The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Alcohol Use in First Responders: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Direct, Mediating and Moderating Role of Generalized Resistance Resources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, M.A.P.J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglesby, M.E.; Gibby, B.A.; Mathes, B.M.; Short, N.A.; Schmidt, N.B. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms: An Investigation within a Treatment Seeking Trauma-Exposed Sample. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 72, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltell, K.C.; Edalatian Zakeri, S.; Gorka, S.M.; Berenz, E.C. PTSD Symptoms, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Alcohol-Related Outcomes Among Trauma-Exposed College Students. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, H.; Daniels, J. Coping and Tolerance of Uncertainty: Predictors and Mediators of Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, M.G.; Messner, G.R.; Marks, J.B. Intolerance of uncertainty as a factor linking obsessive-compulsive symptoms, health anxiety and concerns about the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2021, 28, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinciotti, C.M.; Riemann, B.C.; Abramowitz, J.S. Intolerance of uncertainty and obsessive-compulsive disorder dimensions. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 81, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venanzi, L.; Dickey, L.; Green, H.; Pegg, S.; Benningfield, M.M.; Bettis, A.H.; Blackford, J.U.; Kujawa, A. Longitudinal predictors of depression, anxiety, and alcohol use following COVID-19-related stress. Stress Health 2022, 38, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Ghisi, M.; Caggiu, I.; Lauriola, M. How is intolerance of uncertainty related to negative affect in individuals with substance use disorders? The role of the inability to control behaviors when experiencing emotional distress. Addict. Behav. 2021, 115, 106785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.L.; Li, M.; Minihan, S.; Songco, A.; Fox, E.; Ladouceur, C.D.; Mewton, L.; Moulds, M.; Pfeifer, J.H.; Van Harmelen, A.-L.; et al. The effect of intolerance of uncertainty on anxiety and depression, and their symptom networks, during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Lee, T.; Hong, Y.; Ahmed, O.; Silva, W.A.D.; Gouin, J.-P. Viral Anxiety Mediates the Influence of Intolerance of Uncertainty on Adherence to Physical Distancing Among Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 839656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, Z.; Tagay, Ö. The relationships between resilience of the adults affected by the covid pandemic in Turkey and COVID-19 fear, meaning in life, life satisfaction, intolerance of uncertainty and hope. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, F. The Fear of COVID-19 Raises the Level of Depression, Anxiety and Stress through the Mediating Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty. Stud. Psychol. 2021, 63, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voitsidis, P.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Holeva, V.; Parlapani, E.; Sereslis, K.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Tsopaneli, N.; Diakogiannis, I. The mediating role of fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 94, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauriola, M.; Carleton, R.N.; Tempesta, D.; Calanna, P.; Socci, V.; Mosca, O.; Salfi, F.; De Gennaro, L.; Ferrara, M. A Correlational Analysis of the Relationships among Intolerance of Uncertainty, Anxiety Sensitivity, Subjective Sleep Quality, and Insomnia Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arditte Hall, K.A.; Arditte, S.J. Threat-Related Interpretation Biases and Intolerance of Uncertainty in Individuals Exposed to Trauma. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2024, 48, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Çağış, Z.G.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Intolerance of Uncertainty, Job Satisfaction and Work Performance in Turkish Healthcare Professionals: Mediating Role of Psychological Capital. Int. J. Public Health 2024, 69, 1607127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A.; Hoffman, J.; Keegan, D.; Kashyap, S.; Argadianti, R.; Tricesaria, D.; Pestalozzi, Z.; Nandyatama, R.; Khakbaz, M.; Nilasari, N.; et al. Intolerance of uncertainty, posttraumatic stress, depression, and fears for the future among displaced refugees. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 94, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauss, K.; Houtsma, C.; Shapiro, M.O.; McDermott, M.J.; Macia, K.S.; Franklin, C.L.; Raines, A.M.; Ferreira, R.J. Anxiety Sensitivity and Intolerance of Uncertainty Among Veterans with Subthreshold Versus Threshold PTSD. Traumatology 2024, 30, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, V.; Passannante, M.; Pierrini, F.; Carpinelli, L.; Moccia, G.; Marinaci, T.; Capunzo, M.; Pironti, C.; Genovese, A.; Savarese, G.; et al. Burnout and Psychological Vulnerability in First Responders: Monitoring Depersonalization and Phobic Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, C.C.; Vujanovic, A.A.; Murphy, J.G.; Rosmarin, D.H. The association between PTSD symptom clusters and religion/spirituality with alcohol use among first responders. J. Psychiatr. Res 2024, 176, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, P.G.; Eisner, Z.J.; Bustos, A.; Hancock, C.J.; Thullah, A.H.; Jayaraman, S.; Raghavendran, K. Cost-Effectiveness of Lay First Responders Addressing Road Traffic Injury in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 270, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.W.; Kruger, L. Mindset as a resilience resource and perceived wellness of first responders in a South African context. Jamba 2022, 14, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Pretorius, T.B. Being Cynical Is Bad for Your Wellbeing: A Structural Equation Model of the Relationship Between Cynicism and Mental Health in First Responders in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, L.; Moodley, I.; Muslim, T.A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of emergency care practitioners in the management of common dental emergencies in the eThekwini District, KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2022, 77, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntatamala, I.; Adams, S. The correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder in ambulance personnel and barriers faced in accessing care for work-related stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, A.; Lesch, M.; Golder, S.; McCambridge, J. Alcohol policy framing in South Africa during the early stages of COVID-19: Using extraordinary times to make an argument for a new normal. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Cocks, B.F.; Manthey, C.; Kendall-Tackett, K.; Kendall-Tackett, K.A. Ambulance Ramping Predicts Poor Mental Health of Paramedics. Psychol. Trauma 2023, 15 (Suppl. S2), S305–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogner, J.; Miller, B.L.; McLean, K. Police Stress, Mental Health, and Resiliency during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 45, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Ashwick, R.; Schlosser, M.; Jones, R.; Rowe, S.; Billings, J. Global prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in police personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryshchuk, L.; Campbell, M.A.; Brunelle, C.; Doyle, J.N.; Nero, J.W. Profiles of Vulnerability to Alcohol Use and Mental Health Concerns in First Responders. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2022, 37, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizar, P.; Puddephatt, J.-A.; Gage, S.H.; Fallon, V.; Goodwin, L. The prevalence of hazardous and harmful alcohol use across trauma-exposed occupations: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 226, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonumwezi, J.L.; Tramutola, D.; Lawrence, J.; Kobezak, H.M.; Lowe, S.R. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, work-related trauma exposure, and substance use in first responders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 237, 109439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1997, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilewicz, M.; Babińska, M.; Gromova, A. High rates of probable PTSD among Ukrainian war refugees: The role of intolerance of uncertainty, loss of control and subsequent discrimination. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2024, 15, 2394296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, H.-A.; O’Donnell, M.L.; Putica, A.; Sadler, N.; Peck, T.; Nursey, J.; Varker, T.; Kearney, L.K. Mental Health Treatment for First Responders: An Assessment of Mental Health Provider Needs. Psychol. Serv. 2024, 21, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, P.T.; McCrillis, A.M.; Smid, G.E.; Nijdam, M.J. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res 2017, 94, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagee, A.; Padmabhanunni, A.; Coetzee, B.; Booysen, D.; Kidd, M. Sense of coherence, social support, satisfaction with life, and resilience as mediators between fear of COVID-19, perceived vulnerability to disease and depression. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2024, 54, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danioni, F.; Barni, D.; Ferrari, L.; Ranieri, S.; Canzi, E.; Iafrate, R.; Lanz, M.; Regalia, C.; Rosnati, R. The enduring role of sense of coherence in facing the pandemic. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Isaacs, S.; Pretorius, T.; Faroa, B. Generalized Resistance Resources in the Time of COVID-19: The Role of Sense of Coherence and Resilience in the Relationship between COVID-19 Fear and Loneliness among Schoolteachers. OBM Neurobiol. 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana, A.; Bauer, G.F.; Meier Magistretti, C.; Sardu, C.; Juvinyà-Canal, D.; Hardy, L.J.; Catz, O.; Tušl, M.; Sagy, S. Order out of chaos: Sense of coherence and the mediating role of coping resources in explaining mental health during COVID-19 in 7 countries. SSM-Ment. Health 2021, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, S.; Pijpker, R.; Polhuis, K. The relationship between individual, social and national coping resources and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-S.; Hasson, F. Resilience, stress, and psychological well-being in nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 90, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Maria, A.; Wörfel, F.; Wolter, C.; Gusy, B.; Rotter, M.; Stark, S.; Kleiber, D.; Renneberg, B. The Role of Job Demands and Job Resources in the Development of Emotional Exhaustion, Depression, and Anxiety Among Police Officers. Police Q. 2018, 21, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Job demands and resources as antecedents of university teachers’ exhaustion, engagement and job satisfaction. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 40, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 4, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T. A Short Hardiness Scale; American Psychological Society Annual Convention: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio; Johnston, M., Wright, S., Weinman, J., Eds.; Nfer-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion, Self-Esteem, and Well-Being. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.F.; De La Fuente, J.R.; Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Cultural Tightness-Looseness: Two Antecedents of Effectuation-Causation: Evidence from South Africa. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil, H.G. To Predict, Or to Control That Is the Question: The Influence of Intolerance of Uncertainty on Entrepreneurial Decision-Making Behaviour. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, T.B.; Padmanabhanunni, A. Validation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 in South Africa: Item Response Theory and Classical Test Theory. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S. Self-compassion mediates the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and athlete burnout among adolescent squash players in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sports Med. 2021, 33, v33i1a11877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Mayer, C.-H.; Vanderheiden, E. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Mental Health Between German and South African Employees: Shame, Self-Compassion, Work Engagement, and Work Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 627851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelinghuys, J.R. General Self–Efficacy as a Moderator Between Stress and Positive Mental Health in an African Context. Master’s Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Mayson, T. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Scale (AUDIT) normative scores for a multiracial sample of Rhodes University residence students. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2010, 22, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor Enterprises. Excess Kurtosis. Available online: https://variation.com/wp-content/distribution_analyzer_help/hs139.htm (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, C.M.; Kenny, D.A.; McClelland, G.H. Estimating and Testing Mediation and Moderation in Within-Subject Designs. Psychol. Methods 2001, 6, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carden, S.W.; Holtzman, N.S.; Strube, M.J. CAHOST: An Excel Workbook for Facilitating the Johnson-Neyman Technique for Two-Way Interactions in Multiple Regression. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.O.; Neyman, J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat. Res. Mem. 1936, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, A.; Roysircar, G.; Rodgers, S. First responder mental healthcare: Evidence-based prevention, postvention, and treatment. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2018, 49, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlearney, A.S.; Gaughan, A.A.; MacEwan, S.R.; Gregory, M.E.; Rush, L.J.; Volney, J.; Panchal, A.R. Pandemic experience of first responders: Fear, frustration, and stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIzana, T.; Adams, S.; Khan, S.; Ntatamala, I. Sociodemographic and work-related factors associated with psychological resilience in South African healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachi, A.; Kavourgia, E.; Bratis, D.; Fytsilis, K.; Papageorgiou, S.M.; Lekka, D.; Sikaras, C.; Tselebis, A. Anger and Aggression in Relation to Psychological Resilience and Alcohol Abuse among Health Professionals during the First Pandemic Wave. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safiye, T.; Gutić, M.; Dubljanin, J.; Stojanović, T.M.; Dubljanin, D.; Kovačević, A.; Zlatanović, M.; Demirović, D.H.; Nenezić, N.; Milidrag, A. Mentalizing, Resilience, and Mental Health Status among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Lyu, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Xia, G.; Zhang, J. Self-efficacy and positive coping mediate the relationship between social support and resilience in patients undergoing lung cancer treatment: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 953491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. The effect of teacher self-efficacy, teacher resilience, and emotion regulation on teacher burnout: A mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1185079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, S. The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty, coping style, resilience, and anxiety during the COVID-19 relapse in freshmen: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1136084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahesh, E.; Ondrejack, L. Intolerance of uncertainty dimensions and alcohol problems: The effects of coping motives and heavy drinking. J. Addict. Offender Couns. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Q.; Xia, M.; An, J. The Relationship Between Self-Control and Self-Efficacy Among Patients With Substance Use Disorders: Resilience and Self-Esteem as Mediators. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Addas, A.; Rehman, E.; Khan, M.N. The Mediating Roles of Self-Compassion and Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Psychological Resilience and Mental Health Among College Teachers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 4119–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Shen, J. Dispositional mindfulness and mental health among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 lockdown: The mediating role of self-compassion and the moderating role of gender. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1072548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrocchi, N.; Ottaviani, C.; Cheli, S.; Matos, M.; Baldi, B.; Basran, J.K.; Gilbert, P.; Nezu, A.M. The Impact of Compassion-Focused Therapy on Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes: Results of a Series of Meta-Analyses. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 31, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelin, K.E.; Perman, G.; Simonds, L.M. Effectiveness of self-compassion-related interventions for reducing self-criticism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2022, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale/Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IU | — | |||||

| 2. Resilience | 0.13 ** | — | ||||

| 3. Hardiness | 0.27 *** | 0.51 *** | — | |||

| 4. Self-efficacy | 0.14 ** | 0.63 *** | 0.63 *** | — | ||

| 5. Self-compassion | 0.35 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.32 *** | — | |

| 6. Alcohol use | 0.09 | −0.17 *** | −0.02 | −0.15 ** | 0.11 * | — |

| Mean | 35.72 | 26.48 | 26.34 | 30.45 | 38.49 | 8.87 |

| SD | 9.51 | 8.02 | 8.37 | 5.93 | 8.14 | 10.01 |

| Skewness | 0.17 | −0.40 | 0.07 | −0.61 | 0.01 | 1.14 |

| Kurtosis | −0.31 | −0.19 | −0.07 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.60 |

| Alpha | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.94 |

| Omega | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.94 |

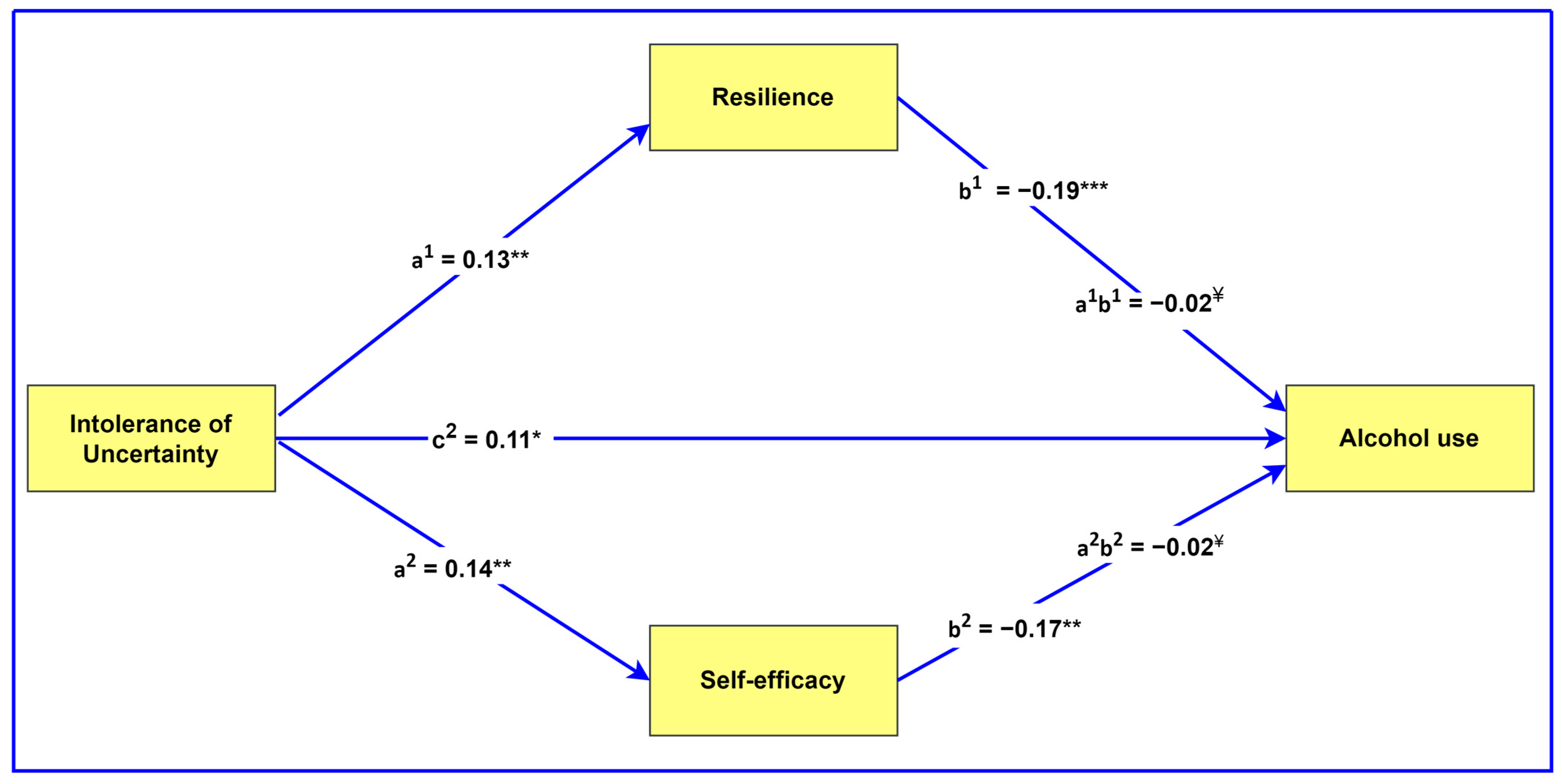

| Effect Type | Effect | B | SE | 95% CI | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | resilience → alcohol use | −0.23 | 0.06 | [−0.35, −0.12] * | −0.19 | <0.001 |

| hardiness → alcohol use | −0.05 | 0.06 | [−0.17, 0.07] | −0.04 | 0.408 | |

| self-efficacy → alcohol use | −0.28 | 0.08 | [−0.44, −0.12] * | −0.17 | 0.001 | |

| self-compassion → alcohol use | 0.11 | 0.06 | [−0.01, 0.24] | 0.09 | 0.072 | |

| Mediating effects | IU → resilience → alcohol use | −0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.05, −0.00] * | −0.02 | — |

| IU → hardiness → alcohol use | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04. 0.02] | −0.01 | — | |

| IU → self-efficacy → alcohol use | −0.02 | 0.01 | [−0.05, −0.00] * | −0.02 | — | |

| IU → self-compassion → alcohol use | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.08] | 0.03 | — | |

| Moderating effects | IU X resilience → alcohol use | 0.00 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.03 | >0.05 |

| IU X hardiness → alcohol use | −0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.01] | −0.04 | 0.417 | |

| IU X self-efficacy → alcohol use | 0.00 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.01 | 0.881 | |

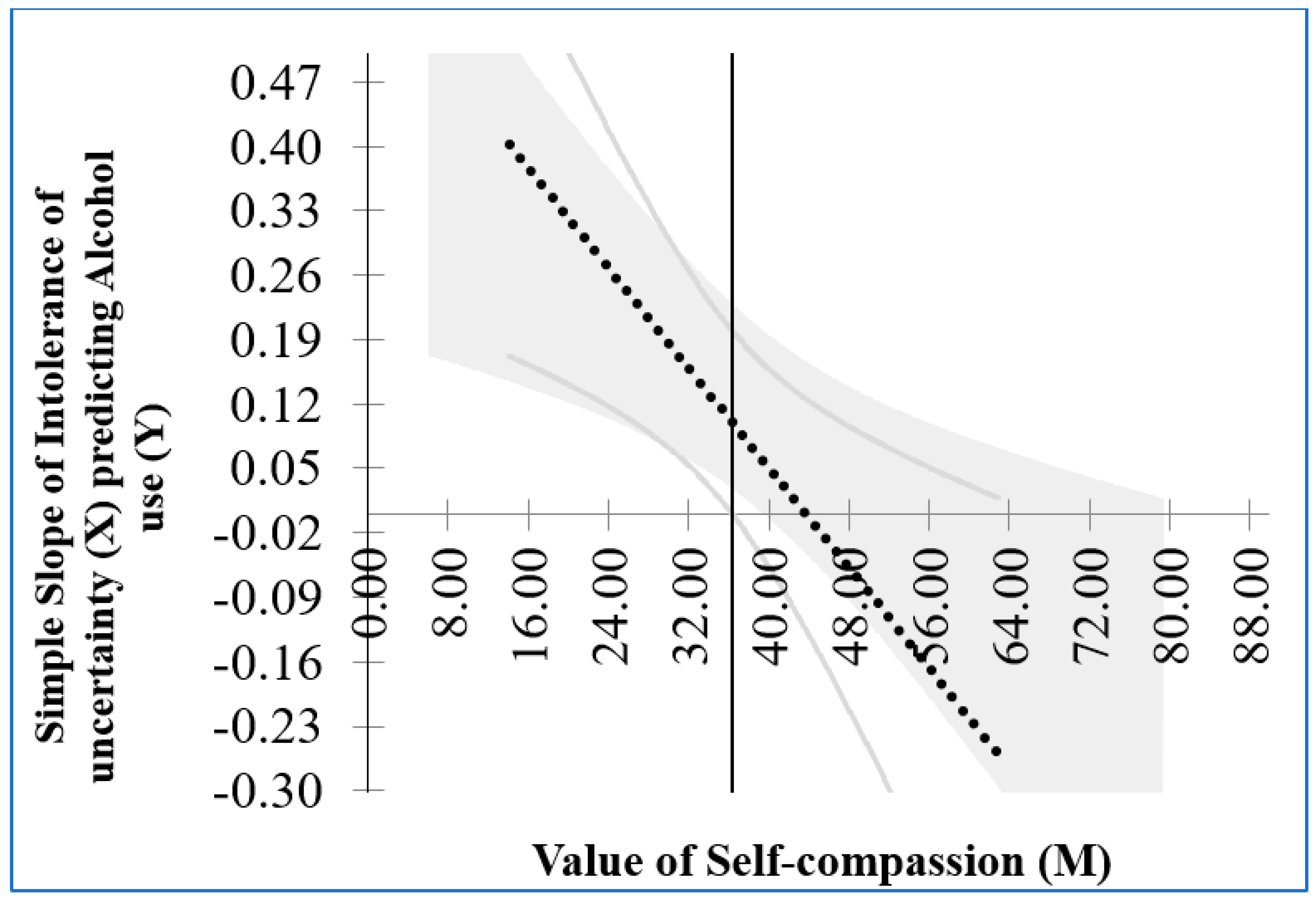

| IU X self-compassion → alcohol use | −0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.02, −0.00] * | −0.11 | 0.013 |

| Self-Compassion | Effect | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 standard deviation below the mean | 0.18 | 0.07 | [0.04, 0.32] | 0.012 |

| Mean | 0.07 | 0.05 | [−0.04, 0.18] | 0.189 |

| 1 standard deviation above the mean | −0.04 | 0.07 | [−0.17, 0.09] | 0.555 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pretorius, T.B.; Padmanabhanunni, A. The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Alcohol Use in First Responders: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Direct, Mediating and Moderating Role of Generalized Resistance Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030383

Pretorius TB, Padmanabhanunni A. The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Alcohol Use in First Responders: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Direct, Mediating and Moderating Role of Generalized Resistance Resources. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030383

Chicago/Turabian StylePretorius, Tyrone B., and Anita Padmanabhanunni. 2025. "The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Alcohol Use in First Responders: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Direct, Mediating and Moderating Role of Generalized Resistance Resources" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030383

APA StylePretorius, T. B., & Padmanabhanunni, A. (2025). The Relationship Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Alcohol Use in First Responders: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Direct, Mediating and Moderating Role of Generalized Resistance Resources. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030383