Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

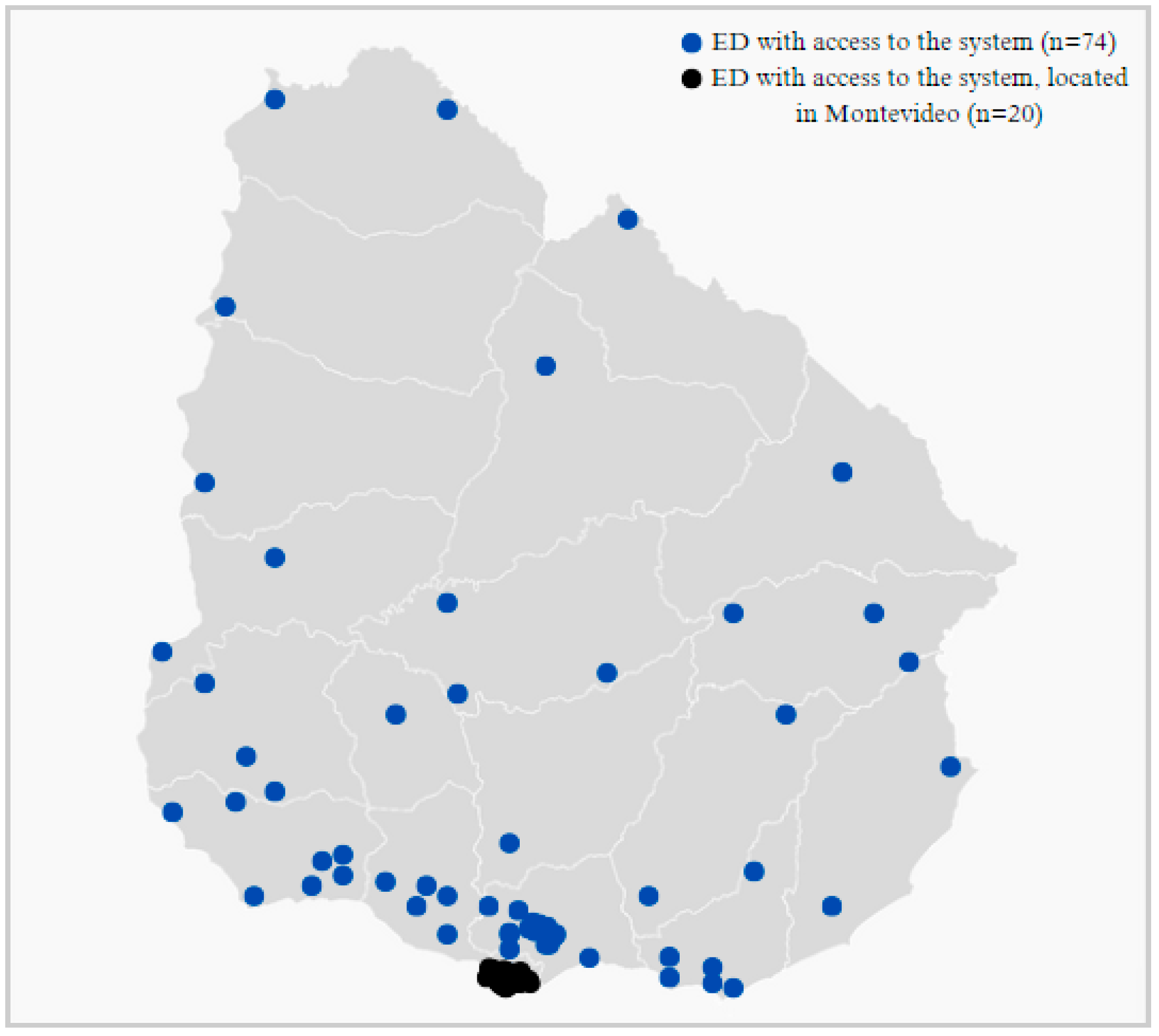

2.1. Setting and Coverage

2.2. Definition of Suicide Attempt

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- All emergency department presentations for suicide attempts;

- Diagnostic confirmation by mental health professional;

- All methods of self-harm with suicidal intent.

- Self-harm without confirmed suicidal intent;

- Suicidal ideation without attempt;

- Accidental injuries;

- Fatal cases (suicides).

2.4. Stages for System Development

2.5. Stages for Implementation

2.6. Ethical Considerations and Data Protection

2.7. Quality Control

3. Results

3.1. National Surveillance System for Suicide Attempt Characteristics

3.2. Implementation Outcomes

3.3. Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 17 de Julio: Día Nacional de Prevención de Suicidio. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/comunicacion/noticias/17-julio-dia-nacional-prevencion-suicidio (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Comisión Nacional Honoraria de Prevención del Suicidio. Estrategia Nacional de Prevención de Suicidio 2021–2025, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Publica: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide—A Global Imperative, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Favril, L.; Yu, R.; Geddes, J.R.; Fazel, S. Individual-level risk factors for suicide mortality in the general population: An umbrella review. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. Manual de Prácticas para el Establecimiento y Mantenimiento de Sistemas de Vigilancia de Intentos de Suicidio y Autoagresiones, 1st ed.; Pan American Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Training Manual for Surveillance of Suicide and Self-Harm in Communities via Key Informants, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Griffin, E.; McMahon, E.; McNicholas, F.; Corcoran, P.; Perry, I.J.; Arensman, E. Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: A 10-year national registry study 2007–2016. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Censo 2023. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/noticias/poblacion-preliminar-3444263-habitantes (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Estimaciones y Proyecciones de la Población de Uruguay: Metodología y Resultados. Revisión 2013, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadistica: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2014.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Informe Cobertura Poblacional del SNIS Según Prestador, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Protocolo de Atención y Seguimiento a las Personas con Intento de Autoeliminación en el Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017.

- Dogmanas, D.; de Álava, L.; Lapetina, A.; Porciúncula, H. Informe Sobre la Implementación del Formulario de Registro Obligatorio de Intentos de Autoeliminación (FRO-IAE); Área Programática para la Atención en Salud Mental-Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2021.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Ley de Protección de Datos Personales (Centro de Información Oficial, Normativa y Avisos Legales del Uruguay, 11/08/2008). Available online: https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/leyes/18331-2008 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. Guía de Práctica Clínica Abordaje de la Conducta Suicida Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Salud Pública: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2024.

- Chung, D.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Wang, M.; Swaraj, S.; Olfson, M.; Large, M. Meta-analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.; Ryan, C.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Singh, S.; Stanton, C.; Large, M.M. Suicide Rates After Discharge from Psychiatric Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, K.; Robinson, J. Sentinel surveillance for self-harm. Crisis 2019, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, R.; Lee, L.; Horan, J.; Milstein, R.; Pertowski, C.; Waller, M.N.; Guidelines Working Group Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: Recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2001, 50, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glasgow, R.; Vogt, T.; Boles, S. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.; Witt, K.; Lamblin, M.; Spittal, M.J.; Carter, G.; Verspoor, K.; Page, A.; Rajaram, G.; Rozova, V.; Hill, N.; et al. Development of a Self-Harm Monitoring System for Victoria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafee, M.; Ahboubi, M.; Shanbehzadeh, M.; Kazemi-Arpanahi, H. Design, development, and evaluation of a surveillance system for suicidal behaviors in Iran. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.; Aron, D.; Keith, R.; Kirsh, S.; Alexander, J.; Lowery, J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| ID number | Random number created to anonymize and protect the identity of the person |

| Country | Country of origin |

| Sex | Sex categorized as female or male |

| Birth date | Birth date (DD/MM/YYYY) |

| Method of self-harm | Method of self-harm (option list includes hanging or suffocation, handgun discharge, self-poisoning by drugs/medicines, intentional self-harm by sharp object, other); only the main method is recorded, prioritizing the most lethal |

| Suicide attempt date | Suicide attempt date (DD/MM/YYYY). |

| Previous suicide attempts | Previous suicide attempts (option list includes yes, no, unknown) |

| In treatment | Whether the person is already receiving mental health treatment (option list includes yes, no) |

| Referral to mental health care | Referral to a mental health professional (option list includes yes, no) |

| Healthcare provider | Patient’s healthcare institution |

| Registration location | Emergency department where the suicide attempt was recorded |

| Registration date | Date of registration (DD/MM/YYYY) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rando, K.; de Álava, L.; Dogmanas, D.; Rodríguez, M.; Irarrázaval, M.; Satdjian, J.L.; Moreira, A. Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030420

Rando K, de Álava L, Dogmanas D, Rodríguez M, Irarrázaval M, Satdjian JL, Moreira A. Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030420

Chicago/Turabian StyleRando, Karina, Laura de Álava, Denisse Dogmanas, Matías Rodríguez, Matías Irarrázaval, Jose Luis Satdjian, and Alejandra Moreira. 2025. "Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030420

APA StyleRando, K., de Álava, L., Dogmanas, D., Rodríguez, M., Irarrázaval, M., Satdjian, J. L., & Moreira, A. (2025). Development and Implementation of National Real-Time Surveillance System for Suicide Attempts in Uruguay. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030420