Effect of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycemic Patterns of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Analysis as a Function of Different Therapeutic Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Medical Data

2.3. Meteorological Data

3. Results

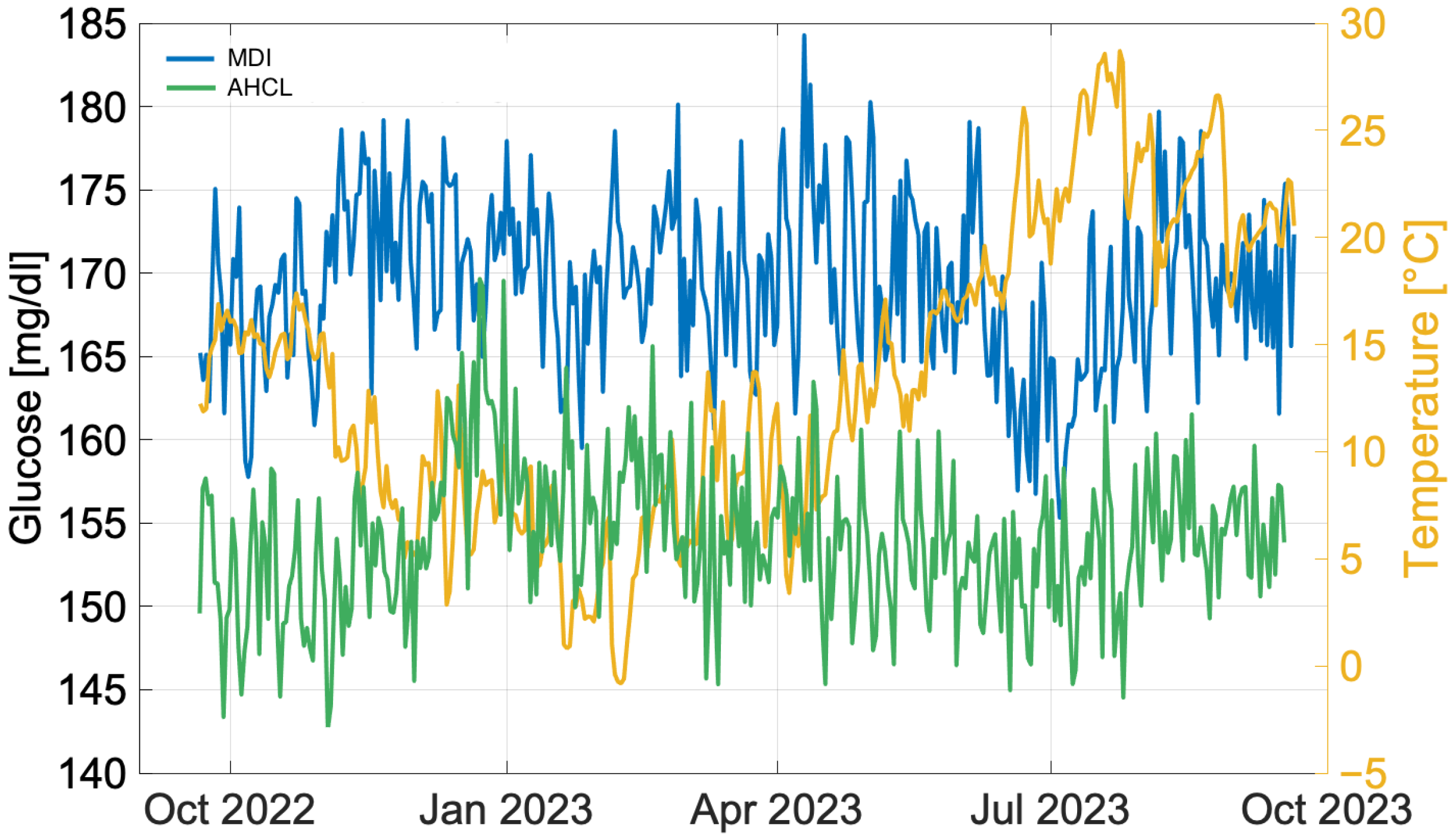

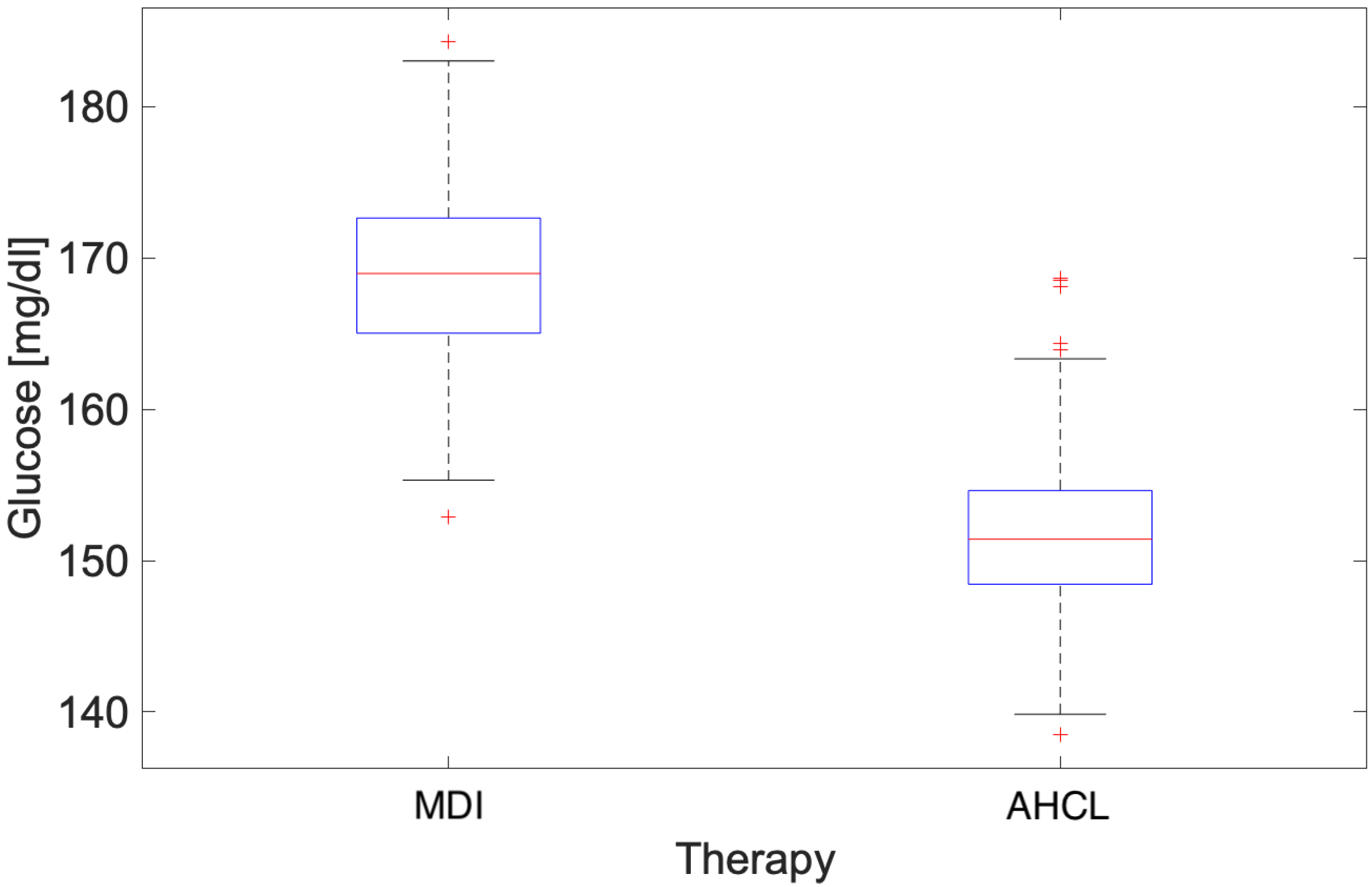

3.1. Annual Analysis

- Number of days the sensor was worn (recommended ≥14 days)

- CGM utilization rate (recommended >70%)

- Average blood glucose

- Estimated glycated haemoglobin

- Glycaemic variability (target CV ≤ 36%)

- TAR (>250 mg/dL) [Level 2]: <5%

- TAR (181–250 mg/dL) [Level 1]: <25%

- TIR (70–180 mg/dL): >70%

- TBR (54–69 mg/dL) [Level 1]: <4%

- TBR (<54 mg/dL) [Level 2]: <1%

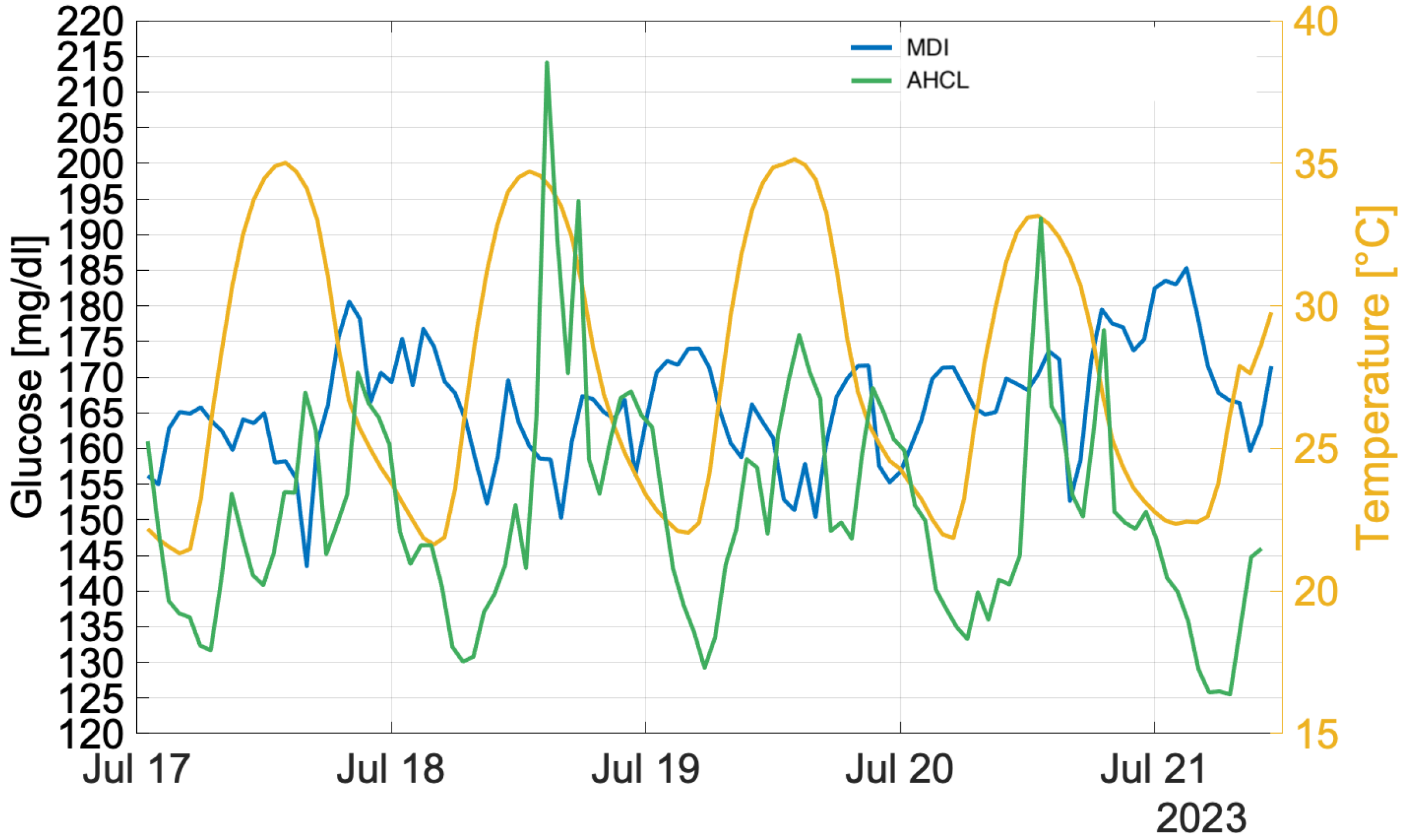

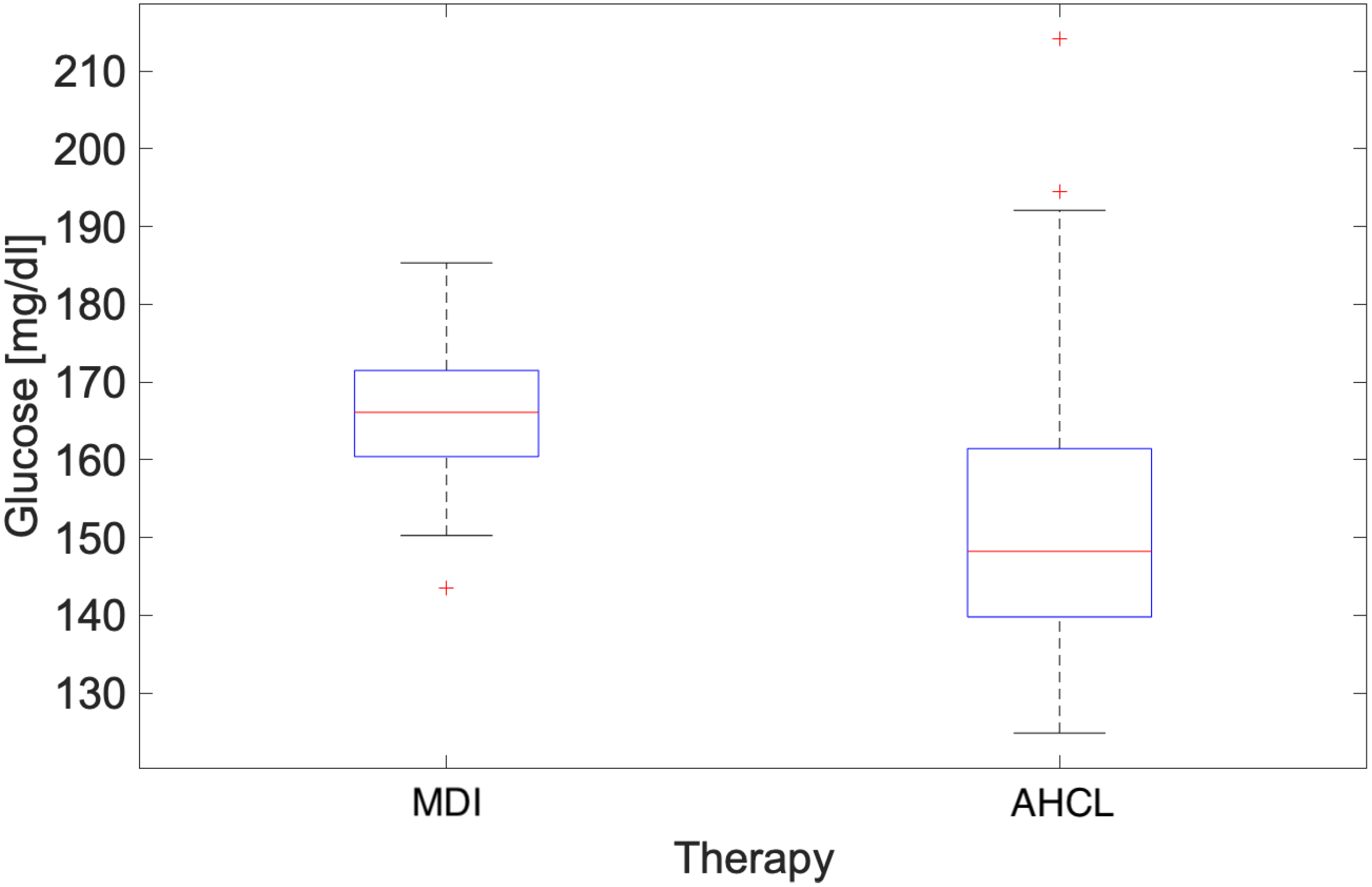

3.2. Heatwave Analysis

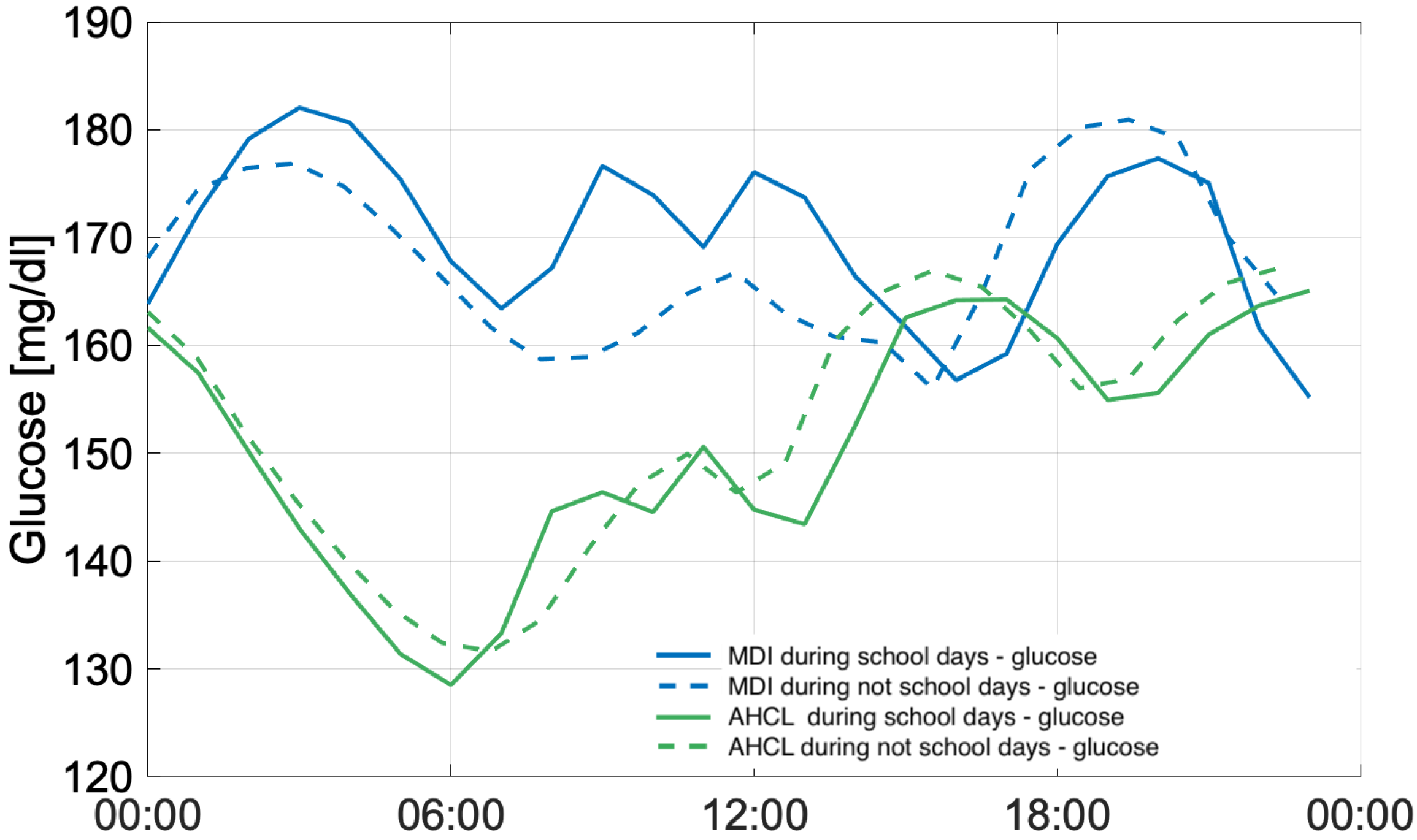

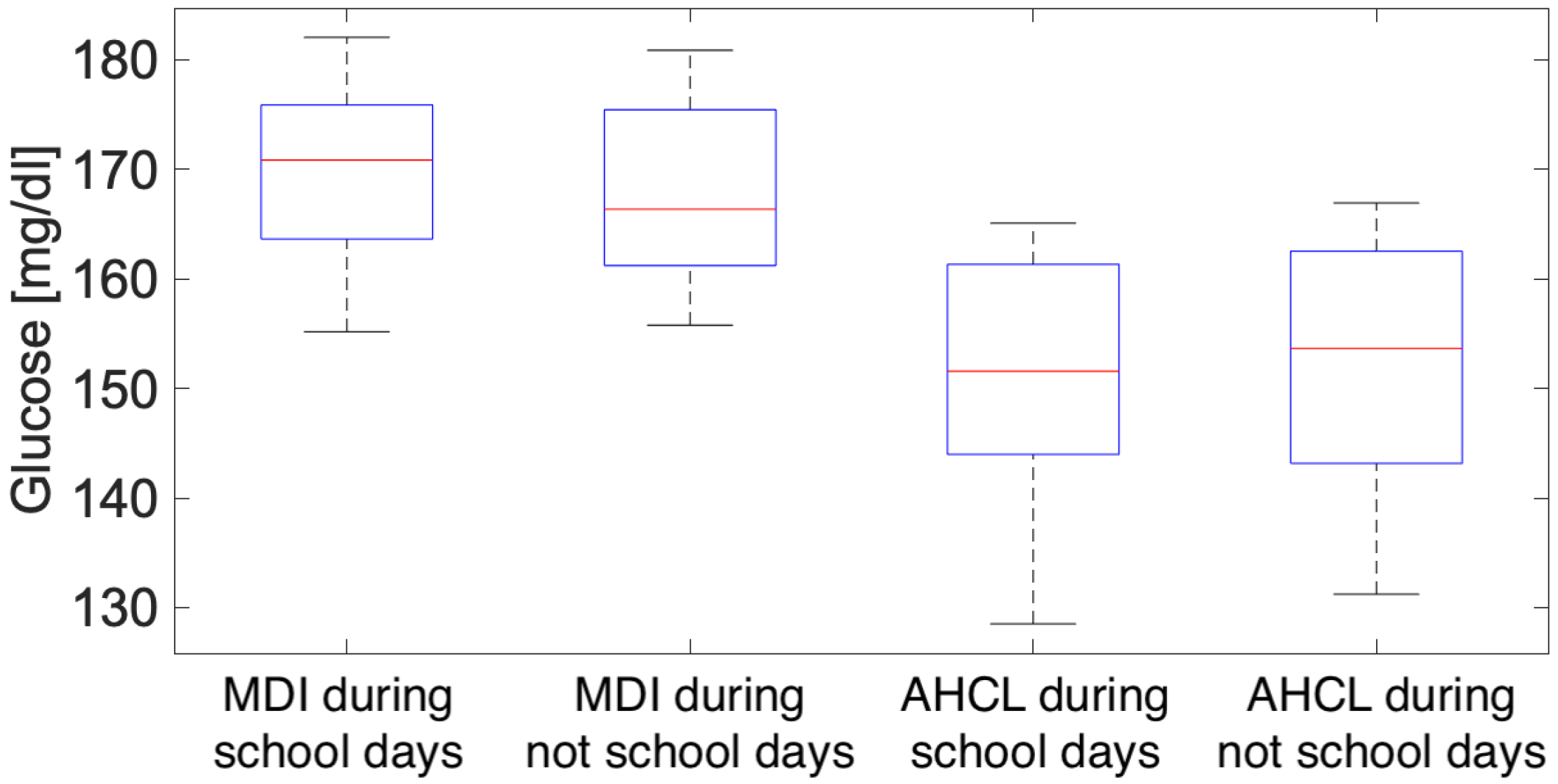

3.3. Working Days and Public Holidays Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Annual Analysis

4.2. Heatwave Analysis

4.3. Working Days and Public Holidays Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ng, S.M.; Wright, N.P.; Yardley, D.; Campbell, F.; Randell, T.; Trevelyan, N.; Ghatak, A.; Hindmarsh, P.C. Long-term assessment of the NHS hybrid closed-loop real-world study on glycaemic outcomes, time-in-range, and quality of life in children and young people with type 1 diabetes. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.M.; Wright, N.P.; Yardley, D.; Campbell, F.; Randell, T.; Trevelyan, N.; Ghatak, A.; Hindmarsh, P.C. Real world use of hybrid-closed loop in children and young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus—A National Health Service pilot initiative in England. Diabet. Med. 2023, 40, e15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchiaretta, P.; Tumini, S.; Mascitelli, A.; Sacrini, L.; Saltarelli, M.A.; Carabotta, M.; Osmelli, J.; Di Carlo, P.; Aruffo, E. The Impact of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycaemic Patterns in Children and Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Climate 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumini, S.; Fioretti, E.; Rossi, I.; Cipriano, P.; Franchini, S.; Guidone, P.I.; Petrosino, M.I.; Saggino, A.; Tommasi, M.; Picconi, L.; et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents: Validation of the Italian version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Children and for Parents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, J.R.; Hood, K.K.; Delamater, A.; Shroff Pendley, J.; Rohan, J.M.; Reeves, G.; Dolan, L.; Drotar, D. Changes in treatment adherence and glycemic control during the transition to adolescence in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, M.; Gajewska, K.A.; Goethals, E.R.; McDarby, V.; Zhao, X.; Hapunda, G.; Delamater, A.M.; DiMeglio, L.A. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Psychological care of children, adolescents and young adults with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Xu, J.; Lin, Z. Association between eHealth literacy, diabetic behavior rating, and burden among caregivers of children with type 1 diabetes: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2023, 73, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovc, K.; Battelino, T.; Beck, R.W.; Sibayan, J.; Bailey, R.J.; Calhoun, P.; Turcotte, C.; Weinzimer, S.; Smigoc Schweiger, D.; Nimri, R.; et al. Impact of temporary glycemic target use in the hybrid and advanced hybrid closed-loop systems. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022, 24, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.K.; Passanisi, S.; Von Dem Berge, T.; Chobot, A.; Elbarbary, N.S.; Pelicand, J.; Giraudo, F.S.; Mentink, R.; Levy-Khademi, F.; Creo, A.L.; et al. SKIN-PEDIC: A Worldwide Assessment of Skin Problems in Children and Adolescents Using Diabetes Devices. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olinder, A.L.; DeAbreu, M.; Greene, S.; Haugstvedt, A.; Lange, K.; Majaliwa, E.S.; Pais, V.; Pelicand, J.; Town, M.; Mahmud, F.H. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Diabetes education in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.R.; Barnett, A.G.; Connell, D.; Tong, S. Ambient Temperature and Cardiorespiratory Morbidity. Epidemiology 2012, 23, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicci, K.R.; Maltby, A.; Clemens, K.K.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Gunz, A.C.; Lavigne, E.; Wilk, P. High Temperatures and Cardiovascular-Related Morbidity: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.L.; Chang, H.H.; Chen, H.F.; Ku, L.J.E.; Chang, Y.H.; Shen, H.N.; Li, C.Y. Inverse relationship between ambient temperature and admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: A 14-year time-series analysis. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhao, Q.; Coelho, M.S.; Saldiva, P.H.; Zoungas, S.; Huxley, R.R.; Abramson, M.J.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Association between Heat Exposure and Hospitalization for Diabetes in Brazil during 2000–2015: A Nationwide Case-Crossover Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 117005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamura, K.; Nawa, N.; Nishimura, H.; Fushimi, K.; Fujiwara, T. Association between heat exposure and hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, and hypoglycemia in Japan. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yin, P.; Zhou, M.; Ou, C.Q.; Guo, Y.; Gasparrini, A.; Liu, Y.; Yue, Y.; Gu, S.; Sang, S.; et al. Cardiovascular mortality risk attributable to ambient temperature in China. Heart 2015, 101, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Nie, Y.; Ke, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; You, J.; Kang, F.; Bai, Y.; et al. A study of temperature variability on admissions and deaths for cardiovascular diseases in Northwestern China. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogar, K.; Brensinger, C.M.; Hennessy, S.; Flory, J.H.; Bell, M.L.; Shi, C.; Bilker, W.B.; Leonard, C.E. Climate Change and Ambient Temperature Extremes: Association with Serious Hypoglycemia, Diabetic Ketoacidosis, and Sudden Cardiac Arrest/Ventricular Arrhythmia in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, e171–e173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, M.; Liu, D.L.; Tong, S.; Xu, Z.; Li, M.; Tong, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, J. Mortality burden of diabetes attributable to high temperature and heatwave under climate change scenarios in China. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. The effect of the heatwave on the morbidity and mortality of diabetes patients; a meta-analysis for the era of the climate crisis. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A.; Guo, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Lavigne, E.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.; Tobias, A.; Tong, S.; Rocklöv, J.; Forsberg, B.; et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: A multicountry observational study. Lancet 2015, 386, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzinger, S.; Biester, T.; Siegel, E.; Schneider, A.; Schöttler, H.; Placzek, K.; Klinkert, C.; Heidtmann, B.; Ziegler, J.; Holl, R. The impact of daily mean air temperature on the proportion of time in hypoglycemia in 2,582 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes—Is this association clinically relevant? Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianowska, B.; Fendler, W.; Szadkowska, A.; Baranowska, A.; Grzelak-Agaciak, E.; Sadon, J.; Keenan, H.; Mlynarski, W. HbA1c levels in schoolchildren with type 1 diabetes are seasonally variable and dependent on weather conditions. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogen, F.; Rodriguez, H.; March, C.A.; Muñoz, C.E.; McManemin, J.; Pellizzari, M.; Rodriguez, J.; Wyckoff, L.; Yatvin, A.L.; Atkinson, T.; et al. Diabetes care in the school setting: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 2050–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corathers, S.D.; DeSalvo, D.J. Therapeutic inertia in pediatric diabetes: Challenges to and strategies for overcoming acceptance of the status quo. Diabetes Spectr. 2020, 33, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, W.H.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, X.; Weng, J.; Luo, S. 690-P: Deterioration in Glycemic Control on School Days among School-Aged Children with Type 1 Diabetes: A Continuous Glucose Monitoring–Based Study. Diabetes 2022, 71, 690-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.I.; Doulla, M.; Seabrook, J.A.; Yau, L.; Hamilton, N.; Salvadori, M.I.; Dworatzek, P.D. Impact of the Balanced School Day on Glycemic Control in Children with Type 1 Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2017, 41, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.; Hovorka, R. Closed-loop insulin delivery: Update on the state of the field and emerging technologies. Expert Rev. Med Devices 2022, 19, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Amiel, S.A.; Beck, R.; Biester, T.; Bosi, E.; Buckingham, B.A.; Cefalu, W.T.; Close, K.L.; et al. Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, C. Heat Stress and the European Heatwave of 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/about/media-centre/science-blog/2023/heat-stress-and-european-heatwave-2023 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Copernicus. European Summer 2023: A Season of Contrasting Extremes. 2023. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/european-summer-2023-season-contrasting-extremes (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Copernicus. The European Heatwave of July 2023 in a Longer-Term Context. 2023. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/european-heatwave-july-2023-longer-term-context (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Fiorillo, E.; Brilli, L.; Carotenuto, F.; Cremonini, L.; Gioli, B.; Giordano, T.; Nardino, M. Diurnal Outdoor Thermal Comfort Mapping through Envi-Met Simulations, Remotely Sensed and In Situ Measurements. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, S.H.; Sapir, T. Methods for insulin delivery and glucose monitoring in diabetes: Summary of a comparative effectiveness review. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2012, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenstal, R.M.; Ahmann, A.J.; Bailey, T.; Beck, R.W.; Bissen, J.; Buckingham, B.; Deeb, L.; Dolin, R.H.; Garg, S.K.; Goland, R.; et al. Recommendations for standardizing glucose reporting and analysis to optimize clinical decision making in diabetes: The Ambulatory Glucose Profile. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.S.; Sun, S.; Weinberger, K.R.; Spangler, K.R.; Sheffield, P.E.; Wellenius, G.A. Warm Season and Emergency Department Visits to U.S. Children’s Hospitals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R.J.; Aoyagi, Y. Seasonal variations in physical activity and implications for human health. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 107, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bock, M.; Agwu, J.C.; Deabreu, M.; Dovc, K.; Maahs, D.M.; Marcovecchio, M.L.; Mahmud, F.H.; Nóvoa-Medina, Y.; Priyambada, L.; Smart, C.E.; et al. International society for pediatric and adolescent diabetes clinical practice consensus guidelines 2024: Glycemic targets. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2025, 97, 546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Biester, T.; Berget, C.; Boughton, C.; Cudizio, L.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Hilliard, M.E.; Reddy, L.; Sap Ngo Um, S.; Schoelwer, M.; Sherr, J.L.; et al. International society for pediatric and adolescent diabetes clinical practice consensus guidelines 2024: Diabetes technologies–insulin delivery. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2025, 97, 636–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karges, B.; Rosenbauer, J.; Stahl-Pehe, A.; Flury, M.; Biester, T.; Tauschmann, M.; Lilienthal, E.; Hamann, J.; Galler, A.; Holl, R.W. Hybrid closed-loop insulin therapy and risk of severe hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in young people (aged 2–20 years) with type 1 diabetes: A population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, W.; Chen, L.; Luo, F.; Chen, T.; Sun, C. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentrations among children and adolescents with diabetes in Middle-and low-income countries, 2010–2019: A Retrospective Chart Review and systematic review of literature. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 651589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, G.; Allen, J.M.; Hartnell, S.; Wilinska, M.E.; Tauschmann, M.; Boughton, C.; Campbell, F.; Denvir, L.; Trevelyan, N.; Wadwa, P.; et al. Assessing the efficacy, safety and utility of 6-month day-and-night automated closed-loop insulin delivery under free-living conditions compared with insulin pump therapy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: An open-label, multicentre, multinational, single-period, randomised, parallel group study protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027856. [Google Scholar]

- Shubrook, J.H.; Brannan, G.D.; Wapner, A.; Klein, G.; Schwartz, F.L. Time needed for diabetes self-care: Nationwide survey of certified diabetes educators. Diabetes Spectr. 2018, 31, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Habeeb, Z.; Bhatia, V.; Dabadghao, P. School-time hyperglycemia and prolonged night-time hypoglycemia on continuous glucose monitoring in children with type 1 diabetes. Indian Pediatr. 2024, 61, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, C.A.; Nanni, M.; Lutz, J.; Kavanaugh, M.; Jeong, K.; Siminerio, L.M.; Rothenberger, S.; Miller, E.; Libman, I.M. Comparisons of School-Day Glycemia in Different Settings for Children with Type 1 Diabetes Using Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Pediatr. Diabetes 2023, 2023, 8176606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hayek, A.; Alwin Robert, A.; Almonea, K.I.; Al Dawish, M.A. Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Comparison of Holidays versus Schooldays. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2024, 20, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cato, A.; Hershey, T. Cognition and type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabetes Spectr. 2016, 29, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Patients | 138 | 81 |

| Gender (M/F) | ||

| Males | 47% | 43% |

| Females | 53% | 57% |

| Age | ||

| 0–6 years | 3% | 0% |

| 7–8 years | 7% | 2% |

| 9–11 years | 11% | 9% |

| 12–17 years | 53% | 19% |

| 18–21 years | 26% | 7% |

| ≥21 years | 0% | 63% |

| Season-Year | MDI | AHCL |

|---|---|---|

| Autumn-2022 | 33% | 57% |

| Winter-2022 | 30% | 59% |

| Spring-2023 | 30% | 62% |

| Summer-2023 | 31% | 58% |

| Parameter | Recommended Value | % of Patients Autumn 2022 (MDI-AHCL) | % of Patients Winter 2022 (MDI-AHCL) | % of Patients Spring 2023 (MDI-AHCL) | % of Patients Summer 2023 (MDI-AHCL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAR (>250 mg/dL) | <5% | 60–85% | 55–83% | 63–86% | 60–83% |

| TAR (181–250 mg/dL) | <25% | 78–96% | 71–98% | 73–92% | 79–96% |

| TIR (70–180 mg/dL) | >70% | 27–28% | 26–42% | 27–46% | 21–45% |

| TBR (54–69 mg/dL) | <4% | 100–98% | 98–96% | 98–98% | 93–98% |

| TBR (<54 mg/dL) | <1% | 100–96% | 100–96% | 100–96% | 100–98% |

| One Year | Heatwave | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean [mg/dL] | 17.24 | 15.33 |

| Std.Dev. [mg/dL] | 6.04 | 19.18 |

| RMSE [mg/dL] | 18.26 | 24.55 |

| Median [mg/dL] | 17.13 | 19.72 |

| Max [mg/dL] | 34.04 | 45.96 |

| MAD [mg/dL] | 4.81 | 15.43 |

| Parameter | Recommended Value | % of Patients MDI-SD | % of Patients MDI-NSD | % of Patients AHCL-SD | % of Patients AHCL-NSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | ≤36% | 39% | 32% | 62% | 56% |

| TAR (>250 mg/dL) | <5% | 67% | 75% | 84% | 82% |

| TAR (181–250 mg/dL) | <25% | 78% | 93% | 98% | 98% |

| TIR (70–180 mg/dL) | >70% | 19% | 7% | 34% | 22% |

| TBR (54–69 mg/dL) | <4% | 100% | 98% | 100% | 98% |

| TBR (<54 mg/dL) | <1% | 100% | 100% | 96% | 98% |

| MDI | AHCL | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean [mg/dL] | 1.97 | −1.14 |

| Std.Dev. [mg/dL] | 7.06 | 3.49 |

| RMSE [mg/dL] | 7.33 | 3.67 |

| Median [mg/dL] | 1.84 | −1.34 |

| Max [mg/dL] | 17.94 | 10.51 |

| MAD [mg/dL] | 5.63 | 2.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mascitelli, A.; Tumini, S.; Chiacchiaretta, P.; Aruffo, E.; Sacrini, L.; Saltarelli, M.A.; Di Carlo, P. Effect of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycemic Patterns of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Analysis as a Function of Different Therapeutic Treatments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121850

Mascitelli A, Tumini S, Chiacchiaretta P, Aruffo E, Sacrini L, Saltarelli MA, Di Carlo P. Effect of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycemic Patterns of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Analysis as a Function of Different Therapeutic Treatments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121850

Chicago/Turabian StyleMascitelli, Alessandra, Stefano Tumini, Piero Chiacchiaretta, Eleonora Aruffo, Lorenza Sacrini, Maria Alessandra Saltarelli, and Piero Di Carlo. 2025. "Effect of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycemic Patterns of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Analysis as a Function of Different Therapeutic Treatments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121850

APA StyleMascitelli, A., Tumini, S., Chiacchiaretta, P., Aruffo, E., Sacrini, L., Saltarelli, M. A., & Di Carlo, P. (2025). Effect of Atmospheric Temperature Variations on Glycemic Patterns of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Analysis as a Function of Different Therapeutic Treatments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121850