Spirituality, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Use of Complementary Medicine in Vaccine Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Demographics

2.3. Spirituality

2.4. Vaccination and Vaccination Perception

2.5. Putative Predictors of Spirituality and Perceived Harmfulness of Vaccination (Independent Variables)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

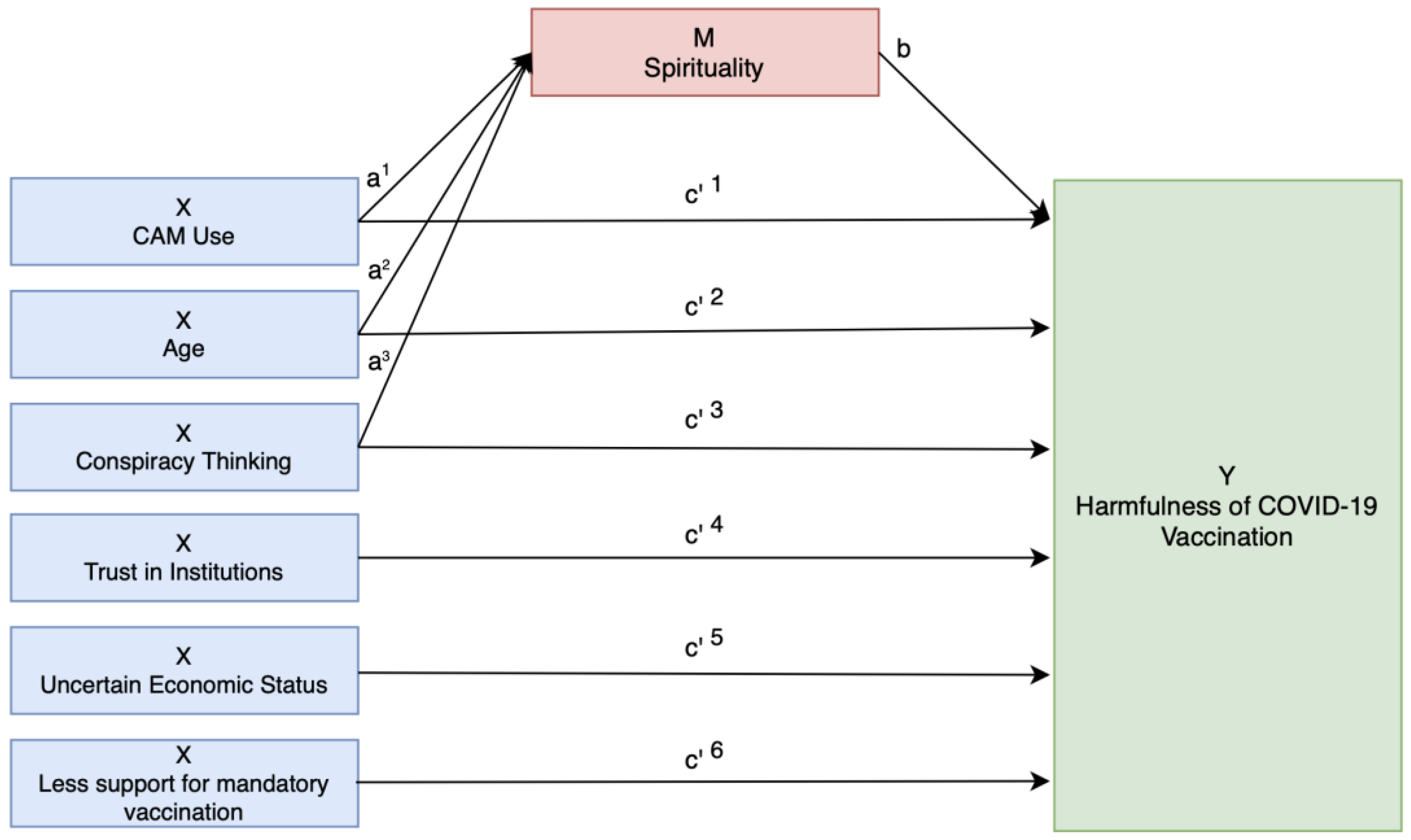

Mediation Model Overview

- Predictors must show significant associations with the perceived harmfulness of the COVID-19 vaccination;

- Predictors must also show significant associations with spirituality;

- Both predictors and spirituality significantly predicted the dependent variable in a regression model.

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate, Psychometric Properties, and Associations with Vaccination Perceptions

3.2. Sample Characteristics, Spirituality, and Perceived Vaccination Harmfulness

3.3. Spirituality and Attitudes Toward COVID-19 and Mandatory Childhood Vaccinations

3.4. Predictors of Spirituality and Perceived Harmfulness of COVID-19 and Mandatory Childhood Vaccinations

3.5. Mediation Analysis of Spirituality in Perceived Harmfulness of COVID-19 Vaccination

Mediation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.2. Study Aims and Interpretation of Findings

4.3. Implications for Public Health and Future Research

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torskenæs, K.B.; Kalfoss, M.H.; Sæteren, B. Meaning given to Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs: Explored by a Sample of a Norwegian Population. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 3355–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilmaghani, M. Importance of Religion or Spirituality and Mental Health in Canada. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroope, S.; Kent, B.V.; Zhang, Y.; Kandula, N.R.; Kanaya, A.M.; Shields, A.E. Self-Rated Religiosity/Spirituality and Four Health Outcomes Among US South Asians: Findings From the Study on Stress, Spirituality, and Health. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.; Teixeira, L.; Esteves, R.; Ribeiro, F.; Pereira, F.; Teixeira, A.; Magalhães, C. Spirituality and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Path Analysis Model. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboni, T.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Doan-Soares, S.D.; Long, K.N.G.; Ferrell, B.R.; Fitchett, G.; Koenig, H.G.; Bain, P.A.; Puchalski, C.; Steinhauser, K.E.; et al. Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA 2022, 328, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Baumann, K. Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness. Religions 2018, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Dienberg, T. Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Franciscan-Inspired Spirituality and Their Associations with Compassion and Altruism in Franciscan Brothers and Sisters. Religions 2018, 9, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A. Spiritual Experiences, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Yoga Practitioners: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study in Germany. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2024, 34, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratta, P.; Capanna, C.; Riccardi, I.; Perugi, G.; Toni, C.; Dell’Osso, L.; Rossi, A. Spirituality and Religiosity in the Aftermath of a Natural Catastrophe in Italy. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, S.; Anugwom, G.O.; Basiru, T.; Sachdeva, V.; Muhammad, N.; Bachu, A.; Trudeau, M.; Gulati, G.; Sullivan, A.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Bridging Science and Spirituality: The Intersection of Religion and Public Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1183234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madran, B.; Kayı, İ.; Beşer, A.; Ergönül, Ö. Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines among Healthcare Workers and the Effect of Nudging Interventions: A Mixed Methods Study. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4586–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Beerenbrock, Y. Attitudes of Yoga Practitioners Toward COVID-19 Virus Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Germany. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2022, 32, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; MacDonald, N.; Bocquier, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P. Underlying Factors Impacting Vaccine Hesitancy in High Income Countries: A Review of Qualitative Studies. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCready, J.L.; Nichol, B.; Steen, M.; Unsworth, J.; Comparcini, D.; Tomietto, M. Understanding the Barriers and Facilitators of Vaccine Hesitancy towards the COVID-19 Vaccine in Healthcare Workers and Healthcare Students Worldwide: An Umbrella Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioffi, A.; Cecannecchia, C. Compulsory Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in Health Care Professionals in Italy: Bioethical-Legal Issues. Med. Sci. Law 2023, 63, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjens, B.T.; van der Lee, R. Spiritual Skepticism? Heterogeneous Science Skepticism in the Netherlands. Public. Underst. Sci. 2020, 29, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, J.P.; Rutjens, B.T. Spirituality and Religiosity Contribute to Ongoing COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: Comparing 195 Regions around the World. Vaccine X 2022, 12, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzeczna, N.; Bertlich, T.; Većkalov, B.; Rutjens, B.T. Spirituality Is Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Scepticism. Vaccine 2023, 41, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosarkova, A.; Malinakova, K.; van Dijk, J.P.; Tavel, P. Vaccine Refusal in the Czech Republic Is Associated with Being Spiritual but Not Religiously Affiliated. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syiroj, A.T.R.; Pardosi, J.F.; Heywood, A.E. Exploring Parents’ Reasons for Incomplete Childhood Immunisation in Indonesia. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6486–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreidl, P.; Morosetti, G. Do we have to expect an epidemic of measles in the near future in Southern Tyrol? Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. Suppl. 2003, 115, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Steininger, R. South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century (Studies in Austrian and Central European History and Culture); Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Ausserhofer, D.; Plagg, B.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Wiedermann, W.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy during the Coronavirus Pandemic in South Tyrol, Italy: Linguistic Correlates in a Representative Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Trust in Conventional Healthcare and the Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in South Tyrol, Italy: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Ann. Ig. 2024, 36, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, A.; Rodrigues Recchia, D.; Hein, R.; Dienberg, T. Perceived Changes of Specific Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviors during the Corona Pandemic and Their Relation to Wellbeing. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesinstitut für Statistik der Autonomen Provinz Bozen—Südtirol COVID-19: Einstellungen und Verhalten der Bürger. Jänner 2021; astatinfo; Landesverwaltung der Autonomen Provinz Bozen—Südtirol: Bolzano, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/de/default.asp (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Basha, S.; Salameh, B.; Basha, W. Sicily/Italy COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO Sicily/Italy): Monitoring Knowledge, Risk Perceptions, Preventive Behaviours, and Public Trust in the Current Coronavirus Outbreak in Sicily/Italy. PsychArchives 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Wieler, L.; Bosnjak, M.; Ramharter, M.; Stollorz, V.; Omer, S.; Korn, L.; Sprengholz, P.; Felgendreff, L.; Eitze, S.; et al. Germany COVID-19 Snapshot MOnitoring (COSMO Germany): Monitoring Knowledge, Risk Perceptions, Preventive Behaviours, and Public Trust in the Current Coronavirus Outbreak in Germany. Available online: https://www.psycharchives.org/index.php/en/item/e5acdc65-77e9-4fd4-9cd2-bf6aa2dd5eba (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Büssing, A. Wondering Awe as a Perceptive Aspect of Spirituality and Its Relation to Indicators of Wellbeing: Frequency of Perception and Underlying Triggers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 738770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Lombardo, S.; Piccoliori, G.; Gärtner, T.; Engl, A. Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Mistrust during Pandemic Decline: Findings from 2021 and 2023 Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Vaccines 2024, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, S.D.; Raeke, L.H. Patients’ Trust in Physicians: Many Theories, Few Measures, and Little Data. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, M.E.; Hershey, J.C.; Bradlow, E.T. Promises and Lies: Restoring Violated Trust. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2006, 101, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, M.; Haffke, P.; Neave, N.; Nouripanah, N.; Imhoff, R. Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eardley, S.; Bishop, F.L.; Cardini, F.; Santos-Rey, K.; Jong, M.C.; Ursoniu, S.; Dragan, S.; Hegyi, G.; Uehleke, B.; Vas, J.; et al. A Pilot Feasibility Study of a Questionnaire to Determine European Union-Wide CAM Use. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2012, 19, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, M.L.; Schmidt, S.; Güthlin, C. Translation and Adaptation of an International Questionnaire to Measure Usage of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (I-CAM-G). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, E.; Peer, E. Attribute Framing Affects the Perceived Fairness of Health Care Allocation Principles. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arof, K.Z.M.; Ismail, S.; Saleh, A.L. Contractor’s Performance Appraisal System in the Malaysian Construction Industry: Current Practice, Perception and Understanding. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universität Zürich Kruskal-Wallis-Test. Available online: https://www.methodenberatung.uzh.ch/de/datenanalyse_spss/unterschiede/zentral/kruskal.html (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Akoglu, H. User’s Guide to Correlation Coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, E.; Jaggi, S.; Gills, R.; Jayasankar, J. IBM SPSS Statistics: An Overview; ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute: Kochi, India, 2023; pp. 62–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, C.; Jusufoska, M.; Tolic, J.; Abreu de Azevedo, M.; Tarr, P.E.; Deml, M.J. Pharmacists’ Approaches to Vaccination Consultations in Switzerland: A Qualitative Study Comparing the Roles of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) and Biomedicine. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, G.M.; Browne, M.; Rockloff, M.; Unsworth, C. Anti-Vaccination and pro-CAM Attitudes Both Reflect Magical Beliefs about Health. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deml, M.J.; Notter, J.; Kliem, P.; Buhl, A.; Huber, B.M.; Pfeiffer, C.; Burton-Jeangros, C.; Tarr, P.E. “We Treat Humans, Not Herds!”: A Qualitative Study of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Providers’ Individualized Approaches to Vaccination in Switzerland. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 240, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Jones, J.; Browne, M.; Leslie, S.J. Psychosocial Factors That Predict Why People Use Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Continue with Its Use: A Population Based Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Jones, J.; Browne, M.; Leslie, S.J. Why People Seek Complementary and Alternative Medicine before Conventional Medical Treatment: A Population Based Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, J.E.; McKenzie, K.; Janosi, J.; Forssman, B.; Sullivan, E.; Wiley, K. The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Practitioners in the Information-Seeking Pathway of Vaccine-Hesitant Parents in the Blue Mountains Area, Australia. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, e368–e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, P.D. Initial Assessment of a Brief Health, Fitness, and Spirituality Survey for Epidemiological Research: A Pilot Study. J. Lifestyle Med. 2022, 12, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G.; Hamilton, J.B.; Doolittle, B.R. Training to Conduct Research on Religion, Spirituality and Health: A Commentary. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 2178–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, D.; Seccaraccia, D.; Huth, J.; Kurppa, K.; Fitch, M. Patient versus Health Care Provider Perspectives on Spirituality and Spiritual Care: The Potential to Miss the Moment. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2017, 6, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.; Thomson, P.; Rockloff, M.J.; Pennycook, G. Going against the Herd: Psychological and Cultural Factors Underlying the “Vaccination Confidence Gap”. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, T.; Kloos, C.; Mueller, N.; Roemelt, J.; Keinki, C.; Wolf, G.; Mueller, U.A.; Huebner, J. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Is Positively Associated with Religiousness/Spirituality. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhausen-Wachowsky, A.; Martin, D.; Rodrigues Recchia, D.; Büssing, A. Stability of Psychological Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic among People with an Anthroposophical Worldview: The Influence of Wondering Awe and Perception of Nature as Resources. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1200067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedinger, A.; Siegers, P. Religion, Spirituality, and Susceptibility to Conspiracy Theories: Examining the Role of Analytic Thinking and Post-Critical Beliefs. Politics Relig. 2024, 17, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, Ž.; Kovačević, E.; Šuljok, A. Health Literacy, Religiosity, and Political Identification as Predictors of Vaccination Conspiracy Beliefs: A Test of the Deficit and Contextual Models. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanat, Z. Poland’s Vaccine Skeptics Create a Political Headache. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-vaccine-skeptic-vax-hesitancy-political-trouble-polish-coronavirus-covid-19/ (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Herzig van Wees, S.; Abunnaja, K.; Mounier-Jack, S. Understanding and Explaining the Link between Anthroposophy and Vaccine Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibongani Volet, A.; Scavone, C.; Catalán-Matamoros, D.; Capuano, A. Vaccine Hesitancy Among Religious Groups: Reasons Underlying This Phenomenon and Communication Strategies to Rebuild Trust. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 824560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruijs, W.L.; Hautvast, J.L.; Kerrar, S.; van der Velden, K.; Hulscher, M.E. The Role of Religious Leaders in Promoting Acceptance of Vaccination within a Minority Group: A Qualitative Study. BMC Public. Health 2013, 13, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handayani, S.; Rias, Y.A.; Kurniasari, M.D.; Agustin, R.; Rosyad, Y.S.; Shih, Y.W.; Chang, C.W.; Tsai, H.T. Relationship of Spirituality, Health Engagement, Health Belief and Attitudes toward Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoncello, C.; Ferro, A.; Fonzo, M.; Zanovello, S.; Napoletano, G.; Russo, F.; Baldo, V.; Cocchio, S. Socioeconomic Determinants in Vaccine Hesitancy and Vaccine Refusal in Italy. Vaccines 2020, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n = 1388 | GrAw-7 Spirituality Scale | Sum Score for Harmfulness of COVID-19 Vaccination | Sum Score for Harmfulness of Mandatory Childhood Vaccination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Spearman-rho a | Spearman-rho a | Spearman-rho a | |

| Age | 50.3 ± 17.48 | 0.108 *** | −0.107 *** | −0.058 * |

| Conspiracy thinking | 16.44 ± 6.45 | 0.122 *** | 0.422 *** | 0.390 *** |

| Altruism | 20.25 ± 5.24 | 0.250 *** | 0.015 (n.s.) | −0.003 (n.s.) |

| Well-being | 10.91 ± 2.94 | 0.191 *** | −0.064 * | −0.074 * |

| Trust in institutions | 30.51 ± 9.54 | 0.035 (n.s.) | −0.516 *** | −0.484 *** |

| Trust in media | 12.29 ± 4.85 | −0.063 * | −0.340 *** | −0.247 *** |

| % | effect size (p-value b) mean | effect size (p-value b) mean | effect size (p-value b) mean | |

| Gender | 0.18 *** | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Female | 51.0 | 60.4 | 11.6 | 8.1 |

| Male | 49.0 | 53.7 | 11.8 | 8.2 |

| Education | n.s. | 0.12 *** | 0.11 *** | |

| Middle school or lower | 18.1 | 56.1 | 11.1 | 8.2 |

| Vocational school | 28.8 | 55.0 | 12.0 | 8.8 |

| High school | 31.4 | 58.2 | 12.0 | 8.3 |

| University | 21.8 | 56.6 | 10.7 | 7.3 |

| Residence | n.s. | 0.075 ** | 0.054 * | |

| Urban | 40.5 | 57.2 | 11.1 | 7.8 |

| Rural | 59.5 | 57.0 | 12.1 | 8.4 |

| Citizenship | 0.054 * | n.s. | 0.055 * | |

| Italian | 90.2 | 57.5 | 11.7 | 8.1 |

| Other | 9.8 | 52.9 | 11.9 | 8.3 |

| Native Language ‡ | 0.071 * | n.s. | 0.094 * | |

| German | 63.1 | 57.4 | 11.9 | 8.3 |

| Italian | 27.1 | 57.2 | 11.2 | 7.7 |

| Ladin | 3.7 | 61.4 | 11.5 | 7.3 |

| Other/more than one | 6.1 | 51.0 | 11.7 | 9.1 |

| Working in the health sector | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Yes | 7.3 | 59.4 | 11.8 | 7.3 |

| No | 92.7 | 56.9 | 11.7 | 8.1 |

| Chronic disease(s) | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Yes | 18.2 | 58.7 | 11.5 | 7.9 |

| No | 81.8 | 56.7 | 11.7 | 8.2 |

| Economic situation (last 3 months) | n.s. | 0.16 *** | 0.17 * | |

| Better | 5.0 | 57.6 | 11.8 | 8.2 |

| The same | 66.9 | 57.7 | 11.1 | 7.5 |

| Worse | 25.2 | 55.4 | 13.1 | 9.6 |

| Don’t know | 2.9 | 48.4 | 13.6 | 10.4 |

| CAM consultation | 0.12 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.13 *** | |

| Yes | 21.2 | 61.86 | 13.6 | 9.5 |

| No | 78.8 | 55.80 | 11.2 | 7.8 |

| GP consultation | n.s. | −0.053 * | 0.084 ** | |

| Yes | 81.7 | 57.58 | 11.6 | 8.0 |

| No | 18.3 | 54.93 | 12.2 | 9.1 |

| Trust in vaccination staff | n.s. | 0.40 *** | 0.383 *** | |

| (Rather) Yes | 64.7 | 57.37 | 10.1 | 6.8 |

| (Rather) No | 30.8 | 57.37 | 14.8 | 10.7 |

| Don’t know | 4.5 | 51.1 | 13.5 | 10.4 |

| Did the pandemic change your opinion about mandatory childhood vaccination? | 0.08 ** | 0.36 *** | 0.42 *** | |

| Yes, I support it more now | 15.1 | 60.7 | 10.0 | 6.9 |

| Yes, I support it less now | 9.6 | 58.7 | 18.1 | 15.3 |

| No | 75.3 | 56.2 | 11.2 | 7.5 |

| Category | Question | COVID-19 Vaccination | Mandatory Childhood Vaccination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Rather) Agree % | Spirituality (Mean) | Effect Size (p-Value a) | (Rather) Agree % | Spirituality (Mean) | Effect Size (p-Value a) | ||

| Trust in Authorities | I think that decisions about vaccination made by the public authorities are right | 60 | 56.5 | 0.05 (**) | 60 | 56.5 | 0.06 (**) |

| Perceived Unnecessity | Vaccination is not necessary because … | ||||||

| … it is not effective | 21 | 59.2 | 0.075 (**) | 13 | 57.6 | n.s. | |

| … natural herd immunity/immune system is quite sufficient | 21 | 59.6 | 0.08 (**) | 15 | 59.13 | n.s. | |

| … this disease does not/no longer exist | 5 | 54.7 | n.s. | 9 | 58.01 | n.s. | |

| … the whole thing is only a profit for the pharmaceutical industry | 27 | 59.2 | 0.08 (**) | 18 | 58.56 | n.s. | |

| Perceived Harmfulness | Vaccination is harmful because ... | ||||||

| ... long-term risks are not known/risk bigger than benefit | 46 | 59.8 | 0.12 (***) | 14 | 59.3 | 0.06 (*) | |

| … new vaccines pose additional risks in the RNA/not controlled enough | 24 | 60.8 | 0.11 (***) | 16 | 60.0 | 0.08 (**) | |

| ... there are doctors who advise against it | 24 | 60.0 | 0.08 (***) | 15 | 60.6 | 0.07 (**) | |

| … a compulsory corona vaccination with prioritisation of certain groups will lead to major socio-political discussions/bad experiences | 34 | 61.0 | 0.15 (***) | 15 | 61.0 | 0.09 (***) | |

| COVID-19’s Impact on Childhood Vaccination | Considering COVID-19, my views on childhood vaccination are: | ||||||

| It is important that my children get the necessary protection | --- | --- | --- | 65 | 57.7 | n.s. | |

| It is important to guarantee heard immunity | --- | --- | --- | 64 | 57.6 | n.s. | |

| I’m worried about the decline of obligatory vaccination due to the pandemic | --- | --- | --- | 41 | 58.6 | 0.06 (*) | |

| General Childhood Vaccination Attitudes | Despite COVID-19, everybody should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination plan | --- | --- | --- | 64 | 57.6 | n.s. |

| How serious would the consequences be for the health of your child if you did not do the mandatory childhood vaccination? (n = 953) | --- | --- | --- | 63 | 58.1 | n.s. | |

| General COVID-19 Vaccination Attitudes | I believe the vaccination can contain the spread of the virus | 71 | 57.34 | n.s. | --- | --- | --- |

| When all the others are vaccinated against the virus, I don’t need to get vaccinated | 10 | 59.37 | n.s. | --- | --- | --- | |

| Predictors of Spirituality (n = 1369) | Correlation R2 = 0.164 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient b | [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| Constant term | 14.572 | [8.891; 20.254] | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.106 | [0.053; 0.159] | <0.001 |

| Gender | 4.604 | [2.722; 6.486] | <0.001 |

| CAM consultation | 5.432 | [3.166; 7.698] | <0.001 |

| Due to the pandemic, I support mandatory childhood vaccination more now | 2.829 | [0.240; 5.417] | 0.032 |

| Due to the pandemic, I support mandatory childhood vaccination less now | n.s. | ||

| Well-being | 1.126 | [1.440; 0.813] | <0.001 |

| Altruism | 0.919 | [0.740; 1.098] | <0.001 |

| Conspiracy thinking | 0.267 | [0.143; 0.410] | <0.001 |

| Predictors of Harmfulness of COVID-19 Vaccination (n = 1369) | Correlation R2 = 0.423 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient b | [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| Constant term | 13.100 | [11.712; 14.488] | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.025 | [−0.038; −0.012] | <0.001 |

| Conspiracy thinking | 0.234 | [0.196; 0.271] | <0.001 |

| Urban residency | n.s. | ||

| Due to the pandemic, I support mandatory childhood vaccination more now | n.s. | ||

| Due to the pandemic, I support mandatory childhood vaccination less now | 3.832 | [3.027; 4.638] | <0.001 |

| CAM consultation | 0.707 | [0.144; 1.271] | 0.014 |

| Better economic situation | n.s. | ||

| Worse economic situation | n.s. | ||

| Don’t know about the economic situation | 1.481 | [0.144; 1.271] | 0.044 |

| Low educational status | n.s. | ||

| Vocational school | n.s. | ||

| University degree | n.s. | ||

| Trust in institutions | −0.214 | [−0.240; −0.188] | <0.001 |

| Trust in vaccination staff | n.s. | ||

| Spirituality | 0.035 | [0.023; 0.047] | <0.001 |

| Predictors | C | c’ | a × b | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.0282 [−0.0424; −0.0142] | −0.031 *** | 0.0029 * | −2.8% |

| Conspiracy thinking | 0.2287 [0.1877; 0.2710] | 0.2179 *** | 0.0108 * | 4.7% |

| CAM consultation | 0.8019 [0.2313; 1.3707] | 0.609 * | 0.1929 ** | 24.1% |

| Support mandatory vaccination less now | 3.4919 *** | |||

| Don’t know about my economic situation | n.s. | |||

| Trust in institutions | −0.2207 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Büssing, A.; Gärtner, T.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Spirituality, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Use of Complementary Medicine in Vaccine Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030413

Barbieri V, Lombardo S, Büssing A, Gärtner T, Piccoliori G, Engl A, Wiedermann CJ. Spirituality, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Use of Complementary Medicine in Vaccine Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030413

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbieri, Verena, Stefano Lombardo, Arndt Büssing, Timon Gärtner, Giuliano Piccoliori, Adolf Engl, and Christian J. Wiedermann. 2025. "Spirituality, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Use of Complementary Medicine in Vaccine Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030413

APA StyleBarbieri, V., Lombardo, S., Büssing, A., Gärtner, T., Piccoliori, G., Engl, A., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2025). Spirituality, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Use of Complementary Medicine in Vaccine Attitudes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northern Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030413