Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison and an Update

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- FBDG title, year of publication, years since the last revision, and available languages.

- Intended purpose and intended use of FBDG (target population; whether it was indicated that it could be used by policymakers or healthcare practitioners, etc.; whether it included special population groups).

- Pictorial illustration.

- Food groups included in the guidelines and whether quantitative recommendations were provided (number of servings from various food groups and definitions of servings). For further comparative purposes, food group and quantitative recommendations from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dietary Guidelines and selected European national guidelines were also examined.

- Dietary intake/behavior recommendations.

- Recommendations related to health-related behaviors (including the maintenance of healthy body weight, engaging in physical activity, promoting adequate sleep, and emotional well-being).

- Non-dietary recommendations (including food and water safety and food labeling).

- Cost and affordability considerations.

- Environmental sustainability considerations.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the National FBDGs in Countries of the EMR

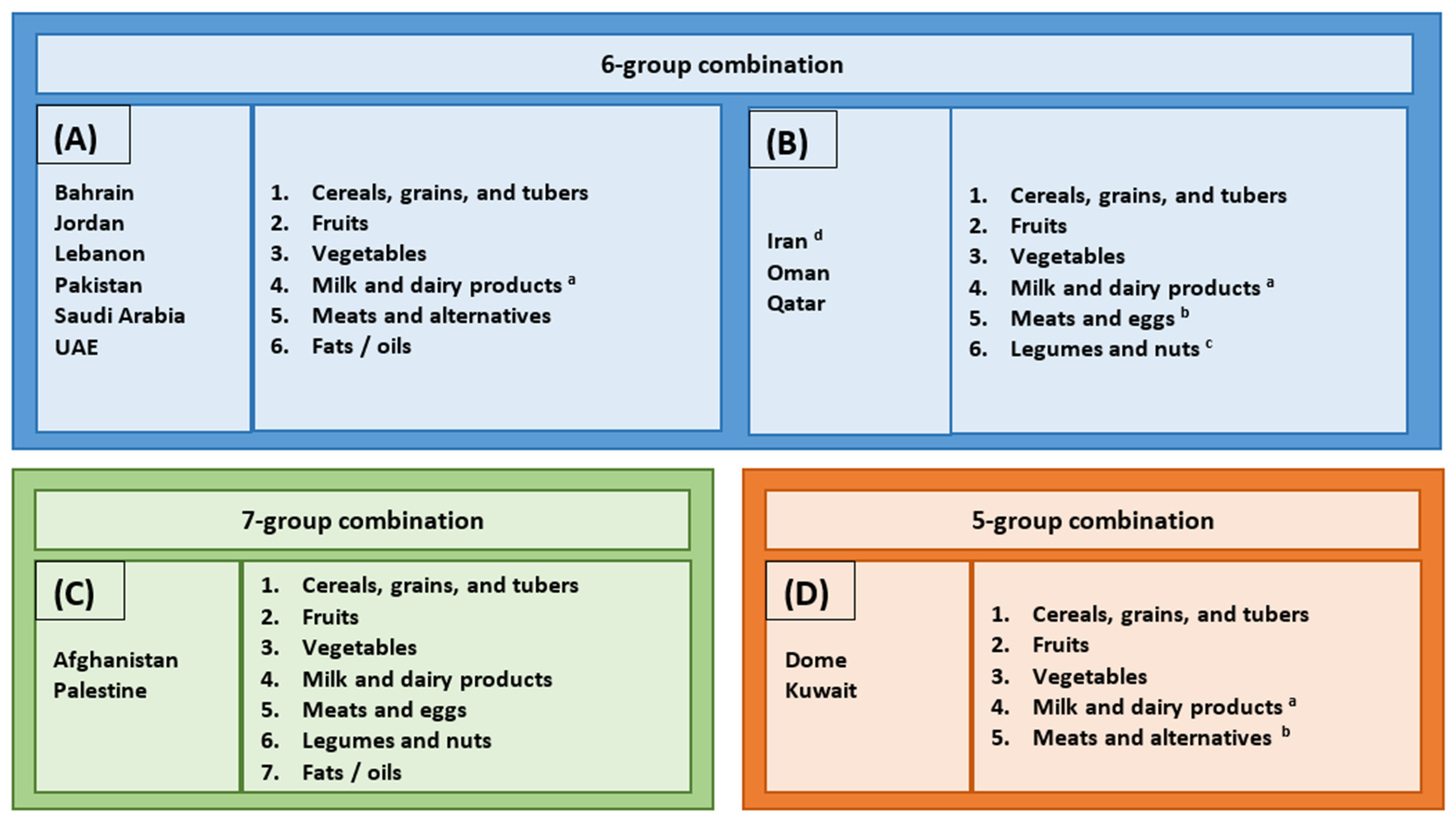

3.2. Food Groupings

3.3. Quantitative Food Groups’ Recommendations

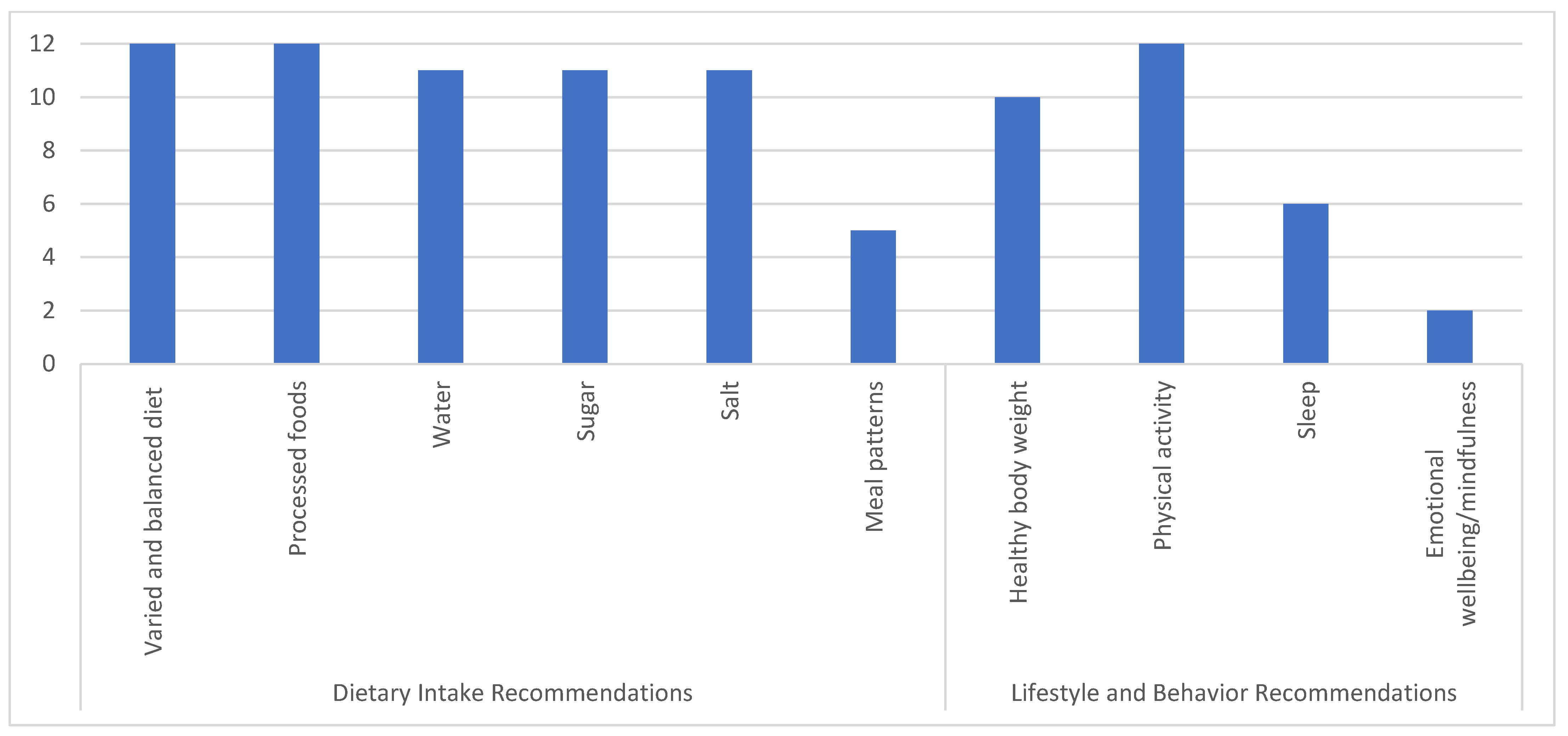

3.4. Dietary Intake/Behavior Recommendations Tackled by the National FBDGs in the EMR

3.4.1. Varied and Balanced Diet

3.4.2. Processed Foods

3.4.3. Beverages

3.4.4. Sugar

3.4.5. Salt

3.4.6. Meal Patterns

3.5. Lifestyle and Behavior Recommendations Tackled by the National FBDGs in the EMR

3.5.1. Healthy Body Weight

3.5.2. Physical Activity

3.5.3. Sleep

3.5.4. Emotional Well-Being/Mindfulness

3.6. Non-Dietary Recommendations Presented in the FBDGs of the EMR Countries

3.6.1. Safe Food and Water

3.6.2. Cost and Affordability

3.6.3. Food Labeling

3.6.4. Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMR | Eastern Mediterranean Region |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agricultural Organization |

| FBDGs | food-based dietary guidelines |

| G6PD | glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| HCP | healthcare practitioners |

| LW | lactating women |

| NCDs | non-communicable diseases |

| PW | pregnant women |

| SSBs | sugar-sweetened beverages |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WRA | women of reproductive age |

Appendix A

| Seven-Group Categorization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan [29] Three Energy Levels (1300, 2200, 2800 kcals) | Palestine [37] (Serving Recommendations Vary per Age and Gender) | |

| Cereals, grains, and tubers | 2.5, 6, 8 servings | 3–8 servings |

| Fruits | 2.5, 2.5, 3 servings | 1–2 servings |

| Vegetables | 2.5, 3, 3 servings | 1–3 servings |

| Milk and dairy products | 2, 3.5, 4 servings | 2–3 servings |

| Meats and eggs | 1.5, 2, 2.5 servings | 2–6 servings |

| Legumes and nuts | 0.5, 1.5, 2 servings | 2–6.5 servings |

| Fats/Oils | 4.5, 5.5, 7 servings | Limited intake |

| Six-group categorization (A) | ||||||||

| USDA 2020–2025 [52] (Based on a 2000 kcal Regular Diet) * | WHO-EMR [25] | Bahrain [30] | Jordan [32] | Lebanon [34] | Pakistan [36] | Saudi Arabia [39] | UAE [40] (Serving Recommendations Vary per Age and Gender) | |

| Cereals, grains, and tubers | 6 oz equivalents | 180 g equivalent | 6 servings | At least 6 servings | At least 6 servings, with at least ½ being whole grain | 4–5 servings | 6–11 servings | 3–8 oz |

| Fruits | 2 cup equivalents | 4 servings | 2 servings | 2 servings | 2 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–4 servings | 1–2 cups |

| Vegetables | 2.5 cup equivalents | 5 servings | 2.5 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–3 servings | 3–5 servings | 1–3 cups |

| Milk and dairy products | 3 cup equivalents | 3 cup equivalents | 3 servings | 3 servings | 3 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–4 servings | 2–3 cups |

| Meat and alternatives | 5.5 oz equivalents | 160 g equivalent | 5.5 servings | 5–6.5 servings | 5–6.5 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–3 servings | 2–6.5 oz |

| Fats/Oils | 27 g | 24 g oils, 267 kcal solid fat and added sugars | 27 g oils | Limited consumption | Limited consumption | Limited consumption | Lower amount possible | 3–7 tsp |

| Six-group categorization (B) | ||||||||

| Iran [31] | Oman [35] | Qatar [38] | ||||||

| Cereals, grains, and tubers | Choose whole grains | 6 servings | Choose whole grains | |||||

| Fruits | Eat 3 times a day | 2 servings | 2–4 servings | |||||

| Vegetables | Eat raw and cooked vegetables every day at main meals and snacks | 2–5 servings | 3–5 servings | |||||

| Milk and dairy products | Consume dairy products daily | 3 servings | Maintain a daily consumption of skimmed or low-fat milk and dairy products | |||||

| Meats and eggs | Include meats, preferably chicken and fish (with skin removed), as well as eggs, in your diet | 5.5 servings | Choose skinless poultry and lean cuts of meat, eat a variety of fish at least twice per week | |||||

| Legumes and nuts | Eat legumes and dishes made with legumes once a day | 5.5 servings of protein per day | Eat legumes daily; choose legumes, nuts, and seeds as alternative protein sources | |||||

| Musaiger Gulf Countries (Dome) [26] | Kuwait [33] | |

|---|---|---|

| Cereals, grains, and tubers | 6–11 servings | 7 servings for women, 8 servings for men |

| Fruits | 2–4 servings | 4 servings |

| Vegetables | 3–5 servings | 5 servings |

| Milk and dairy products | 2–3 servings | 2–3 servings |

| Meats and alternatives | 2–4 servings | 2 servings for women, 3 servings for men |

| Denmark–Northern Europe [52,53] | Germany–Western Europe [53,54] | Latvia–Eastern Europe [53,55] | Spain–Southern/Mediterranean Europe [53,56] | Ireland–British Isles [53,57] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starchy foods | At least 90 g of whole grains a day | 5 servings a day, with at least 1/3 being whole grains | 4–6 servings a day, particularly whole grains | 3–6 servings a day | 3–5 servings a day |

| Fruits and vegetables | 6 servings (or 600 g, half of which at least are vegetables) a day | At least 5 servings a day | At least 5 servings (or 500g) a day | At least 5 servings a day | 5–7 servings a day |

| Milk and dairy products | 250–350 mL milk or dairy products and 20 g of cheese a day | 2 servings a day | 2–3 servings a day | Maximum 3 servings a day | 3 servings a day |

| Meats and alternatives |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fats/Oils | - | 1 tablespoon of vegetable oils and 1 tablespoon of butter or margarine a day | An average of 67–80 g (i.e., no more than 25–30% of the daily energy needs) | - | - |

References

- Neuhouser, M.L. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutr. Res. 2019, 70, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, S.H.; Hamdy, O.; Mohan, V.; Hu, F.B. Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: Dietary components and nutritional strategies. Lancet 2014, 383, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.G.; Ford, N.A.; Hu, F.B.; Zelman, K.M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. A healthy approach to dietary fats: Understanding the science and taking action to reduce consumer confusion. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeland-Graves, J.H.; Nitzke, S. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Total diet approach to healthy eating. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnese, C.; Santarpia, L.; Buonifacio, M.; Nardelli, A.; Caldara, A.R.; Silvestri, E.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. European food-based dietary guidelines: A comparison and update. Nutrition 2015, 31, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization; World Health Organization. Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines/Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Consultation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. FAO/WHO Technical Consultation on National Food-based Dietary Guidelines; FAOUN and WHO EMRO: Cairo, Egypt, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bechthold, A.; Boeing, H.; Tetens, I.; Schwingshackl, L.; Nöthlings, U. Perspective: Food-based dietary guidelines in Europe—Scientific concepts, current status, and perspectives. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Álvarez, E.; Boeckx, H.; Penne, T.; Palma Linares, I.; Storms, B.; Goedemé, T. A comparison of European countries FBDG in the light of their contribution to tackle diet-related health inequalities. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization; World Health Organization. Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles. Rome. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6640en/ca6640en.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Faber, M.; de Villiers, A. Field-testing of food-based dietary guidelines. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 34, i–ii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, K.B.; Miller, G.D.; Boileau, A.C.; Masiello Schuette, S.N.; Giddens, J.C.; Brown, K.A. Global review of dairy recommendations in food-based dietary guidelines. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 671999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines: Regions. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/en/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Fischer, C.G.; Garnett, T. Plates, Pyramids and Planets. Developments in National Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Guidelines: A State of Play Assessment; 9251092222; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and The Food Climate Research Network: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Poor Nutrition Is Increasing Rates of Diabetes, Cancers, Heart Attacks and Stroke. WHO Launches Regional Nutrition Strategy to Help Countries Beat NCDs. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/media/news/poor-nutrition-is-increasing-rates-of-diabetes-cancers-heart-attacks-and-stroke.html (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Leppäniemi, H.; Ibrahim, E.T.; Abbass, M.M.; Borghi, E.; Flores-Urrutia, M.C.; Dominguez Muriel, E.; Gatica-Dominguez, G.; Kumapley, R.; Hammerich, A.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Nutrition Profile for Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region with different income levels: An Analytical Review. Children 2023, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sharjabi, S.J.; Al Jawaldeh, A.; Hassan, O.E.H.; Dureab, F. Understanding the Food and Nutrition Insecurity Drivers in Some Emergency-Affected Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from 2020 to 2024. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Double Burden of Malnutrition: Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hwalla, N.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Radwan, H.; Alfawaz, H.A.; Fouda, M.A.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Zaghloul, S.; Blumberg, J.B. The prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies and inadequacies in the Middle East and approaches to interventions. Nutrients 2017, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, L.; Ayoub, J.J.; Al Jawaldeh, A. Review of the nutrition situation in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Itani, L.; Hamade, R.; Chamieh, M.C.; Hwalla, N. Mediterranean diet and its environmental footprints amid nutrition transition: The case of Lebanon. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul Enein, B.H.; Bernstein, J.; Neary, A. Dietary transition and obesity in selected Arabic-speaking countries: A review of the current evidence. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; Houalla, N.; Al-Jawaldeh, A.E.; Bagchi, K.; Hachem, F.; El Ati, J.; Omidvar, N.; Cheikh, L. Promoting a Healthy Diet for the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: User-Friendly Guide; WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, L.; Bernstein, J.; Dodge, E.; Bechard, L.; Aboul-Enein, B.H. Food-based dietary guidelines of Arabic-speaking countries: A culturally congruent profile. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Countries. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/countries.html (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/home (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Food and Agriculture Organization; Ministry of Public Health Afghanistan; Ministry of Agriculture Afghanistan; Ministry of Education Afghanistan. National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Afghans. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i5283e/i5283e.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Ministry of Health-Bahrain. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for the Kingdom of Bahrain. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.bh/Content/Upload/File/638422157715028884-225MOH---The-Food-National-Based-Dietary-Guidelines_.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—Iran. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/iran/en/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Ministry of Health (MOH) Jordan. Food Based Dietary Guideline for Jordanians (Arabic). Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jo/ebv4.0/root_storage/ar/eb_list_page/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%84_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%BA%D8%B0%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A_%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%86.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Public Authority for Food and Nutrition. Kuwait Food Based Dietary Guideline. Available online: https://www.pafn.gov.kw/assets/images/Uploads/KuwaitFoodbasedDietaryGuidlineEnglish.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- The American University of Beirut; Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research; Ministry of Public Health. The Food-Based Dietary Guideline Manual for Promoting Healthy Eating in the Lebanese Adult Population. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/lebanon/en/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Ministry of Health-Sultanate of Oman. The Omani Guide for Healthy Eating. Available online: https://moh.gov.om/media/c3vhtd2y/oman-diatry-guideline-english-feb-19.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Ministry of Planning/Development and Reform/Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Dietary Guidelines for Better Nutrition. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/report/Pakistan_Dietary_Nutrition_2019.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Ministry of Public Health Palestine; World Health Organization. Palestinian Food Based Dietary Guidelines (Arabic); Ministry of Health: Ramallah, Palestine, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Supreme Council of Health. Qatar Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/az908e/az908e.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Ministry of Health Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Dietary Guidelines for Saudis: The Healthy Food Palm. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/saudi-arabia/en/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- United Arab Emirates Ministry of Health and Prevention. United Arab Emirates Dietary Guidelines (Arabic). Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/united-arab-emirates/en/ (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- The World Bank. The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Alhumaidan, O.A.; Alkhunein, S.M.; Alakeel, S.A.; Fallata, G.A.; Aldhwayan, M.M.; Alfaifi, A.Y.; Albalwi, W.M.; AlZeer, H. Saudi healthy plate-2024: Framework for developing, modeling, and evaluating Saudi Arabia’s dietary guidelines. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Afghanistan. Afghanistan Launches National Food Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDGs) for Improved Nutrition. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-launches-national-food-based-dietary-guidelines-fbdgs-improved (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Naja, F.; Khaleel, S.; Alhajeri, M.E.; Ajlan, B.Y.; Abulfateh, N.M.; Alawadhi, A.G.; Bowah, M.H.J.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. The Bahraini food based dietary guidelines: A holistic perspective to health and wellbeing. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1182075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, S.; Omidvar, N.; Djazayery, A.; Minaie, M.; Hooshiarrad, A.; Sheikoleslam, R. Development of food-based dietary guidelines for Iran: A preliminary report. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 51, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A. Development of Food Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339322960_DEVELOPMENT_OF_FOOD_BASED_DIETARY_GUIDLINES?channel=doi&linkId=5e4b367ba6fdccd965aee258&showFulltext=true (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Musaiger, A.O.; Takruri, H.R.; Hassan, A.S.; Abu-Tarboush, H. Food-based dietary guidelines for the Arab Gulf countries. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 905303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines: Development Process. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/dietary-guidelines/background/development-process/en/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Al Shhawi, A.; World Health Organization; Ministry of Health (MOH) Libya; National Centre for Diease Control Libya. Dietary Guidelines for Chronic Diseases in Libya (Arabic); National Center for Disease Control: Tripoli, Libya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Yemen/Ministry of Public Health and Population. National Nutrition Strategy for Yemen (Draft). Available online: https://cmamforum.org/Pool/Resources/YEMEN-National-Nutrition-Strategy-2009.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Danish Veterinary and Food Administration; Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark. The Official Dietary Guidelines—Good for Health and Climate. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/denmark/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- European Commission. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Europe: Source Documents. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-source-documents-food_en (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- German Nutrition Society. Eat and Drink Well—Recommendations of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/germany/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Ministry of Health-Latvia and Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Dietary Guidelines for Adults. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/latvia/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) of the Spanish Ministry of Consumer Affairs. Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Recommendations Complemented with Physical Activity Recommendations for the Spanish Population. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/spain/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Department of Health-Ireland. Healthy Food for Life—The Healthy Eating Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/ireland/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Naureen, Z.; Bonetti, G.; Medori, M.C.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Bertelli, M. Foods of the Mediterranean diet: Garlic and Mediterranean legumes. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. Expert Report: Diet, Nutrition and Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 916; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Programme Initiative. A Healthy Diet for a Healthy life. The Vision for 2030. Available online: https://era.gv.at/public/documents/1320/Vision_paper.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 894; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Halleröd, B.; Rothstein, B.; Daoud, A.; Nandy, S. Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low-and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2013, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; McKee, M. A comparative analysis of health policy performance in 43 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.M.; Kassis, A.N.; Ayoub, J.J.; Naja, F.A.; Hwalla, N.C. Nutritional status and dietary intakes of children amid the nutrition transition: The case of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Nutr. Res. 2018, 57, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C. Uneven dietary development: Linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Glob. Health 2006, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehio Sibai, A.; Nasreddine, L.; Mokdad, A.H.; Adra, N.; Tabet, M.; Hwalla, N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: Reviewing the evidence. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 57, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, L.; Naja, F.; Sibai, A.; Helou, K.; Adra, N.; Hwalla, N. Trends in nutritional intakes and nutrition-related cardiovascular disease risk factors in Lebanon: The need for immediate action. J. Med. Liban. 2013, 62, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/noncommunicable-diseases/publications/burden-of-noncommunicable-diseases-in-the-eastern-mediterranean-region.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update; 9240683461; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Monda, A.; de Stefano, M.I.; Villano, I.; Allocca, S.; Casillo, M.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Moscatelli, F.; Dipace, A.; Limone, P. Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Increased Risk of Obesity: A Narrative Review. Foods 2024, 13, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Blanco, L.; de la O, V.; Santiago, S.; Pouso, A.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. High consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with increased risk of micronutrient inadequacy in children: The SENDO project. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 3537–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, R.M.; Worsley, A.; Timperio, A.; McNaughton, S.A. Understanding meal patterns: Definitions, methodology and impact on nutrient intake and diet quality. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2015, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltaouras, G.; Kyrkili, A.; Bathrellou, E.; Georgoulis, M.; Yannakoulia, M.; Bountziouka, V.; Smrke, U.; Dimitrakopoulos, G.; Kontogianni, M.D. Associations between Meal Patterns and Risk of Overweight/Obesity in Children and Adolescents in Western Countries: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies and Randomised Controlled Trials. Children 2024, 11, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Macdonald, I.A.; Taylor, M.A. A systematic review of associations between day-to-day variability in meal pattern and body weight, components of the metabolic syndrome and cognitive function. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 316–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Nutrition Foundation. Food and Your Brain. Available online: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutrition-for/food-and-the-brain/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Mou, Y.; Blok, E.; Barroso, M.; Jansen, P.W.; White, T.; Voortman, T. Dietary patterns, brain morphology and cognitive performance in children: Results from a prospective population-based study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 38, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, Y.A. Nutrition and Cognition in School-Aged Children: A Brief Review. Int. J. Educ. Benchmark 2016, 4, 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabane, S.; Chaabna, K.; Abraham, A.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the Middle East and North Africa: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Ramalhete, C.; Ferreira, I.; Bicho, M.; Valente, A. Sleep patterns, eating behavior and the risk of noncommunicable diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandner, M.A.; Hale, L.; Moore, M.; Patel, N.P. Mortality associated with short sleep duration: The evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Webb, T.L.; Martyn-St James, M.; Rowse, G.; Weich, S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 60, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines and Sustainability. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/dietary-guidelines/background/sustainable-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines: Implementation. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/dietary-guidelines/background/implementation/en/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Buckland, G.; Taylor, C.M.; Emmett, P.M.; Northstone, K. Prospective association between adherence to UK dietary guidelines in school-age children and cardiometabolic risk markers in adolescence/early adulthood in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 130, 1766–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaltiel, D.; Adjibade, M.; Deschamps, V.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Programme National Nutrition Santé–guidelines score 2 (PNNS-GS2): Development and validation of a diet quality score reflecting the 2017 French dietary guidelines. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thani, M.; Al Thani, A.A.; Al-Chetachi, W.; Al Malki, B.; Khalifa, S.A.; Bakri, A.H.; Hwalla, N.; Naja, F.; Nasreddine, L. Adherence to the Qatar dietary guidelines: A cross-sectional study of the gaps, determinants and association with cardiometabolic risk amongst adults. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawani, R.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Heskey, C.; Bahjri, K. Saudi Population’s Adherence to the Healthy Food Palm: A Cross-sectional Study. FASEB J. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, I.; Muhammad, A.N.S.; Murad, N.; Munir, M.K.; Khan, A.; Irshad, R.; Rahat, T.; Naz, S. Adherence to Pakistan dietary guidelines–Findings from major cities of Pakistan. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Conflict-Induced Acute Food Crises: Potential Policy Responses to Help Build Resilience; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Health and Well-Being Profile of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: An Overview of the Health Situation in the Region and Its Countries in 2019; World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: Cairo, Egypt, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Income Classification | Presence of National FBDGs |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Low-income | Yes |

| Bahrain | High-income | Yes |

| Djibouti | Lower middle-income | No |

| Egypt | Lower middle-income | No |

| Iran | Upper middle-income | Yes |

| Iraq | Upper middle-income | No |

| Jordan | Lower middle-income | Yes |

| Kuwait | High-income | Yes |

| Lebanon | Lower middle-income | Yes |

| Libya | Upper middle-income | No |

| Morocco | Lower middle-income | No |

| Oman | High-income | Yes |

| Pakistan | Lower middle-income | Yes |

| Palestine | Lower middle-income | Yes |

| Qatar | High-income | Yes |

| Saudi Arabia | High-income | Yes |

| Somalia | Low-income | No |

| Sudan | Low-income | No |

| Syrian Arab Republic | Low-income | No |

| Tunisia | Lower middle-income | No |

| UAE | High-income | Yes |

| Yemen | Low-income | No |

| Afghanistan [29] | Bahrain [30] | Iran [31] | Jordan [32] | Kuwait [33] | Lebanon [34] | Oman [35] | Pakistan [36] | Palestine [37] | Qatar [38] | Saudi Arabia [39] | UAE [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBDG title a | National food-based dietary guidelines for Afghans: A manual | The food national-based dietary guidelines for the Kingdom of Bahrain (Arabic: الإرشادات الغذائية البحرينية) | Food-based dietary guidelines for Iran (Persian: ایران رهنمودهای غذایی). | Food-based dietary guideline for Jordanians (Arabic: الدليل الارشادي الغذائي للأردنيين). | Kuwait food-based dietary guidelines (KFBDG) | The food-based dietary guideline manual for promoting healthy eating in the Lebanese adult population (Arabic: دليل الإرشادات التوجيهية الغذائية لتشجيع الغذاء السليم لدى البالغين اللبنانيين) | The Omani guide to healthy eating (Arabic: الدليل العماني للغذاء الصحي) | Pakistan dietary guidelines for better nutrition | Palestinian food-based dietary guidelines | Qatar dietary guidelines (Arabic: الدلائل الإرشادية للتغذية لدولة قطر). | Dietary guidelines for Saudis: The healthy food palm (Arabic: النخلة الغذائية الصحية) | United Arab Emirates Dietary guidelines (Arabic: الدليل الارشادي الوطني للتغذية |

| Year of publication b | 2016 | 2023 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | 2013 | 2023 | 2019 | 2021 | 2015 | 2012 | 2019 |

| If not the first version, year of previous publications | - | - | 2015 2006 1996 1993 1990 | - | - | - | 2009 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Years since last revision | Nine years | - | Ten years | Five years | - | Twelve years | - | Six years | Four years | Ten years | Thirteen years | Six years |

| Available language(s) | English | English and Arabic | Persian and English | Arabic | English | English and Arabic | English and Arabic | English | Arabic | English and Arabic | English | Arabic |

| FBDG purpose | ||||||||||||

| Healthy diet | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Disease prevention | - | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Pictorial illustration | Tablecloth | Not available | Pyramid | Olive tree (pyramid) | Food items and physical activity icons | Cedar (pyramid) | Food basket | Plate | Thobe (pyramid) | Seashell (plate) | Palm tree (pyramid) | Burj Khalifa |

| Afghanistan [29] | Bahrain [30] | Iran [31] | Jordan [32] | Kuwait [33] | Lebanon [34] | Oman [35] | Pakistan [36] | Palestine [37] | Qatar [38] | Saudi Arabia [39] | UAE [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | General population, which also includes infants and children; PW and LW | General population | General population over two years of age | General population, which also includes infants and children; Adolescents; PW and LW; Older adults | General population | Adult population | General population | General population, which also includes infants and children; Adolescents; PW and LW; Older adults | General population two years and above | General population | General population two years and above | General population two years and above |

| To be used by policymakers and/or HCPs and/or nutritionists and/or nutrition educators | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Special population groups addressed | - | Children and adolescents PW Older adults Vegetarians Lactose intolerant | - | Vegetarians Lactose intolerant | Children and adolescents WRA, PW, and LW Older adults Vegetarians Lactose intolerant Physically active individuals | WRA, PW, LW, and postmenopausal women Older adults Vegetarians Lactose intolerant Individuals with weakened immune systems | Children and adolescents WRA, PW, and LW Older adults Vegetarians Individuals with G6PD deficiency | - | WRA, PW, and LW Older adults Vegetarians Lactose intolerant Infants | LW Older adults Vegetarians Lactose-free consumers Infants | Children and adolescents PW and LW Older adults | - |

| Afghanistan [29] | Guideline 1. Eat different types of food daily Guideline 2. Eat different types of fruit and vegetables daily Guideline 3. Eat lean meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products Guideline 4. Reduce sugar intake and avoid sweet carbonated beverages Guideline 5. Use less salt, and eat fewer fatty foods and highly processed foods Guideline 6. Pregnant and lactating women should increase intake of all the food groups daily, especially foods that are rich in iron Guideline 7. Give infants only breast milk for the first six months of life Guideline 8. From six months onward, feed infants and young children different nutritious foods in addition to breast milk and continue breastfeeding until 24 months Guideline 9. Use clean and safe water for handwashing, drinking, and food preparation Guideline 10. If you live a sedentary life, do some physical activity for at least 20–30 min daily |

| Bahrain [30] | Guideline 1. Look after your body weight today to enhance your health tomorrow Guideline 2. Move more. Exercise not only optimizes your body, it enhances your mind and mood Guideline 3. Try varying and balancing your diet. This a lifestyle, not “all or nothing” Guideline 4. Keep it simple by sticking to more fruits and vegetables Guideline 5. Switch to healthier animal proteins, while emphasizing low-fat milk and dairy and fish/sea food Guideline 6. Choose vegetarian alternatives to red and processed meat such as legumes and unsalted nuts Guideline 7. Pay attention to your intake of salt and sugar, especially the hidden ones Guideline 8. Stay hydrated with water and healthy fluids Guideline 9. Observe the recommendations for safe food production and consumption Guideline 10. Contribute to protecting the environment, feeding the hungry, and saving money by decreasing food waste Guideline 11. Eat homemade foods with others to promote enjoyment and connect with cultural heritage |

| Jordan [32] | Guideline 1. Maintain a healthy body weight Guideline 2. Be physically active every day Guideline 3. Drink enough safe water every day and make it your first choice Guideline 4. Follow a healthy and nutritious dietary pattern with the five food groups Guideline 5. Eat adequate amounts of seasonal vegetables and fruits daily Guideline 6. Eat different kinds of whole grains Guideline 7. Consume legumes daily and enjoy some unsalted nuts and seeds Guideline 8. Consume sufficient amounts of milk and dairy products daily Guideline 9. Consume lean red meats, fish, and poultry Guideline 10. Avoid consuming fats in large quantities Guideline 11. Limit the intake of foods and beverages high in sugar, especially added sugar Guideline 12. Limit the intake of table salt and high-salt foods Guideline 13. Read the nutrition labels when purchasing food products Guideline 14. Follow food safety guidelines when preparing, consuming, and storing food Guideline 15. Ensure daily adequate sleep and rest and maintain a healthy lifestyle Guideline 16. Obtain nutritional information from specialized sources |

| Kuwait [33] | Guideline 1. Eat a healthy and balanced diet consisting of the five food groups every day Guideline 2. Make natural and minimally processed foods the base of your daily meals Guideline 3. Drink adequate amount of water every day Guideline 4. Limit your intake of fat, added sugar, and salt Guideline 5. Know your food: Read the food labels to make healthier choices Guideline 6. Practice safe and clean food handling methods Guideline 7. Adopt a healthy lifestyle and protect your environment Guideline 8. Maintain a healthy body weight Guideline 9. Move more and stay active |

| Lebanon [34] | Guideline 1. Enjoy and maintain a healthy body weight Guideline 2. Be physically active every day Guideline 3. Eat a variety of nutritious foods every day for a balanced diet Guideline 4. Eat cereals, especially whole grains, as a basis of daily meals Guideline 5. Enjoy more fruit and vegetables daily Guideline 6. Consume legume-based dishes regularly and enjoy some unsalted nuts and seeds Guideline 7. Consume low-fat milk and dairy products every day Guideline 8. Consume at least two servings of fish, including fatty fish, every week Guideline 9. Consume lean red meat and poultry Guideline 10. Limit intake of sugar, especially added sugar from sweetened foods and beverages Guideline 11. Limit intake of solid fats and replace with vegetable oils Guideline 12. Limit intake of table salt and high-salt foods Guideline 13. Drink plenty of safe water every day Guideline 14. Eat safe food |

| Oman [35] | Guideline 1. Maintain a healthy body weight for better health and well-being Guideline 2. Be active and exercise Guideline 3. Vary your diet: variety is the spice of life Guideline 4. Know your portion size Guideline 5. Eat more vegetables and fruits every day Guideline 6. Choose whole grains Guideline 7. Eat legumes, and add unsalted nuts and seeds to your diet Guideline 8. Eat more fish, less red meat, and avoid processed meat Guideline 9. Choose low-fat, unsweetened dairy products Guideline 10. Switch to healthier fats and oils Guideline 11. Choose food with less salt Guideline 12. Hold back on sugar Guideline 13. Drink plenty of safe water and eat safe food |

| Pakistan [36] | Guideline 1. Maintain normal body weight by consuming all food groups and performing regular physical activity Guideline 2. Half of your daily cereals intake should include whole grains Guideline 3. Eat five servings of fresh vegetables and fruits a day Guideline 4. Take two to three servings of milk and milk products in a day Guideline 5. Consume meat and meat products, fish, and eggs in moderation Guideline 6. Encourage consumption of pulses to attain healthy growth Guideline 7. Consume fortified flour, grains, and their products Guideline 8. Limit consumption of edible oil and fat in cooking Guideline 9. Reduce sugar intake, and limit intake of soft drinks, confectionaries, bakery products, and commercial fruit drinks Guideline 10. Limit salt in cooking and always use iodized salt Guideline 11. Limit consumption of fatty foods and highly processed foods Guideline 12. Change sedentary lifestyle to physically active lifestyle Guideline 13. Exclusively breastfeed the baby in the first six months and continue breastfeeding along with complementary feeding at least for two years Guideline 14. Women should increase intake of all the food groups daily, especially foods that are rich in iron, and take extra care during pregnancy and lactation Guideline 15. Drink plenty of water each day Guideline 16. Read nutrition labeling on packaged food products |

| Palestine [37] | Guideline 1. Maintain an ideal body weight Guideline 2. Drink sufficient quantities of clean water Guideline 3. Follow a healthy and balanced dietary pattern that includes all food groups Guideline 4. Eat adequate amounts of vegetables and fruits daily Guideline 5. Eat all kinds of whole grains Guideline 6. Consume legumes daily and enjoy some unsalted nuts and seeds in moderation Guideline 7. Consume sufficient amounts of milk and dairy products daily Guideline 8. Consume a variety of lean red meats, fish, and poultry Guideline 9. Avoid consuming fats and oils in large quantities Guideline 10. Limit the intake of foods and beverages high in sugar, especially added sugar Guideline 11. Limit the intake of table salt and high-salt foods Guideline 12. Read the nutrition labels when purchasing food products Guideline 13. General food safety guidelines when preparing, consuming, and storing food Guideline 14. Ensure daily adequate sleep and rest Guideline 15. Obtain food and nutritional information from specialized sources |

| Qatar [38] | Guideline 1. Eat a variety of healthy choices from the 6 food groups Guideline 2. Maintain a healthy weight Guideline 3. Limit sugar, salt, and fat Guideline 4. Be physically active Guideline 5. Drink plenty of water Guideline 6. Adopt safe and clean food preparation methods Guideline 7. Eat healthy while protecting the environment Guideline 8. Take care of your family |

| Saudi Arabia [39] | Guideline 1. Enjoy a variety of food items from major food groups daily Guideline 2. Choose whole grains Guideline 3. Consume a variety of fruits and vegetables Guideline 4. Limit the intake of foods with a high content of saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, salt, and sugar Guideline 5. Achieve and maintain a healthy body weight Guideline 6. Drink water Guideline 7. Purchase, prepare, cook, and store food in ways to ensure food safety Guideline 8. Be physically active |

| UAE [40] | Guideline 1. Support and emphasize a healthy lifestyle through a healthy diet and physical activity for all Guideline 2. Maintain the consumption of healthy foods throughout the different stages of life Guideline 3. Reduce calories by lowering sugar and fat, especially saturated and trans fats, and lowering salt intake Guideline 4. Consume a variety of nutritious and energy dense foods and beverages Guideline 5. To adopt healthy dietary patterns, replace unhealthy foods with healthy foods Guideline 6. Food safety |

| Afghanistan [29] | Bahrain [30] | Iran [31] | Jordan [32] | Kuwait [33] | Lebanon [34] | Oman [35] | Pakistan [36] | Palestine [37] | Qatar [38] | Saudi Arabia [39] | UAE [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy body weight | - | Look after your body weight today to enhance your health tomorrow. | Eat in amounts so that your ideal body weight will be maintained. | Maintain your healthy weight. | Maintain a healthy body weight. | Enjoy and maintain a healthy body weight. | Maintain a healthy body weight for better health and well-being. | Maintain normal body weight by consuming all food groups and performing regular physical activity. | Maintain an ideal weight. | Maintain a healthy weight. | Achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. | - |

| Varied and balanced diet | Eat different types of foods daily. | Try varying and balancing your diet. This a lifestyle, not “all or nothing”. | Select a balanced, varied diet. | Follow a healthy and varied diet from the five food groups. | Eat a healthy and balanced diet consisting of the five food groups every day. | Eat a variety of nutritious foods every day for a balanced diet. | Vary your diet: variety is the spice of life. | Maintain normal body weight by consuming all food groups and performing regular physical activity. | Follow a healthy and balanced diet that includes all food groups. | Eat a variety of healthy choices from the six food groups. | Enjoy a variety of food items from major food groups daily. | Diversify the intake of nutrient-dense and high-density foods and beverage. |

| The importance of meal patterns | - | Special population children and adolescents: Help your children develop healthy eating behaviors and dietary patterns. Eating in isolation is linked to many unhealthy dietary patterns such as stress eating and binge eating. | - | For underweight: Eat multiple and separate meals so that there are three snacks in addition to three main meals. | - | For underweight: Eat small and frequent meals throughout the day. | Maintain a healthy eating pattern, with three main meals (and two snacks). | - | - | Build and model healthy patterns for your family. Adopting healthy eating and activity patterns that can be maintained over time is a more effective way to lose weight than dieting. | - | - |

| Physical activity | If you live a sedentary life, do some physical activity for at least 20–30 min daily. Adults: At least 30 min of moderate to vigorous activity most days of the week. | Move more. Exercise not only optimizes your body, it enhances your mind and mood. Adults: At least 150 to 300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity OR At least 75 to 150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity OR Equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. | Try to exercise regularly, at least three days per week, 30–40 min each time. | Be physically active daily. Adults: Engage in moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 30 min a day. | Move more and stay active. Adults: At least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. | Be physically active every day. Adults: At least 30 min of moderate-intensity physical activity five days per week. | Be active and exercise. Adults: At least 30 min of daily moderate-intensity physical activity five days per week. or 20 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity three days per week. | Change sedentary lifestyle to physically active lifestyle. Adults: At least 30 min or more moderate exercise. | Be physically active daily. Adults: At least 30 min daily, five days per week. | Be physically active. Adults: Moderate intensity at least five days per week (for at least 30 min) and/or vigorous-intensity aerobic at least three days per week (for at least 20 min). | Be physically active. Adults: Intermittent walking for 15 to 30 min, 3–4 times/week; and subsequently increase in physical activity for 30–60 min on most if not all days of the week. | Supporting and promoting a healthy lifestyle through healthy food and physical activity for all. Adults: At least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity OR At least 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity OR Equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. |

| Sleep | - | Tips for achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight among children and adolescents; ensuring adequate sleep, | - | Get enough sleep and rest daily and maintain a healthy lifestyle. | Adopt a healthy lifestyle and protect your environment: Healthy sleeping habits | - | - | - | Get enough sleep and rest daily. | For weight loss: Getting enough sleep is essential. Recent research suggests that a lack of sleep is related to overweight and obesity. Getting enough sleep may also help you to have enough energy to exercise. | - | Adequate number of sleep hours per age group. |

| Emotional well-being/mindfulness | - | Eat homemade foods with others to promote enjoyment and connect with cultural heritage. | - | - | Avoid distractions during mealtimes and focus on being more mindful while eating. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Afghanistan [29] | Bahrain [30] | Iran [31] | Jordan [32] | Kuwait [33] | Lebanon [34] | Oman [35] | Pakistan [36] | Palestine [37] | Qatar [38] | Saudi Arabia [39] | UAE [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food and water safety | ||||||||||||

| Food safety handling practices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Clean water use and consumption | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | - | - | - |

| Environmental factors | - | √ | - | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Sustainability | - | √ | - | - | - | - | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Food waste | - | √ | - | - | √ | - | √ | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Cost and affordability | - | √ | - | - | - | √ | - | √ | - | - | - | - |

| Food labeling | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 World Health Organization. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In any reproduction of this article there should not be any suggestion that WHO or this article endorse any specific organisation or products. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article’s original URL.

Share and Cite

Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Taktouk, M.; Fahd, R.; Ayoub, J.; Nasreddine, L. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison and an Update. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121790

Al-Jawaldeh A, Taktouk M, Fahd R, Ayoub J, Nasreddine L. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison and an Update. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121790

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Jawaldeh, Ayoub, Mandy Taktouk, Rhea Fahd, Jennifer Ayoub, and Lara Nasreddine. 2025. "Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison and an Update" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121790

APA StyleAl-Jawaldeh, A., Taktouk, M., Fahd, R., Ayoub, J., & Nasreddine, L. (2025). Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison and an Update. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121790