Construction and Validation of Nursing Actions to Integrate Mobile Care–Educational Technology to Assist Individual in Psychic Distress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

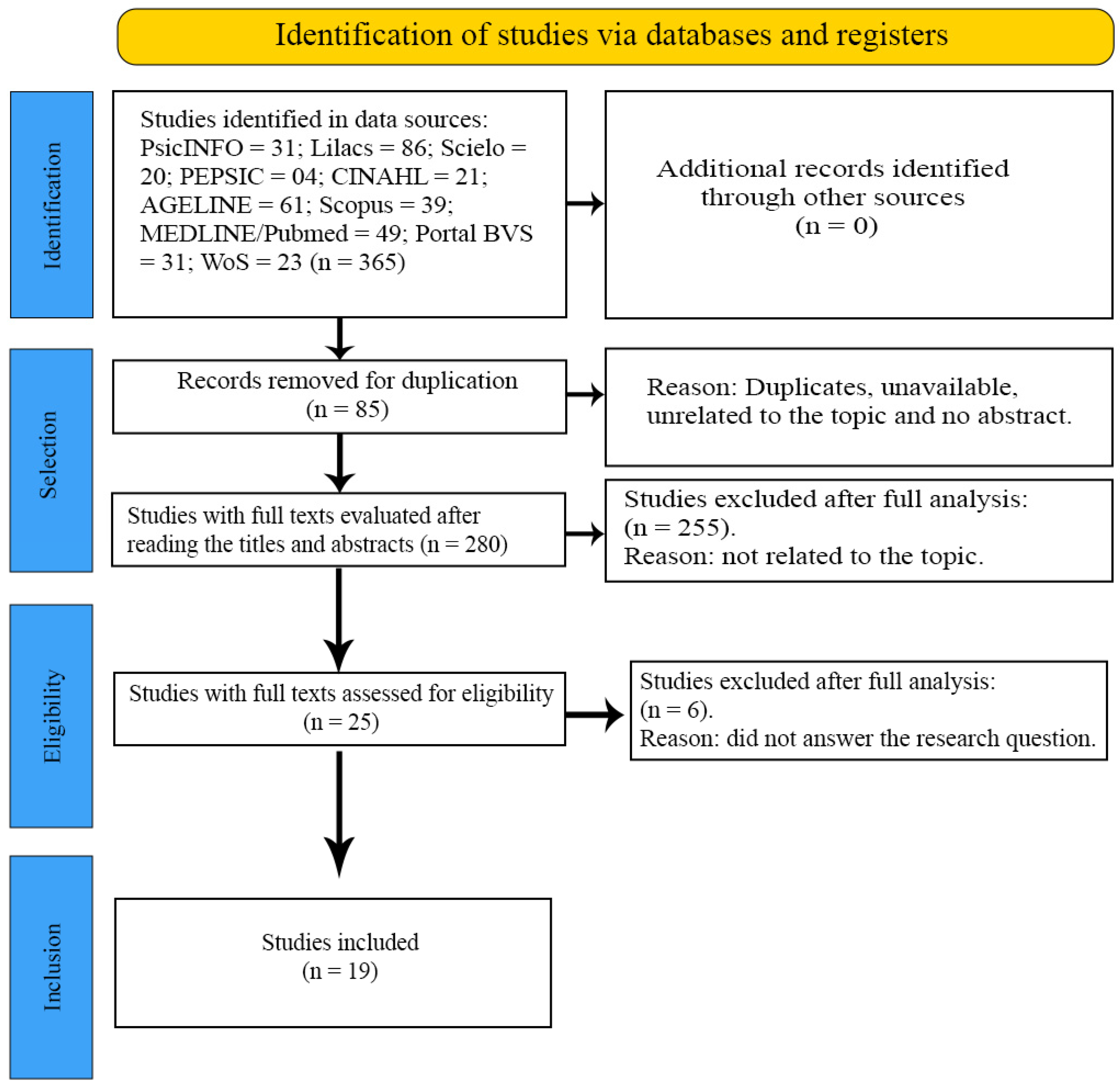

2.2. Step 1—Literature Review

2.3. Step 2—Qualitative Research

2.4. Step 3—Preparation of Nursing Actions (Content)

2.5. Step 4—Content Validation Using the Delphi Technique

2.5.1. Period

2.5.2. Population, Selection Criteria and Sample

2.5.3. Data Collection

2.5.4. Data Analysis and Processing

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Qualitative Research and Preparation of Nursing Actions (Content)

3.3. Content Validation Using the Delphi Technique

3.3.1. Characterization of Experts

3.3.2. Assessment Rounds

4. Discussion

- Implications for nursing and health

- Strengths and limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cassell, E.J. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, B.S.; Pio, D.A.M.; Oliveira, G.T.R. The perspectives of users in psychic suffering about an emergency service. Psychol. Sci. Prof. 2021, 41, e221805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.L.P. Mental disorders record on the Brazilian primary health care information system, 2014. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2016, 25, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.M.J.; Andrade, E.I.G.; Perillo, R.D.; Santos, A.F. Views on mental health assistance in primary care at small cities: Emergence of innovative practices. Interface 2021, 25, e200678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, M.P.S.S.; Fernandes, M.F.T.; Silva, P.F. Application of the therapeutic relationship to people with common mental disorder. Gaúcha J. Nurs. 2017, 38, e63562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nóbrega, M.P.S.S.; Venzel, C.M.M.; Sales, E.S.; Próspero, A.C. Mental health nursing education in Brazil: Perspectives for primary health care. Nurs. Context Text 2020, 29, e20180441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenceslau, L.D.; Ortega, F. Mental health within primary health care and Global Mental Health: International perspectives and Brazilian context. Interface 2015, 19, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbego, C.; Nietsche, E.A.; Teixeira, E.; Girardon-Perlini, N.M.O.; Wild, C.F.; Ilha, S. Care-educational technologies: An emerging concept of the praxis of nurses in a hospital context. Braz. J. Nurs. 2018, 71, 2666–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbego, C.; Nietsche, E.A. Praxis model for technology development: A participatory approach. USP Nurs. Sch. J. 2023, 57, e20230041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344249 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Mateo-Orcajada, A.; Abenza-Cano, L.; Albaladejo-Saura, M.D.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R. Mandatory after-school use of step tracker apps improves physical activity, body composition and fitness of adolescents. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 10235–10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. Ministry of Health. Ordinance No. 3.088, of December 23, 2011. Establishes the Psychosocial Care Network for People with Mental Suffering or Disorders and with Needs Arising from the Use of Crack, Alcohol and Other Drugs, Within the Scope of the Unified Health System. Brasília (DF): Ministry of Health. 2011. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt3088_23_12_2011_rep.html (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Cordeiro, L.; Soares, C.B. Scoping review: Potential for the synthesis of methodologies used in qualitative primary research. BIS Bol. Inst. Saúde (Impr.) 2019, 20, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, D.T.; Delben Gianella, A.C.; Xavier Pellegrini, J.; Fernandes, C.S.; Nóbrega, M.P.S.S. Practices of primary health care nurses in the care for people in psychological distress. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2024, 45, e20230192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, A.C.; Sehnem, S.; Prado, L.L. The use of the Delphi method in the creation of an entrepreneurial and sustainable university model. J. Adm. Soc. Innov. 2023, 9, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Research Methods Foundations; University of Gloucestershire: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/211022791.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Fehring, R.J. Methods to validate nursing diagnoses. Heart Lung 1987, 16, 625–629. [Google Scholar]

- Gante, A.G.C.; Gonzaléz, W.E.S.; Ortega, J.B.; Castillo, J.E.; Fernández, A.S. Likert scale: An alternative to developing and interpreting a social perception instrument. J. High Technol. Soc. 2020, 12, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, N.M.C.; Coluci, M.Z.O. Content validity in the development and adaptation processes of measurement instruments. Sci. Public Health 2011, 16, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.B.; Bezerra, I.C.; Jorge, M.S.B. Mental health care technologies: Primary Care practices and processes. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71 (Suppl. S5), 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.C.B.; Marcon, S.S.; Rodrigues, T.F.C.d.S.; Paiano, M.; Peruzzo, H.E.; Giacon-Arruda, B.C.C.; Pinho, L.B. Mental health assistance in Primary Care: Perspective of professionals from the Family Health Strategy. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75 (Suppl. S3), e20190326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchese, R.; Castro, P.; Ba, S.; Rosalem, V.; Silva, A.; Andrade, M.; Munari, D.; Fernandes, I.; Neves, H. Professional knowledge in primary health care of the person/family in mental distress: Le Boterf perspective. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pinheiro, G.E.W.; Kantorski, L.P. Nurses’ contributions to matrix support in mental health in primary care. Rev. Enferm. UFSM 2021, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, V.V.; Feitosa, L.G.G.C.; Fernandes, M.A.; Almeida, C.A.P.L.; Ramos, C.V. Primary care mental health: Nurses activities in the psychosocial care network. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. S1), e20190104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.M.C.; Costa, N.F.; Barros, D.R.R.E.; Silva-Júnior, J.A.; Silva, J.R.L.; Brito, T.S. Mental health in primary care: Possibilities and weaknesses of receptiono. Rev. Cuid. 2019, 10, e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.B.; Costa, L.S.P.; Jorge, M.S.B. Mental Health Care in the Context of Primary Care: Nursing Contributions. Rev. Baiana Saúde Pública 2019, 43, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotoli, A.; Silva, M.R.S.; Santos, A.M.; Oliveira, A.M.N.; Gomes, G.C. Mental health in Primary Care: Challenges for resolving issues. Esc. Anna Nery 2019, 23, e20180303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiano, A.P.C.; Silva, D.A. Nurses’ perception regarding care for patients with borderline personality disorder. Nursing 2016, 19, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.P.; Nascimento, E.G.C.; Júnior, J.M.P.; Melo, J.A.L. “Behind the mask of madness”: Scenarios and challenges of assisting people with schizophrenia in Primary Care. Fractal Rev. Psicol. 2019, 31, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.J.B.; Santos, M.C.; Tesser, C.D. Perception of Family Health doctors and nurses about the use of auriculotherapy in Mental Health problems. Interface 2022, 26, e210558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.; Luis, M.A.V. Mental health demands: Perception of nurses from family health teams. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2012, 25, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidman, M.A.P.; Marcon, S.S.; Pandini, A.; Bessa, J.B.; Paiano, M. Nursing care for people with mental disorders and their families in Primary Care. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2012, 25, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, D.B.; Bezerra, I.C.; Jorge, M.S.B. Production of mental health care: Territorial practices of the psychosocial network. Trab. Educ. Saúde 2020, 18, e0023167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.B.; Guedes, H.K.A.; Oliveira, T.B.S.; Lima, J.F., Jr. (Re)Building mental health action scenarios in the Family Health Strategy. Rev. Bras. Promoç. Saúde 2011, 24, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gusmão, R.O.M.; Viana, T.M.; Araújo, D.D.; Vieira, J.P.R.; Junior, R.F.S. Role of the mental health nurse in the family health strategy. J. Health Biol. Sci. 2022, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militão, L.F.; Santos, L.I.; Cordeiro, G.F.T.; Sousa, K.H.J.F.; Peres, M.A.A.; Peters, A.A. Users of psychoactive substances: Challenges to nursing care in the Family Health Strategy. Esc. Anna Nery 2022, 26, e20210429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.J.; Ferreira, L.A.; Zuffi, F.B.; Cardoso, R.J.; Rezende, M.P.; Mendonça, G.S.; Dias, E.P. Psychiatric client embracement on primary health care. Biosci. J. 2015, 31, 1279–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsoni, E.B.; Heusy, I.P.M.; Silva, Z.F.; Padilha, M.I.; Rodrigues, J. Mental health nursing consultations in primary health care. SMAD. Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Ment. Alcool Drog. 2015, 11, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluci, M.Z.O.; Alexandre, N.M.C.; Milani, D. Construction of measurement instruments in the area of health. Sci. Public Health 2015, 20, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.K.; Mendes, D.C.O.; Silva, G.C.L.; Vedana, K.G.G.; Scorsolini-Comin, F.; Fiorati, R.C.; Ferreira, L.V.C. Perceptions of nurses in basic health units regarding their actions in cases of depression. Cogitare Nurs. 2023, 28, e92825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.; Willhelm, A.R.; Koller, S.H.; Almeida, R.M.M. Risk and protective factors for suicide attempt in emerging adulthood. Sci. Public Health 2018, 23, 3767–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.P.R.O.; Santos, H.L.P.C.; Maciel, F.B.M.; Manfro, E.C.; Prado, N.M.B.L. Risk factors and suicide prevention in Primary Health Care during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review of the literature. Braz. J. Fam. Community Med. 2022, 17, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Ministry of Health. Mental Health. Primary Care Booklets, nº34. Brasília (DF): Ministry of Health. 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cadernosatencaobasica34saudemental.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Silveira, J.O.; Sena, L.O.; Santos, N.O.; Tisott, Z.L.; Marchiori, M.R.C.T.; Soccol, K.L.S. Health care for people who make drug abuse in family health strategies: Literature review. Discip. Sci. Ser. Health Sci. 2021, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzatti, M. Approach to grief in primary health care. Braz. J. Fam. Community Med. 2023, 18, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, R. Grief Is Another Word for Love, 1st ed.; Ágora: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.M.; Narciso, A.C.; Evangelista, C.B.; Filgueiras, T.F.; Costa, M.M.L.; Cruz, R.A.O. Nurses’ Experiences with Palliative Care. Online Res. J. 2020, 12, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucolo, D.F.; Perroca, M.G. Instrument to assess the nursing care product: Development and content validation. Lat. Am. J. Nurs. 2015, 23, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, C.; Vargas, D.; Pereira, C.F. Mental health nursing interventions in Primary Health Care: Scoping review. Acta Paul Nurs. 2022, 35, eAPE01506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.S.; Llapa-Rodriguez, E.O.; Bispo, L.D.G.; de Andrade, J.S.; Barreiro, M.D.S.C.; de Resende, L.T.; Rodrigues, I.D.C.V. Construction and validation of a clinical simulation on HIV testing and counseling in pregnant women. Cogitare Nurs. 2022, 27, e80433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (S) | Database/Country of Origin | Year | Title of Study | Authors | Nature of Study/Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 [24] | Web of Science/Brazil | 2018 | Mental health care technologies: primary care practices and processes | Campos DB, Bezerra IC, Jorge MSB/ Rev. Bras. Enferm | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/06 nurses |

| S3 [25] | Cinahl/Brazil | 2022 | Mental health assistance in primary care: the perspective of professionals from the family health strategy. | Cardoso LCB, Marcon SS, Rodrigues TFCS, Paiano M, Peruzzo HE, Giacon-Arruda BCC et al./Rev. Bras. Enferm | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/29 professionals from multi-professional teams |

| S2 [26] | Lilacs/ Brazil | 2014 | Professional knowledge in primary health care of the person/family in mental distress: le boterf perspective | Lucchese R, Castro P, Ba S, Rosalem V, Silva A, Andrade M et al./REEUSP | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/33 professionals from a multi-professional team |

| S4 [27] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2021 | Nurses’ contributions to matrix support for mental health in primary care. | Pinheiro GEW, Kantorski LP/Rev. Enferm. UFSM | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/15 professionals from multi-professional teams |

| S5 [28] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2020 | Primary care mental health: nurses activities in the psychosocial care network. | Nunes VV, Feitosa LGGC, Fernandes MA, Almeida CAPL, Ramos CV/REBEn | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/20 nurses |

| S6 [29] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2019 | Mental health in primary care: possibilities and weaknesses of reception. | Silva PMC, Costa NF, Barros DRRE, Silva Júnior JA, Silva JRL, Brito TS. Rev Cuidarte | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/20 nurses |

| S7 [30] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2019 | Mental health care in the context of primary care: nursing’s contributions. | Sousa SB, Costa LSP, Jorge MSB/Rev Baiana de Saúde Pública | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/07 nurses |

| S8 [31] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2019 | Mental health in Primary Care: challenges for the resoluteness of actions | Rotoli A, Silva MRS, Santos AM, Oliveira AMN, Gomes GC/Esc Anna Nery | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/30 professionals from a multi-professional team |

| S09 [32] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2016 | Nurses’ perception of care for people with borderline disorder | Cassiano APC, Silva RG, Almeida CL, Silva DA/Nursing (Sao Paulo) | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/07 nurses |

| S10 [33] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2019 | “Behind the mask of madness”: scenarios and challenges of care for people with schizophrenia in primary care. | Silva AP, Nascimento EGC, Júnior JMP, Melo JAL. Fractal/Rev. Psicol | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/10 professionals from multi-professional teams |

| S11 [34] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2022 | Perception of family health doctors and nurses on the use of auriculotherapy in Mental health problems | Silva FJB, Santos MC, Tesser CD/Interface (Botucatu) | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/44 professionals from a multi-professional team |

| S12 [35] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2012 | Mental health demands: perception of family health team nurses | Souza J, Luis MAV/Acta Paul Enferm | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/05 nurses |

| S13 [36] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2012 | Nursing care for people with mental disorders and their families in primary care | Waidman MAP, Marcon SS, Pandini A, Bessa JB, Paiano M/Acta paul Enferm | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/17 nurses |

| S14 [37] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2020 | Producing mental health care: territorial practices in the psychosocial network | Campos DB, Bezerra IC, Jorge, MSB/Trab. educ. saúde | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/60 professionals from multi-professional teams |

| S16 [38] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2011 | (Re) Building mental health scenarios in the Family Health Strategy | Oliveira FB de, Guedes HKA, Oliveira TBS de, Junior JFL./Rev. | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/13 nurses |

| S17 [39] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2022 | The role of nurses in mental health in the family health strategy | Gusmão ROM, Viana TM, Araújo DD, Vieira JPR, Junior RFS/J. Health Biol. Sci. (Online) | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/07 nurses |

| S18 [40] | Lilacs/Brazil | 2022 | Users of psychoactive substances: challenges for nursing care in the Family Health Strategy. | Militão LF, Santos LI, Cordeiro GFT, Sousa KHJF, Peres MAA, Peters AA/Esc. Anna. Nery | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/07 nurses |

| S15 [41] | Scopus/Brazil | 2015 | Psychiatric client embracement on primary health care | Silva JA, Ferreira LA, Zuffi FB., Cardoso RJ., Rezende MP, Mendonça GS/Bosci. J. | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/26 nurses |

| S19 [42] | Pepsic/Brazil | 2015 | Mental health nursing consultation in primary health care | Bolsoni EB, Heusy IPM, Silva ZF, Padilha MI, Rodrigues J/SMAD, Electronic Journal of Mental Health Alcohol Drugs | Original, descriptive and qualitative research/07 nurses |

| N (%) | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Social Profile | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 15 (93.8) | |

| Male | 1 (6.3) | |

| Age Range | 8.44 | |

| 20–59 years old | 15 (93.8) | |

| ≥60 years old | 1 (6.3) | |

| Academic Profile | ||

| Graduation Completion | 8.79 | |

| Specialization/Residency: | ||

| Mental and Psychiatric Health | 13 (81.3) | |

| Collective Health | 2 (12.5) | |

| Public Health | 1 (6.3) | |

| Master’s Degree: | ||

| Mental and Psychiatric Health | 11 (68.8) | |

| Collective Health | 4 (25.0) | |

| Public Health | 1 (6.3) | |

| Doctorate Degree: | ||

| Mental and Psychiatric Health | 10 (76.9) | |

| Collective Health | 2 (15.4) | |

| Public Health | 1 (7.7) | |

| Post-doctoral: | ||

| No | 11 (68.8) | |

| Yes | 5 (31.3) | |

| Time in clinical-care as a Specialist | 8.00 | |

| Time in clinical-assistance as a Master | 6.67 | |

| Time in clinical-assistance as a Doctor | 6.15 | |

| Time in teaching and research as a Specialist | 11.63 | |

| Time in teaching and research as a Master | 8.02 | |

| Time in teaching and research as a Doctor | 5.86 | |

| Member of Scientific Society/Department/Chapter | ||

| Mental and Psychiatric Health | 9 (56.3) | |

| Collective Health | 1 (6.3) | |

| Public Health | 1 (6.3) | |

| Not a member of a Scientific Society/Department/Chapter in the thematic area | 5 (31.3) | |

| Experience with construction studies and product validation | ||

| No | 7 (43.8) | |

| Yes | 9 (56.3) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendes, D.T.; Tibúrcio, P.d.C.; Cirqueira, G.d.M.; Marcheti, P.M.; Zerbetto, S.R.; Fernandes, C.S.; Nóbrega, M.d.P.S.d.S. Construction and Validation of Nursing Actions to Integrate Mobile Care–Educational Technology to Assist Individual in Psychic Distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030419

Mendes DT, Tibúrcio PdC, Cirqueira GdM, Marcheti PM, Zerbetto SR, Fernandes CS, Nóbrega MdPSdS. Construction and Validation of Nursing Actions to Integrate Mobile Care–Educational Technology to Assist Individual in Psychic Distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030419

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendes, Dárcio Tadeu, Priscila de Campos Tibúrcio, Geni da Mota Cirqueira, Priscila Maria Marcheti, Sonia Regina Zerbetto, Carla Sílvia Fernandes, and Maria do Perpétuo Socorro de Sousa Nóbrega. 2025. "Construction and Validation of Nursing Actions to Integrate Mobile Care–Educational Technology to Assist Individual in Psychic Distress" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030419

APA StyleMendes, D. T., Tibúrcio, P. d. C., Cirqueira, G. d. M., Marcheti, P. M., Zerbetto, S. R., Fernandes, C. S., & Nóbrega, M. d. P. S. d. S. (2025). Construction and Validation of Nursing Actions to Integrate Mobile Care–Educational Technology to Assist Individual in Psychic Distress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030419