Dietary Patterns in Relation to Asthma and Wheeze Among Adolescents in a South African Rural Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

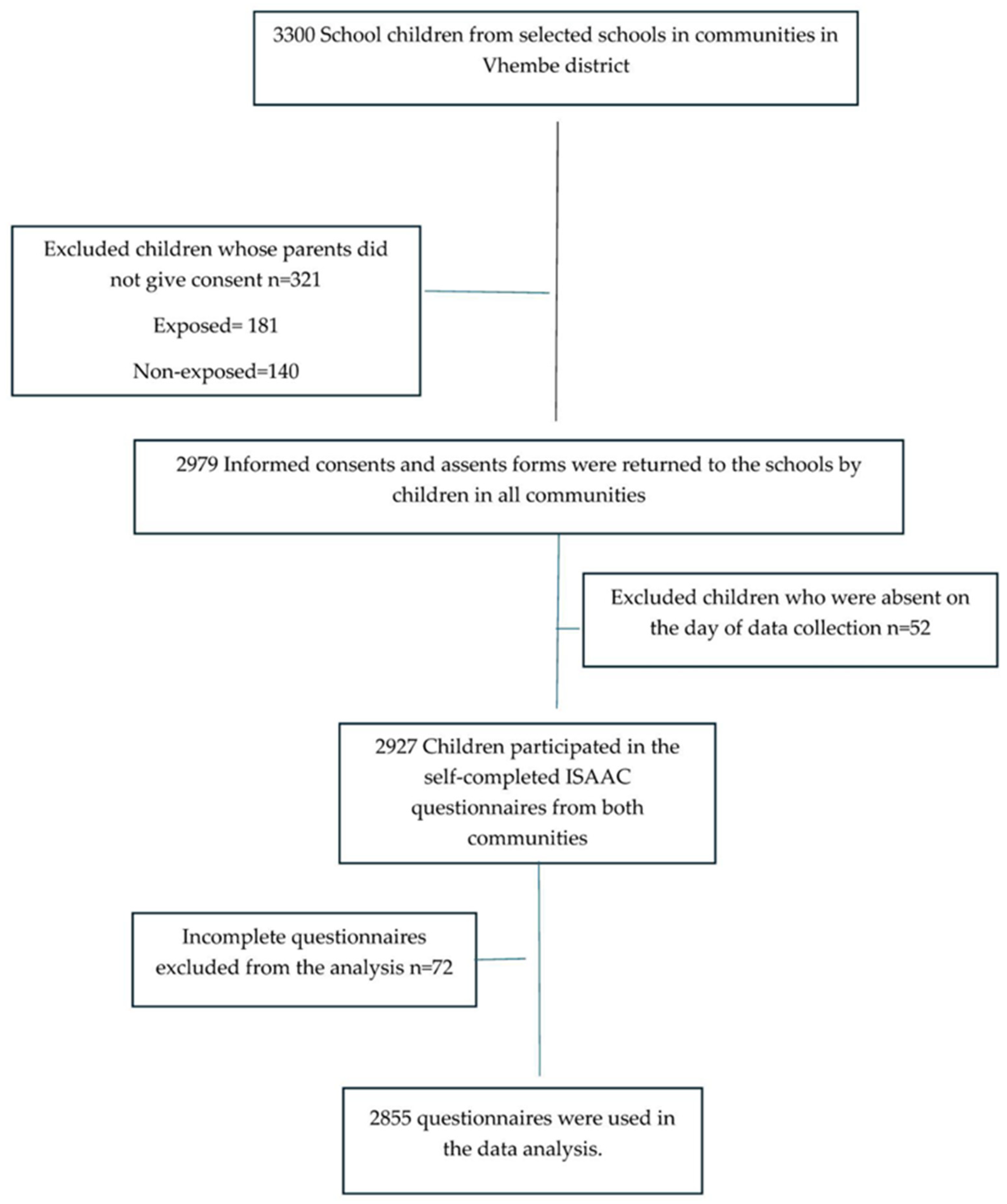

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Health Outcomes

2.5. Assessment of Dietary Patterns

2.6. Confounding Variables

2.7. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Health Outcomes and Frequency of Food Consumption Among Study Participants

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | p | (95% CI) | p | |

| SEAFOOD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.15 (0.93–1.43) | 0.18 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 0.65 |

| Most or all days | 1.79 (0.65–1.24) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.03–2.49) | 0.035 |

| FRUIT | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.64 (0.46–0.89) | 0.009 | 0.75 (0.41–1.36) | 0.34 |

| Most or all days | 0.65 (0.48–0.88) | 0.006 | 0.81 (0.45–1.45) | 0.48 |

| CEREAL | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.93 (0.72–1.21) | 0.62 | 0.74 (0.50–1.07) | 0.11 |

| Most or all days | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 0.003 | 0.67 (0.45–0.99) | 0.050 |

| BREAD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.76 (0.56–1.03) | 0.08 | 0.87 (0.52–1.46) | 0.60 |

| Most or all days | 0.60 (0.45–1.81) | 0.001 | 0.75 (0.45–1.23) | 0.26 |

| PASTA | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 0.26 | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.48 |

| Most or all days | 1.39 (1.06–1.84) | 0.017 | 1.46 (0.98–2.19) | 0.06 |

| NUTS | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.85 (0.65–1.12) | 0.027 | 1.55 (1.11–2.17) | 0.010 |

| Most or all days | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 0.67 | 1.43 (0.94–2.17) | 0.08 |

| FAST FOOD BURGER | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.00 (0.78–1.27) | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.76–1.62) | 0.57 |

| Most or all days | 1.41 (1.06–1.88) | 0.016 | 1.24 (0.78–1.97) | 0.34 |

| FAST FOOD EXCL. BURGER | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.90 (0.70–1.14) | 0.39 | 0.75 (0.51–1.10) | 0.15 |

| Most or all days | 1.32 (1.00–1.74) | 0.049 | 0.88 (0.57–1.36) | 0.56 |

| How many times a week do you engage in vigorous physical activity | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 3.83 (3.08–4.77) | <0.001 | 2.77 (1.99–3.83) | <0.001 |

| Most or all days | 3.15 (2.33–4.26) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.42–3.64) | 0.001 |

| During a normal week of 7 days, how many hours a day (24 h) do you watch television? | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.35 (1.08–1.68) | 0.007 | 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | 0.10 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 1.10 (0.79–1.53) | 0.54 | 1.42 (0.88–2.29) | 0.14 |

| 5 h or more | 0.93 (0.67–1.30) | 0.70 | 0.90 (0.55–1.49) | 0.70 |

| During a normal week of 7 days, how many hours a day (24 h) do you spend on any social games? | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.07 (0.83–1.37) | 0.58 | 0.75 (0.51–1.09) | 0.13 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 1.75 (1.35–2.27) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.55–1.27) | 0.41 |

| 5 h or more | 1.31 (0.97–1.76) | 0.07 | 0.65 (0.41–1.04) | 0.07 |

| Are you twin? | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 3.62 (2.78–4.70) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.16–2.85) | 0.008 |

| How often do trucks pass through the street where you live on weekdays? | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Seldom | 1.46 (1.12–1.90) | 0.005 | 1.16 (0.76–1.77) | 0.46 |

| Frequently through the day | 2.52 (1.94–3.26) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.04–2.55) | 0.033 |

| Almost the whole day | 1.65 (1.25–2.16) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.07–2.44) | 0.022 |

| In the past 12 months how often, on average, have you taken paracetamol? | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| At least once a year | 2.73 (2.19–3.40) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.74–1.53) | 0.70 |

| At least once a month | 2.50 (1.90–3.29) | <0.001 | 1.91 (1.29–2.81) | 0.001 |

| In the past 12 months, have you had a cat in your home? | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 2.22 (0.81–2.71) | <0.001 | 1.22 (0.88–1.69) | 0.21 |

| Do you smoke water pipe? | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 2.62 (2.01–3.42) | <0.001 | 1.54 (0.95–2.49) | 0.07 |

| What fuel is usually used for cooking? | ||||

| Electricity | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gas | 1.93 (1.49–2.51) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.51–1.29) | 0.39 |

| Paraffin | 3.90 (2.61–5.82) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.29–0.77) | 0.003 |

| Open fires | 1.19 (0.94–1.51) | 0.14 | 0.65 (0.36–1.19) | 0.16 |

| What fuel is usually used for heating? | ||||

| Electricity | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gas | 2.09 (1.60–2.72) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.75–1.84) | 0.46 |

| Paraffin | 0.93 (0.70–1.24) | 0.66 | 1.69 (0.84–3.38) | 0.13 |

| Open fires | 0.84 (0.56–1.28) | 0.43 | 1.31 (0.91–1.89) | 0.13 |

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | p | (95% CI) | p | |

| SEAFOOD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.25 (0.94–1.68) | 0.27 | 1.56 (1.01–2.40) | 0.042 |

| Most or all days | 1.61 (1.04–2.50) | 0.030 | 1.22 (0.66–2.23) | 0.51 |

| FRUIT | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.76 (0.94–1.23) | 0.27 | 0.14 (0.50–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Most or all days | 0.62 (0.39–0.98) | 0.041 | 0.12 (0.04–0.33) | <0.001 |

| BUTTER | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.66 (0.48–0.92) | 0.015 | 0.55 (0.35–0.87) | 0.012 |

| Most or all days | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | 0.33 | 0.36 (0.20–0.63) | <0.001 |

| OTHER DAIRY | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.94 (0.66–1.32) | 0.72 | 1.35 (0.83–2.22) | 0.22 |

| Most or all days | 1.51 (1.01–2.25) | 0.040 | 2.35 (1.30–4.25) | 0.005 |

| FAST FOOD BURGER | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.03 (0.75–1.42) | 0.83 | 0.85 (0.51–1.43) | 0.55 |

| Most or all days | 1.54 (1.03–2.31) | 0.034 | 1.17 (0.61–2.27) | 0.62 |

| FAST FOOD EXCL. BURGER | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | 0.46 | 1.41 (0.85–2.36) | 0.17 |

| Most or all days | 1.67 (1.11–2.51) | 0.034 | 1.21 (0.60–2.06) | 0.72 |

| FIZZY DRINKS | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | 0.004 | 0.88 (0.48–1.64) | 0.70 |

| Most or all days | 0.81 (0.54–1.23) | 0.34 | 1.12 (0.60–2.06) | 0.25 |

| How many times a week do you engage in vigorous physical activity? | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 2.72 (2.01–3.69) | <0.001 | 2.83 (1.82–4.40) | <0.001 |

| Three or more times a week | 1.67 (1.13–2.46) | 0.010 | 1.48 (0.84–2.62) | 0.17 |

| During a normal week of 7 days, how many hours a day (24 h) do you watch television? | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.26 (0.93–1.70) | 0.12 | 1.07 (0.67–1.71) | 0.76 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 1.64 (1.01–2.66) | 0.042 | 1.44 (0.71–2.92) | 0.29 |

| 5 h or more | 1.36 (0.87–2.12) | 0.16 | 0.68 (0.35–1.31) | 0.25 |

| During a normal week of 7 days, how many hours a day (24 h) do you spend on any social games? | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.07 (0.77–1.49) | 0.64 | 0.82 (0.49–1.35) | 0.44 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 1.90 (1.29–2.78) | 0.001 | 0.94 (0.50–1.76) | 0.85 |

| 5 h or more | 1.36 (0.82–1.82) | 0.30 | 0.88 (0.48–1.61) | 0.68 |

| Are you a TWIN? | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 1.75 (1.17–2.61) | 0.006 | 0.93 (0.51–1.70) | 0.83 |

| How often do trucks pass through the street where you live on weekdays? | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Seldom | 1.31 (0.92–1.86) | 0.12 | 1.77 (1.03–3.05) | 0.038 |

| Frequently through the day | 2.19 (1.51–3.18) | <0.001 | 2.47 (1.32–4.62) | 0.004 |

| Almost the whole day | 1.28 (0.90–1.83) | 0.16 | 1.43 (0.83–2.48) | 0.19 |

| In the past 12 months, how often, on average, have you taken paracetamol? | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| At least once a year | 1.69 (1.26–2.28) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.66–1.71) | 0.79 |

| At least once a month | 2.29 (1.57–3.62) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.74–2.27) | 0.35 |

| In the past 12 months, have you had a cat in your home? | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| yes | 0.43 (1.69–3.07) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.05–2.63) | 0.029 |

| What fuel is usually used for cooking? | ||||

| Electricity | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gas | 1.27 (0.88–1.83) | 0.18 | 0.93 (0.51–1.72) | 0.84 |

| Paraffin | 2.88 (1.42–5.82) | 0.003 | 1.53 (0.44–5.29) | 0.49 |

| Open fires | 1.71 (1.22–2.40) | 0.002 | 2.60 (1.57–4.32) | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISAAC | International Study of Childhood Asthma and Allergies in Children |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| UNIVEN | University of Venda |

| DHET | Department of Higher Education and training |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| MLR | Multivariate Logistic Regression |

| EIB | Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction |

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| Th-2 | T helper cell type 2 |

| IgE | Immunoglobin E |

| PUFA-6 | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| IRS | Indoor Residual Spraying |

References

- Rodrigues, M.; de Castro Mendes, F.d.C.; Delgado, L.; Padrão, P.; Paciência, I.; Barros, R.; Rufo, J.C.; Silva, D.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Diet and Asthma: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, M.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C. The Effects of a Healthy Diet on Asthma and Wheezing in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Asthma Allergy 2023, 16, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, H.D.; Chang, C.; Teuber, S.S.; Gershwin, M.E. The Clinical Definitions of Asthma. Bronchial Asthma: A Guide for Practical Understanding and Treatment; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Masoli, M.; Fabian, D.; Holt, S.; Beasley, R.; Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Program. The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy 2004, 59, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braman, S.S. The Global Burden of Asthma. Chest 2006, 130, 4S–12S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathogwa-Takalani, F.; Mudau, T.R.; Patrick, S.; Shirinde, J.; Voyi, K. The Prevalence of Childhood Asthma, Respiratory Symptoms and Associated Air Pollution Sources Among Adolescent Learners in Selected Schools in Vhembe District, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudau, R.; Voyi, K.; Shirinde, J. Prevalence of Wheezing and Its Association with Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure among Rural and Urban Preschool Children in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, V.; Rathogwa-Takalani, F.; Voyi, K. The Frequency of Fast Food Consumption in Relation to Wheeze and Asthma Among Adolescents in Gauteng and North West Provinces, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustad, N.; Bønnelykke, K.; Chawes, B. Dietary prevention strategies for childhood asthma. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 34, e13984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, I.; Stewart, A.W.; Hancox, R.J.; Beasley, R.; Murphy, R.; Mitchell, E.A.; the ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Fast-food consumption and body mass index in children and adolescents: An international cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozańska, B.; Sikorska-Szaflik, H. Diet Modifications in Primary Prevention of Asthma. Where Do We Stand? Nutrients 2021, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Mutius, E.; Smits, H.H. Primary prevention of asthma: From risk and protective factors to targeted strategies for prevention. Lancet 2020, 396, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunjani, N.; Walsh, L.J.; Venter, C.; Power, M.; MacSharry, J.; Murphy, D.M.; O’Mahony, L. Environmental influences on childhood asthma—The effect of diet and microbiome on asthma. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, L.; Williams, E.J.; Scott, H.A.; Berthon, B.S.; Jensen, M.; Wood, L.G. Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Nutrients 2017, 9, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaeb, D.; Hallit, S.; Sacre, H.; Malaeb, B.; Hallit, R.; Salameh, P. Diet and asthma in Lebanese school children: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 688–697. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzi, L.; Apostolaki, G.; Bibakis, I.; Skypala, I.; Bibaki-Liakou, V.; Tzanakis, N.; Kogevinas, M.; Cullinan, P. Protective effect of fruits, vegetables and the Mediterranean diet on asthma and allergies among children in Crete. Thorax 2007, 62, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogenkamp, A.; Ehlers, A.; Garssen, J.; Willemsen, L.E.M. Allergy Modulation by N-3 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Fat Soluble Nutrients of the Mediterranean Diet. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwood, P.; Asher, M.I.; Beasley, R.; Clayton, T.O.; Stewart, A.W.; ISAAC Steering Committee. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): Phase three rationale and methods [research methods]. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood, P. ISAAC III Manual; ISAAC International Data Centre: Auckland, New Zealand, 2000; Available online: https://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/phases/phasethree/phasethreemanual.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Lory, G.L. STATA: Software for Statistics and Data Software. In The Encyclopedia of Research Methods in Criminology and Criminal Justice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 875–879. [Google Scholar]

- Mphahlele, R.; Lesosky, M.; Masekela, R. Prevalence, severity and risk factors for asthma in school-going adolescents in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, J.; Bouwman, H.; Barnhoorn, I.; Bornman, M. DDT contamination from indoor residual spraying for malaria control. Sci. Total. Environ. 2010, 408, 2745–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osunkentan, A.; Evans, D. Chronic adverse effects of long-term exposure of children to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) through indoor residual spraying: A systematic review. Rural. Remote Health 2015, 15, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwarith, J.; Kahleova, H.; Crosby, L.; Brooks, A.; Brandon, L.; Levin, S.M.; Barnard, N.D. The role of nutrition in asthma prevention and treatment. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varraso, R.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Diet and asthma: Need to account for asthma type and level of prevention. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2016, 10, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; E Ellwood, P.; Asher, M.I. Diet and asthma: Looking back, moving forward. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereux, S.; Hochfeld, T.; Karriem, A.; Mensah, C.; Morahanye, M.; Msimango, T.; Mukubonda, A.; Naicker, S.; Nkomo, G.; Sanders, D.; et al. School Feeding in South Africa: What We Know, What We Don’t Know; DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security: Bellville, South Africa, 2018; Available online: https://foodsecurity.ac.za (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Nagel, G.; Weinmayr, G.; Kleiner, A.; Garcia-Marcos, L.; Strachan, D. Effect of diet on Asthma and Allergic sensitization in Phase Two International Study on Allergies and Asthma in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. Das Gesundheitswesen 2010, 65, 516–522. [Google Scholar]

- Berthon, B.S.; McLoughlin, R.F.; Jensen, M.E.; Hosseini, B.; Williams, E.J.; Baines, K.J.; Taylor, S.L.; Rogers, G.B.; Ivey, K.L.; Morten, M.; et al. The effects of increasing fruit and vegetable intake in children with asthma: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-K.; Ju, S.-Y. Association of fruit and vegetable consumption with asthma: Based on 2013–2017 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Nutr. Health 2020, 53, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.d.C.; Paciência, I.; Rufo, J.C.; Farraia, M.; Silva, D.; Padrão, P.; Delgado, L.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Higher diversity of vegetable consumption is associated with less airway inflammation and prevalence of asthma in school-aged children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 32, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, M.F.; Lopata, A.L. Fish allergy: In review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 46, 258–271. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, S.Y.; Schwartzstein, R. Asthma: Pathophysiology and diagnosis. In Asthma, Health and Society: A Public Health Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Prester, L. Seafood Allergy, Toxicity, and Intolerance: A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevhertas, L.; Ogulur, I.; Maurer, D.J.; Burla, D.; Ding, M.; Jansen, K.; Koch, J.; Liu, C.; Ma, S.; Mitamura, Y.; et al. Advances and recent developments in asthma in 2020. Allergy 2020, 75, 3124–3146. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.; Humbert, M.; Buhl, R.; Cruz, A.A.; Inoue, H.; Korom, S.; Hanania, N.A.; Nair, P. Revisiting T ype 2-high and T ype 2-low airway inflammation in asthma: Current knowledge and therapeutic implications. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2017, 47, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nafstad, P.; Nystad, W.; Magnus, P.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis at 4 Years of Age in Relation to Fish Consumption in Infancy. J. Asthma 2003, 40, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C.; Kremmyda, L.-S.; Vlachava, M.; Noakes, P.S.; Miles, E.A. Is there a role for fatty acids in early life programming of the immune system? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopata, A.L.; Jeebhay, M.F. Airborne Seafood Allergens as a Cause of Occupational Allergy and Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013, 13, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeebhay, M.F.; Lopata, A.L. Occupational allergies in seafood-processing workers. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 66, 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Emrani, A.S.; Sasanfar, B.; Nafei, Z.; Behniafard, N.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. Association between Butter, Margarine, and Olive Oil Intake and Asthma Symptoms among School Children: Result from a Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 2884630. [Google Scholar]

- Whyand, T.; Hurst, J.R.; Beckles, M.; Caplin, M.E. Pollution and respiratory disease: Can diet or supplements help? A review. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzoletti, L.; Zanolin, M.E.; Spelta, F.; Bono, R.; Chamitava, L.; Cerveri, I.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Grosso, A.; Mattioli, V.; Pirina, P.; et al. Dietary fats, olive oil and respiratory diseases in Italian adults: A population-based study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 799–807. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, F.; Tesse, R.; Fucilli, C.; Loffredo, M.S.; Iacoviello, G.; Chinellato, I.; Armenio, L. Correlation between exhaled nitric oxide and dietary consumption of fats and antioxidants in children with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 1268–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ghosh, B. Genetics of asthma: A molecular biologist perspective. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2009, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R.W.; Nwaru, B.I.; Roduit, C.; Untersmayr, E.; Adel-Patient, K.; Agache, I.; Agostoni, C.; Akdis, C.A.; Bischoff, S.C.; et al. EAACI position paper: Influence of dietary fatty acids on asthma, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2019, 74, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogulska, A.; Dynowski, J.; Jędrzejczyk, M.; Sardecka, I.; Małachowska, B.; Wąsowska-Królikowska, K. The impact of food allergens on airway responsiveness in schoolchildren with asthma: A DBPCFC study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2016, 51, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, C.R.; Stewart, A.W.; Hancox, R.J.; Murphy, R.; Braithwaite, I.; Beasley, R.; Mitchell, E.A.; The ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Association between Frequency of Consumption of Fruit, Vegetables, Nuts and Pulses and BMI: Analyses of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Nutrients 2018, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffin, J.M.; Sheehan, W.J.; Morrill, J.; Cinar, M.; Borras Coughlin, I.M.; Sawicki, G.S.; Twarog, F.J.; Young, M.C.; Schneider, L.C.; Phipatanakul, W. Tree nut allergy, egg allergy, and asthma in children. Clin. Pediatr. 2011, 50, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Borres, M.P.; Sato, S.; Ebisawa, M. Recent advances in diagnosing and managing nut allergies with focus on hazelnuts, walnuts, and cashew nuts. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, G.; Apprich, S.; Waser, M.; Kneifel, W.; Genuneit, J.; Büchele, G.; Weber, J.; Sozanska, B.; Danielewicz, H.; Horak, E.; et al. The protective effect of farm milk consumption on childhood asthma and atopy: The GABRIELA study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 766–773. [Google Scholar]

- Sozańska, B.; Pearce, N.; Dudek, K.; Cullinan, P. Consumption of unpasteurized milk and its effects on atopy and asthma in children and adult inhabitants in rural Poland. Allergy 2013, 68, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R.K.; Walters, E.H.; Raven, J.M.; Wolfe, R.; Ireland, P.D.; Thien, F.C.; Abramson, M.J. Food and nutrient intakes and asthma risk in young adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.Y.; Forno, E.; Brehm, J.M.; Acosta-Pérez, E.; Alvarez, M.; Colón-Semidey, A.; Rivera-Soto, W.; Campos, H.; Litonjua, A.A.; Alcorn, J.F.; et al. Diet, interleukin-17, and childhood asthma in Puerto Ricans. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 115, 288–293. [Google Scholar]

- Agache, I.; Eguiluz-Gracia, I.; Cojanu, C.; Laculiceanu, A.; del Giacco, S.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Kosowska, A.; Akdis, C.A.; Jutel, M. Advances and highlights in asthma in 2021. Allergy 2021, 76, 3390–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kamp, M.R.; Thio, B.J.; Tabak, M.; Hermens, H.J.; Driessen, J.M.; van der Palen, J.A. Does exercise-induced bronchoconstriction affect physical activity patterns in asthmatic children? J Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 24, 577–588. [Google Scholar]

- Turek, E.M.; Cox, M.J.; Hunter, M.; Hui, J.; James, P.; Willis-Owen, S.A.; Cuthbertson, L.; James, A.; Musk, A.; Moffatt, M.F.; et al. Airway microbial communities, smoking and asthma in a general population sample. EBioMedicine 2021, 71, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiotiu, A.; Ioan, I.; Wirth, N.; Romero-Fernandez, R.; González-Barcala, F.-J. The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.-Y.; Rosser, F.; Forno, E.; Celedón, J.C. Electronic vapor products, marijuana use, smoking, and asthma in US adolescents. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1025–1028.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Dharmage, S.C.; Lodge, C.J. The relationship of early-life household air pollution with childhood asthma and lung function. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Brunekreef, B.; Gehring, U. Meta-analysis of the effects of indoor nitrogen dioxide and gas cooking on asthma and wheeze in children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenwald, T.; Seals, B.A.; Knibbs, L.D.; Hosgood, H.D. Population Attributable Fraction of Gas Stoves and Childhood Asthma in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthma Australia. Homes, Health and Asthma in Australia; Asthma Australia: Chatswood, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, N.R.; Doty, K.J.; Guidinger, C.; Folger, A.; Luther, G.M.; Giuliani, N.R. Social desirability bias is related to children’s energy intake in a laboratory test meal paradigm. Appetite 2024, 195, 107235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma Ever | ||

| Yes | 533 | 18.67 (18.91) |

| No | 2286 | 80.07 (81.09) |

| Wheeze Ever | ||

| Yes | 1076 | 37.69 (38.06) |

| No | 1751 | 61.33 (61.94) |

| Wheeze in the Past 12 Months | ||

| Yes | 705 | 24.69 (67.40) |

| No | 341 | 11.94 (32.50) |

| Bread | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 357 | 12.50 (13.52) |

| Once or twice per week | 861 | 30.16 (32.60) |

| Most or all days | 1423 | 49.84 (53.88) |

| Meat | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 320 | 11.21 (11.89) |

| Once or twice per week | 1401 | 49.07 (52.04) |

| Most or all days | 971 | 34.01 (36.07) |

| Seafood | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 1185 | 41.51 (45.19) |

| Once or twice per week | 1129 | 39.54 (43.06) |

| Most or all days | 308 | 10.79 (11.75) |

| Raw vegetables | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 931 | 32.61 (36.27) |

| Once or twice per week | 1089 | 38.14 (42.42) |

| Most or all days | 547 | 19.16 (21.31) |

| Butter | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 805 | 28.20 (31.31) |

| Once or twice per week | 1178 | 41.26 (45.87) |

| Most or all days | 588 | 20.49 (22.78) |

| Olive oil | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 980 | 34.33 (39.72) |

| Once or twice per week | 918 | 32.15 (37.21) |

| Most or all days | 569 | 19.93 (23.06) |

| Fast food burgers | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 767 | 26.87 (29.82) |

| Once or twice per week | 1304 | 41.44 (50.70) |

| Most or all days | 501 | 18.04 (19.48) |

| Fast food excl. burgers | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 786 | 27.53 (31.64) |

| Once or twice per week | 1183 | 41.44 (47.62) |

| Most or all days | 515 | 18.04 (20.73) |

| Fizzy drinks | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 492 | 17.23 (19.00) |

| Once or twice per week | 1139 | 39.89 (43.99) |

| Most or all days | 958 | 33.56 (37.00) |

| Other dairy | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 648 | 22.70 (25.76) |

| Once or twice per week | 1238 | 43.36 (49.21) |

| Most or all days | 630 | 22.07 (25.04) |

| Fruit | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 270 | 9.46 (9.98) |

| Once or twice per week | 922 | 32.29 (34.07) |

| Most or all days | 1514 | 53.03 (55.95) |

| Potatoes | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 558 | 19.54 (21.60) |

| Once or twice per week | 1357 | 47.53 (52.54) |

| Most or all days | 668 | 23.40 (25.86) |

| Nuts | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 901 | 31.56 (35.29) |

| Once or twice per week | 1180 | 41.33 (46.22) |

| Most or all days | 472 | 16.53 (18.49) |

| Cereal | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 559 | 19.58 (22.35) |

| Once or twice per week | 947 | 33.17 (37.86) |

| Most or all days | 995 | 34.85 (39.78) |

| Pasta | ||

| Never or only occasionally | 859 | 30.09 (33.83) |

| Once or twice per week | 1196 | 41.89 (47.11) |

| Most or all days | 484 | 16.95 (19.06) |

| Variable | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | p | (95% CI) | p | |

| CEREAL | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 0.24 | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | 0.17 |

| Most or all days | 0.80 (0.64–0.99) | 0.042 | 0.75 (0.54–1.05) | 0.09 |

| BREAD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | 0.026 | 0.74 (0.47–1.15) | 0.19 |

| Most or all days | 0.79 (0.63–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.95 (0.61–1.47) | 0.84 |

| PASTA | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.05 (0.88–1.27) | 0.56 | 1.18 (0.90–1.56) | 0.21 |

| Most or all days | 1.30 (1.03–1.64) | 0.022 | 0.91 (0.63–1.30) | 0.61 |

| RICE | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.65 (0.52–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.67–1.41) | 0.89 |

| Most or all days | 0.98 (0.77–1.26) | 0.83 | 1.02 (0.67–1.54) | 0.90 |

| OLIVE OIL | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | 0.50 | 1.17 (0.89–1.53) | 0.23 |

| Most or all days | 1.40 (1.13–1.73) | 0.002 | 1.48 (1.09–2.00) | 0.027 |

| OTHER DAIRY | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 0.59 | 1.17 (0.87–1.59) | 0.28 |

| Most or all days | 1.28 (1.02–1.61) | 0.028 | 1.21 (0.85–1.73) | 0.27 |

| NUTS | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.21 (1.00–1.45) | 0.046 | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 0.32 |

| Most or all days | 1.88 (1.50–2.37) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.33–2.66) | <0.001 |

| FAST FOOD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | 0.88 | 0.97 (0.73–1.29) | 0.84 |

| Most or all days | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) | 0.037 | 0.91 (0.63–1.31) | 0.62 |

| MEAT | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 0.050 | 0.90 (0.58–1.41) | 0.66 |

| Most or all days | 1.01 (0.77–1.30) | 0.95 | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 0.59 |

| SEAFOOD | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 0.93 | 0.76 (0.59–0.96) | 0.027 |

| Most or all days | 1.33 (1.03–1.72) | 0.028 | 0.88 (0.59–1.30) | 0.52 |

| FRUIT | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 0.66 (0.50–0.87) | 0.004 | 0.55 (0.32–0.94) | 0.031 |

| Most or all days | 0.78 (0.59–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.59 (0.35–1.01) | 0.06 |

| VEGERAW | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 1.17 (0.97–1.40) | 0.09 | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) | 0.29 |

| Most or all days | 1.32 (1.06–1.64) | 0.013 | 1.26 (0.90–1.74) | 0.16 |

| Fuel used for cooking in the house | ||||

| Electricity | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gas | 1.44 (1.15–1.81) | 0.001 | 0.67 (0.47–0.96) | 0.033 |

| Paraffin | 2.00 (1.36–2.93) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.35–1.27) | 0.22 |

| Open fires (wood, coal) | 1.03 (0.85–1.24) | 0.75 | 0.84 (0.63–1.10) | 0.21 |

| Frequency of trucks passing in the street | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| Seldom (not often) | 1.22 (0.99–1.50) | 0.051 | 0.71 (0.51–0.99) | 0.046 |

| Frequently through the day | 1.90 (1.53–2.37) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.65–1.35) | 0.74 |

| Almost the whole day | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.63–1.22) | 0.44 |

| Smoke water pipe | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 3.00(2.33–3.86) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.10–2.63) | 0.016 |

| Have a cat at home | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.84 (1.55–2.18) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.79–1.36) | 0.77 |

| Use paracetamol | ||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||

| At least once a year | 2.63(2.18–3.16) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.30–2.30) | <0.001 |

| At least once a month | 2.00 (1.58–2.54) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.32–2.57) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Never or only occasionally | 1 | 1 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 4.31 (3.57–5.20) | <0.001 | 3.41 (2.62–4.45) | <0.001 |

| Most or all days | 4.12 (3.17–5.37) | <0.001 | 3.11 (2.07–4.65) | <0.001 |

| Games social | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.17 (0.97–1.43) | 0.09 | 1.18 (0.87–1.59) | 0.27 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 1.43 (1.15–1.78) | 0.001 | 1.09 (0.76–1.54) | 0.62 |

| 5 h or more | 1.31 (1.03–1.66) | 0.024 | 1.33 (0.92–1.92) | 0.12 |

| Watching Television | ||||

| Less than 1 h | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 h but less than 3 h | 1.21 (1.01–1.45) | 0.032 | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 0.22 |

| 3 h but less than 5 h | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) | 0.45 | 1.16 (0.78–1.72) | 0.44 |

| 5 h or more | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) | 0.96 | 1.04(0.71–1.52) | 0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rathogwa-Takalani, F.; Mudau, T.R.; Patrick, S.M.; Shirinde, J.; Voyi, K. Dietary Patterns in Relation to Asthma and Wheeze Among Adolescents in a South African Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040502

Rathogwa-Takalani F, Mudau TR, Patrick SM, Shirinde J, Voyi K. Dietary Patterns in Relation to Asthma and Wheeze Among Adolescents in a South African Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040502

Chicago/Turabian StyleRathogwa-Takalani, Funzani, Thabelo Rodney Mudau, Sean Mark Patrick, Joyce Shirinde, and Kuku Voyi. 2025. "Dietary Patterns in Relation to Asthma and Wheeze Among Adolescents in a South African Rural Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040502

APA StyleRathogwa-Takalani, F., Mudau, T. R., Patrick, S. M., Shirinde, J., & Voyi, K. (2025). Dietary Patterns in Relation to Asthma and Wheeze Among Adolescents in a South African Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040502