The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Chinese Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Chain Mediation of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Distributed Leadership and Conservation of Resources Theory

2.2. The Relationship Between Distributed Leadership and Teacher Job Satisfaction

2.3. The Mediating Role of Teacher Collaboration

2.4. The Mediating Role of Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.5. The Chained Mediating Role of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Research Variables

3.2.1. Independent Variable

3.2.2. Dependent Variable

3.2.3. Mediating Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

4. Research Results

4.1. Common Method Bias and Discriminant Validity Testing

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

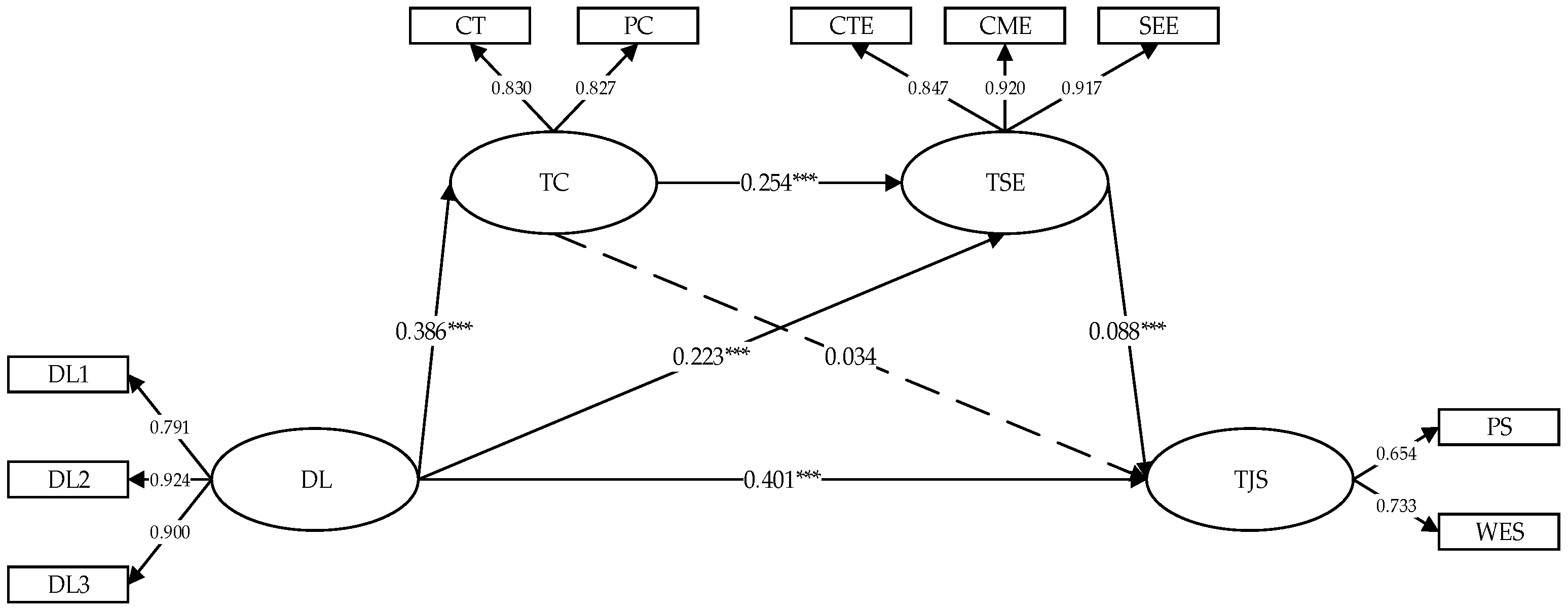

4.3. Chain Mediation Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Association Between Distributed Leadership and Teacher Job Satisfaction

5.2. Independent Mediating Role of Teacher Self-Efficacy and Teacher Collaboration

5.3. Chain Mediation Role of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CME | Classroom management efficacy |

| COR | Conservation of resources |

| CT | Coordination for teaching |

| CTE | Classroom teaching efficacy |

| DL | Distributed leadership |

| EA | Educational attainment |

| PC | Professional collaboration |

| PPS | Probability proportional to size |

| PS | Professional satisfaction |

| SEE | Student engagement efficacy |

| SEM | Structural equation models |

| TALIS | Teaching and Learning International Survey |

| TC | Teacher collaboration |

| TE | Teaching experience |

| TJS | Teacher job satisfaction |

| TSE | Teacher self-efficacy |

| WES | Work environment satisfaction |

Appendix A

| Scale | Subscale | Item | Response Option |

| DL | This school provides staff with opportunities to actively participate in school decisions. This school has a culture of shared responsibility for school issues. There is a collaborative school culture that is characterized by mutual support. |

| |

| TJS | PS | The advantages of being a teacher clearly outweigh the disadvantages. If I could decide again, I would still choose to work as a teacher. I regret that I decided to become a teacher. I wonder whether it would have been better to choose another profession. |

|

| WES | I would like to change to another school if that were possible. I enjoy working at this school. I would recommend this school as a good place to work. All in all, I am satisfied with my job. | ||

| TC | PC | Teach jointly as a team in the same class. Observe other teachers’ classes and provide feedback. Engage in joint activities across different classes and age groups (e.g., projects). Take part in collaborative professional learning. |

|

| CT | Teach jointly as a team in the same class. Exchange teaching materials with colleagues. Engage in discussions about the learning development of specific students. Work with other teachers in this school to ensure common standards in evaluations for assessing student progress. | ||

| TSE | CTE | Craft good questions for students. Use a variety of assessment strategies. Provide an alternative explanation, for example, when students are confused. Vary instructional strategies in my classroom. |

|

| CME | Control disruptive behavior in the classroom. Make my expectations about student behavior clear. Get students to follow classroom rules. Calm a student who is disruptive or noisy. | ||

| SEE | Get students to believe they can do well in school work. Help students value learning. Motivate students who show low interest in school work. Help students think critically. |

References

- Brandmiller, C.; Schnitzler, K.; Dumont, H. Teacher perceptions of student motivation and engagement: Longitudinal associations with student outcomes. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 1397–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M.; Klusmann, U.; Baumert, J.; Richter, D.; Voss, T.; Hachfeld, A.; Graesser, A.C. Professional Competence of Teachers: Effects on Instructional Quality and Student Development. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.; Matas, C.P. Teacher attrition and retention research in Australia: Towards a new theoretical framework. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Improving Education in Africa: Insights from Research Across 33 Countries; UNICEF Innocenti: Florence, Italy, 2024; p. 3. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/improving-education-africa (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Di Pietro, G. Indicators for Monitoring Teacher Shortage in the European Union: Possibilities and Constraints; Joint Research Centre: Seville, Spain, 2023; p. 5. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC134239 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Sorensen, L.C.; Ladd, H.F. The Hidden Costs of Teacher Turnover. AERA Open 2020, 6, 310556844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do About It; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–3. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-turnover-report (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Asif, M.; Li, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A.; Hu, W. Impact of perceived supervisor support and leader-member exchange on employees’ intention to leave in public sector museums: A parallel mediation approach. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1131896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Jinnai, Y. Effects of Monetary Incentives on Teacher Turnover: A Longitudinal Analysis. Public Pers. Manag. 2021, 50, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; p. 15. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/talis-2018-results-volume-ii_19cf08df-en.html (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Gundlach, H.A.D.; Slemp, G.R.; Hattie, J. A meta-analysis of the antecedents of teacher turnover and retention. Educ. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, K.C.; McCarthy, C.J.; Lambert, R.G.; Caldwell, A.B. Understanding teacher professional intentions: The role of teacher psychological resources, appraisals, and job satisfaction. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchsman, D.; Sass, T.R.; Zamarro, G. Testing, Teacher Turnover, and the Distribution of Teachers across Grades and Schools. Educ. Financ. Policy 2023, 18, 654–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.Y.; Liao, P.W.; Lee, Y.H. Teacher Motivation and Relationship Within School Contexts as Drivers of Urban Teacher Efficacy in Taipei City. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2022, 31, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjork, C. High-Stakes Schooling; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukgoze, H.; Caliskan, O.; Gümüş, S. Linking distributed leadership with collective teacher innovativeness: The mediating roles of job satisfaction and professional collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024, 52, 1388–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Tang, R. School support for teacher innovation: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Think. Skills Creat. 2022, 45, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, E.; Öztekin, Ö.; Karadağ, E. The effect of leadership on job satisfaction. In Leadership and Organizational Outcomes: Meta-Analysis of Empirical Studies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; DeFlaminis, J. Distributed leadership in practice: Evidence, misconceptions and possibilities. Manag. Educ. 2016, 30, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, D.G. Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction in US schools. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J.B. Towards a theory of leadership practice: A distributed perspective. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaya, M.; Berkovich, I. Participative decision making in schools in individualist and collectivist cultures: The micro-politics behind distributed leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bellibaş, M.Ş.; Gümüş, S. The Effect of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Teacher Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Supportive School Culture and Teacher Collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucaliuc, M.; Curșeu, P.L.; Muntean, A.F. Does Distributed Leadership Deliver on Its Promises in Schools? Implications for Teachers’ Work Satisfaction and Self-Efficacy. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornito, C. Striking a Balance between Centralized and Decentralized Decision Making: A School-Based Management Practice for Optimum Performance. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Rev. 2021, 3, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, W. Understanding China’s curriculum reform for the 21st century. J. Curric. Stud. 2014, 46, 332–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X. Policy and Practice of the Decentralization of Basic Education in China: The Shanghai Case. Front. Educ. China 2017, 12, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, N.; Sandoval-Hernandez, A. Is Distributed Leadership Universal? A Cross-Cultural, Comparative Approach across 40 Countries: An Alignment Optimisation Approach. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairon, S.; Dimmock, C. Singapore schools and professional learning communities: Teacher professional development and school leadership in an Asian hierarchical system. Educ. Rev. 2012, 64, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Hopkins, D. Distributed leadership and organizational change: Reviewing the evidence. J. Educ. Change 2007, 8, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRue, D.S. Adaptive leadership theory: Leading and following as a complex adaptive process. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed Leadership. In Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration; Leithwood, K., Hallinger, P., Furman, G.C., Riley, K., MacBeath, J., Gronn, P., Mulford, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 653–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H.; Han, X. Higher education governance and policy in China: Managing decentralization and transnationalism. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID 19—School leadership in disruptive times. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Distributed leadership: A critical analysis. Leadership 2014, 10, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.J.; McNess, E.; Thomas, S.; Wu, X.R.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.Z.; Tian, H.S. Emerging perceptions of teacher quality and teacher development in China. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 34, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ma, Z.; Li, M.; Xie, G.; Hu, W. Authentic leadership: Bridging the gap between perception of organizational politics and employee attitudes in public sector museums. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Cao, C.; Huang, R. Teacher Learning Through Collaboration Between Teachers and Researchers: A Case Study in China. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2023, 21, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xiu, Q. Teacher Professional Collaboration in China: Practices and Issues. Beijing Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 1, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, G.; Kang, C.; Mitchell, I.; Ryan, J. Role of Teacher Research Communities and Cross-Culture Collaboration in the Context of Curriculum Reform in China. In Learning Communities in Practice; Samaras, A.P., Freese, A.R., Kosnik, C., Beck, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUANG, F. Curriculum reform in contemporary China: Seven goals and six strategies. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Hu, X.; Hu, Q.; Liu, Z. A social network analysis of teaching and research collaboration in a teachers’ virtual learning community. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolden, R. Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. IJMR 2011, 13, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y. Towards network governance: Educational reforms and governance changes in China (1985–2020). Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2022, 23, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Yin, H. Teachers’ emotions and professional identity in curriculum reform: A Chinese perspective. J. Educ. Change 2011, 12, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S. School culture and teacher job satisfaction in early childhood education in China: The mediating role of teaching autonomy. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2023, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, J. Identifying information friction in teacher professional development: Insights from teacher-reported need and satisfaction. J. Educ. Teach. JET 2022, 48, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Rosseel, Y.; Vlerick, P. Dimensions of distributed leadership and the impact on teachers’ organizational commitment: A study in secondary education. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1745–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, R. The distribution of leadership and power in schools. Br. J. Soc. Educ. 2005, 26, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Wilson, S.M. Principals’ Efforts to Empower Teachers: Effects on Teacher Motivation and Job Satisfaction and Stress. Clear. House 2000, 73, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Rosseel, Y. The relationship between the perception of distributed leadership in secondary schools and teachers’ and teacher leaders’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2009, 20, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.; Dikkers, S. Framing Feedback for School Improvement Around Distributed Leadership. Educ. Adm. Quart. 2016, 52, 392–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppi, P.; Eisenschmidt, E.; Jõgi, A. Teacher’s readiness for leadership—A strategy for school development. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Z.S.; Hochwarter, W.A. Perceived organizational support and performance: Relationships across levels of organizational cynicism. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Devos, G.; Valcke, M. The relationships between school autonomy gap, principal leadership, teachers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Rhoades Shanock, L.; Wen, X. Perceived Organizational Support: Why Caring About Employees Counts. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 7, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Perinelli, E.; Mariani, M.G. The effect of individual, group, and shared organizational identification on job satisfaction and collective actual turnover. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J. Exploration of transformational and distributed leadership. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 19, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.H. The effects of distributed leadership on teacher professionalism: The case of Korean middle schools. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M.Ş.; Gümüş, S.; Liu, Y. Does school leadership matter for teachers’ classroom practice? The influence of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on instructional quality. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 32, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Dochy, F.; Raes, E.; Kyndt, E. Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teach. Teach. 2019, 25, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoban, Ö.; Atasoy, R. Relationship between distributed leadership, teacher collaboration and organizational innovativeness. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratsch-Hines, M.; Pico, D.; Loch, T.; Osarenkhoe, K.; Viafore, R.; Faiello, M.; Pullen, P. Using professional learning to foster distributed leadership and equity of voice and promote higher quality in Early childhood education. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 49, 1131–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.M.; Pun, W.H.; Chung, K.S. Influence of teacher collaboration on job satisfaction and student achievement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 67, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egodawatte, G.; McDougall, D.; Stoilescu, D. The effects of teacher collaboration in Grade 9 Applied Mathematics. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2011, 10, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webs, T.; Holtappels, H.G. School conditions of different forms of teacher collaboration and their effects on instructional development in schools facing challenging circumstances. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2018, 3, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B. Teacher collaboration: Good for some, not so good for others. Educ. Stud. 2003, 29, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, F.R.; Amiruddin, A.; Idkhan, A.M. Integrated Leadership Effect on Teacher Satisfaction: Mediating Effects of Teacher Collaboration and Professional Development. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2023, 22, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J.; Shapka, J.D.; Perry, N.E. School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, I.A.; Kass, E. Teacher self-efficacy: A classroom-organization conceptualization. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, E.; Li, J. What is the value essence of “double reduction” (Shuang Jian) policy in China? A policy narrative perspective. Educ. Philos. Theory 2023, 55, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Pu, R.; Hao, Y. How can an innovative teaching force be developed? The empowering role of distributed leadership. Think. Skills Creat. 2024, 51, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Van Keer, H. The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Teachers’ Organizational Commitment: A Multilevel Approach. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 103, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Risku, M.; Collin, K. A meta-analysis of distributed leadership from 2002 to 2013: Theory development, empirical evidence and future research focus. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasci Sonmez, E.; Cemaloglu, N. Distributed leadership, self-awareness, democracy, and sustainable development: Towards an integrative model of school effectiveness. Educ. Res. Eval. 2024, 29, 538–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y.O.; Ng, L.P.; Ai Na, S.; Tan, C.E. The role of teachers’ self-efficacy between trust and organisational citizenship behaviour among secondary school teachers. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Lee, J. EFL teachers’ self-efficacy and teaching practices. ELT J. 2018, 72, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M. Distributed Leadership and Teacher’Self-Efficacy: The Case Studies of Three Chinese Schools in Shanghai. Master’s Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylän, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoglu, M.E.; Cansoy, R.; Parlar, H. Examining Relationship between Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Bulut, M.B.; Yildiz, M. Predictors of teacher burnout in middle education: School culture and self-efficacy. Stud. Psychol. 2021, 63, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, J.; Retell, J. Teaching Careers: Exploring Links Between Well-Being, Burnout, Self-Efficacy and Praxis Shock. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Steca, P.; Malone, P.S. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I.; Moè, A. What makes teachers enthusiastic: The interplay of positive affect, self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 89, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenbourg, P. Collaborative-learning: Cognitive and computational approaches. Comput. Educ. 2000, 35, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkosky, K. Self-Efficacy: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Forum 2009, 44, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.I.; O’Rourke, E.; O’Brien, K.E. Extending conservation of resources theory: The interaction between emotional labor and interpersonal influence. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2014, 21, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.H.; Kong, C.A. Teacher Collaborative Learning and Teacher Self-Efficacy: The Case of Lesson Study. J. Exp. Educ. 2012, 80, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.W.; Yendol-Hoppey, D.; Jacobs, J. High-Quality Teaching Requires Collaboration: How Partnerships Can Create a True Continuum of Professional Learning for Educators. Educ. Forum 2015, 79, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, Y.J.A.; Alsarayreh, R.; Ajlouni, A.A.A.; Eyadat, H.M.; Ayasrah, M.N.; Khasawneh, M.A.S. An examination of teacher collaboration in professional learning communities and collaborative teaching practices. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 2023, 10, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Technical Report; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; p. 21. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS-Starting-Strong-2018-Technical-Report.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Technical Report; OCED: Paris, France, 2019; p. 99. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS_2018_Technical_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Klassen, R.M.; Chiu, M.M. Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M. Influence of age group on job satisfaction in academia. SEISENSE J. Manag. 2019, 2, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yipeng, T.; Jiali, H.; Qiong, L. Teachers’s Job Satisfaction and Its Influencing Factors in High-Performing Four Asian Countries: Multi-level Analysis Based on TALIS 2013 Data. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.S.; Lepper, M.R. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M. Confucian Culture and Democratic Values: An Empirical Comparative Study in East Asia. J. East. Asian Stud. 2024, 24, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, N.; Sandoval Hernandez, A. Improving cross-cultural comparability: Does school leadership mean the same in different countries? Educ. Stud. 2024, 50, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.F. The Need for Cross-Cultural Exploration of Teacher Leadership. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 6, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Xia, J. Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 92, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, H.; Sadjadi, B.; Afzali, M.; Fathi, J. Self-efficacy and emotion regulation as predictors of teacher burnout among English as a foreign language teachers: A structural equation modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 900417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, C. Self-efficacy for instructional leadership: Relations with perceived job demands and job resources, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and motivation to quit. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 1343–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong-Mai, N.; Terlouw, C.; Pilot, A. Cooperative learning vs Confucian heritage culture’s collectivism: Confrontation to reveal some cultural conflicts and mismatch. Asia Eur. J. 2005, 3, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Stronge, J.H. Chinese middle school teachers’ preferences regarding performance evaluation measures. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2016, 28, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairon, S.; Tan, C. Professional learning communities in Singapore and Shanghai: Implications for teacher collaboration. Compare 2017, 47, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolleck, N.; Schuster, J.; Hartmann, U.; Gräsel, C. Teachers’ professional collaboration and trust relationships: An inferential social network analysis of teacher teams. Res. Educ. 2021, 111, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Molina-Fernández, E.; Fernández-Batanero, J.M. Mapping teacher collaboration for school success. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 32, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z. The moderating role of teacher collaboration in the association between job satisfaction and job performance. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Werblow, J. The operation of distributed leadership and the relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction of principals and teachers: A multi-level model and meta-analysis using the 2013 TALIS data. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 96, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A. Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation. Science 2006, 314, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | RMR | NFI | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Model | 9357.268 | 428 | 0 | 21.863 | 0.074 | 0.843 | 0.877 | 0.037 | 0.872 | 0.866 |

| Model 1 | 16,660.335 | 431 | 0 | 38.655 | 0.099 | 0.747 | 0.776 | 0.053 | 0.772 | 0.759 |

| Model 2 | 17,419.515 | 431 | 0 | 40.417 | 0.102 | 0.747 | 0.766 | 0.059 | 0.761 | 0.747 |

| Model 3 | 18,168.513 | 431 | 0 | 42.154 | 0.104 | 0.681 | 0.756 | 0.178 | 0.751 | 0.736 |

| Model 4 | 25,977.731 | 433 | 0 | 59.995 | 0.125 | 0.608 | 0.648 | 0.179 | 0.644 | 0.622 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DL | 3.052 | 0.602 | 1 | |||

| 2. TC | 3.812 | 0.969 | 0.334 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. TSE | 3.311 | 0.542 | 0.296 *** | 0.297 *** | 1 | |

| 4. TJS | 2.900 | 0.465 | 0.492 *** | 0.254 *** | 0.266 *** | 1 |

| Path Description | Effect Size (β) | 95% CI | Proportion of Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Total Effect | 0.442 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 100% |

| Direct Effect | 0.401 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 90.12% |

| Indirect Effect | 0.041 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 9.88% |

| DL→TC→TJS | 0.013 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 2.47% |

| DL→TSE→TJS | 0.019 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 5.56% |

| DL→TC→TE→TS | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.85% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, X.; Chu, Z. The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Chinese Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Chain Mediation of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040507

Fan X, Chu Z. The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Chinese Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Chain Mediation of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040507

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Xiaodong, and Zuwang Chu. 2025. "The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Chinese Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Chain Mediation of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040507

APA StyleFan, X., & Chu, Z. (2025). The Influence of Distributed Leadership on Chinese Teachers’ Job Satisfaction: The Chain Mediation of Teacher Collaboration and Teacher Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040507