Assessment of Psychosocial Risk and Resource Factors Perceived by Military and Civilian Personnel at an Armed Forces Medical Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the French Army, Our Research Field

1.2. Psychosocial Risks in the Army

PSR and Health-Related Resource Factors Identified Among Healthcare Professionals in a Civil Practice Context

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

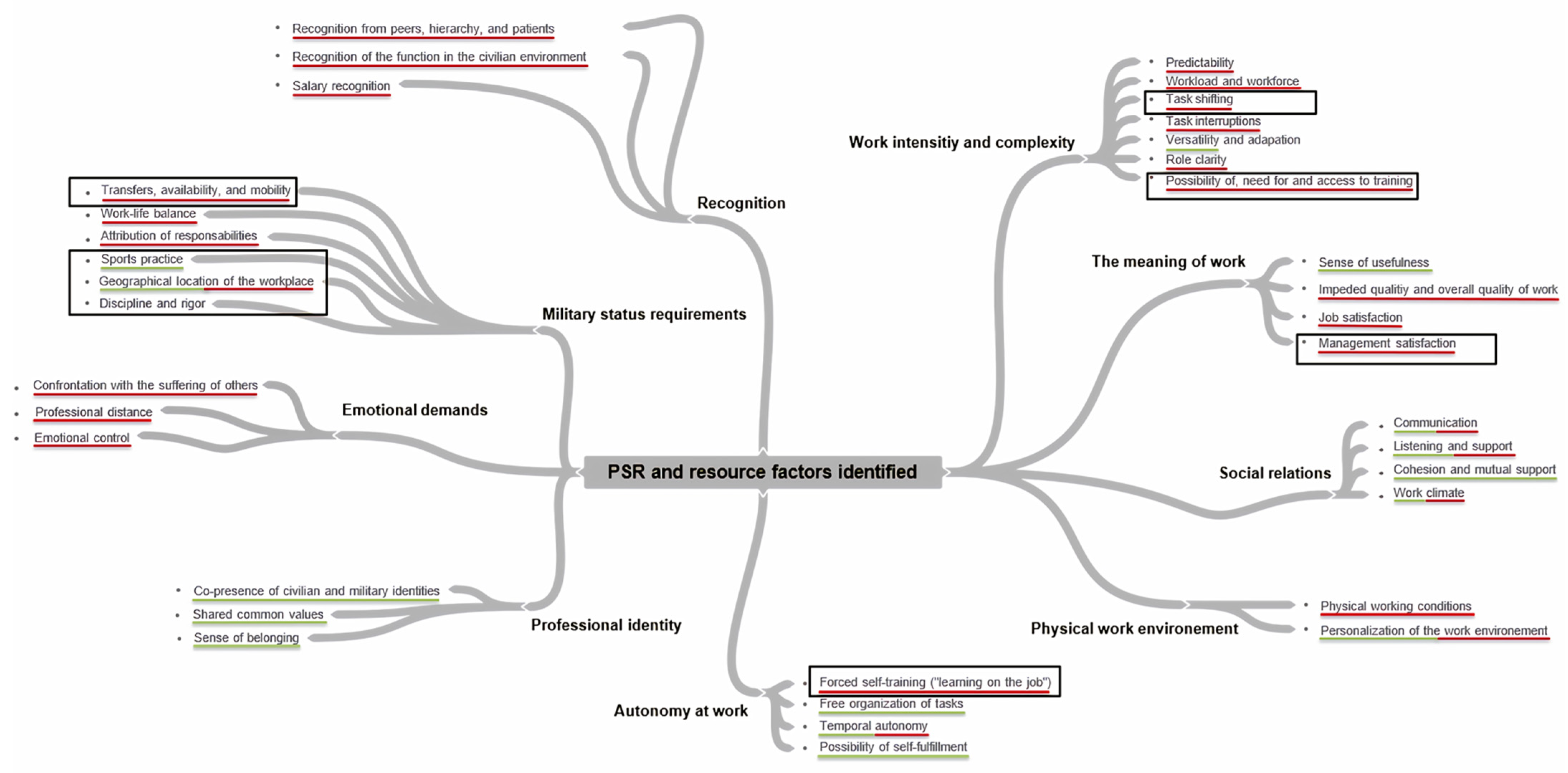

3. Results

3.1. Factors and Sub-Factors Perceived as Psychosocial Risks

3.1.1. Recognition

3.1.2. Emotional Demands

3.2. Factors and Sub-Factors Perceived as a Resource

Professional Identity

3.3. Factors and Sub-Factors Perceived as Both Risks and Resources

3.3.1. Work Intensity and Complexity

3.3.2. Military Status Requirements

3.3.3. Social Relations at Work

3.3.4. The Meaning of Work

3.3.5. Autonomy at Work

3.3.6. Physical Work Environment

3.4. Another Theme Identified: Career Transitions

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths, Limitations and Research Perspectives

4.3. Practical Implications/Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews Presenting, for Each Theme, the Associated Question(s)

| Themes | Questions |

| Function and responsibilities | - Could you describe your function and responsibilities within the medical unit/veterinary group? |

| Variation in activity and perceived workload | - Are there peaks and troughs in your activity, and if so, when do they occur? |

| Perceived professional demands | - What demands can you identify in your work? |

| Perceived facilitators and barriers to activity | - What do you appreciate about your work? - What could be improved? - What is your experience with using the Axone software in your work? |

| Perceived risks | - What risks associated with your activity might you be exposed to? |

| Perceived effects of work on health | - In your opinion, what impact could your work have on your health? |

Appendix B. Table Presenting the Categorization of Identified Themes and Sub-Themes

| Risk Factors | Resource Factors | Uncategorized |

| Emotional demands Confrontation with the suffering of others Professional distance Emotional control | ||

| Military status requirements Transfers, availability, and mobility Geographical location of the workplace Work–life balance Attribution of responsibilities Recognition Recognition from peers, hierarchy, and patients Recognition of the function in the civilian environment Salary recognition Work intensity and complexity Predictability Workload Task shifting Role clarity Task interruptions Possibility of, need for and access to training The meaning of work Job satisfaction Impeded quality and overall quality of work Management satisfaction Social relations at work Communication Listening and support Work climate Physical work environment Physical working conditions Personalization of the work environment Autonomy at work Forced self-training Temporal autonomy | Military status requirements Sports practice Geographical location of the workplace Work intensity and complexity Versatility The meaning of work Feeling of usefulness Social relations at work Communication Listening and support Cohesion and mutual support Work climate Physical work environment Personalization of the work environment Autonomy at work Free organization of tasks Temporal autonomy Possibility of self-fulfillment Professional identity Co-presence of civilian and military identities Shared common values Sense of belonging to the organization | Military status requirements Discipline and rigor Work intensity and complexity Adaptation requirement |

References

- Letonturier, É. Recognition, institution, and military identities. L’Année Sociol. 2011, 61, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godart, P. The military health service: History, stakes, and challenges. Inflexions 2012, 20, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valléry, G.; Leduc, S. Les Risques Psychosociaux (Psychosocial Risks); Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gollac, M.; Bodier, M. Measuring Psychosocial Risk Factors at Work to Control Them. Report from the Expert Committee on the Statistical Monitoring of Psychosocial Risks at Work. 2011. Available online: http://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_SRPST_definitif_rectifie_11_05_10.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Eurofound; EU-OSHA. Psychosocial Risks in Europe: Prevalence and Strategies for Prevention; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Report%20co-branded%20EUROFOUND%20and%20EU-OSHA.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Clot, Y. Le Travail à Cœur. Pour en Finir avec les Risques Psychosociaux (Work at Heart: To Put an End to Psychosocial Risks); La Découverte: Paris, France, 2010; 190p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryon-Portet, C. Work-related stress and suicides within the military institution. Travailler 2011, 26, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflanz, S.; Ogle, A.D. Job Stress, Depression, Work Performance, and Perceptions of Supervisors in Military Personnel. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhuin, O.; Delacour, B.; Jakubowski, S. The impact of professional constraints on engagement in the French Navy. Rev. Défense Natl. 2017, 803, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, R.; Janowitz, M. The professional soldier: A social and political portrait. Rev. Fr. Sci. Polit. 1962, 3, 736–738. [Google Scholar]

- Laberon, S.; Barou, D.; Ripon, A. Psychosocial risks within the military institution: The mediating effect of perceived management style. Le Trav. Hum. 2016, 79, 363–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryon-Portet, C. The rise of internal communication in the armed forces and its limitations: From command to management? Commun. Organ. 2008, 34, 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, S. Military organization in transition: A rationalization of the command system? In Sociology of the Military Environment: The Consequences of Professionalization on the Armed Forces and Military Identity; Gresle, F., Ed.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, F. Karasek’s model. In Psychosocial Risks and Quality of Work Life; Chapelle, F., Ed.; Dunod: Malakoff, France, 2018; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benisti, G.; Baron-Epel, O. Applying the socioecological model to map factors associated with military physical activity adherence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, J.P.; Groeller, H.; Drain, J.R.; Kyröläinen, H.; Pihlainen, K.; Ojanen, T.; Connaboy, C.; Santtila, M.; Agostinelli, P.J.; Nindl, B. Physical training considerations for optimizing performance in essential military tasks. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 22, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lia, M. L’engagement militaire, bien plus que l’exercice d’une profession (Military commitment: Much more than just a profession). J. Psychol. 2019, 372, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ebatetou, E.; Bakala, J.K.; Atipo-Galloye, P.; Renaud, P.; Menga, K.; Kokolo, J.G.; Moukassa, D. Assessment of Psychosocial Risk Factors among Healthcare Professionals in Pointe-Noire (Congo). Health Sci. Dis. 2020, 21, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hegg-Deloye, S.; Brassard, P.; Prairie, J.; Larouche, D.; Jauvin, N.; Tremblay, A.; Corbeil, P. Portrait global de l’exposition aux contraintes psychosociales au travail des paramédics québécois (Overview of exposure to psychosocial constraints at work among Quebec paramedics). Perspect. Interdiscip. Sur Trav. Santé 2014, 16–3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, C.; Wang, S.; Hou, T. A Study of Job Stress, Stress Coping Strategies, and Job Satisfaction for Nurses Working in Middle-Level Hospital Operating Rooms. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 17, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mar Molero Jurado, M.; Del Carmen Pérez Fuentes, M.; Linares, J.J.G.; Del Mar Simón Márquez, M.; Martínez, Á.M. Burnout Risk and Protection Factors in Certified Nursing Aides. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiard, V.; Telliez, F.; Pamart, F.; Libert, J.P. Health, Occupational Stress, and Psychosocial Risk Factors in Night Shift Psychiatric Nurses: The Influence of an Unscheduled Night-Time Nap. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, J.E.; Roland-Lévy, C.; Zaghouani, I.; Deschamps, F. Contribution of categorizing psychosocial risks to predicting stress and burnout (or work-related distress) among caregivers. Psychol. Trav. Organ. 2017, 23, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, P.; Gkiouleka, A. A Scoping Review of Psychosocial Risks to Health Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoorthy, M.S.; Pratapa, S.K.; Mahant, S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Baylina, P.; Fernandes, R.; Ramalho, S.; Arezes, P. Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health in Pandemic Times: The Predict Role of Psychosocial Risks. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampin, R.; Rampin, V. Taguette: Open-source qualitative data analysis. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupret, É.; Bocéréan, C.; Teherani, M.; Feltrin, M. Le COPSOQ: Un nouveau questionnaire français d’évaluation des risques psychosociaux (A new French questionnaire for assessing psychosocial risks). Santé Publique 2012, 24, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INRS; Université Lorraine. SATIN. Well-Being, Occupational Health, Psychosocial Risks. 2016. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/questsatin/home (accessed on 20 March 2023).

| Status | N | Military Occupational Specialty | N | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civilians | 9 | Administrative secretaries | 9 | No rank |

| Active-duty and reserve military personnel | 47 | Medical auxiliaries | 13 | Enlisted personnel |

| Administrative secretaries | 2 | Non-commissioned officers | ||

| Nurses and nurses in charge of medical units | 18 | Non-commissioned officers | ||

| Veterinarians | 2 | Officers | ||

| Psychologist | 1 | Officers | ||

| Doctors and doctors in charge of medical units | 11 | Officers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouché-Bencivinni, A.; Kratzien, V.; Ballester, B.; Boua, M.; Jeoffrion, C. Assessment of Psychosocial Risk and Resource Factors Perceived by Military and Civilian Personnel at an Armed Forces Medical Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040494

Bouché-Bencivinni A, Kratzien V, Ballester B, Boua M, Jeoffrion C. Assessment of Psychosocial Risk and Resource Factors Perceived by Military and Civilian Personnel at an Armed Forces Medical Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040494

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouché-Bencivinni, Alicia, Vanessa Kratzien, Bruno Ballester, Mohamed Boua, and Christine Jeoffrion. 2025. "Assessment of Psychosocial Risk and Resource Factors Perceived by Military and Civilian Personnel at an Armed Forces Medical Center" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040494

APA StyleBouché-Bencivinni, A., Kratzien, V., Ballester, B., Boua, M., & Jeoffrion, C. (2025). Assessment of Psychosocial Risk and Resource Factors Perceived by Military and Civilian Personnel at an Armed Forces Medical Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040494