Validation of the Canadian English and French Versions of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in Quebec Nursing Staff

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

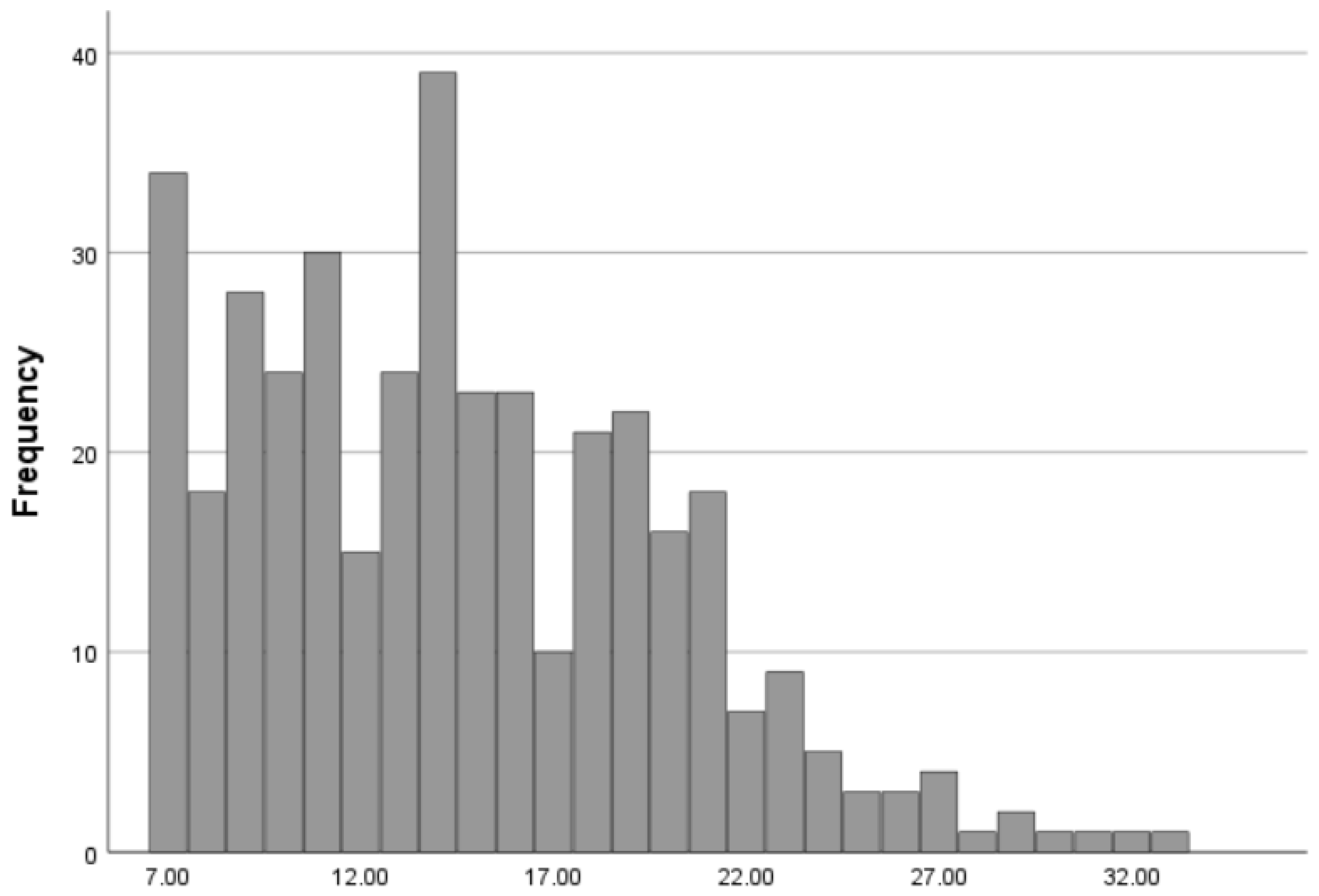

3.1. Description of Study Sample and Scale Scores

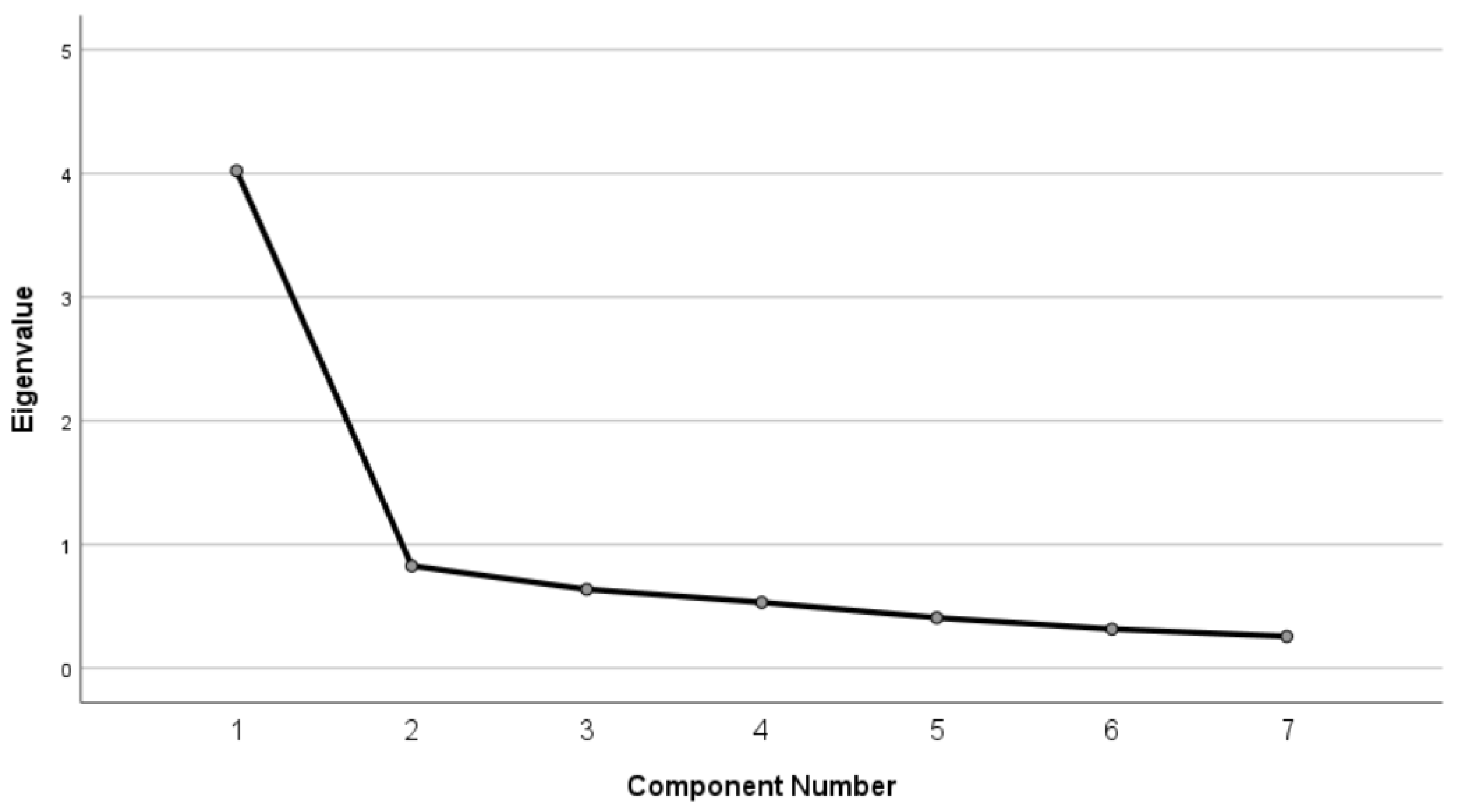

3.2. Structural Validation

3.3. Convergent Validation

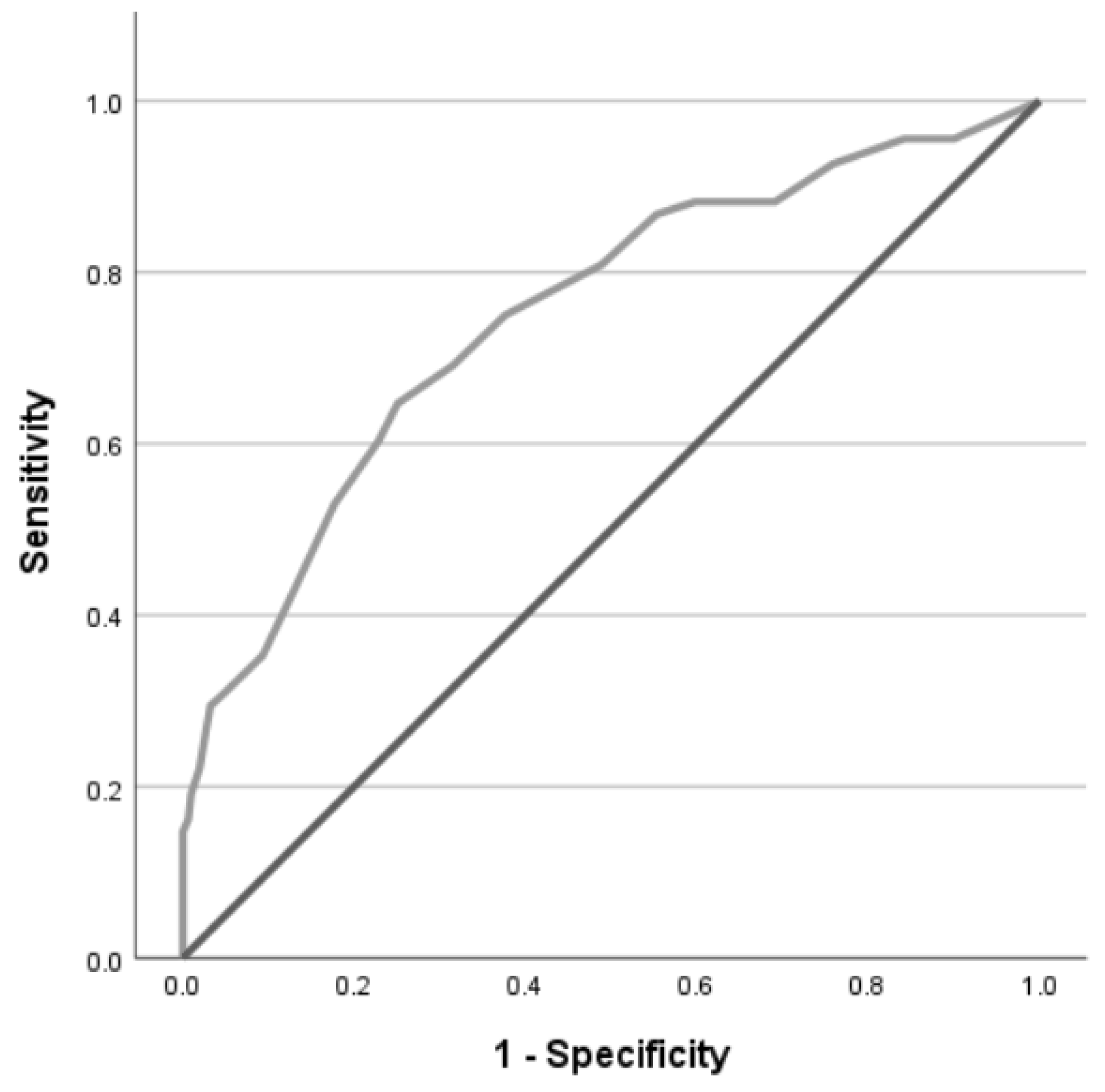

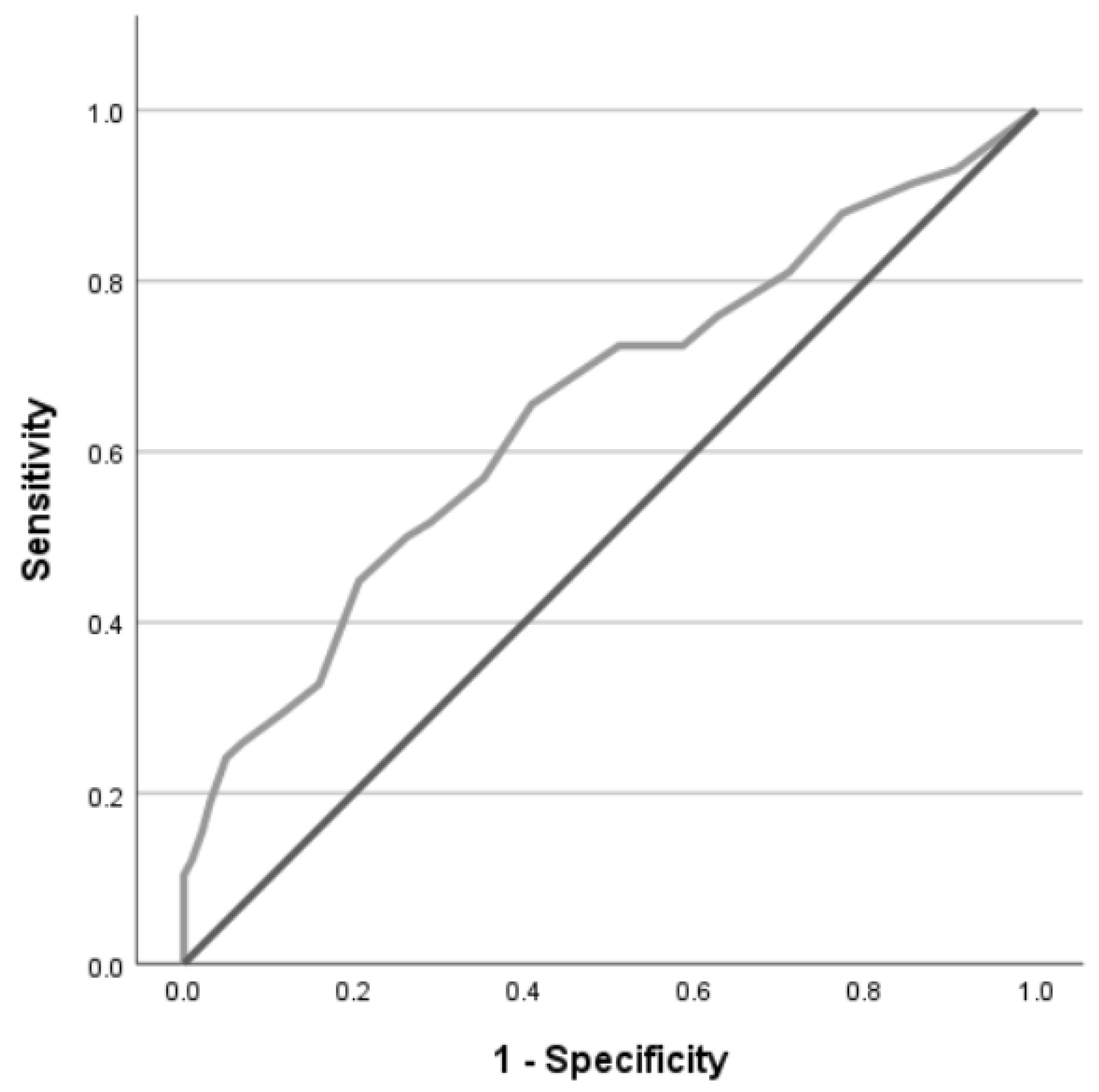

3.4. Criterion Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Canadian French Version | |||||

| Items | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) |

| 1 | 339 | 2.56 (1.09) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.41 (0.13) | −0.56 (0.27) |

| 2 | 337 | 2.56 (1.17) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.19 (0.13) | −1.04 (0.27) |

| 3 | 337 | 1.61 (0.79) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.33 (0.13) | 1.58 (0.27) |

| 4 | 337 | 1.95 (1.10) | 2.00 (2.00) | 1.08 (0.13) | 0.34 (0.27) |

| 5 | 338 | 2.46 (1.19) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.26 (0.13) | −1.12 (0.27) |

| 6 | 338 | 1.51 (0.77) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.59 (0.13) | 2.31 (0.27) |

| 7 | 337 | 1.67 (0.93) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.44 (0.13) | 1.57 (0.27) |

| Overall score | 335 | 14.32 (5.35) | 14.00 (8.00) | 0.67 (0.13) | 0.11 (−0.27) |

| Canadian English Version | |||||

| Items | n | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) |

| 1 | 48 | 2.69 (1.17) | 3.00 (2.00) | 0.23 (0.34) | −0.83 (0.67) |

| 2 | 48 | 2.58 (1.19) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.24 (0.34) | −1.00 (0.67) |

| 3 | 48 | 1.90 (0.88) | 2.00 (1.00) | 1.18 (0.34) | 2.17 (0.67) |

| 4 | 48 | 2.17 (1.14) | 2.00 (2.00) | 1.02 (0.34) | 0.56 (0.67) |

| 5 | 48 | 2.88 (1.18) | 3.00 (2.00) | −0.16 (0.34) | −1.17 (0.67) |

| 6 | 48 | 2.00 (0.97) | 2.00 (1.00) | 1.03 (0.34) | 0.99 (0.67) |

| 7 | 48 | 1.98 (0.96) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.50 (0.34) | −0.87 (0.67) |

| Overall score | 48 | 16.19 (5.63) | 15.50 (7.50) | 0.41 (0.34) | −0.07 (0.67) |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Items | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Items | 1 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2 | 0.56 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.39 | 0.50 1 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4 | 0.58 | 0.48 1 | 0.55 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5 | 0.44 2 | 0.61 1 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 1.00 | |||

| 6 | 0.38 2 | 0.43 1 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 1.00 | ||

| 7 | 0.44 | 0.48 3 | 0.55 1 | 0.55 1 | 0.49 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |

| Total | 0.74 3 | 0.80 3 | 0.71 3 | 0.76 3 | 0.78 3 | 0.71 3 | 0.75 3 | |

Appendix D

References

- World Health Organization. WHO-Convened Global Study of Origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutambudzi, M.; Niedwiedz, C.; Macdonald, E.B.; Leyland, A.; Mair, F.; Anderson, J.; Celis-Morales, C.; Cleland, J.; Forbes, J.; Gill, J.; et al. Occupation and risk of severe COVID-19: Prospective cohort study of 120 075 UK Biobank participants. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 78, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Goetz, C.M.; Sudan, S.; Arble, E.; Janisse, J.; Arnetz, B.B. Personal Protective Equipment and Mental Health Symptoms Among Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Norful, A.A.; Travers, J.; Aliyu, S. Nursing perspectives on care delivery during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2020, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Hu, K.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gou, X.; Li, X. A qualitative study of the vocational and psychological perceptions and issues of transdisciplinary nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak. Aging 2020, 12, 12479–12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehdar, N.; Kamran, A.; Toulabi, T.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancani, L.; Marinucci, M.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Forced Social Isolation and Mental Health: A Study on 1006 Italians Under COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsir, Z.; Koc, H.; Seki, T.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullone, E. The development of normal fear: A century of research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, L.M.; Liberzon, I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, R.; Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Basavarachar, V.; Dakshinamoorthy, R. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunitri, N.; Chu, H.; Kang, X.L.; Jen, H.J.; Pien, L.C.; Tsai, H.T.; Kamil, A.R.; Chou, K.R. Global prevalence and associated risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 126, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Gong, Y.M.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.K.; Tian, S.S.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, A.Y.; Su, S.Z.; Liu, X.X.; et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4982–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, A.; Shinkawa, H.; Kubo, T. Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Japanese Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale Among Adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Lin, C.Y.; Ullah, I.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. Item Response Theory Analysis of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S): A Systematic Review. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, F.; Bakkar, B.; Khadem Alsrouji, S.; Abbas, E.; Najjar, A.; Marrawi, M.; Latifeh, Y. Fear among Syrians: A Proposed Cutoff Score for the Arabic Fear of COVID-19 Scale. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Do, B.N.; Pham, K.M.; Kim, G.B.; Dam, H.T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, Y.H.; Sorensen, K.; Pleasant, A.; et al. Fear of COVID-19 Scale—Associations of Its Scores with Health Literacy and Health-Related Behaviors among Medical Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikopoulou, V.A.; Holeva, V.; Parlapani, E.; Karamouzi, P.; Voitsidis, P.; Porfyri, G.N.; Blekas, A.; Papigkioti, K.; Patsiala, S.; Diakogiannis, I. Mental Health Screening for COVID-19: A Proposed Cutoff Score for the Greek Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Ahmed, O.; Silva, W.A.D.; Park, C.H.K.; Yoo, S.; Chung, S. Applicability and Psychometric Comparison of the General-Population Viral Anxiety Rating Scales among Healthcare Workers in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Mu, W.; Jing, W.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale for Chinese University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, D.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, H.; Zhang, F.; Xia, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. The Relationship Between Personality Traits and Clinical Decision-Making, Anxiety and Stress Among Intern Nursing Students During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Kim, J.S. Nursing stress factors affecting turnover intention among hospital nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De los Santos, J.A.A.; Labrague, L.J. The impact of fear of COVID-19 on job stress, and turnover intentions of frontline nurses in the community: A cross-sectional study in the Philippines. Traumatology 2021, 27, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gélinas, C.; Maheu, C.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Richard-Lalonde, M.; Gallani, M.C.; Gosselin, É.; Hébert, M.; Tchouaket Nguemeleu, E.; Côté, J. Translation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale into French-Canadian and English-Canadian and Validation in the Nursing Staff of Quebec. Sci. Nurs. Health Pract. 2021, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvernement du Québec Pandémie de la COVID-19—Le gouvernement du Québec présente le bilan de la dernière journée. Available online: https://www.quebec.ca/nouvelles/actualites/details/pandemie-de-la-covid-19-le-gouvernement-du-quebec-presente-le-bilan-de-la-derniere-journee-33059 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec Données de vaccination contre la COVID-19 au Québec. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/vaccination (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec Données COVID-19 au Québec. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Évolution de la couverture vaccinale contre la COVID-19 au Québec selon le nombre de doses, le groupe d’âge, le groupe prioritaire et la date de vaccination; Institut national de santé publique du Québec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec Ligne du temps COVID-19 au Québec. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/ligne-du-temps (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Price, M.; Szafranski, D.D.; van Stolk-Cooke, K.; Gros, D.F. Investigation of abbreviated 4 and 8 item versions of the PTSD Checklist 5. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 239, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.A.; Lagarde, S.; Barkate, G.; Dufournet, B.; Besancon, C.; Trebuchon-Da Fonseca, A.; Gavaret, M.; Bartolomei, F.; Bonini, F.; McGonigal, A. Rapid detection of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in epilepsy: Validation of the GAD-7 as a complementary tool to the NDDI-E in a French sample. Epilepsy Behav. 2016, 57 (Pt A), 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, J.; Vilagut, G.; Mortier, P.; Ferrer, M.; Alayo, I.; Aragon-Pena, A.; Aragones, E.; Campos, M.; Cura-Gonzalez, I.D.; Emparanza, J.I.; et al. Mental health impact of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers: A large cross-sectional survey. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2021, 14, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Gelinas, C.; Aube, T.; Tchouaket, E.; Tremblay, D.; Gagnon, M.P.; Cote, J. Influence of caring for COVID-19 patients on nurse’s turnover, work satisfaction and quality of care. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cote, J.; Aita, M.; Chouinard, M.C.; Houle, J.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Lessard, L.; Rouleau, G.; Gelinas, C. Psychological distress, depression symptoms and fatigue among Quebec nursing staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1744–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Lima, K.; Loureiro, S.R.; Bolsoni, L.M.; Apolinario da Silva, T.D.; Osorio, F.L. Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of a Brazilian version of the PCL-5 (complete and abbreviated versions). Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1581020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D.; McMillan, D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.E.; Bachmann, L.M.; Jaeschke, R. A readers’ guide to the interpretation of diagnostic test properties: Clinical example of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2003, 29, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Reliability. In Health Measurement Scales—A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 159–199. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resick, P.A.; Miller, M.W. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Anxiety or traumatic stress disorder? J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korem, N.; Duek, O.; Ben-Zion, Z.; Kaczkurkin, A.N.; Lissek, S.; Orederu, T.; Schiller, D.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Levy, I. Emotional numbing in PTSD is associated with lower amygdala reactivity to pain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ma, Y.; Zou, H. Enhanced Youden’s index with net benefit: A feasible approach for optimal-threshold determination in shared decision making. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2020, 26, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Ghanei Gheshlagh, R.; Dalvand, S.; Saedmoucheshi, S.; Li, Q. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Fear of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Ohayon, M.M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Fear of COVID-19 and its association with mental health-related factors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attieh, R.; Koffi, K.; Toure, M.; Parr-Labbe, E.; Pakpour, A.H.; Poder, T.G. Validation of the Canadian French version of the fear of COVID-19 scale in the general population of Quebec. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e32550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, S.E.; Keliat, B.A. Interventions Addressing Nurses’ Psychological Well-being during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Acta Medica Philipp. 2024, 58, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.W.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y. Interventions to reduce burnout and improve the mental health of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials with meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 33, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreta-Herrera, R.; Lopez-Calle, C.; Caycho-Rodriguez, T.; Cabezas Guerra, C.; Gallegos, M.; Cervigni, M.; Martino, P.; Bares, I.; Calandra, M. Is it possible to find a bifactor structure in the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S)? Psychometric evidence in an Ecuadorian sample. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Irshad, M.; Bartels, J. The Interactive Effect of COVID-19 Risk and Hospital Measures on Turnover Intentions of Healthcare Workers: A Time-Lagged Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, M.; Roy, J. Gestion des équipements de protection dans le réseau québécois de la santé: Chronologie des événements, constats et recommandations; Centre sur la productivité et la prospérité—Fondation Walter J. Somers; HEC Montréa: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.; Hosseini, Z. Répercussions de la COVID-19 sur les établissements de soins infirmiers et les résidences pour aînés au Canada en 2021; Statistique Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.N.; Houck, J.R.; Hammert, W.C. A Comparison of PROMIS UE Versus PF: Correlation to PROMIS PI and Depression, Ceiling and Floor Effects, and Time to Completion. J. Hand Surg. 2019, 44, 901.e1–901.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marleau, D.; Loupias, A. Rapport statistique sur l’effectif infirmier et la relève infirmière du Québec 2020–2021; Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Items | n | Mean (SD) | Median (Q25–Q75) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I am very afraid of COVID-19 | 387 | 2.57 (1.10) | 2.00 (2.00–3.00) | 0.39 (0.12) | −0.60 (0.25) |

| 2. It makes me uncomfortable to think about COVID-19 | 385 | 2.56 (1.17) | 2.00 (2.00–4.00) | 0.19 (0.12) | −1.03 (0.25) |

| 3. My hands become clammy when I think about COVID-19 | 385 | 1.64 (0.81) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.65 (0.25) |

| 4. I am afraid of losing my life because of COVID-19 | 385 | 1.97 (1.11) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 1.06 (0.12) | 0.34 (0.25) |

| 5. I become nervous or anxious when watching news and stories about COVID-19 on social media | 386 | 2.52 (1.19) | 2.00 (1.00–4.00) | 0.20 (0.12) | −1.16 (0.25) |

| 6. I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting COVID-19 | 386 | 1.57 (0.81) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.50 (0.12) | 2.08 (0.25) |

| 7. My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting COVID-19 | 385 | 1.71 (0.94) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.30 (0.12) | 1.08 (0.25) |

| Total score | 383 | 14.55 (5.42) | 14.00 (10.00–18.00) | 0.64 (0.13) | 0.04 (0.25) |

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumul. % | Total | % of Variance | Cumul. % | |

| 1 | 4.02 | 57.5 | 57.5 | 3.52 | 50.3 | 50.3 |

| 2 | 0.83 | 11.8 | 69.2 | |||

| 3 | 0.64 | 9.1 | 78.3 | |||

| 4 | 0.53 | 7.6 | 86.0 | |||

| 5 | 0.41 | 5.9 | 91.8 | |||

| 6 | 0.31 | 4.5 | 96.3 | |||

| 7 | 0.26 | 3.7 | 100.0 | |||

| To Detect High Traumatic Stress 1 | To Detect Moderate Anxiety 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden’s Index |

| 10 | 92.6% | 24.1% | 0.17 | 87.9% | 22.7% | 0.11 |

| 11 | 88.2% | 30.9% | 0.19 | 81.0% | 29.0% | 0.10 |

| 12 | 88.2% | 40.2% | 0.28 | 75.9% | 37.4% | 0.13 |

| 13 | 86.8% | 44.7% | 0.32 | 72.4% | 41.4% | 0.14 |

| 14 | 80.9% | 51.1% | 0.32 | 72.4% | 48.9% | 0.21 |

| 15 | 75.0% | 62.4% | 0.37 | 65.5% | 59.2% | 0.25 |

| 16 | 69.1% | 68.5% | 0.38 | 56.9% | 64.8% | 0.22 |

| 17 | 64.7% | 74.9% | 0.40 | 51.7% | 71.0% | 0.23 |

| 18 | 60.3% | 77.2% | 0.38 | 50.0% | 73.8% | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gélinas, C.; Maheu-Cadotte, M.-A.; Di Nardo, É.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M.; Gallani, M.C.; Gosselin, É.; Maheu, C.; Lambert, S.D.; Richard-Lalonde, M.; Tchouaket Nguemeleu, E.; et al. Validation of the Canadian English and French Versions of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in Quebec Nursing Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020297

Gélinas C, Maheu-Cadotte M-A, Di Nardo É, Lavoie-Tremblay M, Gallani MC, Gosselin É, Maheu C, Lambert SD, Richard-Lalonde M, Tchouaket Nguemeleu E, et al. Validation of the Canadian English and French Versions of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in Quebec Nursing Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020297

Chicago/Turabian StyleGélinas, Céline, Marc-André Maheu-Cadotte, Élisabeth Di Nardo, Mélanie Lavoie-Tremblay, Maria Cecilia Gallani, Émilie Gosselin, Christine Maheu, Sylvie D. Lambert, Melissa Richard-Lalonde, Eric Tchouaket Nguemeleu, and et al. 2025. "Validation of the Canadian English and French Versions of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in Quebec Nursing Staff" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020297

APA StyleGélinas, C., Maheu-Cadotte, M.-A., Di Nardo, É., Lavoie-Tremblay, M., Gallani, M. C., Gosselin, É., Maheu, C., Lambert, S. D., Richard-Lalonde, M., Tchouaket Nguemeleu, E., & Côté, J. (2025). Validation of the Canadian English and French Versions of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale in Quebec Nursing Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020297