 | −0.46 | 0.40 | −0.09 | 0.71 | −0.53 | 0.36 |

| Has preschool-age children | ||||||||

| No (ref.) | ||||||||

| Yes | −0.53 | 0.03 ** | −0.99 | −0.07 | −0.73 | 0.01 ** | −1.26 | −0.21 |

| Time poverty | ||||||||

| No (ref.) | ||||||||

| Yes | −0.18 | 0.42 | −0.61 | 0.25 | −0.21 | 0.68 | −0.67 | 0.44 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| 1.26 | 0.07 * | −0.12 | 2.64 | ||||

| −0.93 | 0.23 | −2.45 | 0.59 | ||||

| 0.11 | 0.85 | −0.98 | 1.20 | ||||

| 1.83 | 0.12 | −0.47 | 4.12 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaki, M.; Hashimoto, H. Differential Associations Between Individual Time Poverty and Smoking Behavior by Gender, Marital Status, and Childrearing Status Among Japanese Metropolitan Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050655

Kaki M, Hashimoto H. Differential Associations Between Individual Time Poverty and Smoking Behavior by Gender, Marital Status, and Childrearing Status Among Japanese Metropolitan Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050655

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaki, Mimori, and Hideki Hashimoto. 2025. "Differential Associations Between Individual Time Poverty and Smoking Behavior by Gender, Marital Status, and Childrearing Status Among Japanese Metropolitan Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050655

APA StyleKaki, M., & Hashimoto, H. (2025). Differential Associations Between Individual Time Poverty and Smoking Behavior by Gender, Marital Status, and Childrearing Status Among Japanese Metropolitan Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050655