Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Association with Mental Health Symptomatology Among Latvian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

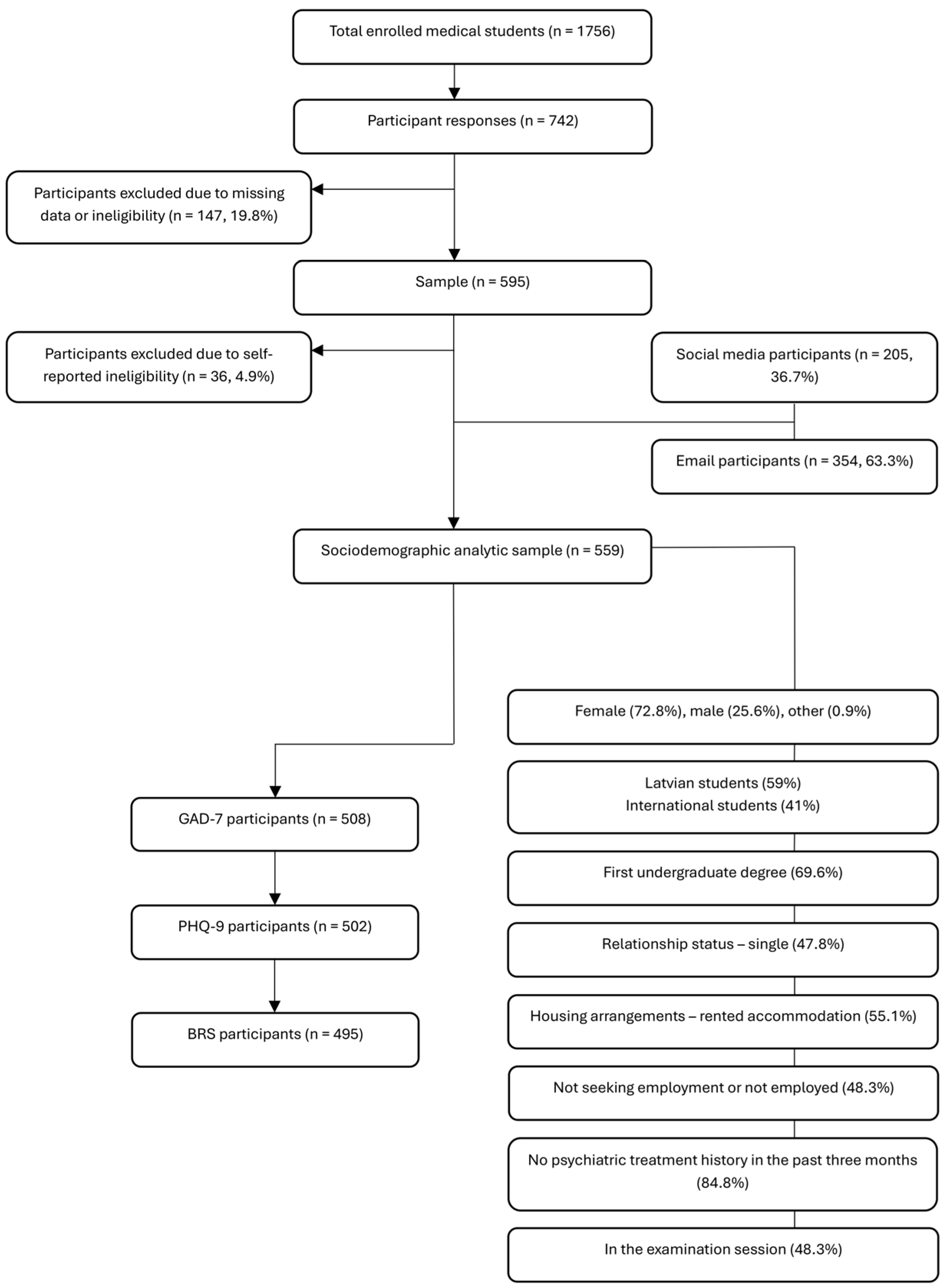

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Ethics and Ethical Considerations

2.4. Measurement Tools and Procedures

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.1.1. Measurement Instruments (PHQ-9, GAD-7, BRS) and Their Trends

3.1.2. Sociodemographic Factors and PHQ-9 Scores

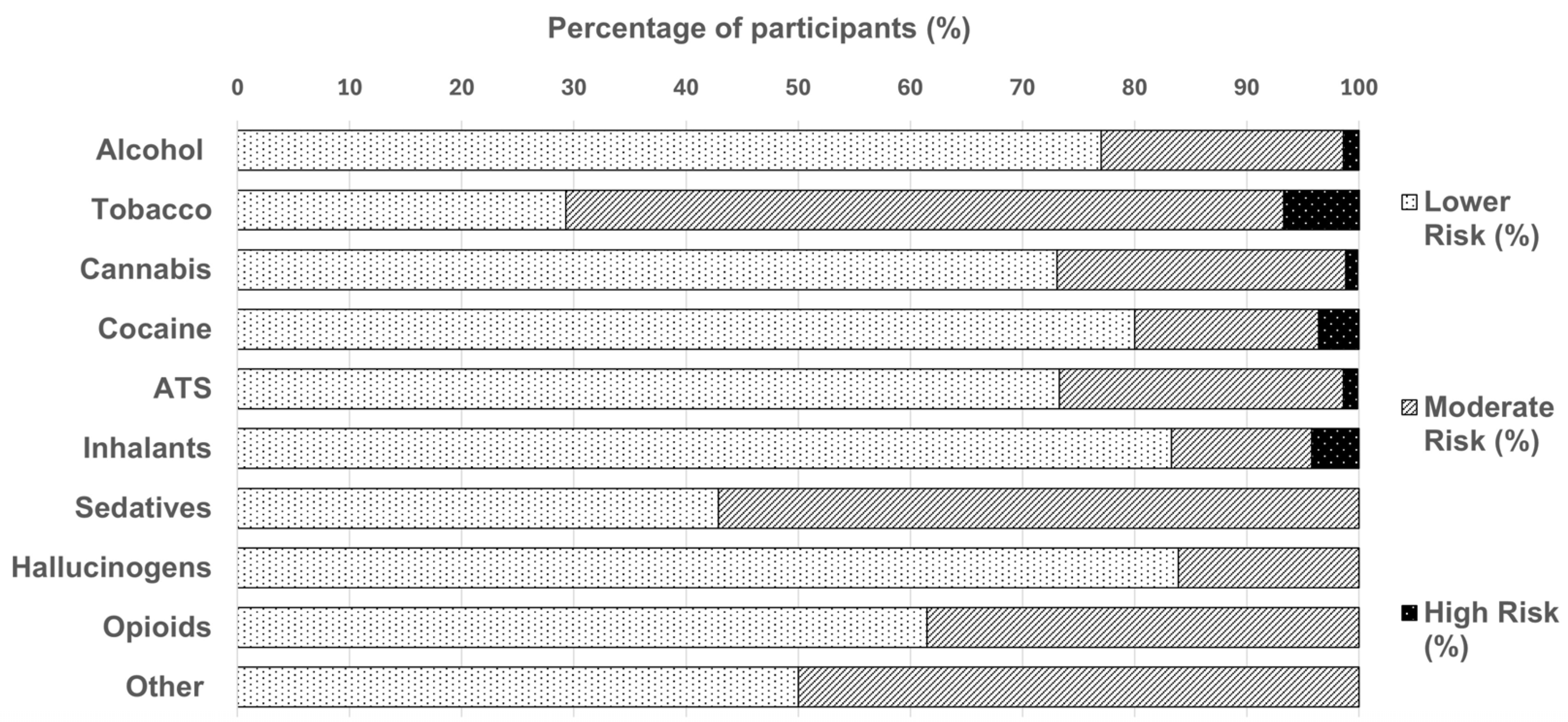

3.2. WHO ASSIST Substance Use Trends

Substance Use and WHO ASSIST Risk Grouping

3.3. Additional Findings and Miscellaneous Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Substance Use Trends

4.2. Associations Between Demographics and Depression, Anxiety, and Resilience Scores

4.3. Year-of-Study Differences in Depression, Anxiety, and Resilience

4.4. Associations Between Mental Health, Socio-Demographics, and Substance Use Risk

4.5. Implications and Recommendations

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO ASSIST | World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test |

| GAD-7 | The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 |

| PHQ-9 | The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 |

| BRS | The Brief Resilience Scale |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Question 1: In Your Life, Which of the Following Substances Have You Ever Used? | |||||

| Examples (pharmacological/brand names as in the original) | No | Yes | |||

| Caffeine | Coffee, tea, energy drinks, etc. | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Question 1.1: Please answer the following substances, if you have used them as medicine prescribed by a doctor/doctor’s prescription. | |||||

| Antidepressants | Fluoxetine/Prozac, Paroxetine/Paxil, Sertraline/Zoloft, Escitalopram/Cipralex/Lexapro, Trazadone/Desyrel/Oleptro, Bupropion/Wellbutrin/Zyban, etc. | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Anxiolytics | Alprazolam/Xanax/Niravam, Gabazolamine, Diazepam/Valium, Lorazepam/Ativan, etc. | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Medicinal stimulants | Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine/Adderall, Methylphenidate/Concerta,/Ritalin, etc. | ☐ | ☐ | ||

| Other (specify): | ☐ | ☐ | |||

| Question 2: In the past three months, how often have you used the substances you mentioned (first drug, second drug, etc.)? | |||||

| Category | Never | Once or twice | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily |

| Caffeine (coffee, tea, energy drinks, etc.) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Antidepressants (Fluoxetine/Prozac, Paroxetine/Paxil, Sertraline/Zoloft, Escitalopram/Cipralex/Lexapro, Trazadone/Desyrel/Oleptro, Bupropion/Wellbutrin/Zyban, etc.) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Anxiolytics (Alprazolam/Xanax/Niravam, Gabazolamine, Diazepam/Valium, Lorazepam/Ativan, etc.) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Medicinal stimulants (Amphetamine/Dextroamphetamine/Adderall, Methylphenidate/Concerta/Ritalin, etc.) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Other (specify): | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

Appendix A.2

| Predictor | Wald χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 572.458 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 10.468 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Living quarters | 5.099 | 2 | 0.078 |

| Student origin | 3.085 | 1 | 0.079 |

| PHQ-9 total score | 3.458 | 1 | 0.063 |

| GAD-7 total score | 2.149 | 1 | 0.143 |

| Clinical year | 0.316 | 1 | 0.574 |

| Predictor | B | SE | 95% CI for B | Wald χ2 | p | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.692 | 0.165 | [2.369–3.015] | 266.545 | <0.001 | 14.77 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | −0.394 | 0.122 | [−0.633–−0.155] | 10.468 | 0.001 | 0.674 |

| Living quarters (owned vs. family) | 0.140 | 0.170 | [−0.194–0.473] | 0.676 | 0.411 | 1.150 |

| Living quarters (rented vs. family) | 0.310 | 0.137 | [0.041–0.579] | 5.099 | 0.024 | 1.364 |

| Student origin (international vs. Latvian) | −0.241 | 0.137 | [−0.510–0.028] | 3.085 | 0.079 | 0.786 |

| PHQ-9 total score | 0.020 | 0.016 | [−0.001–0.041] | 3.458 | 0.063 | 1.020 |

| GAD-7 total score | 0.019 | 0.013 | [−0.006–0.044] | 2.149 | 0.143 | 1.019 |

| Clinical year (pre-clinical vs. clinical) | 0.061 | 0.108 | [−0.152–0.274] | 0.316 | 0.574 | 1.063 |

References

- Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Guillén, V.; Irigoyen-Otiñano, M.; Balanzá-Martínez, V. Screening of substance use and mental health problems among Spanish medical students: A multicenter study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, E.; Faubl, N.; Riemenschneider, H.; Balázs, P.; Bergmann, A.; Cseh, K.; Horváth, F.; Schelling, J.; Terebessy, A.; Wagner, Z.; et al. Cigarette, waterpipe and e-cigarette use among an international sample of medical students. Cross-sectional multicenter study in Germany and Hungary. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajda, M.; Sedlaczek, K.; Szemik, S.; Kowalska, M. Determinants of Alcohol Consumption among Medical Students: Results from POLLEK Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaume, J.; Carrard, V.; Berney, S.; Bourquin, C.; Berney, A. Substance use and its association with mental health among Swiss medical students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignon, M.; Havet, E.; Ammirati, C.; Traullé, S.; Manaouil, C.; Balcaen, T.; Loas, G.; Dubois, G.; Ganry, O. Alcohol, Cigarette, and Illegal Substance Consumption Among Medical Students. Workplace Health Saf. 2015, 63, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song-Smith, C.; Jacobs, E.; Rucker, J.; Saint, M.; Cooke, J.; Schlosser, M. UK medical students’ self-reported knowledge and harm assessment of psychedelics and their application in clinical research: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullian, B.; Deltour, M.; Franchitto, N. The consumption of psychoactive substances among French physicians: How do they perceive the creation of a dedicated healthcare system? Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1249434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, S.J.; Henderson, M.N.; Prenner, S.; Grauer, J.N. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among Medical Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2021, 8, 2382120521991150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-K.; Saragih, I.D.; Lin, C.-J.; Liu, H.-L.; Chen, C.-W.; Yeh, Y.-S. Global prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B.; Nieblas-Bedolla, E.; Gordon-Elliott, J.S.; Kang, Y.; Holcomb, K.; Frey, M.K. Mental Health of US Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3295–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempski, P.; Arantes-Costa, F.M.; Kobayasi, R.; Siqueira, M.A.M.; Torsani, M.B.; Amaro, B.Q.R.C.; Nascimento, M.E.F.M.; Siqueira, S.L.; Santos, I.S.; Martins, M.A. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, T.T.-C.; Tam, W.W.-S.; Tran, B.X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ho, C.S.-H.; Ho, R.C.-M. The Global Prevalence of Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, S.R.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Roslan, N.S. Mapping the multidimensional factors of medical student resilience development: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, D.; Suponcic, S.J.; Chen, N.; Steinhart, C.; Duong, P. Prevalence of Generalized Anxiety Disorder Among Five European Countries Before and During COVID. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, S322–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, J.A.-D.; Vilagut, G.; Ronaldson, A.; Bakolis, I.; Dregan, A.; Martín, V.; Martinez-Alés, G.; Molina, A.J.; Serrano-Blanco, A.; Valderas, J.M.; et al. Prevalence and variability of depressive symptoms in Europe: Update using representative data from the second and third waves of the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS-2 and EHIS-3). Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e889–e898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, T.; Chamanadjian, C.; Nguyen, H. Substance Misuse Among Medical Students, Resident Physicians, and Fellow Physicians: A Review with Focus on the United States’ Population. Cureus 2024, 16, e72636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, E.E.; Roseman, D.; Winseman, J.S.; Mason, H.R.C. Prevalence, perceptions, and consequences of substance use in medical students. Med. Educ. Online 2017, 22, 1392824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncero, C.; Egido, A.; Rodríguez-Cintas, L.; Pérez-Pazos, J.; Collazos, F.; Casas, M. Substance Use among Medical Students: A Literature Review 1988–2013. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2015, 43, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Papazisis, G.; Siafis, S.; Tsakiridis, I.; Koulas, I.; Dagklis, T.; Kouvelas, D. Prevalence of Cannabis Use Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Subst Abuse 2018, 12, 1178221818805977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinoff, A.N.; Nix, C.A.; McNeil, S.E.; Wagner, S.E.; Johnson, C.A.; Williams, B.C.; Cornett, E.M.; Murnane, K.S.; Kaye, A.M.; Kaye, A.D. Prescription Stimulants in College and Medical Students: A Narrative Review of Misuse, Cognitive Impact, and Adverse Effects. Psychiatry Int. 2022, 3, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumber, N.; Majeed, M.; Ziff, S.; Thomas, S.E.; Bolla, S.R.; Gorantla, V.R. Stimulant Usage by Medical Students for Cognitive Enhancement: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e15163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, D.C.; Wilson, D.B. Characteristics of Effective School-Based Substance Abuse Prevention. Prev. Sci. 2003, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.L.; Becker, L.G.; Huber, A.M.; Catalano, R.F. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 747–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbach, J.T.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Bagwell, M.; Dunlap, S. Minority Stress and Substance Use in Sexual Minority Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Prev. Sci. 2014, 15, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Jersovs, K.; Safina, T.; Pilmane, M.; Jansone-Ratinika, N.; Grike, I.; Petersons, A. Medical education in Latvia: An overview of current practices and systems. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1250138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Which Countries Have the Most Doctor and Dentist Graduates? Website: News Article. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20240805-1 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- University, R.S. Medicine 3.0 Study Programme—A New Era in Latvian Medical Education. Riga Stradins University. Available online: https://www.rsu.lv/en/news/medicine-30-study-programme-new-era-latvian-medical-education (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Rueckert, K.-K.; Ancane, G. Cross-sectional study among medical students in Latvia: Differences of mental symptoms and somatic symptoms among Latvian and international students. Pap. Anthropol. 2018, 27, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Martino, R.J.; LoSchiavo, C.; Comer-Carruthers, C.; Krause, K.D.; Stults, C.B.; Halkitis, P.N. Ensuring survey research data integrity in the era of internet bots. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 2841–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, F.J.; Leslie, G.D.; Grech, C.; Latour, J.M. Using a web-based survey tool to undertake a Delphi study: Application for nurse education research. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humeniuk, R.; Ali, R.; Babor, T.F.; Farrell, M.; Formigoni, M.L.; Jittiwutikarn, J.; De Lacerda, R.B.; Ling, W.; Marsden, J.; Monteiro, M.; et al. Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008, 103, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humeniuk, R.; Ali, R.; Poznyak, V.; Monteiro, M. The Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for Use in Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, J.; Strauss, S.M.; Rotrosen, J.; Ramautar, A.; Gourevitch, M.N. Validation of an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) version of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Addiction 2016, 111, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, S.; Glenn, T. Searching online to buy commonly prescribed psychiatric drugs. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 260, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papazisis, G.; Tsakiridis, I.; Siafis, S. Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs among Medical Students and the Relationship With Illicit Drug, Tobacco, and Alcohol Use. Subst. Abus. 2018, 12, 1178221818802298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garakani, A.; Murrough, J.W.; Freire, R.C.; Thom, R.P.; Larkin, K.; Buono, F.D.; Iosifescu, D.V. Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 595584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, S.; Vickers-Smith, R.; Guirguis, A.; Corkery, J.M.; Martinotti, G.; Schifano, F. A Focus on Abuse/Misuse and Withdrawal Issues with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Analysis of Both the European EMA and the US FAERS Pharmacovigilance Databases. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiolini, A.; Grošelj, L.D.; Šagud, M.; Silić, A.; Latas, M.; Miljević, Č.D.; Cuomo, A. Targeting heterogeneous depression with trazodone prolonged release: From neuropharmacology to clinical application. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2025, 24, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callovini, T.; Janiri, D.; Segatori, D.; Mastroeni, G.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Di Nicola, M.; Sani, G. Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbe, M.; Sawchik, J.; Gräfe, M.; Wuillaume, F.; De Bruyn, S.; Van Antwerpen, P.; Van Hal, G.; Desseilles, M.; Hamdani, J.; Malonne, H. Use and misuse of prescription stimulants by university students: A cross-sectional survey in the French-speaking community of Belgium, 2018. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalese, M.; Baroni, M.; Biagioni, S.; Bastiani, L.; Denoth, F.; Molinaro, S. Exploring changes in non-medical prescription use of pharmaceutical stimulants among Italian adolescents from 2008 to 2023. J. Public Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikoff, D.; Welsh, B.T.; Henderson, R.; Brorby, G.P.; Britt, J.; Myers, E.; Goldberger, J.; Lieberman, H.R.; O‘BRien, C.; Peck, J.; et al. Systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine consumption in healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents, and children. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 585–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, J.L.; Bernard, C.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Czachor, J.D.; Westphal, J.A.; Mestre, M.A. The Safety of Ingested Caffeine: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, M.; Abdoli, F.; Momeni, F.; Asgarabad, M.H. Network analysis of caffeine use disorder, withdrawal symptoms, and psychiatric symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.M.; Weaver, D.C.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M.; Griffiths, R.R. Prevalence and Correlates of Caffeine Use Disorder Symptoms Among a United States Sample. J. Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2020, 10, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Estrada-Hernández, N.; Booth, J.; Pan, D. Factor structure, internal reliability, and construct validity of the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS): A study on persons with serious mental illness living in the community. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 94, 620–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancans, E.; Trapencieris, M.; Ivanovs, R.; Vrublevska, J. Validity of the PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 to screen for depression in nationwide primary care population in Latvia. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrublevska, J.; Renemane, L.; Kivite-Urtane, A.; Rancans, E. Validation of the generalized anxiety disorder scales (GAD-7 and GAD-2) in primary care settings in Latvia. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 972628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W. The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)—Originally by B. W. Smith (2008), Adapted by G. Freimane as Īsā Dzīvesspēka Skala (2010), Obtained from RSU Psychology Laboratory’s Registry of Tests and Surveys. 2008. Available online: https://www.rsu.lv/en/psychology-laboratory/test-and-survey-registry (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Kjellsson, G.; Clarke, P.; Gerdtham, U.-G. Forgetting to remember or remembering to forget: A study of the recall period length in health care survey questions. J. Health Econ. 2014, 35, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner-Hofbauer, V.; Katz, H.W.; Grundnig, J.S.; Holzinger, A. Female participation or ‘feminization’ of medicine. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2023, 173, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabkowski, P.; Piekut, A. Between task complexity and question sensitivity: Nonresponse to the income question in the 2008–2018 European Social Survey. Surv. Res. Methods 2024, 18, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groene, O.R.; Huelmann, T.; Hampe, W.; Emami, P. German Physicians and Medical Students Do Not Represent the Population They Serve. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, S.; Tiffin, P.A.; Greatrix, R.; Lee, A.J.; Patterson, F.; Nicholson, S.; Cleland, J. Do changing medical admissions practices in the UK impact on who is admitted? An interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, K.; Dowell, J.; Jackson, C.; Guthrie, B. Fair access to medicine? Retrospective analysis of UK medical schools application data 2009-2012 using three measures of socioeconomic status. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, L.; Wouters, A.; Akwiwu, E.U.; Koster, A.S.; Ravesloot, J.H.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Salih, M.; Croiset, G.; Kusurkar, R.A. Diversity in the pathway from medical student to specialist in the Netherlands: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2023, 35, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muselli, M.; Tobia, L.; Cimino, E.; Confalone, C.; Mancinelli, M.; Fabiani, L.; Necozione, S.; Cofini, V. COVID-19 Impact on Substance Use (Tobacco, Alcohol, Cannabis) and Stress in Medical Students. OBM Neurobiol. 2024, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pighi, M.; Pontoni, G.; Sinisi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Mattei, G.; Pingani, L.; Simoni, E.; Galeazzi, G.M. Use and Propensity to Use Substances as Cognitive Enhancers in Italian Medical Students. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, M.; Napolitano, F.; Napolitano, P.; Arnese, A.; Crispino, V.; Panariello, G.; Di Giuseppe, G. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among under- and post-graduate healthcare students in Italy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbon, A.; Boyer, L.; Auquier, P.; Boucekine, M.; Barrow, V.; Lançon, C.; Fond, G. Anxiolytic consumption is associated with tobacco smoking and severe nicotine dependence. Results from the national French medical students (BOURBON) study. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 94, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Bourbon, A.; Lançon, C.; Boucekine, M.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Auquier, P.; Boyer, L. Psychiatric and psychological follow-up of undergraduate and postgraduate medical students: Prevalence and associated factors. Results from the national BOURBON study. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengvenytė, A.; Strumila, R. Do medical students use cognitive enhancers to study? Prevalence and correlates from lithuanian medical students sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 33, S304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebrini, T.; Manz, K.; Koller, G.; Krause, D.; Soyka, M.; Franke, A.G. Psychiatric Comorbidity and Stress in Medical Students Using Neuroenhancers. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 771126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Bourbon, A.; Boucekine, M.; Messiaen, M.; Barrow, V.; Auquier, P.; Lançon, C.; Boyer, L. First-year French medical students consume antidepressants and anxiolytics while second-years consume non-medical drugs. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner-Hofbauer, V.; Holzinger, A. How to Cope with the Challenges of Medical Education? Stress, Depression, and Coping in Undergraduate Medical Students. Acad. Psychiatry 2020, 44, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberstadt, A.L. Recent advances in the neuropsychopharmacology of serotonergic hallucinogens. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 277, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, A.; Sander, D.; Köhler, T.; Hees, N.; Oswald, F.; Scherbaum, N.; Deimel, D.; Schecke, H. Chemsex and Mental Health of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Germany. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 542301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platteau, T.; Herrijgers, C.; Barvaux, V.; Berghe, W.V.; Apers, L.; Vanbaelen, T. Chemsex and its impact on gay and bisexual men who have sex with men: Findings from an online survey in Belgium. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandain, L.; Mosser, S.; Mouchabac, S.; Blanc, J.-V.; Alexandre, C.; Thibaut, F. Chemical sex (chemsex) in a population of French university students. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 23, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, A.; Malin, G. How medical students cope with stress: A cross-sectional look at strategies and their sociodemographic antecedents. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.A.; Baig, M.; Beyari, G.M.; Halawani, M.A.; Mirza, A.A. Depression and Anxiety Among Medical Students: A Brief Overview. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. Vol. 2021, 12, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C.; Asnaani, A.; Litz, B.T.; Hofmann, S.G. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remes, O.; Brayne, C.; van der Linde, R.; Lafortune, L. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, T.D.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, K.; Bonardi, O.; Krishnan, A.; Boruff, J.T.; et al. Systematic review of mental health symptom changes by sex or gender in early-COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckeviciene, A.; Saudargiene, A.; Gecaite-Stonciene, J.; Liaugaudaite, V.; Griskova-Bulanova, I.; Simkute, D.; Naginiene, R.; Dainauskas, L.L.; Ceidaite, G.; Burkauskas, J. Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 and the generalized anxiety disorder-7 in Lithuanian student sample. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, T.; Aluoja, A.; Vasar, V.; Veldi, M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in Estonian medical students with sleep problems. Depress. Anxiety 2006, 23, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, D.I.; Hinić, D.; Banković, D.; Kočović, A.; Ristić, I.; Rosić, G.; Ristić, B.; Milovanović, D.; Janjić, V.; Jovanović, M.; et al. Levels of stress and resilience related to the COVID-19 pandemic among academic medical staff in Serbia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 604–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersson, E.; Boman, J.; Bitar, A. Impostor phenomenon and its association with resilience in medical education—A questionnaire study among Swedish medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, K.-H. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 1716–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, K.M.; Berhanu, K.Z. Depression and substance abuse among university students. Medicine 2025, 104, e41671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foli, K.J.; Zhang, L.; Reddick, B. Predictors of Substance Use in Registered Nurses: The Role of Psychological Trauma. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, T.A.; Heller, S.; Reichel, J.L.; Werner, A.M.; Schäfer, M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Simon, P.; Beutel, M.E.; Letzel, S.; Rigotti, T.; et al. Cigarette Smoking, Risky Alcohol Consumption, and Marijuana Smoking among University Students in Germany: Identification of Potential Sociodemographic and Study-Related Risk Groups and Predictors of Consumption. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Guidelines for the Development of Chemical Impairment Policies for Medical Schools. AAMC: Leading. Serving. Advocating. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/learn-network/affinity-groups/gsa/chemical-guide (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Mannes, Z.; Wang, T.L.; Ma, W.; Selzer, J.; Blanco, C. Student Substance Use Policies in US Allopathic Medical Schools. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Shah, N.K.; Adamczyk, A.L.; Weinstein, L.C.; Kelly, E.L. Harm reduction in undergraduate and graduate medical education: A systematic scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T.E.; Chammaa, M.; Ramos, R.; Waineo, E.; Greenwald, M.K. Incoming Medical Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward People with Substance use Disorders: Implications for Curricular Training. Subst. Abus. 2021, 42, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahji, A.; Danilewitz, M.; Guerin, E.; Maser, B.; Frank, E. Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Substance Use Among Canadian Medical Students. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2133994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhaibani, R.; Smith, D.C.; Lowrie, R.; Aljhani, S.; Paudyal, V. Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachini, A.; Aliane, P.P.; Martinez, E.Z.; Furtado, E.F. Efficacy of brief alcohol screening intervention for college students (BASICS): A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2012, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RSU Career Guidance and Wellbeing Centre. Career Guidance and Wellbeing Centre. RSU: Career Guidance and Wellbeing Centre. Available online: https://www.rsu.lv/en/career-guidance-and-wellbeing-centre (accessed on 5 November 2025).

| Variables | Categories | M ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 22.3 ± 4.1 | |

| n (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 143 (25.6) |

| Female | 407 (72.8) | |

| Other | 5 (0.9) | |

| No response | 4 (0.7) | |

| Student origin | International students | 229 (41.0) |

| Latvian students | 330 (59.0) | |

| International student nationality * | German | 64 (27.9) |

| Swedish | 36 (15.7) | |

| Finnish | 23 (10.0) | |

| Italian | 22 (9.6) | |

| Russian | 22 (9.6) | |

| All other nationalities | 62 (27.0) | |

| Academic year | 1 | 243 (43.5) |

| 2 | 60 (10.7) | |

| 3 | 72 (12.9) | |

| 4 | 47 (8.4) | |

| 5 | 81 (14.5) | |

| 6 | 49 (8.8) | |

| No response | 7 (1.3) | |

| Prior education | Attending university but no degree | 389 (69.6) |

| Associate’s degree | 19 (3.4) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 47 (8.4) | |

| Graduate degree | 69 (12.3) | |

| No response | 35 (6.3) | |

| Marital status | Single | 267 (47.8) |

| In a committed relationship | 250 (44.7) | |

| Married | 26 (4.7) | |

| Separated or widowed | 12 (2.1) | |

| No response | 4 (0.7) | |

| Housing arrangements | Owned | 58 (10.4) |

| Rented | 308 (55.1) | |

| Live with family or partner | 186 (33.3) | |

| No response | 7 (1.3) | |

| Employment status | Employed > 160 h—full-time | 29 (5.2) |

| Employed < 160 h—part-time | 185 (33.1) | |

| Not employed, looking for work | 65 (11.6) | |

| Not employed, not looking for work | 270 (48.3) | |

| No response | 10 (1.8) | |

| Any applicable psychiatric treatment | Pharmacotherapy | 35 (6.3) |

| Psychotherapy | 58 (10.4) | |

| Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy | 63 (11.3) | |

| Brain stimulation therapy | 1 (0.2) | |

| All other combinations | 3 (0.5) | |

| None | 384 (68.7) | |

| No response | 15 (2.7) | |

| Psychiatric treatment in the last 90 days | Yes | 76 (13.6) |

| No | 474 (84.8) | |

| No response | 9 (1.6) | |

| Children | None | 518 (92.7) |

| One or More | 33 (5.9) | |

| No response | 8 (1.4) | |

| Examination status | In the exam session | 270 (48.3) |

| Not in the exam session | 278 (49.7) | |

| No response | 11 (2.0) | |

| Total monthly income earned by all members of the household, excluding grants and loans | EUR 0–1000 | 105 (18.8) |

| EUR 1001–2000 | 88 (15.7) | |

| EUR 2001–5000 | 135 (24.2) | |

| EUR 5001–10,000 | 45 (8.1) | |

| EUR 10,001–20,000 | 25 (4.5) | |

| EUR 20,001 or more | 27 (4.8) | |

| I do not wish to answer | 127 (22.7) | |

| No response | 7 (1.3) |

| Instrument | Total Sample | Female | Male | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous scores | |||||

| BRS | 3.25 ± 0.88 (n = 495) | 3.10 ± 0.82 (n = 361) | 3.69 ± 0.92 (n = 127) | t(201.9) = −6.34; MD = −0.59, 95% CI [−0.77–−0.40] | p < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 | 10.0 [5.0–15.0] (n = 508) | 11.0 [7.0–15.0] (n = 371) | 5.0 [3.0–11.0] (n = 130) | U = 14,495.50; HL = 4.0, 95% CI [3.0–6.0] | p < 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 | 9.0 [4.8–15.0] (n = 502) | 10.0 [5.0–15.5] (n = 365) | 6.0 [3.0–13.0] (n = 130) | U = 17,429.50; HL = 3.0, 95% CI [2.0–4.0] | p < 0.001 |

| Categorical classifications | |||||

| BRS categories | (n = 495) | (n = 361) | (n = 127) | ||

| Low resilience (1.00–2.99) | 185 (37.4%) | 151 (41.8%) | 29 (22.8%) | χ2(2) = 48.87 | p < 0.001 |

| Normal resilience (3.00–4.30) | 238 (48.1%) | 180 (49.9%) | 56 (44.1%) | ||

| High resilience (4.31–5.00) | 72 (14.5%) | 30 (8.3%) | 42 (33.1%) | ||

| GAD-7 Scores | (n = 508) | (n = 371) | (n = 130) | ||

| None to minimal (0–4) | 113 (22.2%) | 56 (15.1%) | 57 (43.8%) | χ2(3) = 53.82 | p < 0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 136 (26.8%) | 97 (26.1%) | 37 (28.5%) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 124 (24.4%) | 106 (28.6%) | 17 (13.1%) | ||

| Severe (15–21) | 135 (26.6%) | 112 (30.2%) | 19 (14.6%) | ||

| PHQ-9 Scores | (n = 502) | (n = 365) | (n = 130) | ||

| None or minimal (0–4) | 125 (24.9%) | 69 (18.9%) | 55 (42.3%) | χ2(4) = 31.23 | p < 0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 138 (27.5%) | 102 (27.9%) | 33 (25.4%) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 110 (21.9%) | 93 (25.5%) | 17 (13.1%) | ||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 63 (12.5%) | 51 (14.0%) | 10 (7.7%) | ||

| Severe (20–27) | 66 (13.1%) | 50 (13.7%) | 15 (11.5%) | ||

| Instrument | Total Sample | International Students | Latvian Students | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous scores | |||||

| BRS | 3.25 ± 0.88 (n = 495) | 3.54 ± 0.87 (n = 208) | 3.03 ± 0.83 (n = 285) | t(432.2) = −6.45; MD = −0.50, 95% CI [−0.66–−0.35] | p < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 | 10.0 [5.0–15.0] (n = 508) | 7.0 [4.0–12.5] (n = 211) | 11.0 [7.0–15.0] (n = 295) | U = 39,130.00; HL = −3.0, 95% CI [−4.0–−2.0] | p < 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 | 9.0 [4.8–15.0] (n = 502) | 7.0 [3.0–12.0] (n = 209) | 11.0 [6.0–16.0] (n = 291) | U = 39,321.50; HL = −3.0, 95% CI [−5.0–−2.0] | p < 0.001 |

| Categorical classifications | |||||

| BRS categories | (n = 495) | (n = 208) | (n = 285) | ||

| Low resilience (1.00–2.99) | 185 (37.4%) | 54 (26.0%) | 130 (45.6%) | χ2(2) = 32.63 | p < 0.001 |

| Normal resilience (3.00–4.30) | 238 (48.1%) | 105 (50.5%) | 132 (46.3%) | ||

| High resilience (4.31–5.00) | 72 (14.5%) | 49 (23.6%) | 23 (8.1%) | ||

| GAD-7 Scores | (n = 508) | (n = 211) | (n = 295) | ||

| None to minimal (0–4) | 113 (22.2%) | 71 (33.6%) | 42 (14.2%) | χ2(3) = 28.64 | p < 0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 136 (26.8%) | 53 (25.1%) | 82 (27.8%) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 124 (24.4%) | 45 (21.3%) | 78 (26.4%) | ||

| Severe (15–21) | 135 (26.6%) | 42 (19.9%) | 93 (31.5%) | ||

| PHQ-9 Scores | (n = 502) | (n = 209) | (n = 291) | ||

| None or minimal (0–4) | 125 (24.9%) | 80 (38.3%) | 45 (15.5%) | χ2(4) = 38.41 | p < 0.001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 138 (27.5%) | 56 (26.8%) | 81 (27.8%) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 110 (21.9%) | 37 (17.7%) | 72 (24.7%) | ||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 63 (12.5%) | 17 (8.1%) | 46 (15.8%) | ||

| Severe (20–27) | 66 (13.1%) | 19 (9.1%) | 47 (16.2%) | ||

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Median [IQR] | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 total score | Clinical year | Pre-clinical: 10.0 [5.0–15.0] Clinical: 7.0 [3.0–14.0] | U = 22,695.00, HL = 2.0, 95% CI [1.0–3.0] | 0.002 |

| WHO ASSIST Psychoactive Substance | Lifetime Substance Use Prevalence, n (%) | Past-Three-Month Substance Use Prevalence, n (%) | Male Lifetime Substance Use Prevalence, n (%) | Female Lifetime Substance Use Prevalence, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 505 (93.9%) | 455 (84.6%) | 131 (95.6%) | 367 (93.1%) |

| Tobacco | 379 (68.4%) | 274 (49.5%) | 111 (78.2%) | 264 (65.3%) |

| Cannabis | 270 (50.9%) | 105 (19.8%) | 83 (62.4%) | 185 (47.4%) |

| Cocaine | 56 (10.6%) | 19 (3.6%) | 23 (17.6%) | 32 (8.2%) |

| Amphetamine-type stimulants | 73 (13.9%) | 25 (4.8%) | 34 (26.2%) | 39 (10.1%) |

| Inhalants | 24 (4.6%) | 4 (0.8%) | 14 (10.8%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| Sedatives | 73 (13.9%) | 49 (9.3%) | 19 (14.6%) | 54 (13.9%) |

| Hallucinogens | 55 (10.5%) | 23 (4.4%) | 26 (20.0%) | 29 (7.5%) |

| Opioids | 13 (2.5%) | 9 (1.7%) | 6 (4.6%) | 7 (1.8%) |

| Other | 18 (3.4%) | 12 (2.3%) | 9 (6.9%) | 9 (2.3%) |

| Any non-medical drug by injection | 3 (0.6%) | |||

| Supplementary psychoactive substances | ||||

| Caffeine | 518 (98.7%) | 509 (97.0%) | 128 (98.5%) | 383 (98.7%) |

| Antidepressants | 87 (16.8%) | 46 (8.9%) | 14 (10.8%) | 71 (18.6%) |

| Anxiolytics | 76 (14.7%) | 41 (7.9%) | 18 (13.8%) | 58 (15.3%) |

| Medical stimulants | 49 (9.5%) | 34 (6.6%) | 22 (16.9%) | 27 (7.1%) |

| Other | 21 (4.1%) | 14 (2.7%) | 5 (3.8%) | 16 (4.2%) |

| Predictor | B | SE | 95% CI for B | Wald χ2 | p | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.821 | 0.112 | [2.602–3.041] | 636.704 | <0.001 | 16.8 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | −0.299 | 0.108 | [−0.510–0.088] | 7.692 | 0.006 | 0.741 |

| PHQ-9 total score | 0.033 | 0.007 | [0.019–0.046] | 21.713 | <0.001 | 1.034 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernando, W.S.A.V.; David, A.; Cianci, N.; Sevcenko, A.; Vrublevska, J.; Rancans, E.; Renemane, L. Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Association with Mental Health Symptomatology Among Latvian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121806

Fernando WSAV, David A, Cianci N, Sevcenko A, Vrublevska J, Rancans E, Renemane L. Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Association with Mental Health Symptomatology Among Latvian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121806

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernando, Warnakulasuriya S. A. V., Aviad David, Nicolo Cianci, Anastasija Sevcenko, Jelena Vrublevska, Elmars Rancans, and Lubova Renemane. 2025. "Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Association with Mental Health Symptomatology Among Latvian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121806

APA StyleFernando, W. S. A. V., David, A., Cianci, N., Sevcenko, A., Vrublevska, J., Rancans, E., & Renemane, L. (2025). Psychoactive Substance Use and Its Association with Mental Health Symptomatology Among Latvian Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121806