The Longitudinal Association Between Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment: A Random Intercept Latent Transition Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Attachment and Its Predictors

1.1.1. Stress

1.1.2. School Connectedness

1.1.3. Family Attachment

1.1.4. Social Goals

1.2. Habitual Smartphone

1.3. Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

2.2.2. Peer Attachment

2.2.3. Habitual Smartphone Use

2.2.4. Stress

2.2.5. Family Attachment

2.2.6. School Connectedness

2.2.7. Social Goals

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Correlation Analysis

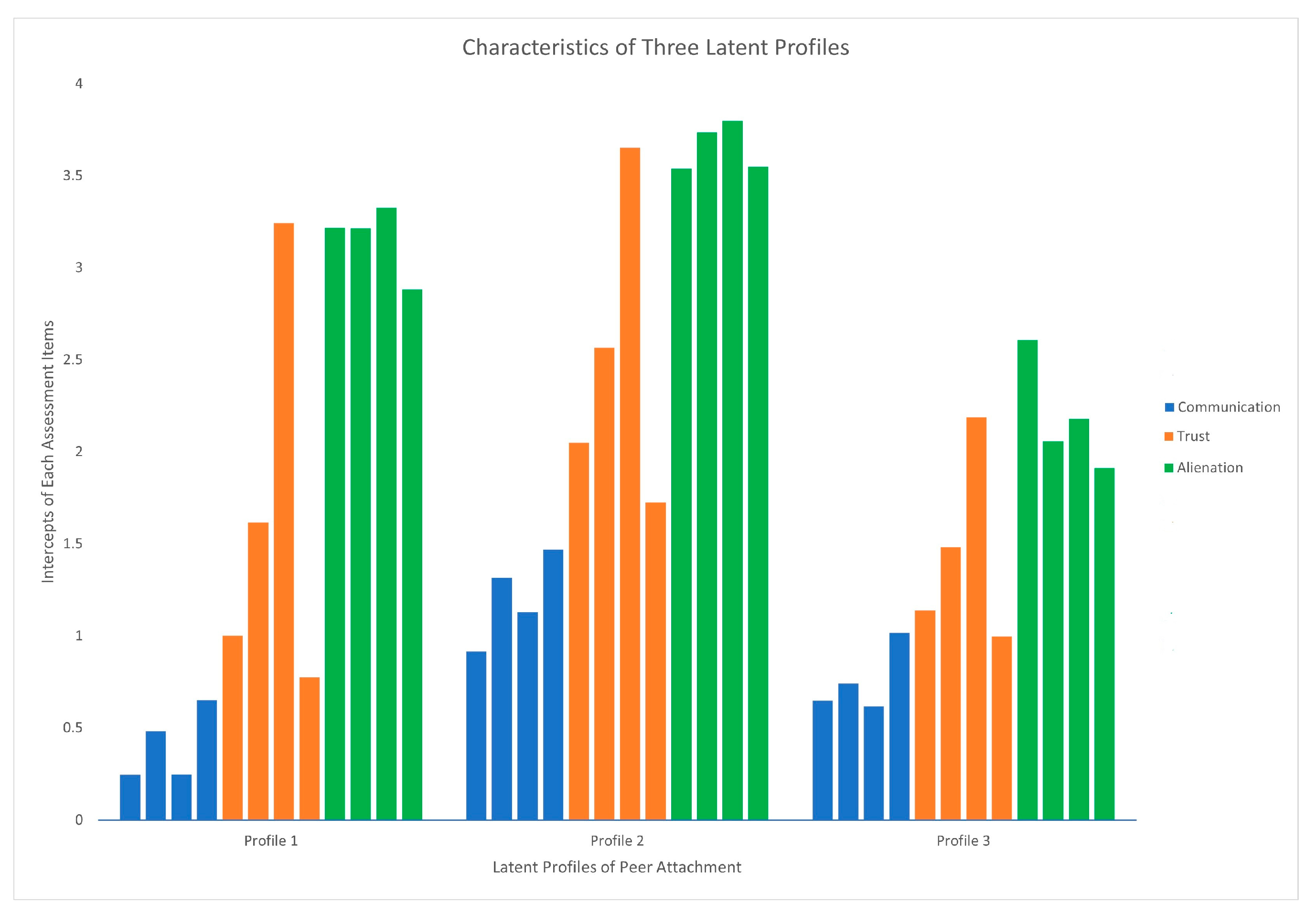

3.3. Profile Enumeration

3.4. RI-LTA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. Teens and Internet, Device Access Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/teens-and-internet-device-access-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Canadian Government EBook Collection; Public Health Agency of Canada. Social Media Use, Connections and Relationships in Canadian Adolescents: Findings from the 2018 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study; Public Health Agency of Canada, Agence de santé publique du Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shapka, J.D. Adolescent technology engagement: It is more complicated than a lack of self-control. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 1, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkin, S.; Bardakci, S.; Ilhan, T. An Investigation of the Associations between the Quality of Social Relationships and Smartphone Addiction in High School Students. Addicta Turk. J. Addict. 2020, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mora, C.; Carlo, G.; Roos, J.; Maiya, S.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, J. Perceived Attachment and Problematic Smartphone Use in Young People: Mediating Effects of Self-Regulation and Prosociality. Psicothema 2021, 33, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Guo, Z.; Hong, D.; Jiang, S. Peer relationship and adolescents’ smartphone addiction: The mediating role of alienation and the moderating role of sex. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 22976–22988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulasvirta, A.; Rattenbury, T.; Ma, L.; Raita, E. Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, M.Q.H.; Chiang, J.; Chua, T.J.X.; Wang, S.; Tan, N.C. The relationship between smartphone addiction and sleep among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarinia, H.R.; Torkamani, M.H.; Farmani, O.; Biglarian, A.; Gabel, C.P. Smartphone addiction in children: Patterns of use and musculoskeletal discomfort during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Exploring the impact of smartphone addiction on mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of resilience and parental attachment. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 367, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.; Bolle, C.L.; Hegner, S.M.; Kommers, P.A. Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behavior The role of smartphone usage types, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, age, and gender. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.; Serna, C.; Martínez, I.; Cruise, E. Parental Attachment and Peer Relationships in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, G.A.D.; Martin, A.J. Peer relationships and adolescents’ academic and non-academic outcomes: Same-sex and opposite-sex peer effects and the mediating role of school engagement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 81, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, E.; Gardani, M.; McCann, M.; Sweeting, H.; Tranmer, M.; Moore, L. Mental health disorders and adolescent peer relationships. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 253, 112973–112978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahedi, Z.; Saiphoo, A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Stress Health 2018, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, G.; Creaven, A.; Gallagher, S. Stressful life events and adolescent well-being: The role of parent and peer relationships. Stress Health 2020, 36, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, T.; Salmivalli, C.; Idsoe, T. Peer relations as a source of stress? Assessing affiliation- and status-related stress among adolescents. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 8, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C. The Psychological Sense of School Membership among Adolescents: Scale Development and Educational Correlates. Psychol. Sch. 1993, 30, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Ramella, K.; Poulos, A. Building School Connectedness Through Structured Recreation During School: A Concurrent Mixed-Methods Study. J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugene, D.R.; Du, X.; Kim, Y.K. School climate and peer victimization among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of school connectedness and parental involvement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Luo, B.; Huang, C.; Tong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, W.; Zhao, L.; Liao, S. Associations between the number of siblings, parent–child relationship and positive youth development of adolescents in mainland China: A cross-sectional study. Child Care Health Dev. 2024, 50, e13259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Fosco, G.M.; Bray, B.C.; Grych, J.H. Constellations of family closeness and adolescent friendship quality. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Z. Associations between parental emotional warmth, parental attachment, peer attachment, and adolescents’ character strengths. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, J.; Humphrey, N.; Hebron, J. The role of parental and peer attachment relationships and school connectedness in predicting adolescent mental health outcomes. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.F.; Schiamberg, L.B.; Wachs, S.; Huang, Z.; Kamble, S.V.; Soudi, S.; Bayraktar, F.; Li, Z.; Lei, L.; Shu, C. The Influence of Sex and Culture on the Longitudinal Associations of Peer Attachment, Social Preference Goals, and Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Involvement: An Ecological Perspective. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T. Main and Moderated Effects of Moral Cognition and Status on Bullying and Defending. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košir, K.; Klasinc, L.; Špes, T.; Pivec, T.; Cankar, G.; Horvat, M. Predictors of self-reported and peer-reported victimization and bullying behavior in early adolescents: The role of school, classroom, and individual factors. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 35, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wright, M.F. Adolescents’ Social Status Goals: Relationships to Social Status Insecurity, Aggression, and Prosocial Behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsella, E.; Bargh, J.A.; Gollwitzer, P.M. Oxford Handbook of Human Action; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. A New Look at Habits and the Habit-Goal Interface. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 843–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoff, K.; Yu, C.; Kientz, J.; Hiniker, A. What Makes Smartphone Use Meaningful or Meaningless? Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2018, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T.E. Uses and Gratifications Theory in the 21st Century. Mass Commun. Soc. 2000, 3, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, A.; Wood, W. Defining Habit in Psychology. In The Psychology of Habit, 1st ed.; Verplanken, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukopadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet Paradox: A Social Technology That Reduces Social Involvement and Psychological Well-Being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Kiesler, S.; Boneva, B.; Cummings, J.; Helgeson, V.; Crawford, A. Internet Paradox Revisited. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; Choi, M.; Na, E.-Y. Reciprocal longitudinal effects among Korean young adolescent’ negative peer relationships, social withdrawal, and smartphone dependence. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Larsen, H.; Cousijn, J.; Wiers, R.W.; Van Den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Problematic smartphone use and the quantity and quality of peer engagement among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gath, M.; Horwood, L.J.; Gillon, G.; McNeill, B.; Woodward, L.J. Longitudinal associations between screen time and children’s language, early educational skills, and peer social functioning. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konok, V.; Szőke, R. Longitudinal Associations of Children’s Hyperactivity/Inattention, Peer Relationship Problems and Mobile Device Use. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulich, K.N.; Ross, J.M.; Lessem, J.M.; Hewitt, J.K. Screen time and early adolescent mental health, academic, and social outcomes in 9- and 10- year old children: Utilizing the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development SM (ABCD) Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Lai, X.; Zhao, X.; Dai, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Beyond Screen Time: Exploring the Associations between Types of Smartphone Use Content and Adolescents’ Social Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antheunis, M.L.; Schouten, A.P.; Krahmer, E. The Role of Social Networking Sites in Early Adolescents’ Social Lives. J. Early Adolesc. 2016, 36, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjarlais, M.; Joseph, J.J. Socially Interactive and Passive Technologies Enhance Friendship Quality: An Investigation of the Mediating Roles of Online and Offline Self-Disclosure. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J. Online Communication and Adolescent Well-Being: Testing the Stimulation Versus the Displacement Hypothesis. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; McGee, R.; Stanton, W.R. Perceived attachments to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1992, 21, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, A.B.; Nagle, R.J. The influence of parent and peer attachments on life satisfaction in middle childhood and early adolescence. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 66, 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty-Dugas, J.; Ralph, B.C.W.; Oakman, J.M.; Smilek, D. The Relation Between Smartphone Use and Everyday Inattention. Psychol. Conscious. 2018, 5, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.A.; Davidson, B.I.; Shaw, H.; Geyer, K. Do smartphone usage scales predict behavior? Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2019, 130, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, S.; Cross, D.; Shaw, T. Does the nature of schools matter? An exploration of selected school ecology factors on adolescent perceptions of school connectedness. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 80, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.M.; Xiao, B.; Onditi, H.; Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Shapka, J. Measurement invariance and relationships among school connectedness, cyberbullying, and cybervictimization: A comparison among Canadian, Chinese, and Tanzanian adolescents. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2022, 40, 865–879. [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen, T.; Findley-Van Nostrand, D. Social goals, aggression, peer preference, and popularity: Longitudinal links during middle school. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, B. Using Mplus to Do LTA and RI-LTA, Segment 8 [Video]. Mplus Web Talk No.2. (2021, March). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFLggCjILCA (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T. Latent Transition Analysis with Random Intercepts (RI-LTA). Psychol. Methods 2022, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylund, K.; Bellmore, A.; Nishina, A.; Graham, S. Subtypes, Severity, and Structural Stability of Peer Victimization: What Does Latent Class Analysis Say? Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1706–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J.; Peel, D.; Wiley Online Library. Finite Mixture Models; (1. Aufl.;1;); Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, G.; Muthén, B.O. Performance of Factor Mixture Models as a Function of Model Size, Covariate Effects, and Class-Specific Parameters. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, V.; Peebles, A.; Mann, S.; Robb, M.B. Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens, 2021; Common Sense: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzato, P.; Longobardi, C. School climate and connectedness predict problematic smartphone and social media use in Italian adolescents. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2024, 12, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A.; You, S. Effect of Parental Negligence on Mobile Phone Dependency Among Vulnerable Social Groups: Mediating Effect of Peer Attachment. Psychol. Rep. 2019, 122, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty-Dugas, J.; Smilek, D. The relations between smartphone use, mood, and flow experience. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 164, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, E.; Betül Tosuntaş, Ş.; Erzen, E.; Duru, P.; Bostan, N.; Mizrak Şahín, B.; Çulha, Í.; Babadag, B. Determinants of Phubbing, which is the Sum of Many Virtual Addictions: A Structural Equation Model. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V.; Douglas, K.M. The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N. Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 30, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, J.L.; Lansu, T.A.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. A developmental perspective on popularity and the group process of bullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 43, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, S.; Fu, Q.; Zhong, B. Youths’ Habitual Use of Smartphones Alters Sleep Quality and Memory: Insights from a National Sample of Chinese Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnama, S.; Ulfah, M.; Machali, I.; Wibowo, A.; Narmaditya, B.S. Does digital literacy influence students’ online risk? Evidence from COVID-19. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.; Gerosa, T.; Argentin, G.; Losi, L. Mobile media education as a tool to reduce problematic smartphone use: Results of a randomised impact evaluation. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Sehgal, K.; Zieher, A.K.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; et al. The State of Evidence for Social and Emotional Learning: A Contemporary Meta-Analysis of Universal School-Based SEL Interventions. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Habitual Smartphone Use | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Stress | 0.29 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Family Attachment | −0.22 *** | −0.31 *** | 1 | |||||

| 4 School Connectedness | −0.18 *** | −0.28 *** | 0.41 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5 Social Popularity Goal | 0.20 *** | 0.13 *** | −0.04 | 0.01 | 1 | |||

| 6 Social Preference Goal | 0.19 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.03 | 0.10 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | ||

| 7 Peer Attachment Wave 1 | −0.08 ** | −0.16 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.39 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.08 ** | 1 | |

| 8 Peer Attachment Wave 2 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.11 *** | 0.19 *** | −0.09 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.44 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 4.02 | 1.63 | 3.41 | 3.32 | 2.46 | 3.83 | 3.51 | 3.47 |

| SD | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.74 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 1.51 | 1.41 |

| Profiles | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | ||||

| 2 | 61,454.48 | 61,793.49 | 61,583.84 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 60,338.56 | 60,775.16 | 60,505.16 | 0.76 |

| 4 | 59,873.41 | 60,479.51 | 60,104.69 | 0.70 |

| Controlling for demographics | ||||

| 2 | 61,396.94 | 61,797.59 | 61,549.82 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 60,279.33 | 60,818.66 | 60,485.13 | 0.76 |

| 4 | 59,832.14 | 60,582.07 | 60,118.30 | 0.70 |

| Controlling for all covariates | ||||

| 2 | 58,059.37 | 58,530.47 | 58,235.07 | 0.77 |

| 3 | 57,003.54 | 57,662.07 | 57,249.14 | 0.78 |

| 4 | 56,485.52 | 57,402.39 | 56,827.47 | 0.73 |

| Wave 2 Profiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Profiles | Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 |

| Profile 1 | 0.603 | 0.267 | 0.130 |

| Profile 2 | 0.313 | 0.644 | 0.043 |

| Profile 3 | 0.285 | 0.383 | 0.332 |

| Profile 2 vs. Profile 1 | Profile 3 vs. Profile 1 | Profile 3 vs. Profile 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | OR | LCL | UCL | OR | LCL | UCL | OR | LCL | UCL |

| Habitual Smartphone Use | 1.21 | 1.003 | 1.46 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 1.29 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 1.07 |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.82 | 1.31 | 1.12 | 0.90 | 1.41 |

| Female (vs. Male) | 0.80 | 0.53 | 1.19 | 1.15 | 0.63 | 2.09 | 1.44 | 0.81 | 2.57 |

| Asian (vs. White) | 0.83 | 0.51 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 2.61 | 1.63 | 0.84 | 3.17 |

| Other Races (vs. White) | 1.16 | 0.53 | 2.51 | 1.01 | 0.39 | 2.64 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 2.16 |

| Stress | 1.06 | 0.86 | 1.30 | 1.17 | 0.85 | 1.61 | 1.11 | 0.80 | 1.52 |

| Family Attachment | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 1.31 |

| School Connectedness | 0.78 | 0.54 | 1.13 | 1.03 | 0.62 | 1.69 | 1.31 | 0.78 | 2.20 |

| Social Popularity Goal | 1.25 | 0.97 | 1.60 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.83 |

| Social Preference Goal | 0.95 | 0.74 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 0.84 | 1.87 | 1.31 | 0.88 | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Biferie, M.D.; Xiao, B.; Shapka, J. The Longitudinal Association Between Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment: A Random Intercept Latent Transition Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040489

Zhao H, Biferie MD, Xiao B, Shapka J. The Longitudinal Association Between Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment: A Random Intercept Latent Transition Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040489

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Haoyu, Michelle Dusko Biferie, Bowen Xiao, and Jennifer Shapka. 2025. "The Longitudinal Association Between Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment: A Random Intercept Latent Transition Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040489

APA StyleZhao, H., Biferie, M. D., Xiao, B., & Shapka, J. (2025). The Longitudinal Association Between Habitual Smartphone Use and Peer Attachment: A Random Intercept Latent Transition Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040489