1. Introduction

In the United States, dementia affects approximately 10% of people aged 65 years and older [

1]. Despite the prevalence of this chronic disease, significant gaps persist in the care provided to individuals living with dementia [

2,

3]. A growing research base in primary care has documented complexities in supporting people living with dementia and their caregivers, including the lack of clinical workflows for dementia care with electronic health records (EHR) [

4,

5,

6], fragmented or absent healthcare provider and clinic staff education [

2,

3,

5,

7,

8,

9,

10], and missing interprofessional linkages and care management support [

2,

4,

5,

6,

8,

11,

12,

13]. In one response to these gaps, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Age-Friendly framework focuses providers on evidence-based high-quality care that addresses the “4Ms”: What Matters, Medication, Mentation, and Mobility.

1.1. Clinical Workflows for Dementia Care

Primary care providers face challenges in delivering uniform or adequately tailored care to patients with dementia, particularly due to time constraints or the demands of managing other patients [

2,

3,

9,

14]. To address these challenges, the implementation of structured care models and/or workflows are identified as beneficial in the research [

4,

5,

6]. Care for older adults can be streamlined through the implementation of workflows as well [

5]. Workflows, such as EHR flow sheets and prompts integrated into patient charts, can be practical in highlighting key signs and symptoms that guide physicians toward an accurate diagnosis of dementia and help formulate appropriate action steps [

4]. Ganz et al. (2008) found that structuring care models to support providers is valuable in under-resourced primary care settings that lack access to experts in the field [

5]. Although evidence supports the effectiveness of implementing workflows and care models [

4,

5,

6], replicability has been limited due to financial constraints, the need for provider training, and the time required for implementation [

6].

1.2. Healthcare Provider and Clinic Staff Education

Staff education and training for primary care providers and clinic staff are key elements to optimize the care of people living with dementia [

2,

5,

7,

8,

9]. Research highlights a clear need for comprehensive education in dementia care for primary care providers [

2,

7], including further training in conducting and evaluating cognitive screenings [

10]. Likewise, Ganz et al.) highlight the need for increased education for the clinic staff in primary care to facilitate more comfortable interactions with vulnerable older adults [

5]. Training clinical staff in addition to primary care providers is recommended [

5,

9]. However, although educational interventions may be somewhat effective in improving detection of dementia, these interventions do not appear to increase adherence to dementia guidelines [

15]. Additional training needs include supporting patients with dementia in advanced care planning [

9], addressing the mental health impacts of a dementia diagnosis, reducing the stigma surrounding brain change and dementia [

10], and recognizing the benefits of early diagnosis [

3].

1.3. Interprofessional Linkages and Care Management Support

Older adult health is uniquely complex, often involving interrelated and multifaceted needs [

16] compounded by chronic conditions such as dementia [

17]. A single-provider approach poses challenges in meeting these needs, whereas a multidisciplinary team provides enhanced benefits through more comprehensive care [

4,

5,

6,

8,

11,

12,

13]. Multidisciplinary teams, which can include primary care providers, nurse practitioners, clinicians, and care managers, have been shown to significantly improve patient outcomes in dementia care programs, including fewer hospitalizations, reduced emergency department visits, and a reduction in long-term care admissions [

8]. These effects are attributed to the collaborative care model, where the physician retains responsibility for the clinical aspects of care, while other members of the care team focus on addressing mental health, social well-being, and caregiver support [

8]. Evidence demonstrates that a collaborative care model improves health outcomes for people living with dementia [

4,

5,

8,

11,

12] including reducing symptom severity, enhancing quality of life, and reducing financial burden [

12]. Similarly, the Chronic Care Model (CCM) emphasizes the positive impact of interdisciplinary teams and community resources in improving chronic disease management [

18].

In particular, the involvement of a care manager or primary care liaison has been found to facilitate ongoing care by connecting patients to community organizations and essential resources such as Area Agencies on Aging, support groups, senior care, and other forms of assistance [

8,

11,

19,

20]. These connections enhance outcomes for both patients and caregivers by improving neuropsychological symptoms of dementia, reducing hospital admissions, and decreasing caregiver burden [

11,

19], while promoting cost-neutral care [

8]. Care managers play a role in connecting patients to community organizations. These connections foster social engagement, peer connections, and physical activity, thereby supporting the emotional and physical well-being of individuals living with dementia [

21]. Additionally, primary care provider referrals enhance the likelihood that people living with dementia and/or their caregivers will engage in post-appointment support, particularly, with a case manager [

6,

22]. Despite these findings, the integration of care managers into dementia care teams has been limited by the lack of case managers in primary care settings [

20].

Our project attempted to address many barriers noted in the research literature. Most notably, the project introduced another discipline, care management from the Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), and a structured, EHR-based collaborative care model, into the primary care setting. In this role, the bachelor’s prepared AAA care coordinator was embedded in the clinic with access to the EHR and was available as a referral source for providers, linking patients and caregivers to education and support. The authors examined the change in the number of patients and caregivers who received education and support after the adoption of the dementia workflow in three primary care clinics. While provider utilization of the AAA care coordinator increased overall, AAA care coordinators remained underutilized with respect to caregiver dementia education and support.

2. Materials and Methods

Our mid-western public university was awarded a five-year Health Resources and Services Administration Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP) in 2019. A major objective was to transform primary care into age-friendly care by applying the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health System framework. Within the first fiscal year, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted healthcare to such as extent that GWEPs had to shift focus to other objectives, such as the education of future health professionals, until they could return to the primary care setting. Our project did not implement the clinic-based intervention in dementia care until spring 2023. With the project concluding in a little more than a year later, the team planned a modest analysis of results across the three participating clinics, hoping to glean some implementation lessons and perhaps identify some promising data post-intervention.

The GWEP onboarded a primary care clinic in each of the first three years of the initiative. Working with the health system partner, the GWEP selected three clinics operating in medically underserved geographic areas. The GWEP also selected two clinics from different rural counties, one of which was a CMS-designated Rural Health Clinic (RHC).

Table 1 provides demographic information about each clinical setting.

The urban clinic, Clinic A, was the first of the three to join the initiative. Clinic B, the larger of the two rural clinics, and the RHC, followed in the second grant year. The third clinic, Clinic C, represented a smaller, rural clinic. The dementia care intervention was implemented nine months after Clinic C formally joined the GWEP and the clinic’s AAA care coordinator had begun responding to provider referrals of patients.

2.1. Clinical Workflow Development and Implementation

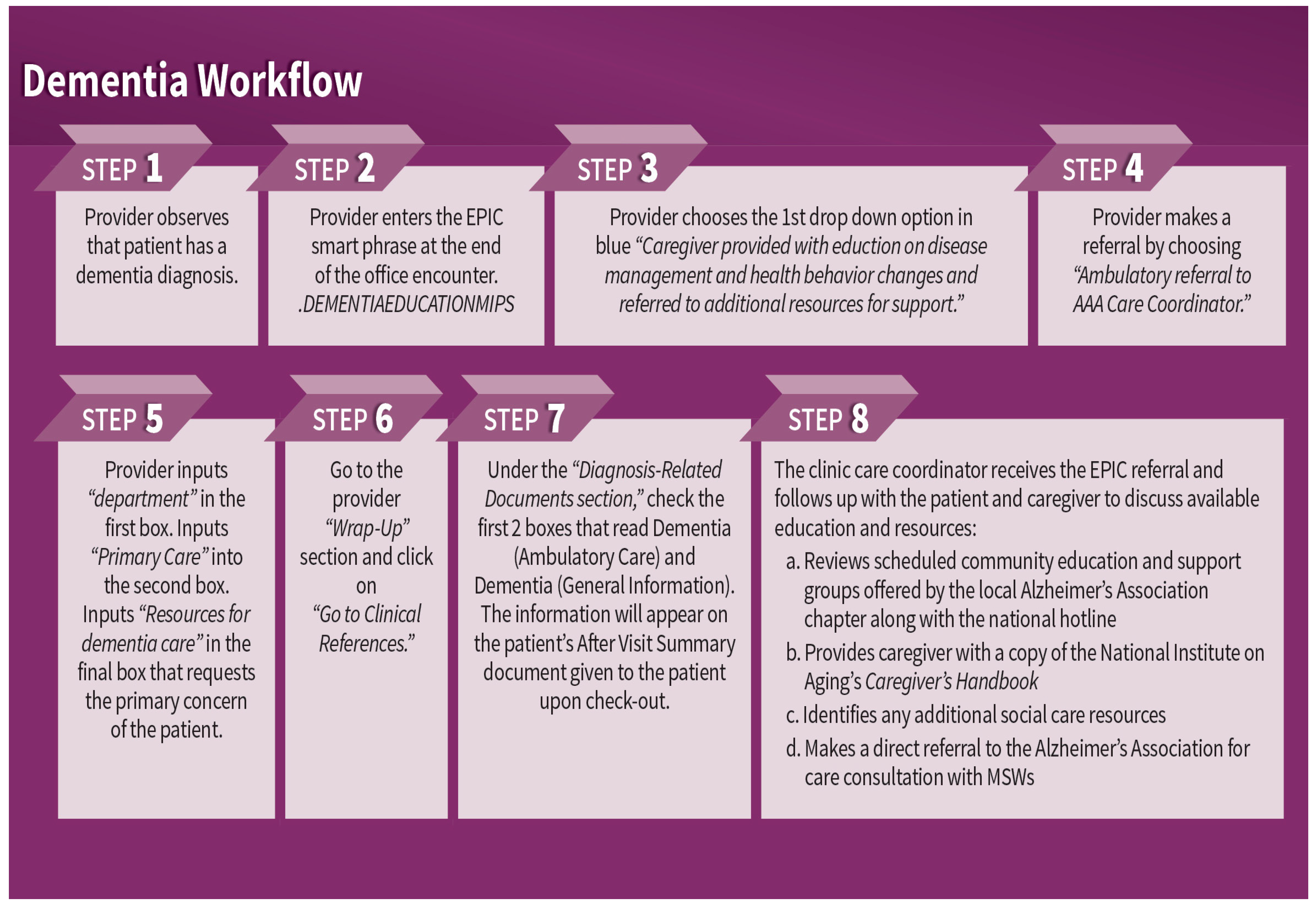

To address mentation, an interdisciplinary team of staff working at the health system, AAA care coordinators, and university educators, with contributions from Alzheimer’s Associations partners, developed a clinical workflow to help ensure that patients diagnosed with dementia and their caregivers were receiving education and referrals to community resources. The clinical workflow was supported by step-by-step instructions for providers that populated the After Visit Summary with patient education on dementia and guided the generation of an EHR-based referral to the AAA care coordinator embedded in the clinic. Refer to

Figure 1 for a graphical representation of the clinical dementia workflow implemented in GWEP primary care clinics. At each clinic, an Age-Friendly Champion provider was also identified to help promote provider awareness of age-friendly care practice changes, such as those outlined in

Figure 1.

The clinical workflow was also supported by a detailed protocol for AAA care coordinators to follow when receiving a patient referral from a provider. The protocol guided AAA care coordinators to offer time for caregivers and patients to ask questions about the dementia diagnosis. It also walked care coordinators through state-funded caregiver programs and how to access additional education and support from the local chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association and the national Alzheimer’s Association Helpline.

The healthcare partner’s quality improvement staff trained providers, practice managers, and AAA care coordinators at each of the clinics on the new clinical workflow and accompanying EHR instructions. Key components shared with providers included information related to (a) talking to patients and caregivers about dementia diagnoses, (b) making EHR-based information about dementia available to patients and caregivers as a part of the After Visit Summary, and (c) referring the caregiver to the AAA care coordinator. In addition to providing one clinic-based workflow training for providers, the project also offered follow-up sessions with clinic practice managers and annual health system training on dementia care, delivered by the Alzheimer’s Association. During two grant years, the Alzheimer’s Association training was supplemented by medical content delivered by physicians practicing at the health system. Open to all health system employees, annual training was designed to raise general awareness about project goals in the three clinics and the resources available to the health system. Additionally, the healthcare partner’s quality improvement staff coached the AAA care coordinators to (a) provide information and support to caregivers in accessing and navigating local Alzheimer’s Association resources, (b) make a direct referral to the Alzheimer’s Association for free care consultation, and (c) distribute a free copy of Caring for A Person with Alzheimer’s Disease (National Institute on Aging, January 2019) to each caregiver.

2.2. Project Data Collection

In acknowledgement of the busy health system environment, and its substantial resources already committed to data collection, monitoring and reporting, the research team conducted a retrospective evaluation of the dementia care intervention. The evaluation utilized secondary data sources to examine whether dementia care interventions had impacted the primary care delivered to patients living with dementia and their caregivers. The university’s institutional review board determined that the project did not meet the definition of human subjects as set forth by Federal Regulations 45 CFR 46. A HIPAA Limited Data Set agreement was established and monitored by the health system’s research oversight and privacy board.

The retrospective evaluation utilized several secondary data sources from the health system to examine clinical outcomes. These sources are presented in

Table 2 and are described in further detail below.

The health system’s quality improvement team extracted calendar-year EHR data for the period 2019–2024 to provide information on the volume of GWEP clinic patient populations and annual clinical visits. Utilizing CMS specifications, the quality improvement team also used EHR data to calculate the denominator of MIPS 288. The MIPS 288 denominator offered a standardized and validated measurement of the patient population living with dementia across GWEP clinics, ensuring that the same exclusionary and inclusionary criteria were used [

23]. Because the quality improvement team already had a significant CMS MIPS reporting program, they found this role a relatively light burden. Given that data represented aggregated counts, the research team did not have access to other related characteristics of patients living with dementia, such as the date of dementia diagnosis or an identified healthcare representative in the medical chart.

AAA care coordinator service records were also gathered. These provided information on the total number of patients referred to care coordinators each year, the number of patients and/or caregivers who received some form of assistance from a care coordinator, and the number of caregivers who received dementia-specific education and support referrals. AAA care coordinators were asked to double-enter records of patient services, once in a standardized spreadsheet, followed by a provider note in the patient medical chart.

Table S1 defines the fields contained within the care coordinator tracking spreadsheet.

Table S2 presents the referral options that were available to select and the referral type that was associated with that option. As shown in

Table S1, care coordinators recorded each patient interaction, noting whether the interaction reflected a new provider referral or was a follow-up contact with a previously referred patient and what assistance was provided during the interaction, such as assistance with food stamps or a Medicaid application or a referral to the Meals on Wheels program or the Alzheimer’s Association. See

Tables S1 and S2 in Supplementary Materials for a complete list of the variables contained in the spreadsheet.

Care coordinators stripped patient identifiers such as name and Medical Record Number before uploading encrypted spreadsheets to a secure cloud-based file directory. A HIPAA Limited Data Set agreement allowed the data set to retain birth year, residential ZIP code, and date of care coordinator contact attempt. Only patient-level data stripped of patient identifiers were available from care coordinators; therefore, the research team was not able to link patient data across different care coordinator interactions for statistical analysis.

Data sources presented another challenge, even to descriptive analysis. MIPS methodology tied data measurement to the health system’s annual measurement schedule based on the calendar year. In contrast, care coordinator data were reported on the grant year cycle, 1 July through 30 June, reflecting the annual cycle of GWEP programmatic activities and the onboarding of clinics.

Table 3 shows how the measurement period of data sources differed, depending on whether the source was the AAA care coordinator services form or MIPS measurement.

Because MIPS data on the number of patients living with dementia straddled two grant years, it was not possible to know the precise number of patients living with dementia and their caregivers who were not served each year. Care coordinator data generally matched the grant year, except for the first year each clinic joined due to the time needed to train AAA care coordinators in the EHR and establish referral processes. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted early referral work at Clinic A and appeared to contribute to a very slow start-up of care coordinator services at Clinic B during the second grant year. Potential analyses were hamstrung by available data sources and the sustained effects of COVID-19 on healthcare delivery systems during the initiative.

3. Results

To understand clinical settings of the GWEP dementia intervention, the research team examined data on the patient population of older adults (aged 65 and older) served by each clinic. As

Table 4, below, shows, the older adult population made up a significant proportion of each clinic’s total patient population. Even so, the proportion of annual clinic visits made by older adults was even larger than that of the population: older adults at Clinic A made up 44% of the patient population and nearly 52% of annual clinic visits; similarly, older adults made up 29% and 27%, respectively, of Clinic B and Clinic C patient populations and 35% of annual clinical visits.

The sizeable older adult patient populations and clinic locations in medically underserved areas made these clinics good candidates for GWEP interventions, designed to improve the quality of healthcare of older adults.

Next, the research team wanted to understand more about the prevalence of dementia at participating clinics.

Table 5 shows the number of patients diagnosed with dementia and with at least one clinical visit during 2023. Because these data were derived from the denominator of the dementia MIPS measure, this number reflects all patients with dementia, not just those aged 65 and older.

Across the three clinics, there were 304 patients with a medical diagnosis of dementia. Because this number includes patients aged 64 and younger with a medical dementia diagnosis, the percentage of each clinic’s 65-and-older population was less than the figure estimates.

Comparing the expected number of patients living with dementia at each clinic, the data suggested that the patient population with a medical diagnosis of dementia was likely an underrepresentation of the actual patient population living with dementia. At Clinic A and B, patient populations diagnosed with dementia represented approximately half of what would be expected based on national estimates for patients aged 65 and older, alone.

The number of caregivers who received education and referrals to community support was even smaller than the diagnosed population, as reflected in

Table 6. During the 5 years of the GWEP initiative, AAA care coordinators provided dementia education and referrals to support for 88 caregivers of patients living with dementia. Breaking these unduplicated referral numbers down by clinic showed that far fewer than half of diagnosed patients were assisted by AAA care coordinators.

To assess whether there had been an increase in patient referrals following the implementation of the dementia intervention at clinics, the research team disaggregated referral data by year at each clinic (

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9).

The data in

Table 7 indicated that each year, patients living with dementia made up a small fraction of the patients that providers referred to AAA care coordinators. Fourty-two caregivers, or 65.6% of those assisted, received assistance prior to the intervention year. Another 22 caregivers received assistance during the intervention year and the final year of the initiative. During this time, the share of patient referrals made up by medically diagnosed dementia patients declined.

Similar patterns were observed in Clinics B and C. At Clinic B, the only provider referrals of patients with dementia came before the dementia clinical workflow was introduced.

The dementia care intervention did not increase the referral of patients diagnosed with dementia at Clinic C either.

Altogether, 54 of the 88 caregivers who received assistance during the GWEP received it before the intervention was implemented, with the remaining 34 in the last two years of the initiative. Seventeen caregivers received education and referrals to support during the intervention year and again in the final year. During the same period, provider referrals of patients increased, translating into a decrease in the percentage of patients diagnosed with dementia represented in annual patient referrals.

4. Discussion

Results from this study suggested that the intervention did not take hold as intended. After the introduction of the clinical workflow for patients diagnosed with dementia, clinic providers did not take advantage of most clinical encounters with these patients to make a referral to the AAA care coordinator. Yet, 1714 patients received referrals to the AAA care coordinator and received assistance accessing healthcare and other health-related social needs during the five-year initiative. Furthermore, 450 or 26.25% of referred patients were connected to an AAA care coordinator for assessment and program eligibility for a range of services including home care and home health. This meant additional opportunities for caregiver engagement and referrals to support as patients entered the agency’s service population. Thus, patient connections to the AAA agency would offer another opportunity to identify cognitive challenges and caregiver needs.

Across the three clinics, the number of patients referred to AAA care coordinators by providers increased substantially in the year that the dementia workflow was introduced. This increase may have reflected a new awareness of providers regarding the vulnerabilities of older adults, following COVID-19. However, this increase did not convert to more patients and caregivers receiving dementia education and referrals to support. The number of patients with a dementia diagnosis and a medical encounter at either of the three clinics who were not referred to the care coordinator is striking. A gap between the number of patients living with dementia seen each year and those provided with a referral persisted during the project. This gap could be partially attributed to the fact that dementia symptoms are broad and go beyond memory loss to include multiple types of cognitive changes such as communication deficits, cognitive processing, difficulty with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

The project team anticipated that the integration of the AAA care coordinator into the dementia clinical workflow would promote its adoption and eventual institutionalization, consistent with the underpinnings of the CCM and its emphasis on linkages between the health and social needs of patients [

5]. Although dementia workflow training was delivered to providers and office staff in three primary care clinic sites, the data underscore the limitations of one-time or infrequent training of providers, without more rigorous intervention to support clinical practice as indicated in the literature [

5,

9]. This finding aligns with Perry et al., who highlighted that the length and frequency of educational interventions affected the depth of understanding that family practitioners gained regarding dementia identification [

15]. Additionally, these data suggest the need for ongoing provider education regarding the benefits of early detection as well as continued reinforcement of the value-add in utilizing the case manager to support people living with dementia and their caregivers in primary care [

11].

Finally, it is worth noting that the stigma associated with dementia and reluctance on the part of the provider to screen [

2], refer the patient to a neurologist for diagnosis, or offer support in managing a diagnosis of dementia may have played a factor in the underrepresented number of provider referrals specific to dementia. Project results appear to suggest that a more comprehensive intervention is needed, one that addresses both patient and provider concerns about a potentially stigmatizing diagnosis.

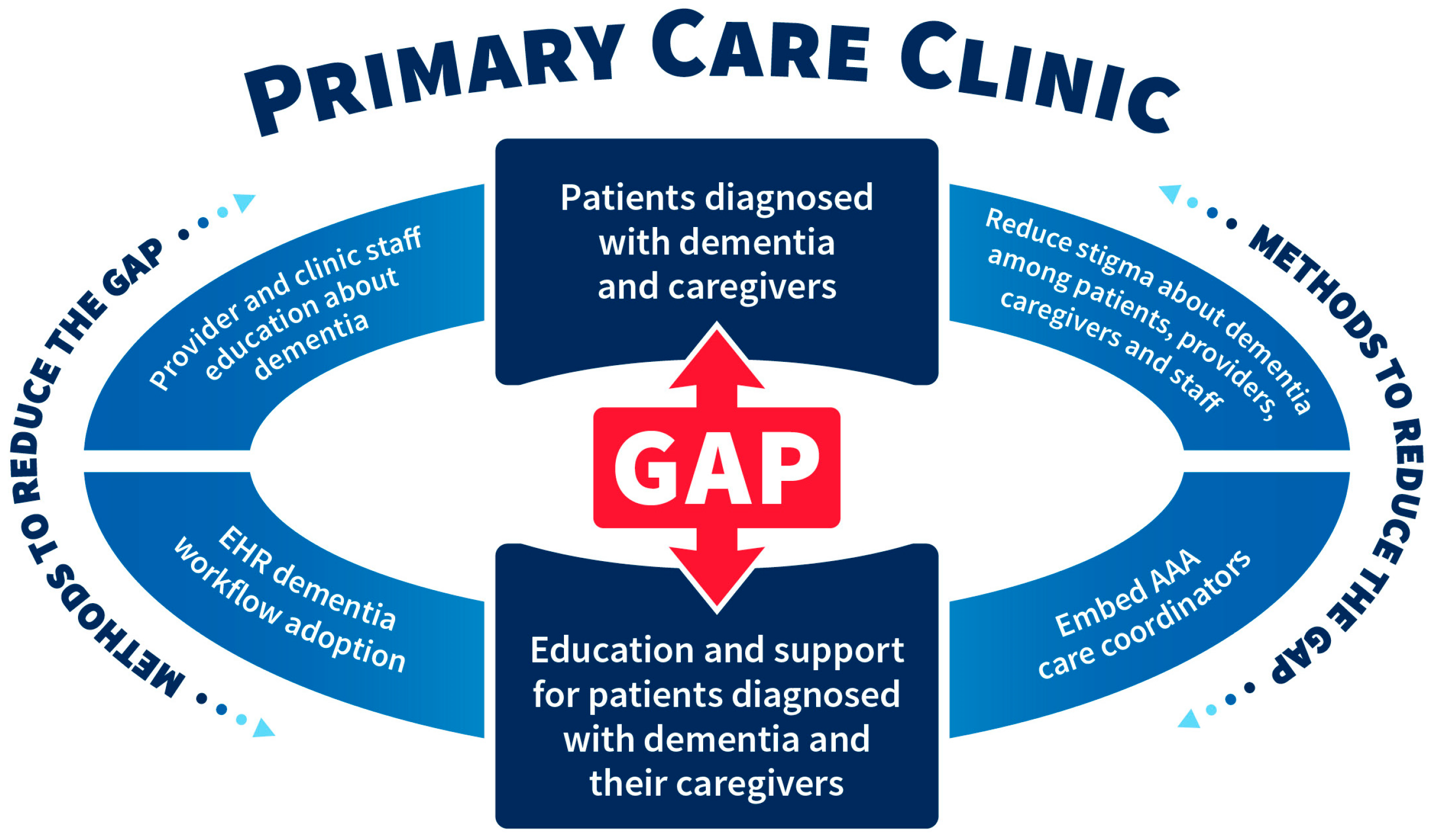

Results from this descriptive study point to the complexities that exist in managing dementia in primary care in two areas: (a) the gap between patients diagnosed with dementia and their caregivers and those who were provided education for support; and (b) the need for ongoing provider education in dementia care practice, which is consistent in the literature [

5,

9]. Additionally, the research raises questions about the role that stigma plays in dementia diagnosis as well as the role of competing provider demands. The schematic diagram in

Figure 2 highlights the gap referenced above and lists methods to reduce this gap to include a) increased provider and clinic staff education about dementia, (b) reduced stigma about dementia among patients, providers, caregivers, and staff, (c) embedded AAA care coordinators in primary care, and (d) the promotion of electronic health record dementia workflow adoption.

Despite the limited number of patients and caregivers benefiting from the dementia intervention, this study adds to the health and human service integration literature [

24]. Primary care providers utilized the embedded AAA care coordinator to improve patient care, demonstrating the feasibility of addressing health-related social needs in the primary care clinical setting and supports. During the initiative, 1714 patients from the three clinics were assisted in advance care planning, referrals to evidence-based health programs, and referrals or assistance accessing community-based resources. In this context, the CCM becomes an important framework, as it encourages interdisciplinary collaboration to direct care improvement for chronic conditions [

18], like dementia. This model’s focus on integrating quality care with community support aligns with the integration of the AAA care coordinators in primary care settings.

5. Conclusions

This modest research project helps illuminate some of the complexities that exist in managing dementia care in primary care. Uncovering complexities in managing dementia is challenging in health services research where there is typically a wealth of existing data, which makes primary data collection a difficult case to make to administrators. Because of this, significant technical expertise and health system partnership is needed to identify the measures approximating study variables. Furthermore, the sheer volume of data requires significant technical expertise to access and manipulate for new variable construction and aggregation.

Despite its modest scope, the study also suggests that Area Agencies on Aging and primary care clinics can develop partnerships that result in better primary care for the aging population. The research team looks forward to additional development and testing of partnership models between AAAs and primary care, as the healthcare field continues to explore interventions that integrate medical and social care.

Finally, the project outcomes lend insight into implications for clinical practice, state health policy, and future research. The project raises some important questions about efforts to make primary care best practice the easy choice in EHR workflows. The research team found that while workflows can help integrate healthcare delivery by multidisciplinary teams, workflow development and adoption, in and of itself, is an insufficient strategy for improving dementia care. Additional strategies are needed. These might include state mandated dementia training hours for annual license requirements for providers. Other future strategies might embed artificial intelligence in medical software to prompt dementia smart phrases, referrals, and educational handouts. Creating certificate programs and/or mini fellowships for primary care providers who have a strong interest in eldercare also may help with the hesitancy to address dementia. Designation of one to two of these specially trained providers in a group practice may enhance care for elders in rural or urban communities.

Moving forward, the GWEP project will continue to embed AAA care coordinators in primary care clinics and support this integration through EHR-based workflows to connect patients and caregivers to valuable community resources and to prompt providers in decision-making. However, a Geriatric Provider Support Model will be implemented to support this work, making training, not the EHR workflow, the foundation of new care practices. Clinic adoption and implementation of the model will be aided by dedicated mentoring and support roles of a nurse practitioner and medical office assistant. In addition, more attention will be given to the national efforts of the Alzheimer’s Association in defining dementia workflows for primary care.

6. Study Limitations and Contributions

Given the many limitations of the data, and the challenges of implementing any intervention in the post-COVID-19 period, statistical analyses comparing the time periods before and after intervention implementation were neither feasible nor appropriate. However, the research team still believed there was value in contextualizing its work and examining patterns descriptively, given growing research interest in effective dementia care intervention. Positive outcomes were limited to the relatively few patients and caregivers who received assistance and appeared to be attributable to the AAA care coordinators embedded in primary care clinics, not other aspects of the intervention, namely, the clinical workflow, which had promised to guide providers in referring patients diagnosed with dementia and their caregivers to education and community resources. Barriers to accessing dementia education and support remained.

Despite limitations, the study highlights some of the implicit challenges of introducing dementia care interventions, even when the burden to clinical teams is at the forefront of the intervention’s design. This intervention targeted only patients diagnosed with dementia; as research literature has suggested, this is likely only a portion of the patient population needing these resources. Furthermore, the intervention required providers to make a patient referral; this likely involved an explanation for the referral and the confronting of the diagnosis by both provider and patient. The dementia care intervention at the center of this study had a modest objective, brief education of caregivers and assistance in accessing community resources available to support the patient and the caregiver in living with a chronic disease. The barriers to this project indicate that more systemic health promotion strategies are required to deliver better dementia care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22040506/s1, Table S1: Data fields completed in Area Agency on Aging Care coordinator spreadsheet title; Table S2: Referral options for AAA care coordinator selection and categorization for analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and M.C.E.; methodology, S.L. and M.C.E.; validation, D.E.; formal analysis, S.L.; resources, M.C.E.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L., M.C.E., D.E. and R.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L., M.C.E., D.E. and R.L.; supervision, M.C.E.; project administration,. M.C.E.; funding acquisition, M.C.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Health Resources Services Administration—Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program-grant number [U1QHP33084]. The University of Southern Indiana Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $3.7 million with 0% percentage financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor are an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern Indiana (protocol codes 2020-103-NH, effective 30 April 2024, and 2022-053-NH, effective 17 December 2021) determined that the project did not meet the definition of human subjects research according to Federal Regulations 45 CFR 46 and did not require IRB review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article contain private health information and cannot be made publicly available. Data inquiries should be directed to Mary C. Ehlman.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Julie Dingman, MHA, BSN, Vice President of Ambulatory Practices, Chief Operating Officer Deaconess Clinic, for her review and contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results. Della Evans is employed by the Deaconess Health System, which operates primary care clinics that were the subject of the study.

References

- Kramarow, E. Diagnosed Dementia in Adults Age 65 and Older: United States, 2022; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024; p. 203. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr203.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Bradford, A.; Kunik, M.E.; Schulz, P.; Williams, S.P.; Singh, H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2009, 23, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcour, V.G.; Masaki, K.H.; Curb, J.D.; Blanchette, P.L. The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 2964–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Le Berre, M.; Rojas-Rozo, L.; McAiney, C.; Ingram, J.; Lee, L.; Vedel, I. Improving dementia care: Insights from audit and feedback in interdisciplinary primary care sites. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, D.A.; Fung, C.H.; Sinsky, C.A.; Wu, S.; Reuben, D.B. Key elements of high-quality primary care for vulnerable elders. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 2018–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, D.B.; Evertson, L.C.; Jackson, S.R.; Epstein, L.G.; Spragens, L.H.; Haggerty, K.L.; Serrano, K.S.; Jennings, L.A. Dissemination of a successful dementia care program: Lessons to facilitate spread of innovations. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldus, C.F.; Arthur, A.; Dennington-Price, A.; Millac, P.; Richmond, P.; Dening, T.; Fox, C.; Matthews, F.; Robinson, L.; Stephan, B.C.M.; et al. Undiagnosed dementia in primary care: A record linkage study. NIHR Libr. 2020, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, L.A.; Laffan, A.M.; Schlissel, A.C.; Colligan, E.; Tan, Z.; Wenger, N.S.; Reuben, D.B. Health care utilization and cost outcomes of a comprehensive dementia care program for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E.; Noble, N.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Mazza, D.; Bryant, J. Primary care physicians’ perceived barriers to optimal dementia care: A systematic review. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e697–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.; De Lima, B.; Aleksandrova, T.; Sanders, L.; Eckstrom, E. Overcoming barriers to early dementia diagnosis and management in primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 2486–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, A.M.; Ensey, M.R.; Bennett, K.A.; O’Leary, M.P.; Wise-Swanson, B.M.; Verrall, A.M.; Vitiello, M.V.; Cochrane, B.B.; Phelan, E.A. A feasibility study of Primary Care Liaisons: Linking older adults to community resources. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, e305–e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz, H.; Monette, P.; Epstein-Lubow, G.; Smith, L.; Rowlett, S.; Forester, B.P. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: A narrative review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.L.; Hodgson, J.L.; Didericksen, K.W.; Lamson, A.L.; Forbes, T.H. Family-centered primary care for older adults with cognitive impairment. Contemp. Fam. Ther. Int. J. 2022, 44, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideman, A.B.; Ma, M.; de Jesus, A.H.; Alagappan, C.; Razon, N.; Dohan, D.; Chodos, A.; Al-Rousan, T.; Alving, L.I.; Segal-Gidan, F.; et al. Primary care practitioner perspectives on the role of primary care in dementia diagnosis and care. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2336030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.; Drašković, I.; Lucassen, P.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; van Achterberg, T.; Rikkert, M.O. Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: A systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.B.; Sabata, D.; Gibbs, H.; Jernigan, S.; Marchello, N.; Zwahlen, D.; Yang, F.M.; Bhattacharya, R.K.; Burkhardt, C. The SPEER: An interprofessional team behavior rubric to optimize geriatric clinical care. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2021, 44, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.A.; Posner, S.F.; Huang, E.S.; Parekh, A.K.; Koh, H.K. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: Imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H. Chronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effic. Clin. Pract. 1998, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, B.; Goodarzi, Z.; Holroyd-Leduc, J. Optimizing the diagnosis and management of dementia within primary care: A systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.; Rait, G.; Aw, S.; Brunskill, G.; Wilcock, J.; Robinson, L.; Knapp, M.; Hogan, N.; Harrison Dening, K.; Allan, L.; et al. Implementing post diagnostic dementia care in primary care: A mixed-methods systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.; Hart, N.; Henderson, C.; Litherland, R.; Pickett, J.; Clare, L.; IDEAL Programme Team. Developing supportive local communities: Perspectives from people with dementia and caregivers participating in the IDEAL programme. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2022, 34, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menn, P.; Holle, R.; Kunz, S.; Donath, C.; Lauterberg, J.; Leidl, R.; Marx, P.; Mehlig, H.; Ruckdäschel, S.; Vollmar, H.C.; et al. Dementia Care in the General Practice Setting: A Cluster Randomized Trial on the Effectiveness and Cost Impact of Three Management Strategies. Value Health 2012, 15, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicaid and Medicare. Quality ID #288: Dementia: Education and support of caregivers for patients with dementia. 2024 MIPS Clinical Quality Measure Specifications and Supporting Documents. Available online: https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/resource-library (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Fichtenberg, C.; Delva, J.; Minyard, K.; Gottlieb, L.M. Health and human services integration: Generating sustained health and equity improvements. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).