Exploring Middle Ear Pathologies in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Available Evidence and Research Gaps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Sources and Data Charting

2.4. Risk of Bias/Quality of the Selected Studies

3. Results

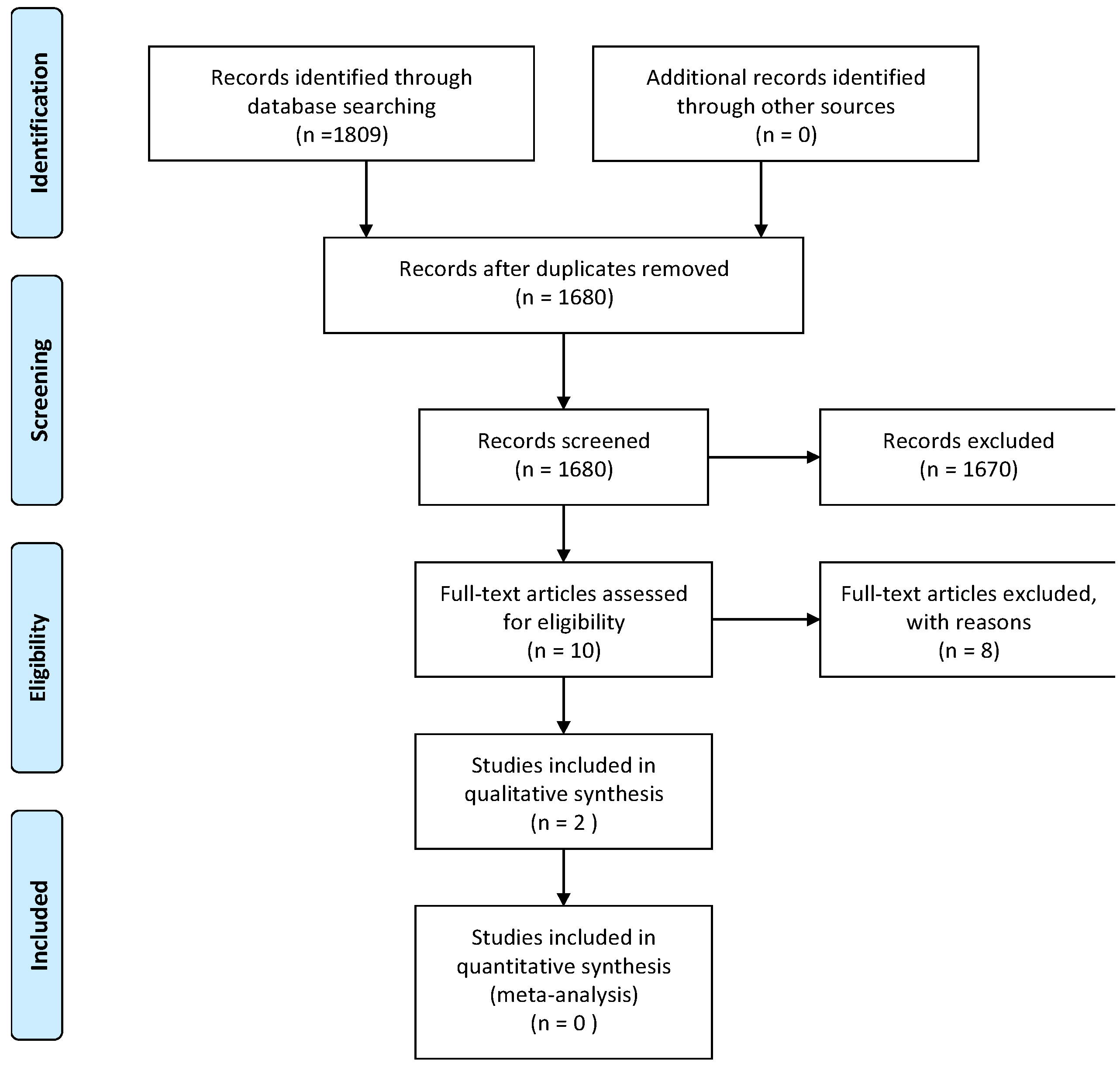

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Prevalence and Nature of Middle Ear Pathologies

3.4. Measures for Identification of Middle Ear Pathologies

3.5. Quality of Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Main Findings

4.2. Limitations and Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Summary of Quality Assessment of the Studies Using the Adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Study | Selection (Max: 4 Stars) | Comparability (Max: 2 Stars) | Outcome (Max: 3 Stars) | Total Score (Max: 9 Stars) | Quality Rating |

| Adebola et al. (2016) [36] | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 8/9 | High |

| Nwosu and Chime (2017) [37] | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7/9 | High |

References

- Banday, M.Z.; Sameer, A.S.; Nissar, S. Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J. Med. 2020, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- da Silva, J.A.; de Souza, E.C.F.; Böschemeier, A.G.E.; da Costa, C.C.M.; Bezerra, H.S.; Feitosa, E.E.L.C. Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and living with a chronic condition: Participatory study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioacchini, F.M.; Pisani, D.; Viola, P.; Astorina, A.; Scarpa, A.; Libonati, F.A.; Tulli, M.; Re, M.; Chiarella, G. Diabetes Mellitus and Hearing Loss: A Complex Relationship. Medicina 2023, 59, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Rawshani, A.; Dabelea, D.; Bonifacio, E.; Anderson, B.J.; Jacobsen, L.M.; Schatz, D.A.; Lernmark, Å. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes around the world in 2021. In IDF Diabetes Atlas; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oleribe, O.E.; Momoh, J.; Uzochukwu, B.S.; Mbofana, F.; Adebiyi, A.; Barbera, T.; Williams, R.; Robinson, S.D.T. Identifying Key Challenges Facing Healthcare Systems in Africa and Potential Solutions. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2019, 12, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mokhele, T.; Sewpaul, R.; Sifunda, S.; Weir-Smith, G.; Dlamini, S.; Manyaapelo, T.; Naidoo, I.; Parker, W.-A.; Dukhi, N.; Jooste, S.; et al. Spatial Analysis of Perceived Health System Capability and Actual Health System Capacity for COVID-19 in South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2021, 14, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Han, K.D.; Park, Y.-M.; Yun, J.-S.; Kim, K.; Bae, J.-H.; Kwon, H.-S.; Kim, N.-H. Diabetes Mellitus in the Elderly Adults in Korea: Based on Data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2019 to 2020. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 643–652. [Google Scholar]

- Animaw, W.; Seyoum, Y. Increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a developing country and its related factors. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187670. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, A.A.; Lepe, A.; Wild, S.H.; Jackson, C. Diabetes comorbidities in low- and middle-income countries: An umbrella review. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 04040. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, A. Know the signs and symptoms of diabetes. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 140, 579–581. [Google Scholar]

- Chentli, F.; Azzoug, S.; Mahgoun, S. Diabetes mellitus in elderly. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 19, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, A.D.; Harris-Hayes, M.; Schootman, M. Epidemiology of Diabetes and Diabetes-Related Complications. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, N.; Mahotra, N.B.; Shrestha, L.; Shrestha, T.M.; Tripathi, P.; Gupta, M.; Gurung, S. Prevalence of hearing impairment in patients with diabetes mellitus at tertiary care center of Nepal. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 8, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xipeng, L.; Ruiyu, L.; Meng, L.; Yanzhuo, Z.; Kaosan, G.; Liping, W. Effects of Diabetes on Hearing and Cochlear Structures. J. Otol. 2013, 8, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, A.-R.; Kim, T.-H.; Shin, S.-A.; Kim, E.-H.; Yu, Y.; Gajbhiye, A.; Kwon, H.-C.; Je, A.R.; Huh, Y.H.; Park, M.J.; et al. Hearing Impairment in a Mouse Model of Diabetes Is Associated with Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Synaptopathy, and Activation of the Intrinsic Apoptosis Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, T.; Yilmaz, N.K.; Rajan, D.; Cureoglu, S.; Monsanto, R.D.C. Middle ear ossicular joint changes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A histopathological study. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 2871–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kui, L.; Dong, C.; Wu, J.; Zhuo, F.; Yan, B.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Xiong, C.; Qiu, P. Causal association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute suppurative otitis media: Insights from a univariate and multivariate Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1407503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.S.; Meganadh, K.R. Prevalence of Otological Disorders in Diabetic Cases with Hearing Loss. J. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 7, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Eavey, R.D.; Wang, M.; Curhan, S.G.; Curhan, G.C. Type 2 diabetes and the risk of incident hearing loss. Diabetologia 2018, 62, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Choi, Y.; Kwon, M.-J.; Moon, I.J.; Deal, J.A.; Lin, F.R.; Guallar, E.; et al. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of hearing loss: A cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 46, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; AlMomani, M.; AlGethami, A.K.; Darandari, J.; Alsalhi, A.; AlNaqeeb, D.; Almogbel, E.; Almasaari, F.H.; Youssef, A.M. Hearing loss among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoza-Shangase, K.; Pillay, D.; Moolla, A. Diabetes and the audiologist: Is there need for concern regarding hearing function in diabetic adults? S. Afr. J. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. 2013, 10, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hlayisi, V.-G.; Petersen, L.; Ramma, L. High prevalence of disabling hearing loss in young to middle-aged adults with diabetes. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2018, 39, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- AlJasser, A.; Uus, K.; Prendergast, G.; Plack, C.J. Subclinical Auditory Neural Deficits in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Ear Hear. 2019, 41, 561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, C.; Casqueiro, J.; Casqueiro, J. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: A review of pathogenesis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Khoza-Shangase, K.; Anastasiou, J. An exploration of recorded otological manifestations in South African children with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 133, 109960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebothoma, B.; Khoza-Shangase, K. Middle ear status—Structure, function and pathology: A scoping review on middle ear status of COVID-19 positive patients. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2022, 69, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sebothoma, B.; Khoza-Shangase, K.; Mol, D.; Masege, D. The sensitivity and specificity of wideband absorbance measure in identifying pathologic middle ears in adults living with HIV. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2021, 68, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebothoma, B.; Maluleke, M. Middle ear pathologies in children living with HIV: A scoping review. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2022, 69, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosthuizen, I.; Frisby, C.; Chadha, S.; Manchaiah, V.; Swanepoel, D.W. Combined hearing and vision screening programs: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1119851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romli, M.; Timmer, B.H.B.; Dawes, P. Hearing care services for adults with hearing loss in Malaysia: A scoping review. Int. J. Audiol. 2023, 63, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pheiffer, C.; Wyk, V.P.V.; Turawa, E.; Levitt, N.; Kengne, A.P.; Bradshaw, D. Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in South Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebola, S.O.; Olamoyegun, M.A.; Sogebi, O.A.; Iwuala, S.O.; Babarinde, J.A.; Oyelakin, A.O. Otologic and audiologic characteristics of type 2 diabetics in a tertiary health institution in Nigeria. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 82, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, J.N.; Chime, E.N. Hearing thresholds in adult Nigerians with diabetes mellitus: A case–control study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2017, 10, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbudi, A.; Rahmadika, N.; Tjahjadi, A.I.; Ruslami, R. Type 2 Diabetes and its Impact on the Immune System. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020, 16, 442–449. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, P.; Rosenkranz, S.; Hu, W.; Gunasekera, H.; Reath, J. The effect and acceptability of tympanometry and pneumatic otoscopy in general practitioner diagnosis and management of childhood ear disease. BMC Fam. Pract. 2024, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-S.; Lee, D.-K.; Lee, C.-K.; Ko, M.H.; Lee, H.-S. Video pneumatic otoscopy for the diagnosis of otitis media with effusion: A quantitative approach. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2008, 266, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melker, R.A. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of pneumatic otoscopy in primary care using the results of tympanometry as a reference standard. PubMed 1993, 43, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, E.; Mattos, M.; Vieira, G.H.A.; Chen, S.; Corrêa, J.D.; Wu, Y.; Albiero, M.L.; Bittinger, K.; Graves, D.T. Diabetes enhances IL-17 expression and alters the oral microbiome to increase its pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Study Domain | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Adult participants, aged 18 years and older | Pediatric population |

| Concept (C) | Middle ear function and pathologies in adults diagnosed with diabetes | Studies focusing on sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and/or central auditory pathologies |

| Context (C) | No restriction | No exclusion |

| Author/s (date) | Publication Title | Publication Focus and Aim | Study Design | Measures Used | Study Participants | Context | Outcome | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adebola et al. (2016) [36] | Otologic and audiologic characteristics of type 2 diabetics in a tertiary health institution in Nigeria. | To describe the pattern of otologic diseases and auditory acuities in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, comparing this with those of non-diabetics and to explore the determinants of these patterns. | Cross-sectional and comparative study | Interviews, digital weight scale, BMI, plasma glucose levels, pneumatic otoscopy, pure tone audiometry. | The study included 97 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and 90 non-diabetic patients. | Nigeria | There were 19.6% diagnosed with otitis media with effusion, 15.5% with perforated tympanic membrane, 14.2% of CHL (lower than the control). | Did not use sensitive measure of middle ear pathologies such as tympanometry. Pneumatic otoscopy is only sensitive for middle ear effusion. |

| Nwosu and Chime (2017) [37] | Hearing thresholds in adult Nigerians with diabetes mellitus: a case–control study. | To determine the prevalence, types and severity of hearing loss and associated factors in a hospital population of adult Nigerians with diabetes mellitus. | Case–control | Blood samples, urine samples, otologic examination including otoscopy, pure tone audiometry. | The study included 224 patients and 192 control participants. The patients comprised 112 males and 112 females (sex ratio = 1:1), whose mean age was 47.6 years (range: 26–80 years), diagnosed with diabetes. | Nigeria | Prevalence of CHL (air–bone gap of greater than 15 dBHL) was 3.1% in people with DM and 0% in control group. | Did not include sensitive measure of middle ear pathologies such as tympanometry. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sebothoma, B.; Khoza-Shangase, K.; Khumalo, G.; Mokwena, B. Exploring Middle Ear Pathologies in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Available Evidence and Research Gaps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040503

Sebothoma B, Khoza-Shangase K, Khumalo G, Mokwena B. Exploring Middle Ear Pathologies in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Available Evidence and Research Gaps. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040503

Chicago/Turabian StyleSebothoma, Ben, Katijah Khoza-Shangase, Gift Khumalo, and Boitumelo Mokwena. 2025. "Exploring Middle Ear Pathologies in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Available Evidence and Research Gaps" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040503

APA StyleSebothoma, B., Khoza-Shangase, K., Khumalo, G., & Mokwena, B. (2025). Exploring Middle Ear Pathologies in Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: A Scoping Review of Available Evidence and Research Gaps. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040503