A Stress Management and Health Coaching Intervention to Empower Office Employees to Better Control Daily Stressors and Adopt Healthy Routines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Process

2.2. Intervention Group

- -

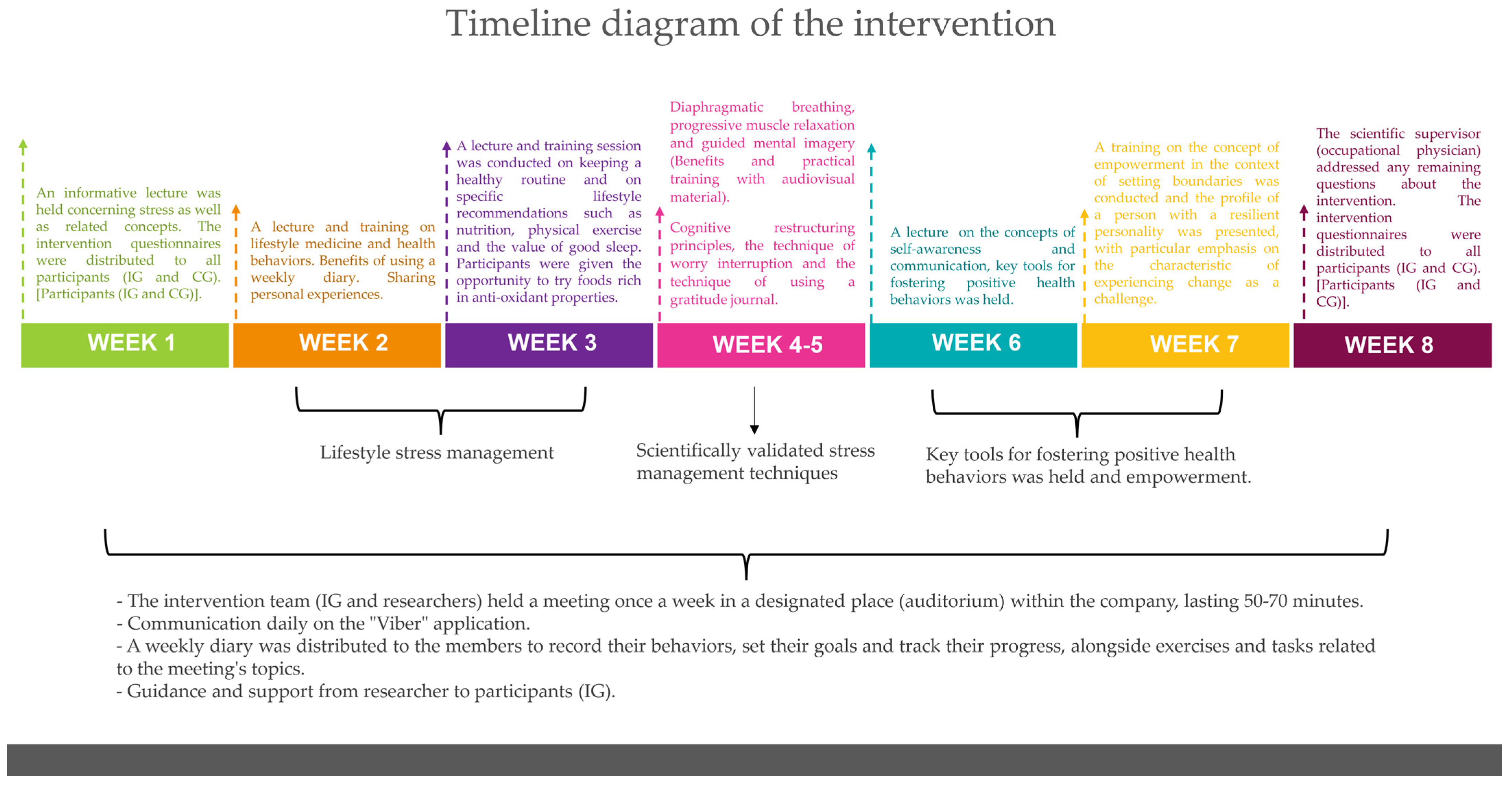

- In week 1, an informative lecture was held concerning stress as well as related concepts (stress system; chronic stress effects: symptoms and diseases; stress and anxiety). At the end of the session, the intervention questionnaires were distributed to all participants (IG and CG). The control group did not participate in any other meeting and remained on a waiting list.

- -

- In the 2nd week, a lecture and training on lifestyle medicine, health behaviors and how they are linked to stress and chronic diseases as well as the process of changing harmful health behaviors took place. The purpose of the second meeting was to encourage active participation from the members of the IG with an emphasis on sharing personal experiences. Additionally, the importance of maintaining a journal as a measure of self-monitoring was analyzed. A weekly diary was distributed to the members to record their behaviors, set their goals and track their progress, alongside exercises and tasks related to the meeting’s topics.

- -

- In week 3, a lecture and training session on keeping a healthy routine and on specific lifestyle recommendations such as nutrition, physical exercise and the value of good sleep was conducted. Participants were given the opportunity to try foods rich in antioxidant properties. A new weekly diary was distributed to the members to record their behaviors, their goals and their achievements and additional exercises related to the meeting’s theme were assigned.

- -

- In the 4th and 5th weeks, training focused on scientifically validated stress management techniques after highlighting their benefits by communicating relevant studies. The techniques included diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation and guided mental imagery. The relaxation techniques focus on the conscious and controlled release of muscular tension. The combination of two or more relaxation techniques has proven to be effective in reducing stress [9,10,12]. Guided imagery is a stress management technique that shifts the participant’s attention to an envisioned mental image of flavors, sounds, sights, scents and emotions. The positive outcomes of this exercise are numerous, including stress reduction and aiding those who experience sleep disorders. In addition, during these two weeks, the participants were trained in additional skills using cognitive restructuring principles, the technique of worry interruption and the technique of using a gratitude journal. Cognitive restructuring is a process used in the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach, aimed at modifying dysfunctional thoughts, opinions, ideas and perceptions—referred to as cognitions—as well as behaviors that hinder an individual’s life [21]. The strategy of stopping thought involves deliberately following worry with a simple aversive consequence. The gratitude journal introduces the brain to the habit of scanning the surrounding environment for positive things [22]. New journals were distributed each week to allow participants to track the frequency of practicing with these techniques as well as to record lifestyle changes (e.g., exercise, diet and sleep). Exercises related to the themes of these three sessions were also assigned.

- -

- In week 6, a session centered on the concepts of self-awareness and communication as key tools for fostering positive health behaviors was held. It was emphasized that through self-awareness and effective communication—both with oneself and others—individual empowerment is enhanced, leading to improved health and lower stress levels. Finally, exercises and assignments related to the lecture topics were given to complete before the next meeting.

- -

- In week 7, to complete the intervention sessions, training on the concept of empowerment in the context of setting boundaries was conducted and the profile of a person with a resilient personality was presented, with particular emphasis on the characteristic of experiencing change as a challenge. Finally, exercises and assignments related to the lecture topics were given to complete before the next meeting.

- -

- In the 8th and last week, the scientific supervisor (occupational physician) addressed any remaining questions about the intervention and the intervention questionnaires were redistributed for completion and were returned within 10 days.

2.3. Control Group (Waiting List Group)

2.4. Tools and Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action. For Employers, Workers, Policy-Makers and Practitioners; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ganster, D.C.; Rosen, C.C. Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1085–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.; Cox, T.; Dewe, P.; Cosmar, M.; Gründler, R.; Flemming, D.; Cosemans, B.; Van den Broek, K. Calculating the Costs of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Christianson, M.K.; Price, R.H. Happiness, health, or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.A.; Iavicoli, I.; Fontana, L.; Leka, S.; Dollard, M.F.; Salmen-Navarro, A.; Salles, F.J.; Olympio, K.P.K.; Lucchini, R.; Fingerhut, M.; et al. Occupational safety and health staging framework for decent work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forastieri, V. Prevention of psychosocial risks and work-related stress. Int. J. Labour Res. 2016, 8, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.; Rose, J.; Mason, O.; Tyler, P.; Cushway, D. Cognitive therapy and behavioural coping in the management of work-related stress: An intervention study. Work Stress 2005, 19, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioula, E.K.; Tigani, X.; Artemiadis, A.K.; Vlachakis, D.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C.; Alexopoulos, E.C. An 8-week Stress Management Program in Information Technology Professionals and the Role of a New Cognitive Behavioral Method: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Mol. Biochem. 2020, 9, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, E.C.; Zisi, M.; Manola, G.; Darvin, C. Short-term effects of a randomized controlled worksite relaxation intervention in Greece. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2014, 21, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-Fleitas, L.; Franco-Pérez, Á.; Caballero, P.; Sanz-Lorente, M.; Wanden-Berghe, C.; Sanz-Valero, J. Influence of Nutrition, Food and Diet-Related Interventions in the Workplace: A Meta-Analysis with Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouli, E.; Pavlopoulos, V.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Chrousos, G.; Darviri, C. Short-term impact of a stress management and health promotion program on perceived stress, parental stress, health locus of control and cortisol levels in parents of children and adolescents with diabetes type 1: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Explore 2014, 10, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, S.-J.; Carroll, A.; McCuaig-Holcroft, L. A Complementary Intervention to Promote Wellbeing and Stress Management for Early Career Teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koseoglu Ornek, O.; Esin, M.N. Effects of a work-related stress model based mental health promotion program on job stress, stress reactions and coping profiles of women workers: A control groups study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1658. [Google Scholar]

- Dejonghe, L.A.; Biallas, B.; McKee, L.; Rudolf, K.; Froböse, I.; Schaller, A. Expectations Regarding Workplace Health Coaching: A Qualitative Study with Stakeholders. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, S.; Curtain, S. Health coaching as a lifestyle medicine process in primary care. R. Aust. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2019, 48, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolever, R.Q.; Caldwell, K.L.; McKernan, L.C.; Hillinger, M.G. Integrative Medicine Strategies for Changing Health Behaviors: Support for Primary Care. Support Prim. Care 2017, 44, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoert, J.; Cabanas, M.; Hofmann, R. The Role of Leadership Support for Health Promotion in Employee Wellness Program Participation, Perceived Job Stress, and Health Behaviors. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 32, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Di Tecco, C.; Nielsen, K.; Ghelli, M.; Ronchetti, M.; Marzocchi, I.; Persechino, B.; Iavicoli, S. Improving Working Conditions and Job Satisfaction in Healthcare: A Study Concept Design on a Participatory Organizational Level Intervention in Psychosocial Risks Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.L.; Vryonis, M.M.; Protogerou, A.D.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Achimastos, A.; Papadogiannis, D.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C. Stress management and dietary counseling in hypertensive patients: A pilot study of additional effect. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2014, 15, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S. Cognitive Therapy for Challenging Problems; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.H. Does expressive writing reduce health care utilization? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darviri, C.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Artemiadis, A.K.; Tigani, X.; Kraniotou, C.; Darvyri, P.; Chrousos, G.P. The Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ): A novel tool for assessing self-empowerment through a constellation of daily activities. BMC Public Health 2014, 24, 995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andreou, E.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Lionis, C.; Varvogli, L.; Gnardellis, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Darviri, C. Perceived stress scale: Reliability and validity study in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3287–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Galanou, C.; Galanakis, M.; Alexopoulos, E.; Darviri, C. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Greek Validation on Student Sample. Psychology 2014, 5, 819–827. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Karakasidou, E.; Pezirkianidis, C.; Stalikas, A.; Galanakis, M. Standardization of the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) in a Greek Sample. Psychology 2016, 7, 1753–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynou, E.; Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Greek Adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. 1994. Available online: https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/%7Ehealth/greek.htm (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Pilafas, G.; Lyrakos, G.; Louka, P. Testing the Validity and Reliability of the Greek Version of General Self-Efficacy (GSE) Scale. Galore Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2024, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds CF 3rd Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kotronoulas, G.C.; Papadopoulou, C.N.; Papapetrou, A.; Patiraki, E. Psychometric evaluation and feasibility of the Greek Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (GR-PSQI) in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1831–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, L.; Martin, A.; Neil, A.L.; Memish, K.; Otahal, P.; Kilpatrick, M.; Sanderson, K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Workplace Mindfulness Training Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Chad-Friedman, E.; Pearsall, M.; Miller, K.M.; Wheeler, A.E.; Denninger, J.W.; Mehta, D.H.; Dossett, M.L. Total Lifestyle Coaching: A Pilot Study Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Mind–Body and Nutrition Telephone Coaching Program for Obese Adults at a Community Health Center. Global Adv. Health Med. 2018, 7, 2164956118784902. [Google Scholar]

- Lacagnina, S.; Moore, M.; Mitchell, S. The Lifestyle Medicine Team: Health Care That Delivers Value. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2018, 12, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.; Saba, G.; Wolf, J.; Gardner, H.; Thom, D.H. What do health coaches do? Direct observation of health coach activities during medical and patient-health coach visits at 3 federally qualified health centers. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 18) | All (N = 38) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender—n (%) | ||||

| Male | 10 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | 21 (55.3) | 0.53 |

| Female | 10 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | 17 (44.7) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI)—n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 1 (5.0) | - | 1 (2.6) | 0.24 |

| Normal weight | 8 (40.0) | 5 (27.8) | 13 (34.2) | |

| Overweight | 11 (55.0) | 10 (55.6) | 21 (55.3) | |

| Obese | - | 3 (16.7) | 3 (7.9) | |

| Marital Status—n (%) | ||||

| Single | 6 (30.0) | 1 (5.6) | 7 (18.4) | 0.13 |

| Divorced | 3 (15.0) | 2 (11.1) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Married | 11 (55.0) | 15 (83.3) | 26 (68.4) | |

| Education—n (%) | ||||

| High School and/or Vocational Training | 6 (30.0) | 4 (22.3) | 10 (26.3) | 0.64 |

| University/Technological Institute | 9 (45.0) | 8 (44.4) | 17 (44.7) | |

| Postgraduate | 5 (25.0) | 6 (33.3) | 11 (28.9) | |

| Coverage of needs—n (%) | ||||

| Barely or hardly | 2 (10.0) | - | 2 (5.2) | 0.32 |

| Moderately | 14 (70.0) | 11 (61.1) | 25 (65.8) | |

| Fully | 3 (15.0) | 7 (38.9) | 10 (26.3) | |

| Unknown | 1 (5.0) | - | 1 (2.6) | |

| Previous Experience—n (%) | ||||

| ≤20 έτη | 10 (50.0) | 10 (55.6) | 20 (52.6) | 0.76 |

| >20 έτη | 10 (50.0) | 8 (44.4) | 18 (47.4) | |

| Smoker—n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (15.0) | 2 (11.1) | 5 (13.2) | >0.99 |

| Former | 4 (20.0) | 3 (16.7) | 7 (18.4) | |

| No | 13 (65.0) | 13 (72.2) | 26 (68.4) | |

| Age (in years) | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 42.9 (39.6–46.2) | 50.8 (48.1–53.6) | 46.7 (44.2–49.1) | 0.0016 § |

| Median (Min–Max) | 46.0 (28–52) | 51.0 (43–60) | 46.5 (28–60) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 24.8 (23.5–26.2) | 26.4 (24.8–28) | 25.6 (24.6–26.6) | 0.16 § |

| Median (Min–Max) | 25.1 (17.7–29.1) | 25.9 (22.5–33.5) | 25.5 (17.7–33.5) |

| Before the Intervention | After the Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 18) | p-Value # | IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 18) | p-Value # |

| HLPCQ | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 63.1 (57.1–69.1) | 60.6 (56.6–64.5) | 0.12 | 66.3 (60.3–72.3) | 60.6 (56.6–64.5) | 0.021 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 66.5 (33–81) | 58.5 (50–78) | 69.0 (36–86) | 58.5 (50–78) | ||

| PSS-14 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 25.4 (22.4–28.4) | 26.3 (24.4–28.3) | 0.30 | 21.4 (17.5–25.3) | 26.3 (24.4–28.3) | 0.001 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 25.0 (12–39) | 27.5 (16–32) | 20.0 (10–50) | 27.5 (16–32) | ||

| SES | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 22.3 (20.3–24.3) | 20.2 (18.7–21.7) | 0.054 | 22.5 (20.5–24.4) | 20.2 (18.7–21.7) | 0.069 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 22.5 (12–30) | 19.5 (16–25) | 23 (14–30) | 19.5 (16–25) | ||

| SHS | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 4.4 (3.9–4.9) | 0.071 | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 4.4 (3.9–4.9) | 0.025 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 5.3 (1.7–7.0) | 4.3 (2.5–6.3) | 5.3 (1.5–6.5) | 4.3 (2.5–6.3) | ||

| GSES | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 28.9 (26.5–31.2) | 27.4 (25.5–29.3) | 0.28 | 29.9 (27.9–31.8) | 27.4 (25.5–29.3) | 0.031 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 29.0 (16–39) | 27.5 (19–34) | 30.0 (18–37) | 27.5 (19–34) | ||

| PSQI | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 4.4 (3.3–5.4) | 4.2 (3.2–5.1) | 0.76 | 4.3 (3.1–5.5) | 4.2 (3.2–5.1) | 0.72 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 3.5 (2–11) | 4.0 (0–9) | 4 (1–13) | 4 (0–9) | ||

| Before the Intervention | After the Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 18) | p-Value # | IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 18) | p-Value # |

| Dietary Healthy Choices | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 15.7 (13.8–17.6) | 15.2 (14.1–16.4) | 0.65 | 15 (13.1–16.8) | 15.2 (14.1–16.4) | 0.69 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 15.5 (9–24) | 15.0 (11–19) | 15 (9–24) | 15 (11–19) | ||

| Dietary Harm Avoidance | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 8.8 (7.8–9.7) | 9.2 (8.0–10.3) | 0.40 | 9.1 (8.0–10.1) | 9.2 (8.0–10.3) | 0.78 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 9.0 (4–12) | 9.5 (4–12) | 10.0 (4–13) | 9.5 (4–12) | ||

| Daily Routine | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 21.6 (18.9–24.2) | 21.8 (19.6–24.1) | 0.86 | 23.7 (21.2–26.1) | 21.8 (19.6–24.1) | 0.15 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 22.5 (8–31) | 23.0 (12–28) | 24 (11–30) | 23 (12–28) | ||

| Organized Physical Exercise | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 4.7 (3.7–5.7) | 4.9 (4.0–5.9) | 0.76 | 4.7 (3.7–5.7) | 4.9 (4–5.9) | 0.65 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 5.0 (2–8) | 4.5 (2–8) | 4 (2–8) | 4.5 (2–8) | ||

| Social and Mental Balance | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 12.4 (11.0–13.8) | 10.3 (9.2–11.3) | 0.024 | 14 (12.6–15.3) | 10.3 (9.2–11.3) | <0.001 |

| Median (Min–Max) | 12.5 (7–17) | 10.0 (7–15) | 15 (7–17) | 10 (7–15) | ||

| Scale and Subscales | Mean Difference (95% C.I.) | p-Value # |

|---|---|---|

| HLPCQ | −3.20 (−6.37, −0.02) | 0.048 |

| Dietary Healthy Choices | 0.75 (−0.39, 1.89) | 0.186 |

| Dietary Harm Avoidance | −0.30 (−0.93, 0.33) | 0.329 |

| Daily Routine | −2.10 (−3.63, −0.57) | 0.001 |

| Organized Physical Exercise | 0 (−0.92, 0.92) | >0.99 |

| Social and Mental Balance | −1.55 (−2.48, 0.62) | 0.003 |

| PSS-14 | 4.00 (0.12, 7.88) | 0.043 |

| SES | −0.15 (−1.11, 0.81) | 0.748 |

| SHS | −0.15 (−0.58, 0.28) | 0.470 |

| GSES | −1.00 (−2.31, 0.31) | 0.126 |

| PSQI | 0.05 (−1.22, 1.32) | 0.935 |

| b for Time | p-Value | b for Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLPCQ total scale | −1.684 | 0.051 | 4.144 | 0.231 |

| HLPCQ subscale | ||||

| Dietary Healthy Choices | 0.394 | 0.183 | 0.102 | 0.921 |

| Dietary Harm Avoidance | −0.157 | 0.323 | −0.266 | 0.704 |

| Daily Routine | −1.105 | 0.011 | 0.766 | 0.631 |

| Organized Physical Exercise | <0.001 | >0.999 | −0.244 | 0.695 |

| Social and Mental Balance | −0.815 | 0.004 | 2.897 | 0.001 |

| PSS-14 | 2.105 | 0.045 | −2.933 | 0.093 |

| SES | −0.078 | 0.743 | 2.152 | 0.076 |

| SHS | −0.079 | 0.463 | 0.573 | 0.103 |

| GSES | −0.526 | 0.124 | 1.961 | 0.157 |

| PSQI | 0.026 | 0.933 | 0.158 | 0.807 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziaka, D.; Tigani, X.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Alexopoulos, E.C. A Stress Management and Health Coaching Intervention to Empower Office Employees to Better Control Daily Stressors and Adopt Healthy Routines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040548

Ziaka D, Tigani X, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Alexopoulos EC. A Stress Management and Health Coaching Intervention to Empower Office Employees to Better Control Daily Stressors and Adopt Healthy Routines. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040548

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiaka, Despoina, Xanthi Tigani, Christina Kanaka-Gantenbein, and Evangelos C. Alexopoulos. 2025. "A Stress Management and Health Coaching Intervention to Empower Office Employees to Better Control Daily Stressors and Adopt Healthy Routines" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040548

APA StyleZiaka, D., Tigani, X., Kanaka-Gantenbein, C., & Alexopoulos, E. C. (2025). A Stress Management and Health Coaching Intervention to Empower Office Employees to Better Control Daily Stressors and Adopt Healthy Routines. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 548. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040548