Effective Model of Emerging Disease Prevention and Control in a High-Epidemic Area, Chiang Rai Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

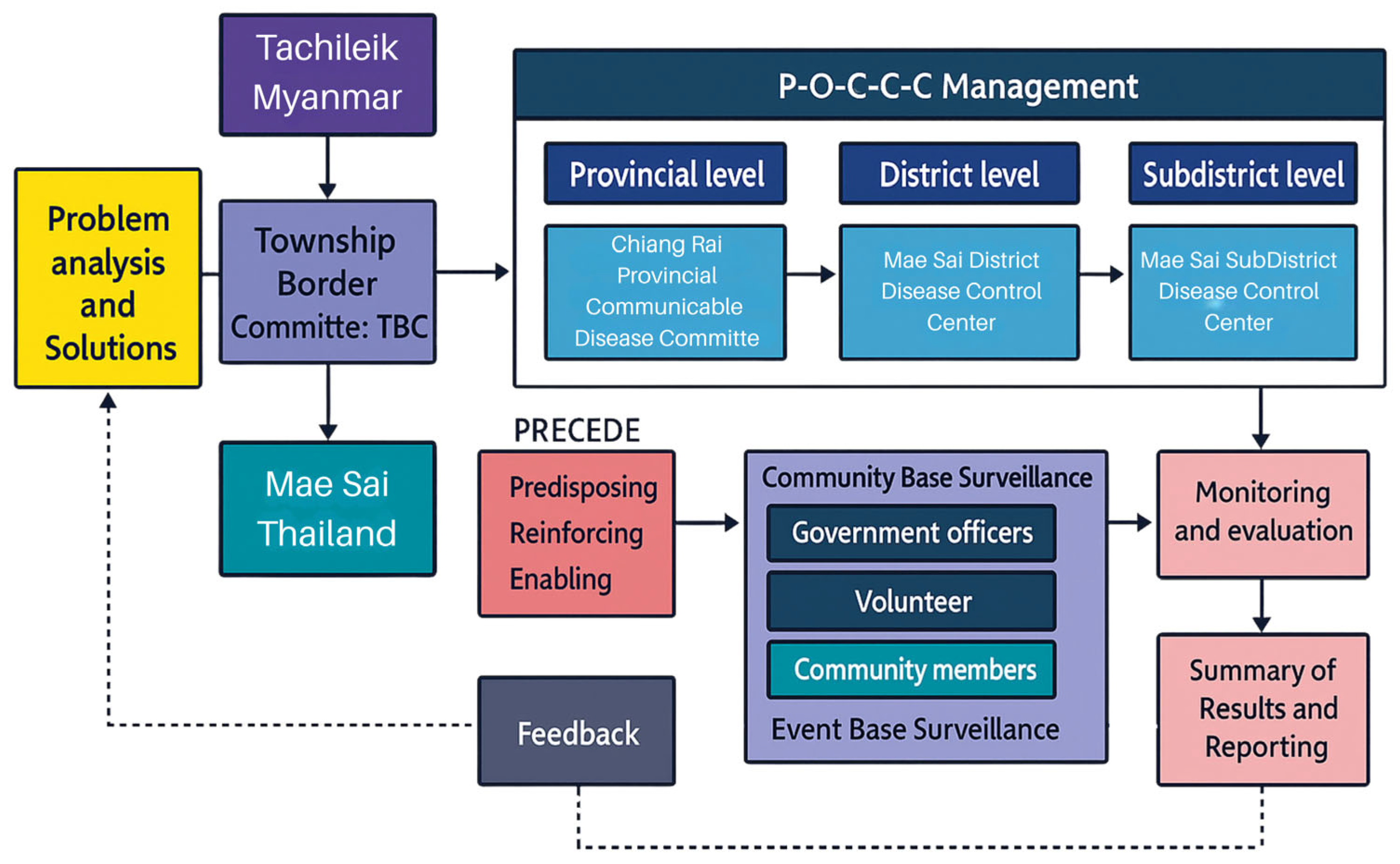

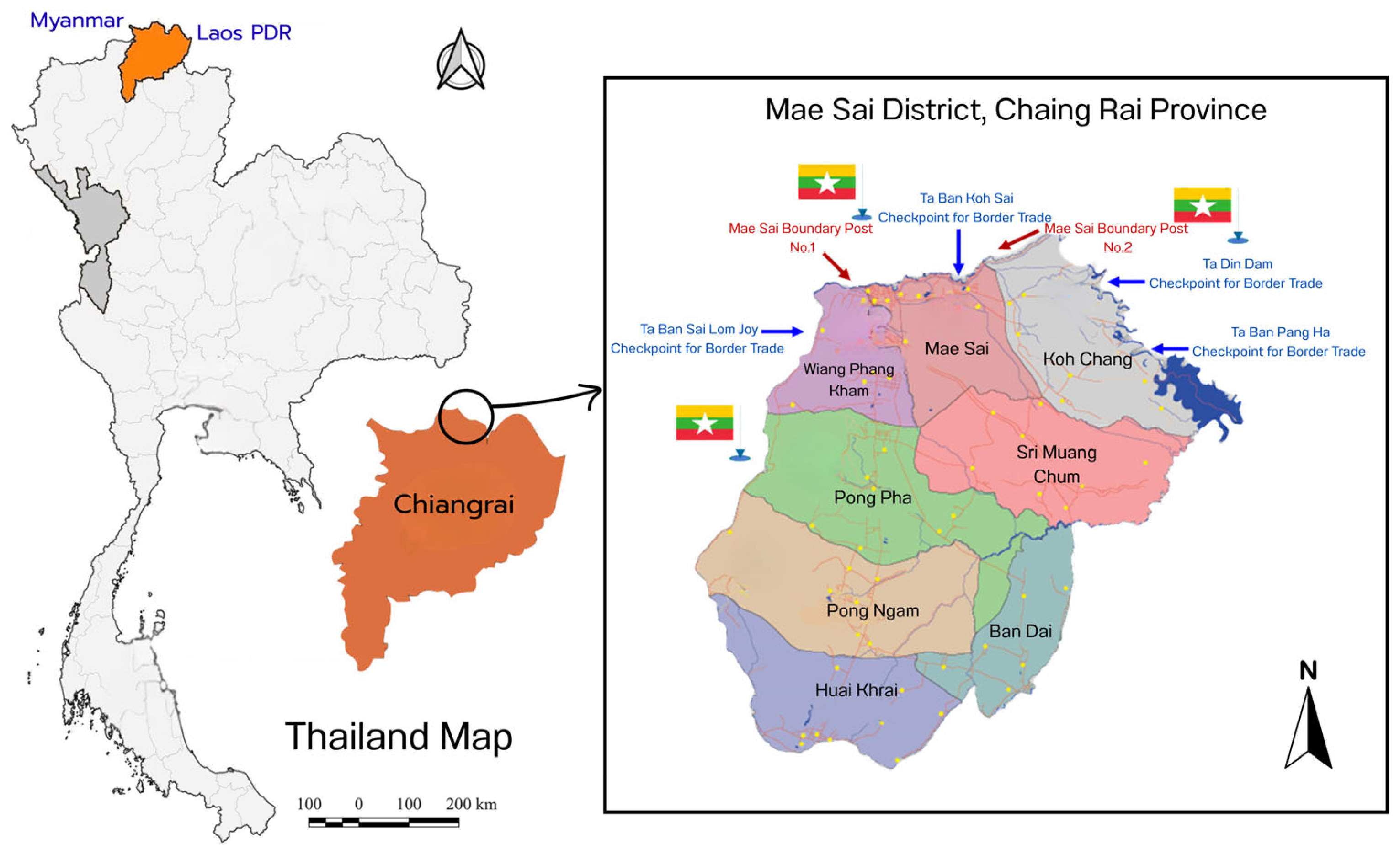

2.1. Study Design and Study Setting

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

- The sample size was calculated using W.G. Cochran’s formula [24], and there were 346 participants in total.

- Proportionate stratified random sampling was used to ensure an even distribution of participants from each village based on population proportions.

- The sample from each village was selected using probability sampling through simple random sampling by drawing lots from a list of target individuals, following inclusion criteria: individuals aged 20 and above, residing in Mae Sai Subdistrict for at least one year, willing to participate in the study, and able to communicate in Thai.

- 2.1 Village Health Volunteers and Migrant Health Volunteers: The sample size was calculated using W.G. Cochran’s formula [25], resulting in 197 participants.

- ○

- Inclusion criteria: volunteers with at least six months of experience in COVID-19 surveillance, prevention, and control who are willing to participate in the study.

- 2.2 Community Leaders, Territorial Defense Volunteers, Civil Defense Volunteers, and Village Security Teams: These were selected through purposive sampling, with a total of 36 participants.

- ○

- Inclusion criteria: volunteers with at least six months of experience in COVID-19 surveillance, prevention, and control who are willing to participate in the study.

- Selected through purposive sampling with the following inclusion criteria: officials with at least six months of experience in COVID-19 surveillance, prevention, and control in Mae Sai District and willing to participate in the study.

- ○

- 3.1 Health Officials in Mae Sai Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital: 10 participants.

- ○

- 3.2 Local Government Officials in Mae Sai Subdistrict: 10 participants.

- ○

- 3.3 Security Officials in the area, including immigration police and military personnel: 10 participants.

- There were 12 participants (one person from each of the 12 villages, with each village having one Thai representative and one migrant representative).

- Total of 12 participants:

- ○

- Three Village Health Volunteers.

- ○

- Three Migrant Health Volunteers.

- ○

- Three Community Leaders.

- ○

- One Territorial Defense Volunteer.

- ○

- One Civil Defense Volunteer.

- ○

- One Village Security Team Member.

- Total of 15 participants:

- ○

- Five Health Officials from the Subdistrict Health-Promoting Hospital.

- ○

- Four Local Government Officials from Mae Sai Subdistrict.

- ○

- Two Immigration Police Officers.

- ○

- Three Military Personnel.

2.3. Research Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

- Statistics were used for quantitative data analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed for all sections of the questionnaires using SPSS version 23. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Composite scores for variables in Parts II–V were converted to percentage scores and classified into three levels according to Bloom’s cutoff criteria: low (<60%), moderate (60–79%), and high (80–100%) [26]. Spearman rank correlations were used to detect the correlation at the significant level of alpha = 0.05. Multiple regression analysis was also performed to identify predictors of COVID-19 prevention and control behaviors.

- Qualitative data were analyzed using a conventional content analysis approach. Line-by-line open coding was conducted on the interview and focus group transcripts, after which similar codes were grouped into categories and developed into higher-order themes aligned with the study framework. To enhance analytical rigor, two researchers independently coded a subset of transcripts, and coding discrepancies were discussed and resolved through a consensus-based process. Data saturation was considered to have been reached when no new codes or themes emerged across successive interviews and focus groups. Methodological triangulation was undertaken by comparing themes across participant levels (general public, volunteers, and government officials) and by cross-validating qualitative findings with quantitative results.

2.5. Ethics Consideration

3. Results

General Characteristics of Participants

“In the early phase, we focused on preparedness by ensuring resources and preventive measures were in place, including monitoring the situation and educating the public on protective measures.”(Local Administrative Officer 1, 29 October 2022, Interview No. 04)

“A simulation exercise involved government agencies, private organizations, local administrative bodies, charitable organizations, public health personnel, village heads, and health volunteers—totaling 200 participants.”(International Disease Control Officer 2, 28 October 2022, Interview No. 06)

“More than 200 personnel from over 70 CDCU teams across the province were trained in public health emergency response. We also developed a comprehensive data system to manage emergencies effectively.”(Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital Officer 1, 27 September 2022, Interview No. 01)

“At the organizational level, the Provincial Communicable Disease Committee was the first to be formed, followed by the establishment of a district-level Emergency Operations Center (EOC), led by the Director of Mae Sai Hospital and the District Public Health Officer, with supporting committees structured under the Public Health Incident Command System.”(International Disease Control Officer 1, 28 October 2022, Interview No. 07)

“The EOC is the core of emergency response, functioning as a shared operational space for various agencies under the incident command system. It facilitates decision-making, coordination, and the rapid exchange of information and resources during the COVID-19 outbreak.”(Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital Officer 1, 27 September 2022, Interview No. 02)

“The District Chief Officer acted as the Incident Commander at the district level, demonstrating strong leadership, experience, and commitment to problem-solving. With multiple committees and agencies involved, communication was clear, fostering mutual understanding and reducing confusion in implementing orders.”(Local Administrative Officer 3, 29 October 2022, Interview No. 05)

“Information was mainly shared via LINE application. When a COVID-19 case was detected, it was reported from the Mae Sai Hospital outbreak center to the local health-promoting hospital (HPH), which then informed community leaders and village health volunteers. The HPH also reported cases to the Subdistrict Disease Control Operations Center to monitor patients and quarantined individuals, allowing local administrative organizations to provide necessary support.”(Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital Officer 1, 27 September 2022, Interview No. 01)

“There was no direct coordination with Myanmar due to the border closure. The International Communicable Disease Control Unit handled communication. In cases of illegal border crossings, military forces were responsible for apprehension and notified the police, who then informed Immigration and District Health Authorities for disease screening. Law enforcement dealt with arrests and deportations, except for Thai nationals, who were subject to fines or legal action.”(Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital Officer 1, 27 September 2022, Interview No. 03)

“There were multiple channels for enforcing control measures. In Mae Sai, the four main channels included international checkpoints managed by the Disease Control Unit and Immigration, border trade checkpoints (which were temporarily closed), natural border crossings, which posed the biggest challenge due to frequent illegal crossings, and community-level monitoring handled by local health authorities and community networks.”(International Disease Control Officer 2, 28 October 2022, Interview No. 07)

“For event control measures, organizers had to seek district approval and document compliance, reporting to the local health unit and the Subdistrict Disease Control Operations Center.”(Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital Officer 2, 27 September 2022, Interview No. 01)

4. Discussion

- General Public

- 2.

- Volunteer Workers

- 3.

- Government Officials

5. Limitations

- Although the study included three stakeholder levels (community members, volunteer workers, and government officials), the sample sizes across these levels were not balanced, which limited the ability to compare differences between levels.

- The study was unable to perform multivariate regression to adjust for confounders due to small and unbalanced sublevel sizes, particularly the limited number of government officials (n = 30), which may leave some residual confounding.

- Older adults, who represent a key high-risk population for COVID-19, were underrepresented in the sample, which may reduce the applicability of the findings to this age group.

- Although a mixed-methods approach was employed, the quantitative sample sizes for some sublevels remained limited, potentially affecting statistical power and the stability of correlation estimates.

- The cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data restrict causal interpretation and may introduce recall and social desirability biases in reporting preventive behaviors.

- Purposive sampling and the focus on a single border district limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions with different sociocultural or migration contexts.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aylin, Ç.U.; Budak, G.; Karabay, O.; Güçlü, E.; Okan, H.D.; Vatan, A. Main symptoms in patients presenting in the COVID-19 period. Scott. Med. J. 2020, 65, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Alqahtani, M.M.; Arnout, B.A.; Fadhel, F.H.; Sufyan, N.S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 and its impact on precautionary behavior: A qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldmeter COVID. COVID Live Update. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Chiang Rai Provincial Public Health Office. COVID-19 Situation Report Chiang Rai Province. 2023. Available online: https://cro.moph.go.th/mophcr-data/web/index.php?r=report/report_term (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Kasetsart University. Government Outbreak Control Measures. 2021. Available online: https://learningcovid.ku.ac.th/course/?c=8&l=1 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Rajatanavin, N.; Tuangratananon, T.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Responding to the COVID-19 second wave in Thailand by diversifying and adapting lessons from the first wave. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triukose, S.; Nitinawarat, S.; Satian, P.; Somboonsavatdee, A.; Chotikarn, P.; Thammasanya, T.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Sudhinaraset, N.; Boonyamalik, P.; Kakhong, B.; et al. Effects of public health interventions on the epidemiological spread during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakphanit, N. Lesson Learned from the Management of the COVID-19 Pandemic Situation in 2019 by the COVID-19 Situation Administration Center. Bangkok; Chulalongkorn University Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Plipat, T. Lessons from Thailand’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Thai J. Public Health 2020, 50, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Yorsaeng, R.; Suntronwong, N.; Thongpan, I.; Chuchaona, W.; Lestari, F.B.; Pasittungkul, S.; Puenpa, J.; Atsawawaranunt, K.; Sharma, C.; Sudhinaraset, N.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 and control measures on public health in Thailand, 2020. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasatpibal, N.; Viseskul, N.; Untong, A.; Thummathai, K.; Kamnon, K.; Sangkampang, S.; Tokilay, R.; Assawapalanggool, S.; Apisarnthanarak, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Thai population: Delineating the effects of the pandemic and policy measures. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2023, 3, e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Disease Control. The Department of Disease Control Requests Strict Cooperation from the Public to Continuously Adhere to the D-M-H-T-T-A Measures to Prevent COVID-19. 2023. Available online: https://ddc.moph.go.th/brc/news.php?news=18373&deptcode=brc%0A (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Doydee, P.; Chamnan, P.; Panpeng, J.; Pal, I. Government and public health measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on fisheries and aquaculture in Thailand. Pandemic Risk Response Resil. 2022, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Ounsaneha, W.; Laosee, O.; Suksaroj, T.T.; Rattanapan, C. Preventive Behaviors and Influencing Factors among Thai Residents in Endemic Areas during the Highest Epidemic Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.W.; Gielen, A.C.; Ottoson, J.M.; Peterson, D.V.; Kreuter, M.W. Health Program Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation; The United States of America on Acid-Free: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022; p. 488. Available online: https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/12101/health-program-planning-implementation-and-evaluation#book__details (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Rojpaisarnkit, K. Factors Influencing Well-Being in the Elderly Living in the Rural Areas of Eastern Thailand. Int. J. Behav. Sci. 2016, 11, 31–50. Available online: http://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/63277 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Rungnoei, N.; Dittabunjong, P.; Klinhom, P.; Krutakart, S.; Gettong, N. Factors Predicting Monitoring and Preventive Behaviors of COVID-19 among Nursing Students. Princess Naradhiwas Univ. J. 2022, 14, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.J.; Okuda, K.; Edwards, C.E.; Martinez, D.R.; Asakura, T.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Kato, T.; Lee, R.E.; Yount, B.L.; Mascenik, T.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell 2020, 182, 429–446.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asemahagn, M.A. Factors determining the knowledge and prevention practice of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Trop. Med. Health 2020, 48, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meemon, N.; Paek, S.C.; Pradubmook Sherer, P.; Keetawattananon, W.; Marohabutr, T. Transnational Mobility and Utilization of Health Services in Northern Thailand: Implications and Challenges for Border Public Health Facilities. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211053740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichai, C. Cultural Identities in Multicultural Ethnic Societies in the Chiang Rai Special Border Economic Zone. Thai J. East Asian Stud. 2021, 25, 32–34. Available online: https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/easttu/article/view/243487 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Chotipityanont, N. POCCC Management Theory and Henri Fayol’s Principles of Organizational Success. 2021. Available online: https://elcpg.ssru.ac.th/natnicha_ha/pluginfile.php/26/block_html/content/MPP5504%201_64%20%281%29%20New.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Cochran, W.G.; Mosteller, F.; Tukey, J.W. Statistical problems of the Kinsey report. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1953, 48, 673–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.J. Taxonomy of Education Objective; Handbook1 Cognitive Domain; McGraw-Hill Book: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). SDG Profile Chiang Rai. Bangkok: UNDP Thailand. 2023. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-06/sdg_profile_chiang_rai.pdf_english_0.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Hillsdale; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mae Sai Mittraphap Subdistrict Municipality. General Information of Mae Sai Mittraphap Subdistrict. 2022. Available online: https://www.maesaimittraphap.go.th/main.php?type=1 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Khumsaen, N. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Preventive Behaviorsof COVID-19 among People LivinginAmphoeU-thong, Suphanburi Province. J. Pr. Coll. Nurs. Phetchaburi Prov. 2021, 4, 33–48. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B.L.; Luo, W.; Li, H.M.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Liu, X.G.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariyasakulwong, P.; Charoenkitkarn, V.; Pinyopasaku, W.; Sriprasong, S.; Roubsanthisuk, W. Factors Influencing on Health Promoting Behaviors in Young Adults with Hypertension. Princess Naradhiwas Univ. J. 2015, 7, 26–36. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/pnujr/article/view/52671 (accessed on 6 October 2025). (In Thai).

- Yoo, H.J.; Song, E. Effects of personal hygiene habits on self-efficacy for preventing infection, infection-preventing hygiene behaviors, and product-purchasing behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Western Pacific Region. Role of Primary Care in the COVID-19 Response. 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Salakham, W.; Tanapad, J.; Taloy, T.; Chotthititham, N.; Uttama, P.; Prakat, P.; Prakat, P.; Oop-Kaew, P.; Nowanghan, S.; Katsomboon, K. Correlation of Perception Disease Severity to Implementation Role for Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Communities among Village Health Volunteers, Phrae Province. J. Res. Innov. Evid. Based Healthc. 2019, 1, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Panyathorn, K.; Sapsirisopa, K.; Tanglakmankhong, K.; Krongyuth, W. Community Participation in COVID-19 Prevention at Nongsawan Village, Chiangpin Sub-district, Mueang District, Udonthani Province. J. Phrapokklao Nurs. Coll. 2021, 32, 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Nawsuwan, K.; Singweratham, W.; Damsangsawas, N. Correlation of perception disease severity to implementation role for control of COVID-19 in communities among village health volunteers in Thailand. J. Bamrasnaradura Infect. Dis. Inst. 2020, 14, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Siuki, H.A.; Peyman, N.; Vahedian-Shahroodi, M.; Gholian-Aval, M.; Tehrani, H. Health Education Intervention on HIV/AIDS Prevention Behaviors among Health Volunteers in Healthcare Centers: An Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2019, 45, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supanyabut, S. Affecting factors and impacted to preventive behavior on the influenza type A (subtype 2009 H1N1) of the population in Namon District, Kalasin Province. J. Off. ODPC 7 Khon Kaen 2011, 18, 1–11. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Yaebkai, Y.; Wongsawat, P. Main Role Performances of Village Health Volunteers. J. Phrapokklao Nurs. Coll. 2020, 31, 269–279. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/pnc/article/view/245517 (accessed on 10 March 2024). (In Thai).

- Wonhti, S. Factors Affecting Preventive Behavior for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Village Health Volunteers, Sukhothai Province; Naresuan University: Phitsanulok, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Siriphakhamongkhon, S.; Siriphakhamongkhon, S.; Ongat, P.; Apiwachaneewong, S. Causal Relationship Model of Prevention and Control Service: Primary Care Unit in Public Health Region 3rd. Dis. Control J. 2021, 47, 1072–1082. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/DCJ/article/view/245294 (accessed on 10 March 2024). (In Thai).

- Chum-in, C.; Intharat, S.; Vinchuan, S.; Pandum, T.; Nuiyput, A.; Dongnadeng, H. The Mechanism in Services During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Case Study of Ban Khlong Muan Health Promoting Hospital of Nong Prue Subdistrict, Ratsada District, Trang Province. J. Leg. Entity Manag. Local Innov. 2021, 7, 295–309. Available online: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jsa-journal/article/view/251033/171080 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Pietig, M. Communication Is Key To Patient Experience During and After COVID. 2020. Available online: https://electronichealthreporter.com/communication-is-key-to-patient-experience-during-and-after-cvoid/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Janmuan, P. Factors Affecting Preventive Behavior for Coronavirus Disease 2019 among Public Health Personnel of the public health service centers network in the Khon Kaen Hospital. J. Health Environ. Educ. 2023, 8, 98–108. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, C.; Meskell, P.; Delaney, H.; Smalle, M.; Glenton, C.; Booth, A.; Chan, X.H.S.; Devane, D.; Biesty, L.M. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: A rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, CD013582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deesawat, C.; Geerapong, P.; Pensirinapa, N. Factors Affecting Safety Behaviorsfor Preventing Novel Coronavirus-2019 Infection among Personnel in Buriram Hospital. Reg. Health Promot. Cent. 9 J. 2021, 15, 399–413. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kanchaiyaphum, K. Developing a Management Model for The Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) with a Mechanism for Improving Quality of Life at the District Level Khon Sawan District Chaiyaphum Province. J. Environ. Educ. Med. Health 2022, 7, 66–75. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Plianpanich, S.; Suriyon, N.; Kanthawee, P. The Development of Communicable Disease and Emerging Disease Surveillance, Prevantion and Control System along Thai-Myanmar and Thai-Lao PDR, Border Areas Chiang Rai Province, 2017–2018. Dis. Control J. 2019, 45, 85–96. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Ketdao, R.; Thiengtrongdee, A.; Thoin, P. Development of Covid-19 Surveillance Prevention and Control Model Health Promoting Hospital in Sub-district Level, Udonthani Province-Udon Model COVID-19. J. Health Sci. Thai 2021, 30, 53–61. Available online: https://thaidj.org/index.php/JHS/article/view/9845 (accessed on 10 March 2024). (In Thai).

- Chuenchom, P.; Yodsuwan, S.; Ployleaung, T.; Muenchan, P.; Kanthawee, P. The development of COVID-19 epidemic management system at Thai-Laos Border: A case study Chiangkong District, Chiangrai Province. Chiangrai Med. J. 2022, 14, 71–92. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Thaewnongiew, K.; Mongkonsin, C.; Chantaluk, S.; Valaisathaen, T.; Treedetch, S.; Watthanawong, O.; Lamoonsil, S. Sub-district health management evaluation of liver flukes and cholangiocarcinoma surveillance, prevention and controlin 7th health area. J. Off. DPC 7 Khon Kaen 2018, 25, 77–87. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kitphati, R.; Krates, J.; Ruangrattanatrai, W.; Nak-Ai, W.; Muangyim, K. Public Health Emergency Situation Management and National Policy Recommendation for COVID-19 Pandemic Attributed from 8-Context Specific in Thailand. J. Health Sci. Thai 2022, 30, 975–997. Available online: https://thaidj.org/index.php/JHS/article/view/11560 (accessed on 10 March 2024). (In Thai).

- Ministry of Public Health. COVID-19 Outbreak Situation Reports for Border Provinces; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Tak Provincial Public Health Office. Mae Sot Cross-Border Transmission Report; Tak Provincial Public Health Office: Tak, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration Cross-Border Mobility COVID-19 Response in the, G.M.S.; Bangkok. 2022. Available online: https://thailand.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1371/files/documents/Human_Mobility%20in%20the%20GMS_external_final_0.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Chiang Rai Provincial Public Health Office. Evaluation of Communicable Disease Control in Border Districts; Chiang Rai Provincial Public Health Office: Chiang Rai, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H. Temporal changes in psychobehavioural responses during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, D.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk Perceptions of COVID-19 around the World. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Hove, T. Information Communication Technologies (ICTs), Crisis Communication Principles and the COVID-19 Response in South Korea. J. Creat. Commun. 2021, 16, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N.; Mishra, S.R.; Ghimire, S.; Gyawali, B.; Marahatta, S.B.; Maskey, S.; Baral, S.; Shrestha, N.; Yadav, R.; Pokharel, S. Health System Preparedness for COVID-19 and Its Impacts on Frontline Health-Care Workers in Nepal: A Qualitative Study Among Frontline Health-Care Workers and Policy-Makers. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 2560–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Community Member | Volunteer | Government Officials | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 346 | 100.0 | 233 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 139 | 40.2 | 120 | 51.5 | 12 | 40.0 |

| Female | 207 | 59.8 | 113 | 48.5 | 18 | 60.0 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 58 | 16.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 26.7 |

| 30–39 | 76 | 22.0 | 21 | 9.0 | 11 | 36.7 |

| 40–49 | 76 | 22.0 | 80 | 34.3 | 5 | 16.5 |

| 50–59 | 98 | 28.3 | 93 | 39.9 | 6 | 20.0 |

| ≥60 | 38 | 11.0 | 39 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 127 | 36.7 | 36 | 15.5 | 16 | 53.3 |

| Married | 184 | 53.2 | 173 | 74.2 | 12 | 40.0 |

| Widowed/Divorced | 26 | 7.5 | 9 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhist | 318 | 91.9 | 221 | 94.8 | 26 | 86.7 |

| Christian | 17 | 4.9 | 12 | 5.2 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Islamic | 10 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Unreligious | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Education | ||||||

| Unlettered | 90 | 26.0 | 23 | 9.9 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Elementary School | 114 | 32.9 | 93 | 39.9 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Secondary School | 39 | 11.3 | 40 | 17.2 | 20 | 66.7 |

| High School | 52 | 15.0 | 57 | 24.5 | 6 | 20.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 34 | 9.8 | 20 | 8.6 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Master’s Degree | 6 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 10.0 |

| Medical treatment rights | ||||||

| Universal Coverage Scheme | 235 | 67.9 | 193 | 82.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Social Security Fund | 36 | 10.4 | 18 | 7.7 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Stateless People | 34 | 9.8 | 13 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| No rights | 30 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme | 11 | 3.2 | 9 | 3.9 | 20 | 66.7 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Employee | 173 | 50.0 | 130 | 55.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Merchant | 63 | 18.2 | 40 | 17.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Agriculturist | 27 | 7.8 | 40 | 17.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Housekeeper | 24 | 6.9 | 15 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Government Officer | 13 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.4 | 20 | 66.7 |

| Government Employee | 4 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Self-Employed. | 6 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| State Enterprise | 3 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unemployed | 17 | 4.9 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Students | 13 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Freelance | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| History of COVID-19 infection | ||||||

| Yes | 265 | 76.6 | 184 | 79.0 | 21 | 70.0 |

| No | 81 | 23.4 | 49 | 21.0 | 9 | 30.0 |

| Place of treatment | ||||||

| Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital | 34 | 12.8 | 8 | 3.4 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Mae Sai Hospital | 62 | 17.9 | 56 | 24.0 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Kasemrad Sriburin Hospital Mae Sai | 8 | 2.3 | 17 | 7.3 | 2 | 6.7 |

| Community isolation (CI) | 26 | 7.5 | 11 | 4.7 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Home isolation (HI) | 135 | 39.0 | 92 | 39.5 | 13 | 43.3 |

| History of vaccination | ||||||

| Yes | 335 | 96.8 | 231 | 99.1 | 30 | 100.0 |

| No | 11 | 3.2 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Number of vaccinations (Dose) | ||||||

| 1 | 4 | 1.2 | 11 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 181 | 52.3 | 60 | 26.0 | 1 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 140 | 40.5 | 125 | 54.1 | 9 | 30.0 |

| 4 | 10 | 2.9 | 35 | 15.2 | 20 | 66.7 |

| Factors | Community Member (n = 346) | Volunteer (n = 233) | Government Officials (n = 30) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Predisposing | ||||||

| Perception | ||||||

| Low | 6 | 1.7 | 10 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Moderate | 10 | 2.9 | 20 | 8.6 | 2 | 6.7 |

| High | 330 | 95.4 | 203 | 87.1 | 28 | 93.3 |

| Attitude | ||||||

| Low | 5 | 1.4 | 54 | 23.2 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Moderate | 18 | 5.2 | 114 | 48.9 | 21 | 70.0 |

| High | 323 | 93.4 | 65 | 27.9 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Reinforcing | ||||||

| Social support | ||||||

| Low | 28 | 8.1 | 19 | 8.2 | 16 | 53.3 |

| Moderate | 13 | 3.8 | 12 | 5.2 | 4 | 13.3 |

| High | 305 | 88.2 | 202 | 86.7 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Participation | ||||||

| Low | 34 | 9.8 | 55 | 23.6 | 9 | 30.0 |

| Moderate | 57 | 16.5 | 45 | 19.3 | 11 | 36.7 |

| High | 255 | 73.7 | 133 | 57.1 | 10 | 33.3 |

| Enabling | ||||||

| Service | ||||||

| Low | 21 | 6.1 | 24 | 10.3 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Moderate | 42 | 12.1 | 63 | 27.0 | 11 | 36.7 |

| High | 283 | 81.8 | 146 | 62.7 | 15 | 50.0 |

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| Prevention and control of behavior | ||||||

| Low | 24 | 6.9 | 8 | 3.4 | 4 | 13.3 |

| Moderate | 12 | 3.5 | 28 | 12.0 | 5 | 16.7 |

| High | 310 | 89.6 | 197 | 84.5 | 21 | 70.0 |

| Factors | COVID-19 Preventive and Control Behaviors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Member (n = 346) | Volunteer (n = 233) | Government Officials (n = 30) | ||||

| r | p-Value | r | p-Value | r | p-Value | |

| Predisposing | ||||||

| Perception | 0.020 | 0.714 | 0.18 | 0.007 * | −0.17 | 0.363 |

| Attitude | 0.14 | 0.008 * | 0.26 | <0.001 * | −0.12 | 0.528 |

| Reinforcing | ||||||

| Social support | 0.66 | <0.001 * | 0.38 | <0.001 * | 0.50 | 0.005 * |

| Participation | 0.61 | <0.001 * | 0.10 | 0.143 | 0.47 | 0.008 * |

| Enabling | ||||||

| Service | 0.65 | <0.001 * | 0.16 | 0.015 | −0.32 | 0.090 |

| POCCC Component | Themes Identified | Example Codes | Frequency of Mentions (n) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P—Planning | Preparedness planning; simulation exercises; training and drills | “preparation before outbreak”, “simulation exercise”, “training personnel” | 14 | Highly emphasized across interviews |

| O—Organizing | Structure of provincial and district CDCU/EOC; formal operational system | “provincial committee”, “district EOC”, “incident command structure” | 18 | Most frequently mentioned component |

| C—Commanding | Unified incident commander; leadership capacity; chain of command | “district chief as commander”, “clear communication” | 12 | Leadership was a strong recurring theme |

| C—Coordinating | Cross-border coordination; inter-agency cooperation; informal networks | “TBC meetings”, “LINE coordination”, “informal channels” | 16 | Coordination challenges frequently noted |

| C—Controlling | Border control points; surveillance operations; community enforcement | “international checkpoints”, “natural routes”, “community monitoring” | 15 | Control operations were intensively described |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sangsuwan, J.; Kanthawee, P.; Inchon, P.; Markmee, P.; Chiraphatthakun, P. Effective Model of Emerging Disease Prevention and Control in a High-Epidemic Area, Chiang Rai Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121849

Sangsuwan J, Kanthawee P, Inchon P, Markmee P, Chiraphatthakun P. Effective Model of Emerging Disease Prevention and Control in a High-Epidemic Area, Chiang Rai Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121849

Chicago/Turabian StyleSangsuwan, Jiraporn, Phitsanuruk Kanthawee, Pamornsri Inchon, Phataraphon Markmee, and Phaibun Chiraphatthakun. 2025. "Effective Model of Emerging Disease Prevention and Control in a High-Epidemic Area, Chiang Rai Province" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121849

APA StyleSangsuwan, J., Kanthawee, P., Inchon, P., Markmee, P., & Chiraphatthakun, P. (2025). Effective Model of Emerging Disease Prevention and Control in a High-Epidemic Area, Chiang Rai Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121849