Frequency, Correlates, and Symptom Severity of Eating Disorders Among College Students in Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Eating Disorders (ED) and Body Dissatisfaction (BD)

1.1.1. Global Prevalence

1.1.2. Eating Disorders in Mexico

1.1.3. Comorbidities of ED

1.1.4. Screening

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

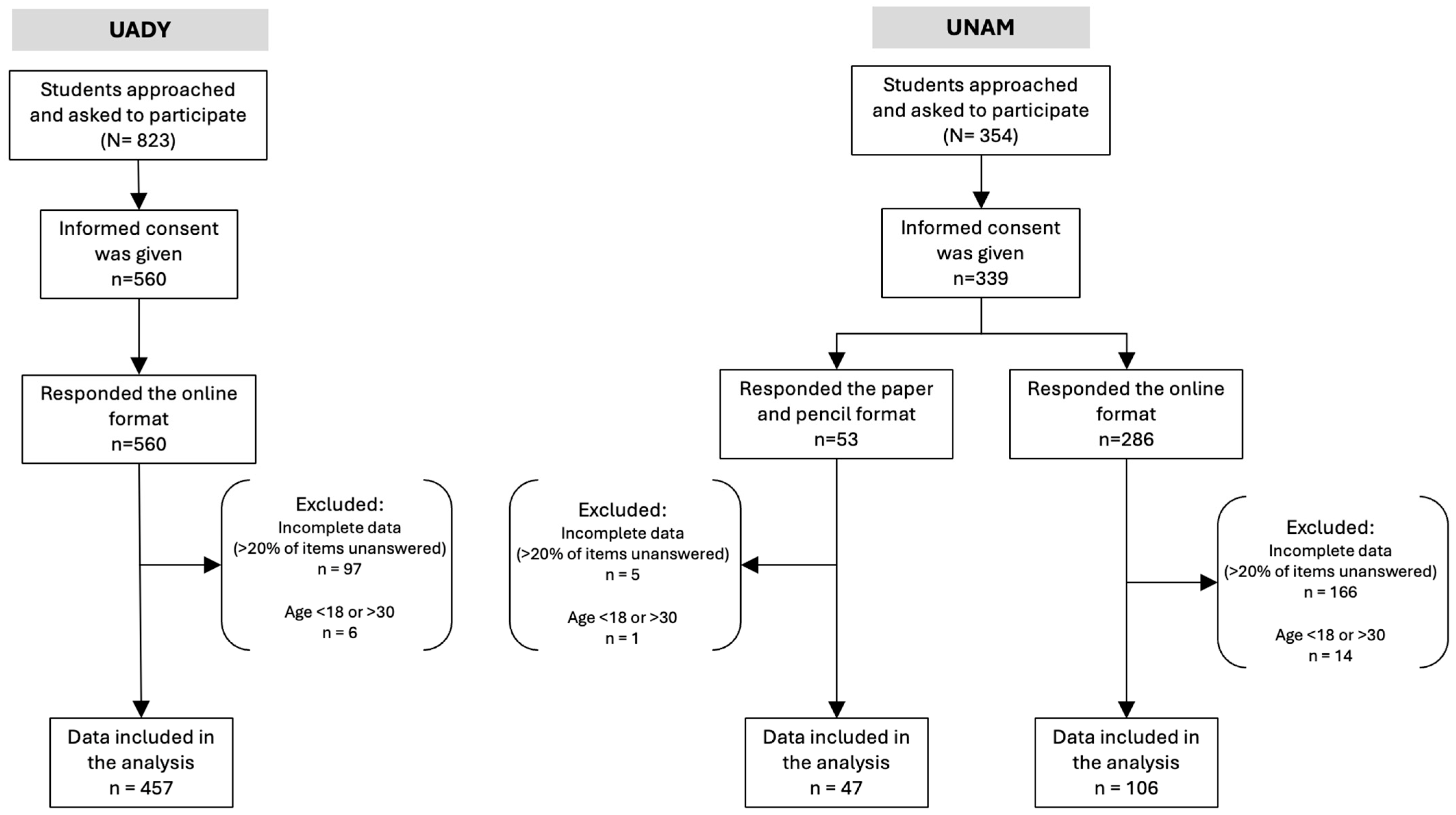

2.2. Sample

- Students attending the Faculty of Medicine at Yucatan’s Autonomous University (UADY) comprised by undergraduate students enrolled in health-related fields (nutrition and rehab medicine) who did not seek mental health services.

- Students from several disciplines enrolled at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) who sought mental health services at the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health (DPSM).

Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

2.3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

2.3.2. ED Symptomatology

2.3.3. Body Dissatisfaction (BD) by Sex

2.3.4. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

2.3.5. Alcohol Consumption

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

- A preliminary four-week period fielded in both universities included drafting and posting fact sheets on the most common ED (BN, AN and BED) and their association with the most common mental health disorders. A different ED was described in leaflets in common areas of the campus and in week four an invitation was posted throughout the campuses (UNAM and UADY) asking students to participate in a research project.

- Students enrolled in medicine and health related sciences (at Yucatan’s UADY) and those seeking mental health services (at UNAM) were recruited based on inclusion criteria (see Figure 1)

- Eligible students received a full explanation of the study and its objective, including the association between ED and mental health. Informed consent was obtained.

- After signing informed consent, students completed five screening tools: all participants completed the EAT-26, BES, AUDIT, and HADS; females additionally completed the BSQ, and males the DMS. Participants were accompanied by a member of the study team who was available to address queries and ensure proper completion of the study instruments.

- A digital version of all screening instruments as well as paper pencil surveys were used for students who did not have good internet access or preferred this format.

- Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected: age, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, major (medicine, health related sciences and others), symptoms of anxiety or depression, alcohol consumption patterns, symptoms of BD and ED symptomatology.

- After completing the instruments, which were fielded at UADY and then stored at UNAM’S central database, we analyzed the responses of all six screening tools. Paper and pencil surveys mostly fielded at UNAM were entered in the central database that included UADY and UNAM students.

- Participants who requested their results received them via email.

- All data was stored for analysis and was accessible only to members of the research team. Students were assigned alphanumeric codes to ensure anonymity.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Screening Surveys

3.2.1. Significant ED Symptomatology

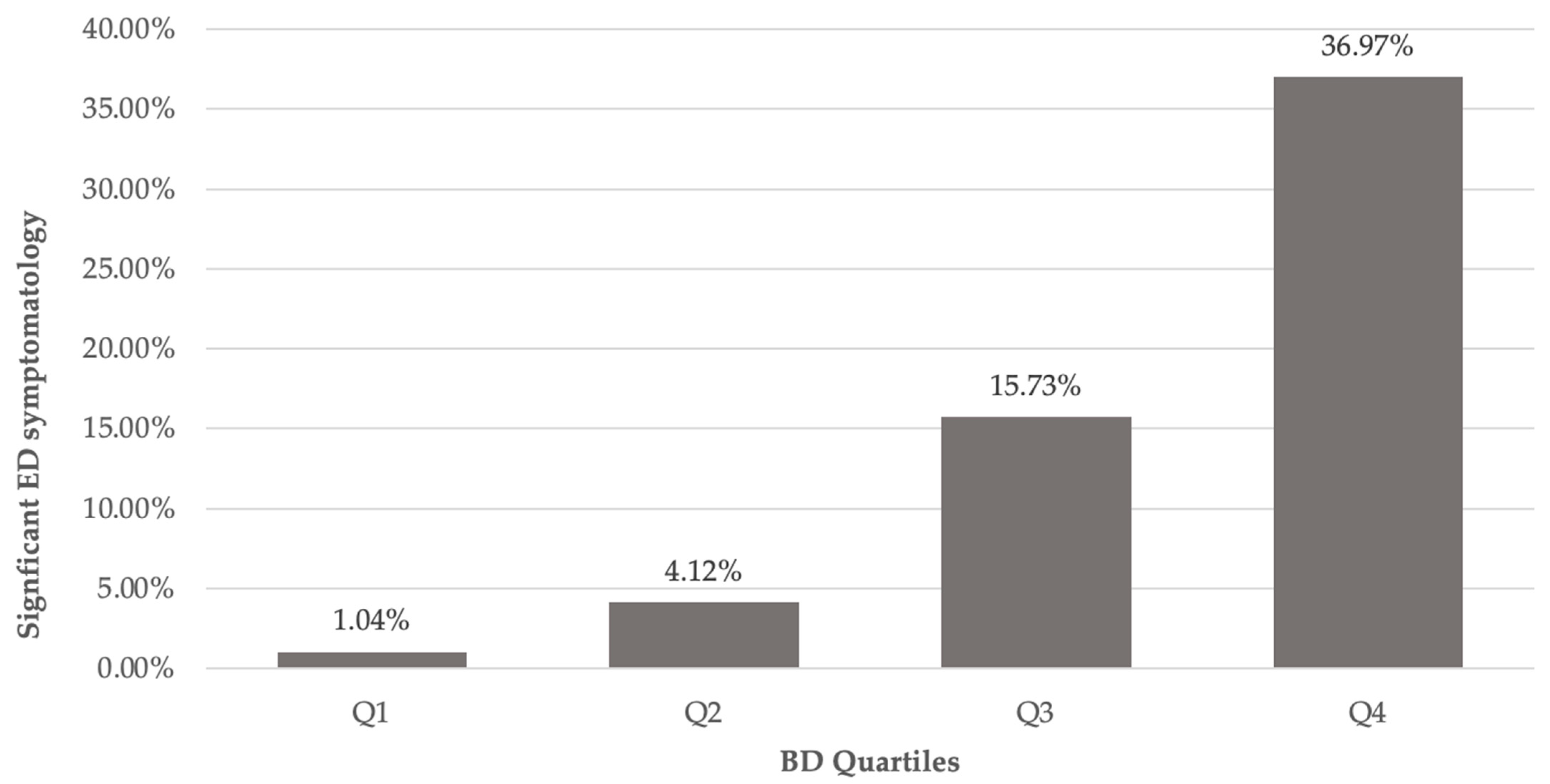

3.2.2. Symptoms of BD

3.2.3. Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

3.2.4. Alcohol Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AN | Anorexia Nervosa |

| AUDIT | Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

| BED | Binge Eating Disorder |

| BES | Binge Eating Scale |

| BD | Body Dissatisfaction |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BN | Bulimia Nervosa |

| BSQ | Body Shape Questionnaire |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DMS | Drive for Muscularity Scale |

| DPSM | Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health |

| DSM-V | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| EAT-26 | Eating Attitudes Test—26 Items |

| ED | Eating Disorders |

| ENSANUT | Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición |

| F.E.S. | Facultad de Estudios Superiores |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| IBM | International Business Machines Corporation |

| IMSS | Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía |

| LGBT | Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| REB | Risky Eating Behaviors |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| UADY | Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán |

| UNAM | Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Álvarez-Mon, M.A.; Mora, F.; Rodríguez-Quiroga, A.; Quintero, J. Actualización Sobre Los Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria. Med.—Programa Form. Médica Contin. Acreditado 2022, 13, 4064–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquin, E.; Le Nerzé, T.; Nielassoff, E.; Beaumesnil, M.; Troussier, F.; Duverger, P. Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria En Niños y Adolescentes. EMC—Pediatría 2023, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arija-Val, V.; Santi-Cano, M.J.; Novalbos-Ruiz, J.P.; Canals, J.; Rodríguez-Martín, A.; Arija-Val, V.; Santi-Cano, M.J.; Novalbos-Ruiz, J.P.; Canals, J.; Rodríguez-Martín, A. Caracterización, Epidemiología y Tendencias de Los Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, K.M.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Body Dissatisfaction, Eating Styles, Weight-Related Behaviors, and Health among Young Women in the United States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallaram, G.K.; Sharma, P.; Kattula, D.; Singh, S.; Pavuluru, P. Body Image Perception, Eating Disorder Behavior, Self-Esteem and Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study among Female Medical Students. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berengüí, R.; Castejón, M.Á.; Torregrosa, M.S. Body Dissatisfaction, Risk Behaviors and Eating Disorders in University Students. Rev. Mex. de Trastor. Aliment. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Rizzotto, A.; Neri, S.; Currenti, W.; Guerrera, C.S.; Pirrone, C.; Coco, M.; Di Corrado, D. The Relationship between Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Young Women Aspiring Fashion Models: The Mediating Role of Stress. EJIHPE Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Qi, L.; Liu, S.; Hu, W.; Cao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Tang, M.; Lv, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Y. Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Behaviors: The Mediation Role of Smartphone Addiction and Depression. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalobos-Hernández, A.; Bojórquez-Chapela, I.; Hernández-Serrato, M.I.; Unikel-Santoncini, C. Prevalencia de conductas alimentarias de riesgo en adolescentes mexicanos: Ensanut Continua 2022. Salud Pública de México 2023, 65, s96–s101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saucedo-Molina, T.d.J.; Unikel Santoncini, C. Conductas alimentarias de riesgo, interiorización del ideal estético de delgadez e índice de masa corporal en estudiantes hidalguenses de preparatoria y licenciatura de una institución privada. Salud Ment. 2010, 33, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000–2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, Regional, and National Burden of 12 Mental Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [CrossRef]

- Glossary|National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics-z/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/glossary (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Alcohol and Young Adults Ages 18 to 25|National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics-z/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-and-young-adults-ages-18-25 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria en México: Una crisis silenciosa—UNAM Global. 2023. Available online: https://unamglobal.unam.mx/global_revista/trastornos-de-la-conducta-alimentaria-en-mexico-una-crisis-silenciosa/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Unikel-Santoncini, C.; Bojórquez-Chapela, L.; Villatoro-Velázquez, J.; Fleiz-Bautista, C.; María Elena, M.-M.I. Conductas alimentarias de riesgo en población estudiantil del Distrito Federal: Tendencias 1997–2003. Rev. De Investig. Clínica 2006, 58, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- González-Alvarado, Y.; De Jesús Saucedo-Molina, T.; Unikel-Santoncini, C. Risk of Eating Disorders in Mexican University Students. Acta Psychol. 2024, 246, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.F.M.; Libreros, G.J.O. Autopercepción de la imagen corporal y conductas alimentarias de riesgo en estudiantes universitarios de medicina en Xalapa, Veracruz, México (2014). Rev. Cienc. Salud 2019, 17, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez, R.M.C.; Escalante, M.L.Á.; Sobrino, M.d.l.C.C.; Arévalo, R.V.; Díaz, J.M.M. Restricción alimentaria y conductas de riesgo de trastornos alimentarios en estudiantes de Nutrición. Psicol. Y Salud 2008, 18, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Nicolás, I.; Molina-Pizarro, C.A.; Franco, A.R.; Arenas Castañeda, P.E.; Maya, C.; Barahona, I.; Martínez-Alés, G.; Bisquert, F.A.; Delgado-Gomez, D.; Dervic, K.; et al. What Seems to Explain Suicidality in Yucatan Mexican Young Adults? Findings from an App-Based Mental Health Screening Test Using the SMART-SCREEN Protocol. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 30767–30779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria Se Dan «en Chicas Cada Vez Más Jóvenes y En Personas Cada Vez Más Mayores»—SEPSM. Available online: https://sepsm.org/los-trastornos-de-la-conducta-alimentaria-se-dan-en-chicas-cada-vez-mas-jovenes-y-en-personas-cada-vez-mas-mayores/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Pérez-Hernández, J.A.; Téllez-Castillo, I.A.; Giraldo-Rodríguez, L.; Agudelo-Botero, M. Exploring the Burden of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa in Mexico, 1990–2021. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.; Acquarini, E.; Montecchi, L. Eating Disorders in Males. An Update. J. Psychopathol. 2022, 28, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Capuano, E.I.; Ruocco, A.; Scazzocchio, B.; Zanchi, G.; Lombardo, C.; Silenzi, A.; Ortona, E.; Varì, R. Gender Differences in Eating Disorders. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1583672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Martinez, P.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.P.; Redel-Macías, M.D.; Pagliari, C.; Vaquero-Abellan, M. Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Tena, A.R.; Badenes-Ribera, L. Body Dissatisfaction, Muscle Dysmorphia, Eating Disorder and Self-Esteem in Spanish Men of Different Sexual Orientations. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 11508–11522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, T.; Gill, E.; Drees, M.; Hamady, C.; Ludy, M.-J. Prevalence of Disordered Eating and Muscle Dysmorphia in College Students by Predominant Exercise Type. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 12, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, I.G. Grindr y la masculinidad hegemónica: Aproximación comparativa al rechazo de la feminidad. Estud. Sociológicos El Col. México 2019, 37, 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lázaro, P.M.; Pérez-Hornero, J.; Imaz-Roncero, C.; Ruiz-Lázaro, P.M.; Pérez-Hornero, J.; Imaz-Roncero, C. Disminuir La Estigmatización-Discriminación. Búsqueda de La Ayuda-Empoderamiento. Educación Emocional-Alfabetización En Salud Mental. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Brewer, K.B.; Washburn, M.; Yu, M.; de la Cruz, P.I.; Garcia Andres, A.; Torres, L.R. Mental Health Help-Seeking in Mexico. Glob. Health Promot. 2024, 31, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salud, S. de 004. Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria Afectan a 25% de Adolescentes. Available online: http://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/004-trastornos-de-la-conducta-alimentaria-afectan-a-25-de-adolescentes (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Parker, L.L.; Harriger, J.A. Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating Behaviors in the LGBT Population: A Review of the Literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Hernández, L.; Ruiz Rosas, J.A.; Ayala-Hilario, C.; Ortiz-Hernández, L.; Ruiz Rosas, J.A.; Ayala-Hilario, C. Disordered Eating Behaviors and Experiences of Violence among Mexican Youth with Different Sexual Orientations: A Population-Based Study. Salud Ment. 2021, 44, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Luna, B.S.; Escoto Ponce De León, C.; Camacho Ruíz, E.J.; Bosques Brugada, L.E. Aesthetic Ideals, Body Image, Eating Attitudes and Behaviors in Men with Different Sexual Orientation/Ideales Estéticos, Imagen Corporal, Actitudes y Conductas Alimentarias En Hombres Con Diferente Orientación Sexual. Rev. Mex. Trast. Alim. 2019, 10, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, T.; Lole, L. A Qualitative Investigation of Social Media Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and Needs Fulfilment Among Young Adults. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-García, C.A.; Cruz, G.; Espinoza, A. The Impact of Social Media on Sexual Self-Concept: A Qualitative Analysis of Instagram in Mexico. Sexes 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, F.A.; Riaz, M.M.A.; Banday, N.U.A.; Singh, A.; Arshad, Z.; Derby, H.; Sultan, M.A. Social Media Use among Adolescents with Eating Disorders: A Double-Edged Sword. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1300182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, R.C.; Melchiori, F.; Teti, A.; Albano, G.; Raffard, S.; Rodgers, R.; Lo Coco, G. The Association between Social Comparison in Social Media, Body Image Concerns and Eating Disorder Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Body Image 2025, 52, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, J.F.; Eaton, A.A. Snaps, Selfies, and Shares: How Three Popular Social Media Platforms Contribute to the Sociocultural Model of Disordered Eating Among Young Women. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, I.; Liu, S.; Portingale, J.; Croce, S.; Dar, B.; Obleada, K.; Satheesh, V.; Wong, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. A Meta-Analysis of Mortality Rates in Eating Disorders: An Update of the Literature from 2010 to 2024. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 116, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Jarman, H.K.; Liu, C.; Anderson, C.; McClure, Z.; Messer, M. Mental Health Impacts of Self-Help Interventions for the Treatment and Prevention of Eating Disorders. A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 58, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.J.; Raut, T.; Le, L.K.-D.; Hay, P.; Ananthapavan, J.; Lee, Y.Y.; Mihalopoulos, C. The Association between Eating Disorders and Mental Health: An Umbrella Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshe, E.; Paxton, S.; Miskovic-Wheatley, J.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; et al. Prevention and Early Intervention in Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriter, C.; Ray, L.A. Binge Eating and Binge Drinking: An Integrative Review. Eat. Behav. 2011, 12, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Pompili, S.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Baiocco, R. Psychological Characteristics and Eating Attitudes in Adolescents with Drunkorexia Behavior: An Exploratory Study. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2020, 25, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. Datos Sobre El Comportamiento Suicida En México. 2024. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2025/EAP_Suicidio_25.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ramírez-Toscano, Y.; Canto-Osorio, F.; Carnalla, M.; Colchero, M.A.; Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; López-Olmedo, N. Patrones de consumo de alcohol en adolescentes y adultos mexicanos: Ensanut Continua 2022. Salud Pública De México 2023, 65, s75–s83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Díaz, Y.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Ramos-Méndez, M.Á.; Juárez-Rojop, I.E.; Tovilla-Zárate, C.A.; González-Castro, T.B.; López-Narváez, M.L.; Nicolini, H. Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mexican Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.R. Classification of Epidemiologic Research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988, 41, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The Assessment of Binge Eating Severity among Obese Persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, O.; Robles, R. Validez de constructo y consistencia interna del Cuestionario de Trastorno por Atracón en población mexicana con obesidad. Psiquis 2006, 15, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez-Aguilar, M.; Vázquez-Arévalo, R.; López-Aguilar, X.; Regalado-Ruíz, L.A. Validación y punto de corte de la Escala de Atracón Alimentario (BES) en población mexicana. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2022, 14, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, E.Y.E.; López, M.V.; Guadarrama, R.G.; Rodríguez, M.P. Efecto de las conductas alimentarias de riesgo sobre el bienestar subjetivo de adolescentes de bachillerato. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Y Valores 2024, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constaín, G.A.; Ricardo Ramírez, C.; Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.D.L.Á.; Álvarez Gómez, M.; Marín Múnera, C.; Agudelo Acosta, C. Validez y utilidad diagnóstica de la escala EAT-26 para la evaluación del riesgo de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en población femenina de Medellín, Colombia. Atención Primaria 2014, 46, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D.M. Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26): Scoring and Interpretation. Available online: https://www.eat-26.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EAT-26IntpretScoring-Test-11-1-17.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Lugo Salazar, K.J.; Pineda García, G. Propiedades psicométricas del Test de Actitudes Alimentarias (EAT-26) en una muestra no clínica de adolescentes. Cuad. Hispanoam. Psicol. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.J.; Taylor, M.J.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 64, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, M.J.A.; Nahas, F.X.; Cordás, T.A.; Gama, M.G.; Sucupira, E.R.; Ramos, T.D.; Felix, G.d.A.A.; Ferreira, L.M. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptoms and Body Weight Concerns in Patients Seeking Abdominoplasty. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2016, 36, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Arévalo, R.; Galán Julio, J.; López Aguilar, X.; Alvarez Rayón, G.L.; Mancilla Díaz, J.M.; Caballero Romo, A.; Unikel Santoncini, C. Validez del Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) en Mujeres Mexicanas. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2011, 2, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, D.R.; Sasse, D.K. An Exploration of the Drive for Muscularity in Adolescent Boys and Girls. J. Am. Coll. Health 2000, 48, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandón-Nagel, N.; Baeza Rivera, M.; Said, J.; Mardones, E. Propiedades Psicométricas Del Drive for Muscularity Scale (DMS) En Una Muestra de Hombres y Mujeres Jóvenes Chilenos. Rev. Psicopatología Y Psicol. Clínica 2021, 26, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoto, C.; Alvarez-Rayón, G.; Mancilla-Díaz, J.M.; Camacho Ruiz, E.J.; Franco Paredes, K.; Juárez Lugo, C.S. Psychometric Properties of the Drive for Muscularity Scale in Mexican Males. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2013, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsever, I.; Matusiak, Ł.; Szepietowska, M.; Evans, C.; Szepietowski, J.C. Body Shape Questionnaire-34 (BSQ) and Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS)—Pertinent Body Image Screening Tools: Creation and Validation of Polish Language Versions. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.G.; Almeida, M.; de Oliveira Júnior, M.L.; Brown, T.A.; de Carvalho, P.H.B. Psychometric Evaluation of the Drive for Muscularity Scale and the Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory among Brazilian Cisgender Gay and Bisexual Adult Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.; Lundh, L.-G.; Andersson, G. Attentional Bias for Negative Self-Words in Young Women The Role of Thin Ideal Priming and Body Shape Dissatisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Morcillo, J.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Rodríguez-Besteiro, S.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. The Association of Body Image Perceptions with Behavioral and Health Outcomes among Young Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terol-Cantero, M.C.; Cabrera-Perona, V.; Martín-Aragón, M. Revisión de estudios de la Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (HAD) en muestras españolas. Analesps 2015, 31, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriguete Meléndez, J.A.; Pérez Bustinzar, A.R.; Vega Morales, R.I.d.l.; Barriguete Chávez-Peón, P.; Rojo Moreno, L. Validación de la Escala Hospitalaria de Ansiedad y Depresión en población mexicana con trastorno de la conducta alimentaria. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2017, 8, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Silva, F.D.; García-Grimshaw, M.; Valdés-Ferrer, S.I.; Vigueras-Hernández, A.P.; Domínguez-Moreno, R.; Tristán-Samaniego, D.P.; Michel-Chávez, A.; González-Duarte, A.; Vega-Boada, F.A.; Reyes-Melo, I.; et al. Neurologic Manifestations in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Mexico City. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (Hads) En Mexicanos Con Asma: Confiabilidad y Validez Psicología Iberoamericana. Available online: https://psicologiaiberoamericana.ibero.mx/index.php/psicologia/article/view/25 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Scoring the AUDIT. Available online: https://auditscreen.org/about/scoring-audit (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. Departamento de Salud Mental y Dependencia de Sustancias. Available online: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/Auditmanual_ENG.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An Updated Literature Review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Quintero, L.A.; Moral Jiménez, M.d.l.V.; Rojas Solís, J.L.; Bringas Molleda, C.; Soto Chilaca, A.; Rodríguez Díaz, F.J. Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) in Adolescents and Young Adults from Southern Mexico. Alcohol. 2019, 81, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/es-es/products/spss-statistics?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=16404563709&p5=e&p9=176153910670&gclsrc=aw.ds&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22040159470&gbraid=0AAAAA-oJ0vIebQdu8f32712MXBlt3AdwC&gclid=CjwKCAiA55rJBhByEiwAFkY1QEj3yM1s5P_BqdPx39hhFXAMolS4Hv1WuRBNpDjpZe8vhbRjUeD4UBoCkHwQAvD_BwE (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Python Software Foundation. Python (Version 3.11); Python Software Foundation: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UNAM—UNAM Tucson. Available online: https://tucson.unam.mx/unam/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Hernandez-Chan, G.; Villanueva-Escalante, M.; Sosa-Correa, M.; Jimenez-Coello, M.; Vanega-Romero, S. Hábitos Alimenticios Como Factor de Salud Mental En Estudiantes Universitarios de Yucatán. Cienc. Y Humanismo En La Salud 2024, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Mora, M.E.; Genis-Mendoza, A.D.; Villatoro Velázquez, J.A.; Bustos-Gamiño, M.; Bautista, C.F.; Camarena, B.; Martínez-Magaña, J.J.; Nicolini, H. The Prevalence of Symptomatology and Risk Factors in Mental Health in Mexico: The 2016–17 ENCODAT Cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro-Piquero, P.; Zancada-Menéndez, C.; Bernabéu-Brotons, E.; Moreno-Fernández, R.D. The Relationship between Binge Drinking and Binge Eating in Adolescence and Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, C.E.; Silverstein, S.; Askew, A.J.; Simone, M.; Galupo, M.P.; Levinson, C.A. Eating Disorders Among Queer and Trans Individuals: Implications for Conceptualization, Assessment, and Treatment. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2024, 88, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INEGI. Estadísticas a Propósito Del Día Mundial Para La Prevención Del Suicidio. 2018. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2018/suicidios2018_Nal.docx (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Reyes-Foster, B.; Duncan, W. Facing Mexico’s Mental Health Fallout: The Most Vulnerable Populations Lack Access to Mental Health Services as the COVID-19 Pandemic Taxes the Country’s Already-Stressed Healthcare Infrastructure. NACLA Rep. Am. 2020, 52, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Highlights. Available online: https://nedc.com.au/research/research-highlights (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Giel, K.E.; Bulik, C.M.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Hay, P.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Schag, K.; Schmidt, U.; Zipfel, S. Binge Eating Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escolar-Llamazares, M.C.; Martínez Martín, M.Á.; González Alonso, M.Y.; Medina Gómez, M.B.; Mercado Val, E.; Lara Ortega, F. Risk factors of eating disorders in university students: Estimation of vulnerability by sex and age. Trastor. Aliment. 2017, 8, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Lewis-Smith, H.; Slater, A.; Bray, I. Body Dissatisfaction Predicts the Onset of Depression among Adolescent Females and Males: A Prospective Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 75, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, A.; Bhatia, K. The Social Media Diet: A Scoping Review to Investigate the Association between Social Media, Body Image and Eating Disorders amongst Young People. PLOS Glob. Public. Health 2023, 3, e0001091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geografía(INEGI). Encuesta Nacional sobre Disponibilidad y Uso de Tecnologías de la Información en los Hogares (ENDUTIH) 2019. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/dutih/2019/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Bogusz, K.; Kopera, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Trucco, E.M.; Kucharska, K.; Walenda, A.; Wojnar, M. Prevalence of Alcohol Use Disorder among Individuals Who Binge Eat: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Addiction 2021, 116, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBCO 2018. Available online: http://www.cij.gob.mx/ebco2018-2024/9930/9930CD.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Horváth, Z.; Román, N.; Elekes, Z.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; Urbán, R. Alcohol Consumption and Risk for Feeding and Eating Disorders in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Drinking Motives. Addict. Behav. 2020, 107, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health Issues: Alcohol Use Disorder and Common Co-Occurring Conditions|National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/health-professionals-communities/core-resource-on-alcohol/mental-health-issues-alcohol-use-disorder-and-common-co-occurring-conditions#pub-toc1 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Keusch, F.; Bach, R.; Cernat, A. Reactivity in Measuring Sensitive Online Behavior. Internet Res. 2022, 33, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.G.; Pieters, R. Assessing Sensitive Consumer Behavior Using the Item Count Response Technique. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnambs, T.; Kaspar, K. Disclosure of Sensitive Behaviors across Self-Administered Survey Modes: A Meta-Analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 1237–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, V.; Gliori, G.; Näsman, P.; Sundling, C. Comparing Responses from a Paper-Based Survey with a Web-Based Survey in Environmental Criminology. Crime. Prev. Community Saf. 2024, 26, 216–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Keel, P.K. Eating Disorders in Boys and Men. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 19, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Murray, S.; Compte, E.J.; Song, J.; Nagata, J.M. The Muscularity-Oriented Eating Test, Drive for Muscularity Scale, and Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory among Chinese Men: Confirmatory Factor Analyses. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 11690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralph-Nearman, C.; Yeh, H.; Khalsa, S.S.; Feusner, J.D.; Filik, R. What Is the Relationship between Body Mass Index and Eating Disorder Symptomatology in Professional Female Fashion Models? Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reivan Ortiz, G.G.; Elizalde, B.; Tapia, C.; Granero, R. Psychoneurological Links Contributing to Body Mass Index and Eating Disorder Severity. Nutrients 2025, 17, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIIES. Available online: https://www.siies.unam.mx/reporte.php?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 November 2025).

| Variable | UADY (n = 457) | UNAM (n = 153) | Statistic | Total (n = 610) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | p | n (%) | |

| Sex assigned at birth | |||||

| Man | 172 (37.6) | 58 (37.9) | 0.001 | <0.001 | 230 (37.7) |

| Woman | 285 (62.4) | 95 (62.1) | 380 (62.3) | ||

| Gender identity | |||||

| Cisgender men | 169 (37.0) | 55 (35.9) | 12.97 | 0.002 | 224 (36.7) |

| Cisgender women | 281 (61.5) | 87 (56.9) | 368 (60.3) | ||

| Non-cisgender * | 7 (1.5) | 11 (7.2) | 18 (3.0) | ||

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 377 (82.5) | 95 (62.1) | 30.95 | <0.001 | 472 (77.4) |

| Bisexual | 58 (12.7) | 39 (25.5) | 97 (15.9) | ||

| Homosexual | 19 (4.2) | 11 (7.2) | 30 (4.9) | ||

| Other | 3 (0.7) | 8 (5.2) | 11 (1.8) | ||

| Major | 264.3 | <0.001 | |||

| Medicine | 193 (42.2) | 98 (64.1) | 291 (47.7) | ||

| Nutrition | 177 (38.7) | 0 (0) | 177 (29.0) | ||

| Physical Rehabilitation | 87 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 87 (14.3) | ||

| Other majors * | 0 (0) | 55 (35.9) | 55 (9.0) | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction (BD) | 3.08 | 0.079 | |||

| Low BD | 236 (51.6) | 67 (43.8) | 303 (49.7) | ||

| High BD | 221 (48.4) | 86 (56.2) | 307 (50.3) | ||

| M ± SD | M ± SD | Z | p | Total M ± SD | |

| Age (years) | 20.91 ± 2.57 | 22.07 ± 3.85 | −3.21 | <0.001 | 21.20 ±2.9 |

| Symptoms of depression and anxiety (HADS) | 14.60 ± 4.75 | 18.97 ±1.86 | −8.81 | <0.001 | 15.69 ±5.19 |

| Alcohol consumption (AUDIT) | 1.86 ±3.03 | 3.24 ±4.40 | −3.50 | <0.001 | 2.20 ±3.48 |

| Body dissatisfaction—Women (BSQ) | 87.54 ± 30.03 | 101 ± 39.09 | −2.73 | 0.006 | 90.90 ±32.98 |

| Body dissatisfaction-Men (DMS) | 42.12 ± 14.97 | 40.98 ± 13.85 | 0.34 | 0.737 | 41.83 ±13.68 |

| BED symptomatology (BES) | 8.02 ± 6.67 | 11.03 ± 8.41 | −3.86 | <0.001 | 8.77 ± 7.25 |

| High-risk eating behaviors (EAT-26) | 6.99 ± 7.44 | 9.37 ± 9.96 | −2.59 | 0.009 | 7.57 ± 8.19 |

| Group | Significant ED Symptomatology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) | OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| College | |||||

| UADY | 457 | 71 (15.5) | - | - | <0.001 |

| UNAM | 153 | 50 (32.7) | 2.64 | [1.73–4.03] | |

| Sex assigned at birth | |||||

| Men | 230 | 27 (11.7) | - | - | <0.001 |

| Women | 380 | 121 (31.8) | 2.47 | [1.55–3.92] | |

| Gender identity | |||||

| Cisgender men | 224 | 25 (11.2) | - | - | <0.001 |

| Cisgender women | 368 | 91 (24.7) | 2.62 | [1.62–4.22] | |

| Non-cisgender * | 18 | 5 (27.8) | 3.06 | [1.01–9.30] | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 472 | 82 (17.4) | - | - | <0.001 |

| Bisexual | 97 | 32 (32.9) | 2.34 | [1.44–3.81] | |

| Homosexual | 30 | 5 (16.7) | 0.95 | [0.35–2.56] | |

| Others | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 1.78 | [0.46–6.84] | |

| Major | |||||

| Medicine | 291 | 63 (21.6) | - | - | 0.029 |

| Nutrition | 177 | 24 (13.6) | 0.58 | [0.34–0.99] | |

| Physical Rehabilitation | 87 | 17 (19.5) | 0.87 | [0.46–1.64] | |

| Other majors * | 55 | 17 (30.9) | 1.68 | [0.87–3.25] | |

| Body Dissatisfaction-Women (BSQ) | |||||

| Low BD | 101 | 11 (3.6) | - | - | <0.001 |

| High BD | 104 | 90 (46.4) | 3.68 | [2.64–4.70] | |

| Body Dissatisfaction-Men (DMS) | |||||

| Low BD | 182 | 4 (2.2) | - | - | 0.005 |

| High BD | 86 | 19 (18.1) | 1.31 | [0.35–2.28] | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College | 0.174 | |||||

| UADY (ref) | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| UNAM | 0.49 | 0.36 | 1.85 | 1.64 | [0.80–3.35] | 0.174 |

| Major | 0.542 | |||||

| Medicine (ref) | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nutrition | −0.46 | 0.34 | 1.86 | 0.63 | [0.33–1.21] | 0.172 |

| Physical Rehabilitation | −0.11 | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.89 | [0.41–1.92] | 0.759 |

| Others | −0.21 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.82 | [0.33–1.97] | 0.651 |

| Gender identity | <0.001 | |||||

| Cisgender women (ref) | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cisgender men | −1.196 | 0.29 | 17.0 | 0.30 | [0.17–0.53] | <0.001 |

| Non-cisgender * | −0.77 | 0.63 | 1.47 | 0.47 | [0.13–1.64] | 0.226 |

| Sexual orientation | 0.490 | |||||

| Heterosexual (ref) | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bisexual | 0.41 | 0.30 | 1.81 | 1.50 | [0.83–2.71] | 0.179 |

| Homosexual | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 1.31 | [0.41–4.18] | 0.614 |

| Others ** | −0.51 | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.60 | [0.08–4.56] | 0.604 |

| Body dissatisfaction | <0.001 | |||||

| Low BD (ref) | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| High BD | 2.60 | 0.34 | 56.94 | 13.46 | [6.79–26.26] | <0.001 |

| Symptoms of anxiety and depression (HADS) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 12.65 | 1.10 | [1.04–1.16] | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption (AUDIT) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2.89 | 1.06 | [0.99–1.12] | 0.089 |

| Constant | −4.59 | 0.54 | 72.21 | 0.01 | - | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso-Catalán, M.; Tafoya, S.A.; Vazquez-Arevalo, R.; Ávila-Escalante, M.L.; Tusié-Luna, M.T.; Moreno-Macías, L.; Moreno-Macías, H.; Corral-Aguilar, J.; Aburto-Arciniega, M.; Silva-Avalos, S.; et al. Frequency, Correlates, and Symptom Severity of Eating Disorders Among College Students in Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121797

Alonso-Catalán M, Tafoya SA, Vazquez-Arevalo R, Ávila-Escalante ML, Tusié-Luna MT, Moreno-Macías L, Moreno-Macías H, Corral-Aguilar J, Aburto-Arciniega M, Silva-Avalos S, et al. Frequency, Correlates, and Symptom Severity of Eating Disorders Among College Students in Mexico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121797

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso-Catalán, María, Silvia A. Tafoya, Rosalia Vazquez-Arevalo, María Luisa Ávila-Escalante, María Teresa Tusié-Luna, Lidia Moreno-Macías, Hortensia Moreno-Macías, Julián Corral-Aguilar, Mónica Aburto-Arciniega, Santiago Silva-Avalos, and et al. 2025. "Frequency, Correlates, and Symptom Severity of Eating Disorders Among College Students in Mexico" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121797

APA StyleAlonso-Catalán, M., Tafoya, S. A., Vazquez-Arevalo, R., Ávila-Escalante, M. L., Tusié-Luna, M. T., Moreno-Macías, L., Moreno-Macías, H., Corral-Aguilar, J., Aburto-Arciniega, M., Silva-Avalos, S., Coronel-Manzo, D. A., Guerrero-López, B., & Díaz-Olavarrieta, C. (2025). Frequency, Correlates, and Symptom Severity of Eating Disorders Among College Students in Mexico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121797