Balance, Gait Kinematics, and Fear of Falling After a Four-Month Targeted Training Program in a Patient with Cervical Dystonia: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

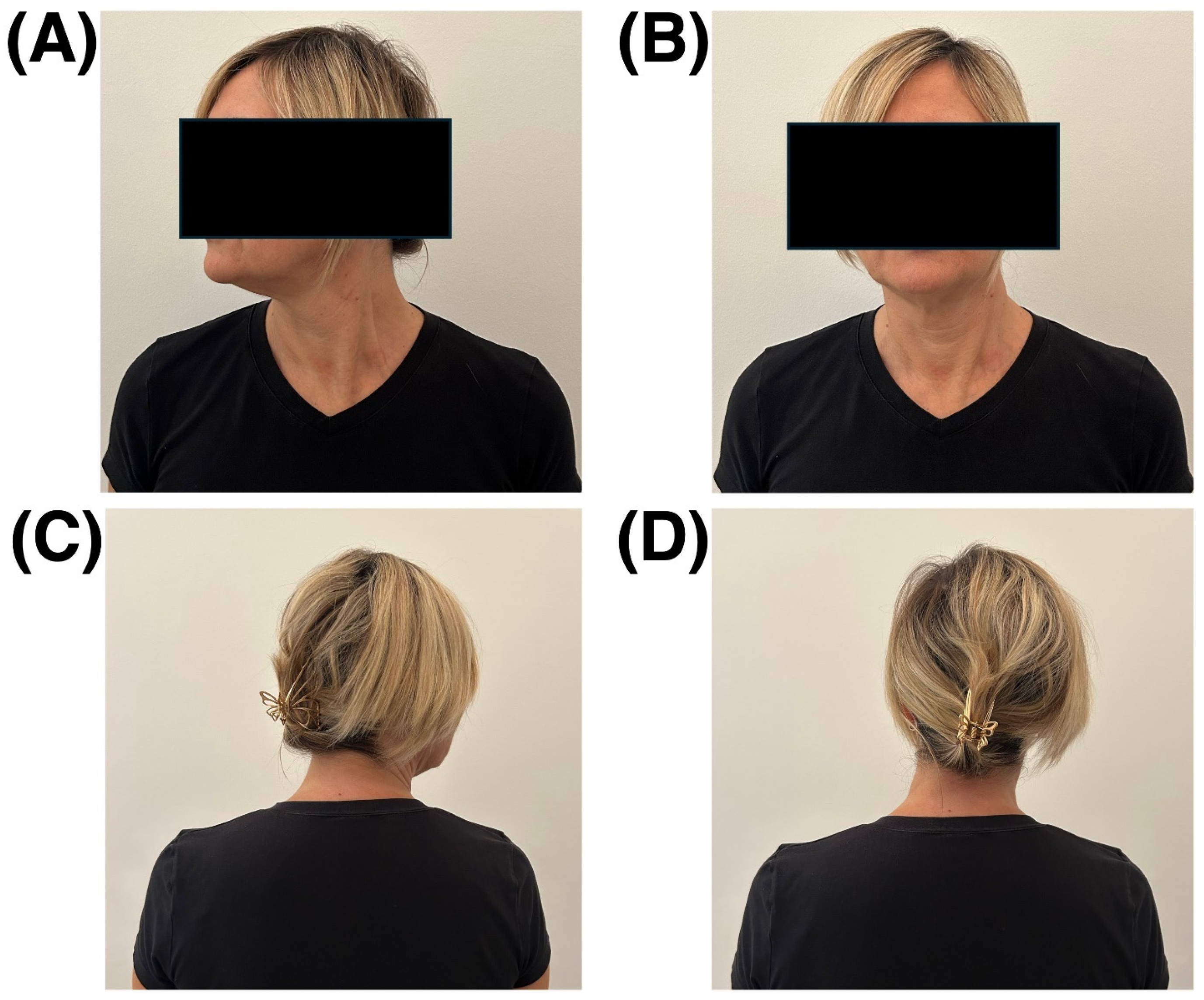

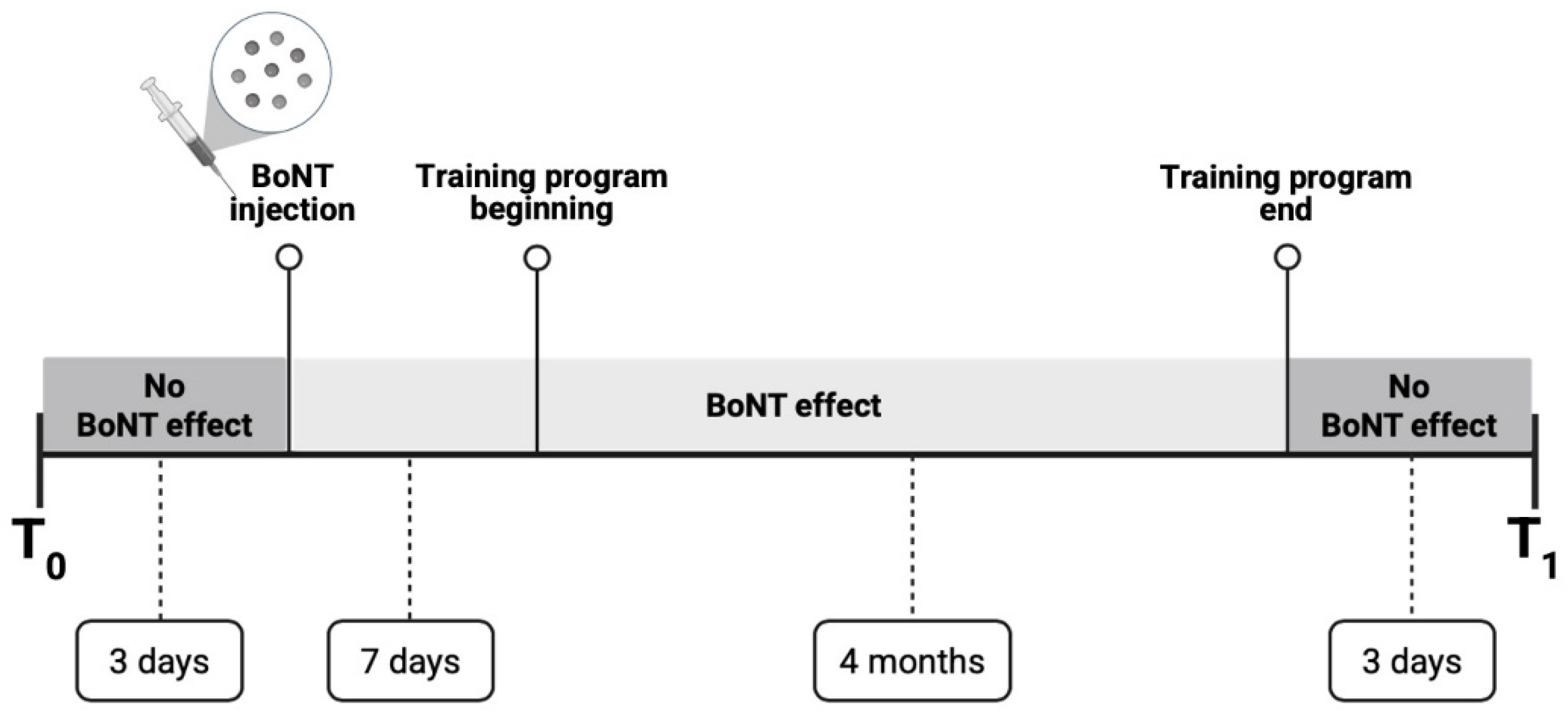

2. Case Presentation

3. Evaluation Methods and Training Program

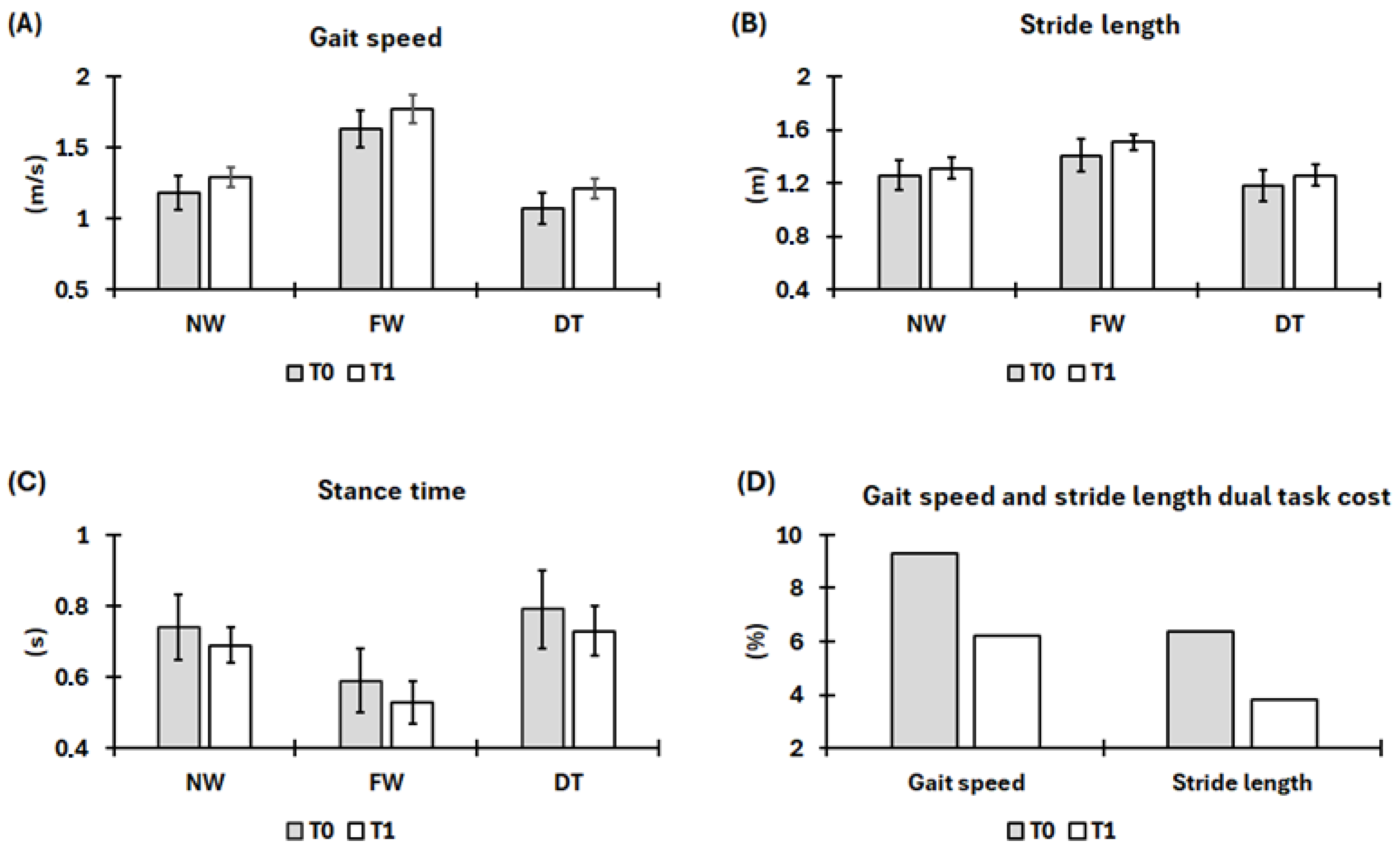

3.1. Gait Kinematics Assessment

3.2. Balance, Dynamic Stability and Fear of Falling Assessment

3.3. Training Program

4. Results and Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benson, M.; Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.P.; Cavillon, P.; Cuffe, L.; König, K.; Reinhard, C.; Graessner, H. Development of a patient journey map for people living with cervical dystonia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balint, B.; Mencacci, N.E.; Valente, E.M.; Pisani, A.; Rothwell, J.; Jankovic, J.; Vidailhet, M.; Bhatia, K.P. Dystonia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzino, L.; Cherif, A.; Crisafulli, O.; Carbone, F.; Zenzeri, J.; Morasso, P.; Abbruzzese, G.; Pelosin, E.; Konczak, J. Tactile and proprioceptive dysfunction differentiates cervical dystonia with and without tremor. Neurology 2020, 94, e639–e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggemann, N. Contemporary functional neuroanatomy and pathophysiology of dystonia. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Dool, J.; Tijssen, M.A.; Koelman, J.H.; Engelbert, R.H.; Visser, B. Determinants of disability in cervical dystonia. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 32, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, C.; Barnard, R.; Edwards, L.; Lennon, S.; Bradnam, L. Impairments of balance, stepping reactions and gait in people with cervical dystonia. Gait Posture 2017, 55, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, O.; Ravizzotti, E.; Mezzarobba, S.; Cosentino, C.; Bonassi, G.; Botta, A.; Abbruzzese, G.; Marchese, R.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E. A gait-based paradigm to investigate central body representation in cervical dystonia patients. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle Shukla, A.; Gurrala, A.; Vedam-Mai, V. Gait and balance in cervical dystonia and dystonic head tremor. Dystonia 2023, 2, 11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggelkow, S.; Kossev, A.; Moll, C.; Däuper, J.; Dengler, R.; Rollnik, J.D. Impaired sensorimotor integration in cervical dystonia: A study using transcranial magnetic stimulation and muscle vibration. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 19, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, M.; Brichetto, G.; Abbruzzese, G.; Marchese, R.; Schieppati, M. Postural responses to continuous unilateral neck muscle vibration in standing patients with cervical dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, R.J. Sensory integration for human balance control. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 159, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Honeine, J.L.; Crisafulli, O.; Schieppati, M. Body sway adaptation to addition but not withdrawal of stabilizing visual information is delayed by a concurrent cognitive task. J. Neurophysiol. 2017, 117, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martines, F.; Messina, G.; Patti, A.; Battaglia, G.; Bellafiore, M.; Messina, A.; Rizzo, S.; Salvago, P.; Sireci, F.; Traina, M.; et al. Effects of tinnitus on postural control and stabilization: A pilot study. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2015, 31, 907–912. [Google Scholar]

- Castelão, M.; Marques, R.E.; Duarte, G.S.; Rodrigues, F.B.; Ferreira, J.; Sampaio, C.; Moore, A.P.; Costa, J. Botulinum toxin type A therapy for cervical dystonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 12, Cd003633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbaud, P.; Ducerf, C.; Cugy, E.; Dubos, J.L.; Muller, F.; Guehl, D.; Dehail, P.; Cugy, D.; Moore, N.; Lagueny, A.; et al. Botulinum toxin treatment in neurological practice: How much does it really cost? A prospective cost-effectiveness study. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 1670–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassaye, S.G.; De Hertogh, W.; Crosiers, D.; Gudina, E.K.; De Pauw, J. The effectiveness of physiotherapy for patients with isolated cervical dystonia: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamo, H.; Nagaki, K.; Kraus, A.R.; Warren, L.; Wagle Shukla, A. Neurorehabilitation in Dystonia Care: Key Questions of Who Benefits, What Modalities, and When to Intervene. Dystonia 2025, 4, 14695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jimenez, M. Normal Changes in Gait and Mobility Problems in the Elderly. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 28, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debu, B.; De Oliveira Godeiro, C.; Lino, J.C.; Moro, E. Managing Gait, Balance, and Posture in Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, V.L.; Pompeu, J.E.; de Freitas, T.B.; Polese, J.; Torriani-Pasin, C. Physical activity level is associated with gait performance and five times sit-to-stand in Parkinson’s disease individuals. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022, 122, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Salazar, A.P.; Marchese, R.R.; Stein, C.; Pagnussat, A.S. The Effects of Hydrotherapy on Balance, Functional Mobility, Motor Status, and Quality of Life in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PM&R 2019, 11, 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Emeric, C.S.; McDermott, C.L.; Lee, D.S.; Berry, S.D. Risk Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older Community-Dwelling Adults: A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, S.Y.M.; Souza, A.F.; Penteado, I.F.; Veronez, D.; Teive, H.A.G. Do patients with cervical dystonia present a greater risk and more fear of falling? Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2025, 83, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, M.J.; Chang, F.C.F.; Mahant, N.; Fung, V.S.C.; Bradnam, L. A survey of falls in people with dystonia. Physiother. Res. Int. 2020, 25, e1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, L.T.; Oliveira-Ferreira, M.D.; Caetano, M.J.; Lirani-Silva, E.; Barbieri, F.A.; Stella, F.; Gobbi, S. Exercise programs improve mobility and balance in people with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2009, 15 (Suppl. S3), S49–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, M.; Munari, D.; Geroin, C.; Gajofatto, A.; Benedetti, M.D.; Midiri, A.; Carla, F.; Picelli, A.; Waldner, A.; Smania, N. Sensory integration balance training in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized, controlled trial. Mult. Scler. J. 2015, 21, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfa-Fatollahkhani, P.; Safar Cherati, A.; Habibi, S.A.H.; Shahidi, G.A.; Sohrabi, A.; Zamani, B. Effects of treadmill training on the balance, functional capacity and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized clinical trial. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, S.L.; Jacobs, J.V.; Ford, M.; Tourville, T.W. Effects of balance-specific exercises on balance, physical activity and quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: A pilot investigation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 2238–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Batista, C.; Corcos, D.M.; Kanegusuku, H.; Piemonte, M.E.P.; Gobbi, L.T.B.; de Lima-Pardini, A.C.; de Mello, M.T.; Forjaz, C.L.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Balance and fear of falling in subjects with Parkinson’s disease is improved after exercises with motor complexity. Gait Posture 2018, 61, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, M.J.; Canning, C.G.; Mahant, N.; Morris, J.; Latimer, J.; Fung, V.S. The Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale: Reliability in neurologists and physiotherapists. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, M.A.; Elble, R.J.; Ondo, W.G.; Wu, S.C.; Hulihan, J. Assessment of interrater and intrarater reliability of the Fahn-Tolosa-Marin Tremor Rating Scale in essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuinat, J.; Debû, B.; Meoni, S.; Pelissier, P.; Castrioto, A.; Fraix, V.; Moro, E. Spatiotemporal Gait Differences before and after Botulinum Toxin in People with Focal Dystonia: A Pilot Study. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2024, 11, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisafulli, O.; Trompetto, C.; Puce, L.; Marinelli, L.; Costi, S.; Abbruzzese, G.; Avanzino, L.; Pelosin, E. Dual task gait deteriorates gait performance in cervical dystonia patients: A pilot study. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, S. The ecological approach to cognitive-motor dual-tasking: Findings on the effects of expertise and age. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baione, V.; Ferrazzano, G.; Celletti, C.; De Rosa, M.; Belvisi, D.; Fabbrini, G.; Galli, M.; Camerota, F.; Conte, A. Attention-Demanding Cognitive Tasks Worsen Postural Control in Patients with Cervical Dystonia: A Case-Control Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 666438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.; Ekman, U.; Rennie, L.; Peterson, D.S.; Leavy, B.; Franzén, E. Dual-Task Effects During a Motor-Cognitive Task in Parkinson’s Disease: Patterns of Prioritization and the Influence of Cognitive Status. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2021, 35, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorio, R.; Hasegawa, N.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Nutt, J.G.; Horak, F.B.; Mancini, M.; Shah, V.V. Dual-Task Costs of Quantitative Gait Parameters While Walking and Turning in People with Parkinson’s Disease: Beyond Gait Speed. J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Iansek, R.; Matyas, T.; Summers, J. Abnormalities in the stride length-cadence relation in parkinsonian gait. Mov. Disord. 1998, 13, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godi, M.; Franchignoni, F.; Caligari, M.; Giordano, A.; Turcato, A.M.; Nardone, A. Comparison of reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the mini-BESTest and Berg Balance Scale in patients with balance disorders. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, A.; Mitchell, K.; Ellison, J.; Brewer, W.; Perry, L.A. Reliability and validity of modified Four Square Step Test (mFSST) performance in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023, 39, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere, K.; Close, J.C.; Mikolaizak, A.S.; Sachdev, P.S.; Brodaty, H.; Lord, S.R. The Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, N. Lower-extremity resistance training on unstable surfaces improves proxies of muscle strength, power and balance in healthy older adults: A randomised control trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzato, A.; Bozzato, M.; Rotundo, L.; Zullo, G.; De Vito, G.; Paoli, A.; Marcolin, G. Multimodal training protocols on unstable rather than stable surfaces better improve dynamic balance ability in older adults. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honeine, J.L.; Crisafulli, O.; Sozzi, S.; Schieppati, M. Processing time of addition or withdrawal of single or combined balance-stabilizing haptic and visual information. J. Neurophysiol. 2015, 114, 3097–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozzi, S.; Honeine, J.L.; Do, M.C.; Schieppati, M. Leg muscle activity during tandem stance and the control of body balance in the frontal plane. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Lower limb dynamic balance, strength, explosive power, agility, and injuries in volleyball players. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, M.; Hvid, L.G.; Thrue, C.; Johansson, S.; Franzén, E.; Dalgas, U.; Langeskov-Christensen, M. Muscle Strength and Power in People with Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2023, 47, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoni, G.; Crisafulli, O.; Pisegna, C.; Serra, M.; Brambilla, S.; Feletti, F.; Cremonte, G.; D’Antona, G. An 8-month adapted motor activity program in a young CMT1A male patient. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1347319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, O.; Baroscelli, M.; Grattarola, L.; Tansini, G.; Zampella, C.; D’Antona, G. Case report: Personalized adapted motor activity in a COVID-19 patient complicated by critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1035255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Jehu, D.A.; Daneshjoo, A.; Shakoor, E.; Razeghi, M.; Amani, A.; Hakim, M.N.; Yusof, A. Effects of 8 Weeks of Balance Training, Virtual Reality Training, and Combined Exercise on Lower Limb Muscle Strength, Balance, and Functional Mobility Among Older Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sports Health 2021, 13, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradsson, D.; Löfgren, N.; Nero, H.; Hagströmer, M.; Ståhle, A.; Lökk, J.; Franzén, E. The Effects of Highly Challenging Balance Training in Elderly with Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.; Folkerts, A.K.; Hammarström, I.; Kalbe, E.; Leavy, B. Effects of motor-cognitive training on dual-task performance in people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2890–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramontano, M.; Argento, O.; Orejel Bustos, A.S.; DE Angelis, S.; Montemurro, R.; Bossa, M.; Belluscio, V.; Bergamini, E.; Vannozzi, G.; Nocentini, U. Cognitive-motor dual-task training improves dynamic stability during straight and curved gait in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penko, A.L.; Barkley, J.E.; Koop, M.M.; Alberts, J.L. Borg scale is valid for ratings of perceived exertion for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 10, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.; Pimenta, S.; Garcia, A.L.; Nogueira, T.; Silva, S.; Oliveiros, B.; Martins, R.A.; Cruz, J. Home-Based Preoperative Exercise Training for Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Surgery: A Feasibility Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, O.; Lacetera, J.; Bottoni, G.; Berardinelli, A.; Grattarola, L.; Veltroni, M.; Acquadro, S.; Negro, M.; Lavaselli, E.; D’Antona, G. Case report: A creatine kinase-borg scale values-based approach to tailor physical training in a central core myopathy patient. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1404657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesinski, M.; Hortobágyi, T.; Muehlbauer, T.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Effects of Balance Training on Balance Performance in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, P.J.; Richmond, D.E.; Baskett, J.J. A prospective trial of serial gait speed as a measure of rehabilitation in the elderly. Age Ageing 1988, 17, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, C.J.; Bishop, M.; Moscovich, M.; Stegemöller, E.L.; Skinner, J.; Malaty, I.A.; Shukla, A.W.; McFarland, N.; Okun, M.S. Defining the clinically meaningful difference in gait speed in persons with Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2014, 38, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Hazzard, J.B.; Signorile, J.F.; Luca, C. Exercise Guidelines for Gait Function in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2018, 32, 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scataglini, S.; Van Bocxlaer, C.; Jansen, L.; Van Es, L.; Van Laerhoven, C.; Truijen, S. Influence of wearable rhythmic auditory stimulation on Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiš, P.; Bzdúšková, D.; Košutzká, Z.; Slobodová, L.; Straka, I.; Marček Malenovská, K.; Mytiai, O.; Tirpáková, V.; Konrády, P.; Litváková, V.; et al. Supervised aerobic-strength exercise reduces postural sway and improves dual-task gait in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osoba, M.Y.; Rao, A.K.; Agrawal, S.K.; Lalwani, A.K. Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brach, J.S.; Berthold, R.; Craik, R.; VanSwearingen, J.M.; Newman, A.B. Gait variability in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1646–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.H.; Yu, R.; Kang, M.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Woo, K.A.; Chang, H.J.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Jeon, B. High preoperative gait variability is a prognostic predictor of gait and balance in Parkinson disease patients with deep brain stimulation. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 100, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.A.; Richards, S.H.; Taylor, R.S.; Taylor, A.H.; Campbell, J.L. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Hassett, L.; Clark, R.; Bryant, A.; Olver, J.; Morris, M.E.; Ada, L. Improving Walking Ability in People with Neurologic Conditions: A Theoretical Framework for Biomechanics-Driven Exercise Prescription. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, E.; Beauchamp, M.K.; Astephen Wilson, J. Age and sex differences in normative gait patterns. Gait Posture 2021, 88, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Glenney, S.S. Minimal clinically important difference for change in comfortable gait speed of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkan, M.; Çobanoğlu, G.; Küpeli, B.; Ozkul, C.; Oskay, D.; Güzel, N.A. The reliability of a wearable movement analysis system (G-walk) on gait and jump assessment in healthy adults. J. Exerc. Ther. Rehabil. 2020, 7, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, B.; Joseph, C.; Löfgren, N.; Johansson, H.; Hagströmer, M.; Franzén, E. Outcome Evaluation of Highly Challenging Balance Training for People with Parkinson Disease: A Multicenter Effectiveness-Implementation Study. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2020, 44, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Rincón, A.; Pérez, L.M.; Bagur-Calafat, C.; Barrios-Franquesa, A.M.; Amor-Barbosa, M.; Doménech-García, V.; Bellosta-López, P.; Buesa-Estéllez, A.; Girabent-Farrés, M. The effect of brief, repetitive balance training on balance and fall risk in older people with stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2025, 39, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, L.; Collino, F.; Marzi, A.; Pellegrino, L.; Ponzano, M.; Chiaro, D.D.; Maestrini, S.; Caneva, S.; Pardini, M.; Fiaschi, P.; et al. Useful outcome measures in INPH patients evaluation. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1201932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.M.; Simieli, L.; Bersotti, F.M.; Mochizuki, L.; Barbieri, F.A.; Coelho, D.B. Gait and posture are correlated domains in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 775, 136537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, A.; Hortobágyi, T.; Beurskens, R.; Granacher, U. Effects of Supervised vs. Unsupervised Training Programs on Balance and Muscle Strength in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2341–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusi, N.; Carmelo Adsuar, J.; Corzo, H.; Del Pozo-Cruz, B.; Olivares, P.R.; Parraca, J.A. Balance training reduces fear of falling and improves dynamic balance and isometric strength in institutionalised older people: A randomised trial. J. Physiother. 2012, 58, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Session: Resistance Training | ||

| Initial week | Final week | |

| Exercises | Sets per repetition | Sets per repetition |

| Unstable body-weight squat | 3 × 8 | 3 × 10 |

| Unstable body-weight lunges | ||

| Forward lunges | 2 × 8, each leg | 3 × 10, each leg |

| Backward lunges | 2 × 8, each leg | 3 × 10, each leg |

| Lateral right lunges | 2 × 8, right leg | 3 × 10, right leg |

| Lateral left lunges | 2 × 8, left leg | 3 × 10, left leg |

| Single-leg step-ups | 2 × 8, each leg | 3 × 10, each leg |

| Elastic bands strengthening exercises for tibialis anterior, soleus, and peroneal muscles | 3 × 8 each exercise to perform as a circuit | 4 × 10 each exercise to perform as a circuit |

| Second session: balance and proprioception training | ||

| Exercises | Sets per repetition or time duration | Sets per repetition or time duration |

| Single-leg balance with object reaching | 4 × 15 s, each leg | 5 × 30 s, each leg |

| Unstable single-leg balance | 3 × 10 s of position maintenance, each leg | 4 × 15 s of position maintenance, each leg |

| Unstable bilateral balance exercise | 4 × 10 s of position maintenance | 5 × 15 s of position maintenance |

| Unstable bilateral balance with eyes closed | 3 × 10 s of position maintenance | 4 × 15 s of position maintenance |

| Unstable bilateral balance while bouncing a ball against a wall | 3 × 10 of bouncing a ball | 4 × 15 of bouncing a ball |

| Third session: motor–cognitive training | ||

| Exercises | Sets per repetition or time duration | Sets per repetition or time duration |

| Unstable body-weight squat | 2 × 8 | 2 × 10 |

| Unstable body-weight lunges | ||

| Forward lunges | 1 × 8, each leg | 2 × 10, each leg |

| Backward lunges | 1 × 8, each leg | 2 × 10, each leg |

| Lateral right lunges | 1 × 8, right leg | 1 × 10, right leg |

| Lateral left lunges | 1 × 8, left leg | 1 × 10, left leg |

| Single-leg step-ups | 2 × 8, each leg | 2 × 10, each leg |

| Single-leg balance with object reaching * | 2 × 20 s, each leg | 3 × 30 s, each leg |

| Unstable single-leg balance * | 2 × 10 s of position maintenance, each leg | 2 × 20 s of position maintenance, each leg |

| Unstable bilateral balance exercise * | 2 × 10 s of position maintenance | 3 × 10 s of position maintenance |

| Unstable bilateral balance with eyes closed * | 1 × 10 s of position maintenance | 2 × 15 s of position maintenance |

| Unstable bilateral balance while bouncing a ball against a wall * | 1 × 10 of bouncing a ball | 2 × 15 of bouncing a ball |

| Balance Related and TWSTRS Assessments | Pre-Training Values | Post-Training Values | Absolute Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-BEST (score) | 19 | 28 | +9 |

| FSST (s) | 6.92 | 5.84 | −1.08 |

| FES-I (score) | 30 | 21 | −9 |

| TWSTRS total (score) | 33 | 29 | −4 |

| TWSTRS part 2 (score) | 10 | 6 | −4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crisafulli, O.; Sarrocco, M.; Fortunati, M.; Serra, M.; Quintiero, V.; D’Antona, G. Balance, Gait Kinematics, and Fear of Falling After a Four-Month Targeted Training Program in a Patient with Cervical Dystonia: A Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121831

Crisafulli O, Sarrocco M, Fortunati M, Serra M, Quintiero V, D’Antona G. Balance, Gait Kinematics, and Fear of Falling After a Four-Month Targeted Training Program in a Patient with Cervical Dystonia: A Case Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121831

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrisafulli, Oscar, Marta Sarrocco, Matteo Fortunati, Marco Serra, Venere Quintiero, and Giuseppe D’Antona. 2025. "Balance, Gait Kinematics, and Fear of Falling After a Four-Month Targeted Training Program in a Patient with Cervical Dystonia: A Case Report" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121831

APA StyleCrisafulli, O., Sarrocco, M., Fortunati, M., Serra, M., Quintiero, V., & D’Antona, G. (2025). Balance, Gait Kinematics, and Fear of Falling After a Four-Month Targeted Training Program in a Patient with Cervical Dystonia: A Case Report. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121831