Changes in Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Primary School Students: Insights from a Promotion Program in Guatemala

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

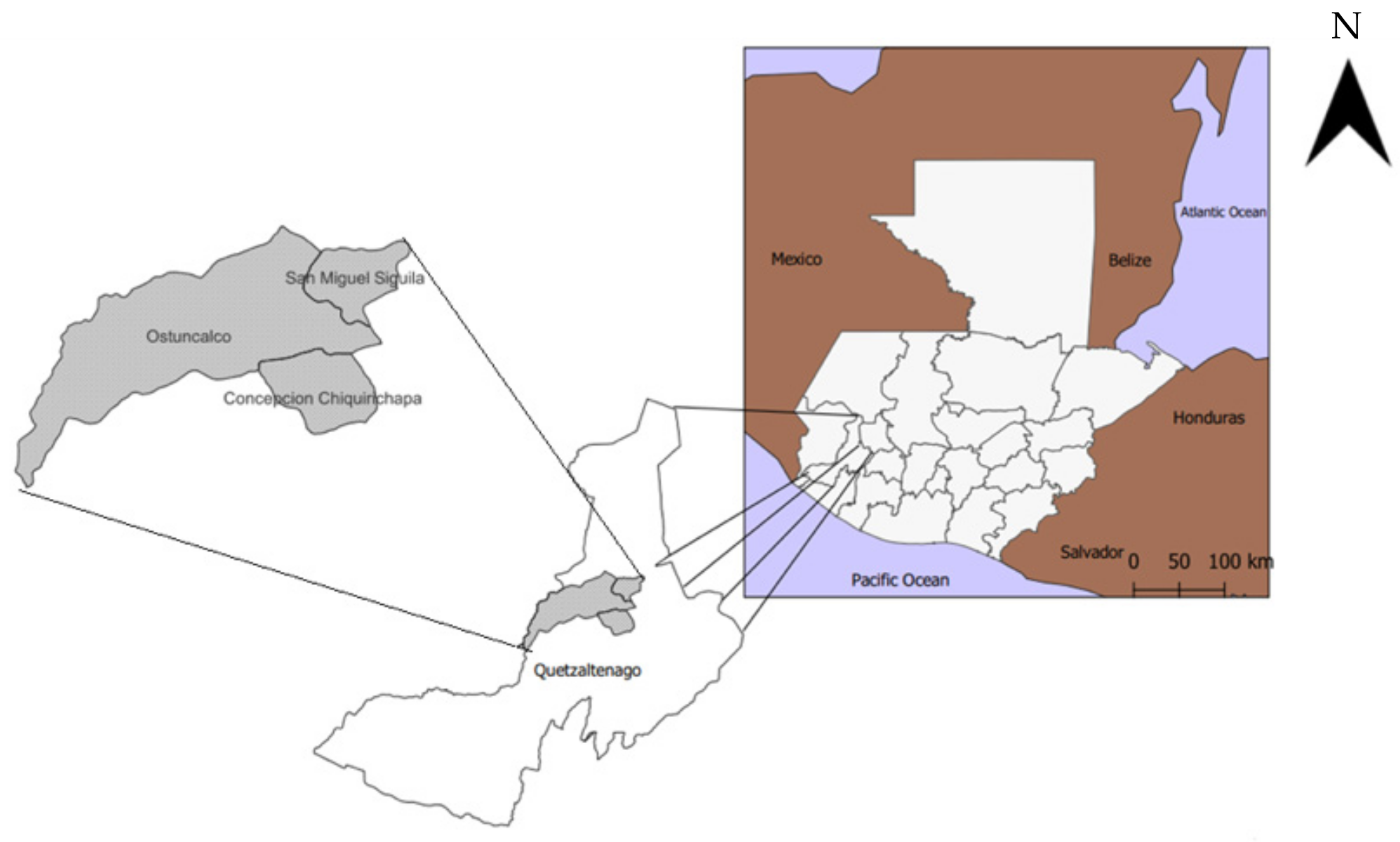

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Evaluation Methods

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Outcomes Measured

2.6. Study Timeline

2.7. Data Collection and Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Information of KAP Survey Participants

3.2. Changes in Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Reported Practices

3.3. Intervention’s Influence on Students’ Hand Hygiene Practices

Participant 5: “Mom and Dad don’t teach them to wash their hands after going to the bathroom, after touching things that are contaminated, so the child grows up in that environment”.

Participant 1: “I have realized, because I live here in the municipality, is that it is because the hygiene measures, the hygienic measures, are not practiced at home. I have seen, let’s say, a farmer who goes to fumigate his potatoes. He goes to fumigate and takes his bag of bread and when he finishes fumigating without washing his hands—considering that he is handling poison—he starts to eat [the bread]. So, since in your house you don’t do it, they don’t worry”.

Participant 3: “Well, I try to wash my hands because I touch a lot of things here in the school. Also, before entering [class], I tell my students, “Let’s wash our hands, my children,” and then they wash their hands. If I am touching books and their things, I try to apply [ABHR] to avoid contamination because the truth is that children have become very sick, and if we do not practice cleanliness, we can get all the viruses in our mouths or noses, or in our eyes”.

Interviewer: “And have you observed any change in students’ hand hygiene because of the little hands and feet they painted, or do they have no impact?”

Participant 1: “Yes, yes, indeed. In fact, as I say, maybe not 100%, but some do [wash their hands]. They look at the images and then act based on the images. It’s a reminder”.

Interviewer: “And do you think students see those little steps, and in some way, does it impact whether they wash their hands or not?”

Participant 2: “No, no, no. I don’t think it does”

Interviewer: “Have you seen if there is any change in student hand hygiene because of the stools?”

Participant 2: “The truth is yes because I see that small children, who used to not be able to wash their hands, sometimes would only wash their little fingers. Now, they reach. They pull the stool, stand up, and wash their hands properly, as it should be”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABHR | Alcohol-based hand rub |

| KAP | Knowledge, attitudes, and practices |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MoE | Ministry of Education of Guatemala |

| UVG | Universidad del Valle de Guatemala |

References

- Alexandrino, A.S.; Santos, R.; Melo, C.; Bastos, J.M. Risk factors for respiratory infections among children attending day care centres. Fam. Pract. 2016, 33, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyle, E.; Davies, H.; Bourhill, J.; Roberts, N.; Lee, J.J.; Albury, C. Effectiveness of hand-hygiene interventions in reducing illness-related absence in educational settings in high income countries: Systematic review and behavioural analysis. J. Public Health 2025, 33, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, H.; Dyer, C.E.; Abdi, I.; Rahman, K.M.; Sun, Y.; Qureshi, M.O.; Dowell-Day, A.; Sward, J.; Islam, M.S. Improving the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19: Examining the factors that influence engagement and the impact on individuals. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care Is Safer Care [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). 2009. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144013/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Freeman, M.C.; Stocks, M.E.; Cumming, O.; Jeandron, A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Wolf, J.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Bonjour, S.; Hunter, P.R.; Fewtrell, L.; et al. Hygiene and health: Systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezezika, O.; Heng, J.; Fatima, K.; Mohamed, A.; Barrett, K. What are the barriers and facilitators to community handwashing with water and soap? A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, R.; Bonell, C.; Jones, H.; Pouliou, T.; Murphy, S.; Waters, E.; Komro, K.; Gibbs, L.; Magnus, D.; Campbell, R. The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollands, G.J.; Shemilt, I.; Marteau, T.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Kelly, M.P.; Nakamura, R.; Suhrcke, M.; Ogilvie, D. Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: Towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, M.M.; Fahsen, N.; Quezada, R.; Pratt, C.; Craig, C.; McDavid, K.; Ocasio, D.V.; Hug, C.; Cordón-Rosales, C.; Lozier, M.J. Assessing hand hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among Guatemalan primary school students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, M.M.; Fahsen, N.; Craig, C.; Quezada, R.; Pratt, C.Q.; Gomez, A.; Brown, T.W.; Kossik, A.; McDavid, K.; Vega Ocasio, D.; et al. Assessment of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Conditions in Public Elementary Schools in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, E.; Hossain, M.K.; Uddin, S.; Venkatesh, M.; Ram, P.K.; Dreibelbis, R. Comparing the behavioural impact of a nudge-based handwashing intervention to high-intensity hygiene education: A cluster-randomised trial in rural Bangladesh. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2018, 23, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakma, S.K.; Hossen, S.; Rakib, T.M.; Hoque, S.; Islam, R.; Biswas, T.; Islam, Z.; Islam, M.M. Effectiveness of a hand hygiene training intervention in improving knowledge and compliance rate among healthcare workers in a respiratory disease hospital. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzikas, A.; Koulierakis, G. A systematic review of nudges on hand hygiene against the spread of COVID-19. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2023, 105, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Kroeger, A.; Hossain, K.; Venkatesh, M.; Ram, P.K. Behavior Change without Behavior Change Communication: Nudging Handwashing among Primary School Students in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caris, M.G.; Labuschagne, H.A.; Dekker, M.; Kramer, M.H.; van Agtmael, M.A.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M. Nudging to improve hand hygiene. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaube, S.; Fischer, P.; Windl, V.; Lermer, E. The effect of persuasive messages on hospital visitors’ hand hygiene behavior. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020, 39, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobekk, H.; Stokke, L. Nudges emphasizing social norms increased hospital visitors’ hand sanitizer use. Behav. Sci. Policy 2020, 6, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, A.M.; Ababu, A.; Bayisa, R.; Abdella, M.; Diriba, E.; Wale, M.; Selam, M.N. Alcohol-Based Handrub Utilization Practice for COVID-19 Prevention Among Pharmacy Professionals in Ethiopian Public Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Drug. Healthc. Patient Saf. 2021, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hernández, K.Y.; Vargas-Guadarrama, L.A.; Vibrans, H. Academic history, domains and distribution of the hot-cold system in Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.Y.; Wang, C.J.; Chiang, T. Childhood Handwashing Habit Formation and Later COVID-19 Preventive Practices: A Cohort Study. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 22, 1390–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-Intervention [n = 109] n (%) | Post-Intervention [n = 144] n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 8 | 10 (9.2) | 5 (3.5) |

| 9 | 24 (22.0) | 29 (20.1) |

| 10 | 36 (33.0) | 32 (22.2) |

| 11 * | 15 (13.8) | 37 (25.7) |

| 12 | 19 (17.4) | 31 (21.5) |

| 13–15 | 5 (4.6) | 10 (7) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 56 (51.4) | 79 (54.9) |

| Female | 53 (48.6) | 65 (45.1) |

| Grade | ||

| 3rd | 27 (24.8) | 35 (24.3) |

| 4th | 35 (32.1) | 34 (23.6) |

| 5th | 27 (24.8) | 39 (27.1) |

| 6th | 20 (18.3) | 36 (25.0) |

| Knowledge Question | Correct Response | Participants Who Responded Correctly | Percentage Point Difference p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention [n = 109] n (%) | Post-Intervention [n = 144] n (%) | |||

| For how many seconds do you think you should wash your hands? | 20 s or more | 58 (53.2) | 88 (61.1) | +7.9 p = 0.21 |

| What materials are needed for hand washing? | Water and soap or alcohol-based hand rub | 103 (94.5) | 144 (100) | +5.5 p < 0.05 |

| Why is hand washing important? | To avoid getting sick or to prevent the transmission of germs/bacteria or to remove dirt | 92 (84.4) | 139 (96.5) | +12.1 p < 0.01 |

| If your hands are dirty, what materials should you use to wash them? | Water and soap | 85 (78.0) | 118 (81.9) | +3.9 p = 0.43 |

| When should you wash your hands? | Before eating or

after coughing or sneezing or after going to the bathroom or after touching something dirty or after playing outside or after eating | 92 (84.4) | 133 (92.4) | +8 p < 0.05 |

| Attitudes Question | Correct Response | Participants Who Responded Correctly | Percentage Point Difference p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention [n = 109] n (%) | Post-Intervention [n = 144] n (%) | |||

| Do you think hand washing is important to prevent diseases? | Yes | 104 (95.4) | 140 (97.2) | +1.8 p = 0.66 |

| Do your friends and family think hand washing is important? | Yes | 100 (91.7) | 139 (96.5) | +4.8 p = 0.10 |

| Do you see your friends or family washing their hands with soap and water? | Yes | 106 (97.2) | 140 (97.2) | 0 >0.99 |

| Do you see your friends or family cleaning their hands with alcohol gel? | Yes | 95 (87.2) | 116 (80.6) | −6.6 p = 0.16 |

| Do you like to wash your hands with soap and water? | Yes * | 109 (100) | 144(100) | No variance |

| Do you like to clean your hands with alcohol gel? | Yes * | 97 (89) | 113 (78.5) | −10.5 p < 0.05 |

| When you are at school and you want to wash your hands, is it easy or difficult? | Easy | 104 (95.4) | 138 (95.8) | +0.4 >0.99 |

| When you are at home and you want to wash your hands, is it easy or difficult? | Easy | 107 (98.2) | 139 (96.5) | −1.7 p = 0.70 |

| Practice Questions | Correct Response | Practices (% of Correct Self-Reported Practices) | Percentage Point Difference p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention [n = 109] n (%) | Post-Intervention [n = 144] n (%) | |||

| Have you washed your hands today? | Yes | 98 (89.9) | 137 (95.1) | +5.2 p = 0.11 |

| What did you use to wash your hands? | Soap and water or alcohol-based hand rub | 90 (82.6) | 135 (93.8) | +11.2 p < 0.01 |

| Do you wash your hands at home? | Yes | 105 (96.3) | 133 (92.4) | −3.9 p = 0.19 |

| Do you wash your hands at school? | Yes | 98 (89.9) | 129 (89.6) | −0.3 p = 0.93 |

| When do you wash your hands? | Before eating or after coughing or sneezing or after going to the bathroom or after touching something dirty or after playing outside or after eating | 93 (85.3) | 137 (95.1) | +9.8 p < 0.01 |

| When you wash your hands, how long does it take you to wash your hands? | 20 s or more | 75 (68.8) | 115 (79.9) | +11.1 p < 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pieters, M.M.; Fahsen, N.; Craig, C.; McDavid, K.; Ishida, K.; Hug, C.; Vega Ocasio, D.; Cordón-Rosales, C.; Lozier, M.J. Changes in Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Primary School Students: Insights from a Promotion Program in Guatemala. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030424

Pieters MM, Fahsen N, Craig C, McDavid K, Ishida K, Hug C, Vega Ocasio D, Cordón-Rosales C, Lozier MJ. Changes in Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Primary School Students: Insights from a Promotion Program in Guatemala. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030424

Chicago/Turabian StylePieters, Michelle Marie, Natalie Fahsen, Christina Craig, Kelsey McDavid, Kanako Ishida, Christiana Hug, Denisse Vega Ocasio, Celia Cordón-Rosales, and Matthew J. Lozier. 2025. "Changes in Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Primary School Students: Insights from a Promotion Program in Guatemala" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030424

APA StylePieters, M. M., Fahsen, N., Craig, C., McDavid, K., Ishida, K., Hug, C., Vega Ocasio, D., Cordón-Rosales, C., & Lozier, M. J. (2025). Changes in Hand Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Primary School Students: Insights from a Promotion Program in Guatemala. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030424